Singapore: Transitioning to a "New Normal" in a Post-Lee Kuan Yew Era Eugene K

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Why Are Gender Reforms Adopted in Singapore? Party Pragmatism and Electoral Incentives* Netina Tan

Why Are Gender Reforms Adopted in Singapore? Party Pragmatism and Electoral Incentives* Netina Tan Abstract In Singapore, the percentage of elected female politicians rose from 3.8 percent in 1984 to 22.5 percent after the 2015 general election. After years of exclusion, why were gender reforms adopted and how did they lead to more women in political office? Unlike South Korea and Taiwan, this paper shows that in Singapore party pragmatism rather than international diffusion of gender equality norms, feminist lobbying, or rival party pressures drove gender reforms. It is argued that the ruling People’s Action Party’s (PAP) strategic and electoral calculations to maintain hegemonic rule drove its policy u-turn to nominate an average of about 17.6 percent female candidates in the last three elections. Similar to the PAP’s bid to capture women voters in the 1959 elections, it had to alter its patriarchal, conservative image to appeal to the younger, progressive electorate in the 2000s. Additionally, Singapore’s electoral system that includes multi-member constituencies based on plurality party bloc vote rule also makes it easier to include women and diversify the party slate. But despite the strategic and electoral incentives, a gender gap remains. Drawing from a range of public opinion data, this paper explains why traditional gender stereotypes, biased social norms, and unequal family responsibilities may hold women back from full political participation. Keywords: gender reforms, party pragmatism, plurality party bloc vote, multi-member constituencies, ethnic quotas, PAP, Singapore DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5509/2016892369 ____________________ Netina Tan is an assistant professor of political science at McMaster University. -

2Nd REPLY by MS GRACE FU, SENIOR MINISTER of STATE for NATIONAL DEVELOPMENT and EDUCATION, on DELIVERING a STUDENT- CENTRIC EDUCATION

FY 2011 COMMITTEE OF SUPPLY DEBATE: 2nd REPLY BY MS GRACE FU, SENIOR MINISTER OF STATE FOR NATIONAL DEVELOPMENT AND EDUCATION, ON DELIVERING A STUDENT- CENTRIC EDUCATION 1. Sir, allow me to address specific issues raised by members, and elaborate on two key areas: (i) First, our efforts to create a student-centric learning environment; and; (iii) Second, providing more support for students with special needs. (I) SUBSTANTIVE AND INNOVATIVE INVESTMENTS TO DELIVER A STUDENT- CENTRIC EDUCATION Enhanced School Infrastructure to Support Holistic Education 2. Mrs Josephine Teo and Mdm Halimah Yacob asked for an update on the Primary Education Review and Implementation Committee’s (or PERI) recommendations. We are upgrading 40 more Primary schools in Phase 3. This will facilitate primary schools to transit to single session and allow strengthening of non- academic aspects of education like PE, Art and Music. 3. These upgraded schools will have newer and better facilities to support more innovative and engaging lessons. Allow me to cite a few examples. 4. The first slide shows a PE lesson at Hougang Primary School. To support a more holistic education, indoor sports halls such as this will allow PE lessons and CCAs to be conducted throughout the day, rain or shine. All schools that need it will be equipped with synthetic turf, which is cheaper to maintain and can be used immediately after it rains. 5. For the Performing and Visual Arts, schools will have band rooms, dance studios, and performing arts studios. Here we see a Performing Arts Studio at Lianhua Primary, which is integrated into the library to maximise the use of space. -

ASA 36/07/94 Distr: UA/SC UA 256/94

EXTERNAL (for general distribution) AI Index: ASA 36/07/94 Distr: UA/SC UA 256/94 Death Penalty 4 July 1994 SINGAPORE Jasbir SINGH, aged 30 Charanjit SINGH, age not known On 14 February 1994 the Court of Criminal Appeal rejected the appeal of Jasbir Singh and Charanjit Singh against their sentence of death for trafficking in 254.36 grams of diamorphine. Jasbir and Charanjit were arrested on 24 May 1988 on charges of drug trafficking. Jasbir had been staying at the flat of an acquaintance who was away on holiday. There he found a bag of powder and was arrested while trying to determine the nature of this powder. Jasbir had asked his friend Charanjit to accompany him. Both were tried and sentenced to death on 5 January 1993. They will now file an appeal for clemency with the President of Singapore, Ong Teng Cheong. BACKGROUND INFORMATION The death penalty was employed during the colonial period and was retained after Singapore became an independent republic in August 1965. Anyone found in possession of more than 15 grams of heroin, 30 grams of morphine, 30 grams of cocaine or 500 grams of cannabis is presumed guilty of drug trafficking and is liable to a mandatory death sentence. Amnesty International opposes the death penalty in all cases as a violation of the right to life and the right not to be subjected to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment, as proclaimed in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. RECOMMENDED ACTION: Please send telegrams/telexes/faxes/express and airmail letters either in English or in your own language: - expressing concern at the imposition of the death sentence on Jasbir Singh and Charanjit Singh; - stating Amnesty International's unconditional opposition to the death penalty. -

Full Version of Cv

Adrian David Cheok AM Phone: +61423977539 or +60128791271 19A Robe Terrace Email: [email protected] Medindie, 5081 Homepage: https://www.adriancheok.info Australia https://www.imagineeringinstitute.org Personal Date of Birth: December 18, 1971. Place of birth: Adelaide, Australia Australian Citizen. Summary of Career Adrian David Cheok AM is Director of the Imagineering Institute, Malaysia, Full Professor at i-University Tokyo, Visiting Professor at Raffles University, Malaysia, Visiting Professor at University of Novi Sad-Serbia, on Technical faculty \Mihailo Pupin", Serbia, Faculty of Ducere Business School, and CEO of Nikola Tesla Technologies Corporation. He is Founder and Director of the Mixed Reality Lab, Singapore. He was formerly Professor of Pervasive Computing, University of London, Full Professor and Executive Dean at Keio University, Graduate School of Media Design and Associate Professor in the National University of Singapore. He has previously worked in real-time systems, soft computing, and embedded computing in Mitsubishi Electric Research Labs, Japan. In 2019, The Governor General of Australia, Representative of Her Majesty the Queen Elizabeth II, has awarded Australia's highest honour the Order of Australia to Adrian David Cheok for his contribution to international education and research. He has been working on research covering mixed reality, human-computer interfaces, wearable computers and ubiquitous computing, fuzzy systems, embedded systems, power electronics. He has successfully obtained approximately $130 million dollars in funding for externally funded projects in the area of wearable computers and mixed reality from Daiwa Foundation, Khazanah National (Malaysian Government), Media Development Authority, Nike, National Oilwell Varco, Defence Science Technology Agency, Ministry of Defence, Ministry of Communications and Arts, National Arts Council, Singapore Sci- ence Center, and Hougang Primary School. -

SC 100Yrs DG Speech Final (080110)

WELCOME ADDRESS BY DIRECTOR-GENERAL OF CUSTOMS MR FONG YONG KIAN AT SINGAPORE CUSTOMS’ CENTENNIAL CELEBRATIONS, 8 JANUARY 2010, 11.10 AM, ORCHID COUNTRY CLUB Prime Minister, Mr Lee Hsien Loong Minister for Finance, Mr Tharman Shanmugaratnam Minister, Prime Minister’s Office and Second Minister for Finance and Transport, Mrs Lim Hwee Hua Distinguished Guests Fellow Colleagues INTRODUCTION 1. A very warm welcome to all of you. I would like to thank Prime Minister Lee for gracing this joyous event and our distinguished guests for joining us in commemorating this historic occasion for Singapore Customs. It is our pleasure and honour to have all of you here with us. 2. Today, we celebrate 100 years of Singapore Customs. The past 100 years contained many exciting changes for Customs. If one were to listen to different generations of Customs officers recounting their careers, we would no doubt hear many diverse stories. Customs’ roles have indeed evolved over the century. Please allow me to give a brief account of our history. 1 OUR HISTORY – RESPONDING TO TIMES 3. We trace our roots back to 1 st Jan 1910, when the Government Monopolies Department was formed under the Government of Straits Settlement to regulate and collect revenue from opium and liquor. At that time, these provided the colonial government with a steady and key source of income. 4. Tariff was later extended to tobacco and the Department also took over the collection of duty on petroleum from the Treasury. As the government increased its reliance on revenue from duties on tobacco, petroleum and liquor, the Government Monopolies Department was renamed as Excise Department in 1935, and later in 1938 to Department of Customs and Excise. -

Our Journey Has Just Begun

Temasek Review 2014 Review Temasek Our journey has just begun Temasek Review 2014 Our journey has just begun Cover: Sherlyn Lim on an outing with her sons, Amos and Dean, on Sentosa Island, Singapore. Our journey has just begun The world is fast changing around us. Populations urbanise, and life expectancies continue to rise. We are entering a new digital age – machines are increasingly smarter, and people ever more connected. Change brings unprecedented challenges – competing demands for finite resources, safe food and clean water; health care for an ageing population. Challenges spawn novel solutions – personalised medicine, digital currencies, and more. As investor, institution and steward, Temasek is ready to embrace the future with all that it brings. With each step, we forge a new path. At 40, our journey has just begun. TR2014_version_28 12.00pm 26 June 2014 Contents The Temasek Charter 4 Ten-year Performance Overview 6 Portfolio Highlights 8 From Our Chairman 10 Investor 16 Value since Inception 18 Total Shareholder Return 19 Investment Philosophy 20 Year in Review 24 Looking Ahead 26 Managing Risk 28 Institution 34 Our MERITT Values 36 Public Markers 37 Our Temasek Heartbeat 38 Financing Framework 42 Wealth Added 44 Remuneration Philosophy 45 Seeding Future Enterprises 48 Board of Directors 50 Senior Management 57 2 Temasek Review 2014 Contents Steward 60 Trusted Steward 62 Fostering Stewardship and Governance 67 Social Endowments & Community Engagement 68 Touching Lives 72 From Ideas to Solutions 74 Engaging Friends 75 Temasek International Panel 76 Temasek Advisory Panel 77 Group Financial Summary 78 Statement by Auditors 80 Statement by Directors 81 Group Financial Highlights 82 Group Income Statements 84 Group Balance Sheets 85 Group Cash Flow Statements 86 Group Statements of Changes in Equity 87 Major Investments 88 Contact Information 98 Temasek Portfolio at Inception 100 Explore Temasek Review 2014 at www.temasekreview.com.sg or scan the QR code 3 TR2014_version_28 12.00pm 26 June 2014 A journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step. -

1 Singapore's Dominant Party System

Tan, Kenneth Paul (2017) “Singapore’s Dominant Party System”, in Governing Global-City Singapore: Legacies and Futures after Lee Kuan Yew, Routledge 1 Singapore’s dominant party system On the night of 11 September 2015, pundits, journalists, political bloggers, aca- demics, and others in Singapore’s chattering classes watched in long- drawn amazement as the media reported excitedly on the results of independent Singa- pore’s twelfth parliamentary elections that trickled in until the very early hours of the morning. It became increasingly clear as the night wore on, and any optimism for change wore off, that the ruling People’s Action Party (PAP) had swept the votes in something of a landslide victory that would have puzzled even the PAP itself (Zakir, 2015). In the 2015 general elections (GE2015), the incumbent party won 69.9 per cent of the total votes (see Table 1.1). The Workers’ Party (WP), the leading opposition party that had five elected members in the previous parliament, lost their Punggol East seat in 2015 with 48.2 per cent of the votes cast in that single- member constituency (SMC). With 51 per cent of the votes, the WP was able to hold on to Aljunied, a five-member group representation constituency (GRC), by a very slim margin of less than 2 per cent. It was also able to hold on to Hougang SMC with a more convincing win of 57.7 per cent. However, it was undoubtedly a hard defeat for the opposition. The strong performance by the PAP bucked the trend observed since GE2001, when it had won 75.3 per cent of the total votes, the highest percent- age since independence. -

Xerox University Microfilms 300 North Zeeb Road Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or “target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “ Missing Page(s)“ . If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in “sectioning" the material. It is customary tc begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from “ photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

Annex B (Pdf, 314.38KB)

ANNEX B CABINET AND OTHER OFFICE HOLDERS (1 May 2014 unless stated otherwise) MINISTRY MINISTER MINISTER OF STATE PARLIAMENTARY SECRETARIES PMO Prime Minister's Office Mr Lee Hsien Loong Mr Heng Chee How (Prime Minister) (Senior Minister of State) Mr Teo Chee Hean #@ Mr Sam Tan ^*# (Deputy Prime Minister and (Minister of State) Coordinating Minister for National Security and Minister for Home Affairs) Mr Tharman Shanmugaratnam #@ (Deputy Prime Minister and Minister for Finance) Mr Lim Swee Say @ Mr S Iswaran # (Minister, PMO, Second Minister for Home Affairs and Second Minister for Trade and Industry) Ms Grace Fu Hai Yien #@ (Minister, PMO, Second Minister for Environment and Water Resources and Second Minister for Foreign Affairs) FOREIGN AFFAIRS, SECURITY AND DEFENCE Defence Dr Ng Eng Hen Dr Mohamad Maliki Bin Osman # (Minister of State) Mr Chan Chun Sing # (Second Minister) Foreign Affairs Mr K Shanmugam # Mr Masagos Zulkifli # (Senior Minister of State) Ms Grace Fu Hai Yien #@ (Second Minister) Home Affairs Mr Teo Chee Hean #@ Mr Masagos Zulkifli # (Deputy Prime Minister) (Senior Minister of State) Mr S Iswaran # (Second Minister) Law Mr K Shanmugam # Ms Indranee Rajah # (Senior Minister of State) ECONOMICS Trade and Industry Mr Lim Hng Kiang Mr Lee Yi Shyan # (Senior Minister of State) Mr S Iswaran #+ Mr Teo Ser Luck # (Second Minister) (Minister of State) Finance Mr Tharman Shanmugaratnam #@ Mrs Josephine Teo # (Deputy Prime Minister) (Senior Minister of State) Transport Mr Lui Tuck Yew Mrs Josephine Teo # A/P Muhammad Faishal bin -

Votes and Proceedings of the Twelfth Parliament of Singapore

VOTES AND PROCEEDINGS OF THE TWELFTH PARLIAMENT OF SINGAPORE First Session MONDAY, 13 MAY 2013 No. 54 1.30 pm 386 PRESENT: Mdm SPEAKER (Mdm HALIMAH YACOB (Jurong)). Mr ANG WEI NENG (Jurong). Mr BAEY YAM KENG (Tampines). Mr CHAN CHUN SING (Tanjong Pagar), Acting Minister for Social and Family Development and Senior Minister of State, Ministry of Defence. Mr CHEN SHOW MAO (Aljunied). Dr CHIA SHI-LU (Tanjong Pagar). Mrs LINA CHIAM (Non-Constituency Member). Mr CHARLES CHONG (Joo Chiat), Deputy Speaker. Mr CHRISTOPHER DE SOUZA (Holland-Bukit Timah). Ms FAIZAH JAMAL (Nominated Member). Mr NICHOLAS FANG (Nominated Member). Mr ARTHUR FONG (West Coast). Mr CEDRIC FOO CHEE KENG (Pioneer). Ms FOO MEE HAR (West Coast). Ms GRACE FU HAI YIEN (Yuhua), Minister, Prime Minister's Office, Second Minister for the Environment and Water Resources and Second Minister for Foreign Affairs. Mr GAN KIM YONG (Chua Chu Kang), Minister for Health and Government Whip. Mr GAN THIAM POH (Pasir Ris-Punggol). Mr GERALD GIAM YEAN SONG (Non-Constituency Member). Mr GOH CHOK TONG (Marine Parade). No. 54 13 MAY 2013 387 Mr HAWAZI DAIPI (Sembawang), Senior Parliamentary Secretary to the Minister for Education and Acting Minister for Manpower. Mr HENG CHEE HOW (Whampoa), Senior Minister of State, Prime Minister's Office and Deputy Leader of the House. Mr HRI KUMAR NAIR (Bishan-Toa Payoh). Ms INDRANEE RAJAH (Tanjong Pagar), Senior Minister of State, Ministry of Law and Ministry of Education. Dr INTAN AZURA MOKHTAR (Ang Mo Kio). Mr S ISWARAN (West Coast), Minister, Prime Minister's Office, Second Minister for Home Affairs and Second Minister for Trade and Industry. -

Islam in a Secular State Walid Jumblatt Abdullah Islam in a Secular State

RELIGION AND SOCIETY IN ASIA Abdullah Islam in a Secular State a Secular in Islam Walid Jumblatt Abdullah Islam in a Secular State Muslim Activism in Singapore Islam in a Secular State Religion and Society in Asia This series contributes cutting-edge and cross-disciplinary academic research on various forms and levels of engagement between religion and society that have developed in the regions of South Asia, East Asia, and South East Asia, in the modern period, that is, from the early 19th century until the present. The publications in this series should reflect studies of both religion in society and society in religion. This opens up a discursive horizon for a wide range of themes and phenomena: the politics of local, national and transnational religion; tension between private conviction and the institutional structures of religion; economical dimensions of religion as well as religious motives in business endeavours; issues of religion, law and legality; gender relations in religious thought and practice; representation of religion in popular culture, including the mediatisation of religion; the spatialisation and temporalisation of religion; religion, secularity, and secularism; colonial and post-colonial construction of religious identities; the politics of ritual; the sociological study of religion and the arts. Engaging these themes will involve explorations of the concepts of modernity and modernisation as well as analyses of how local traditions have been reshaped on the basis of both rejecting and accepting Western religious, -

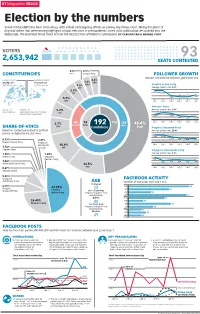

200708 BT Ge2020 in Numbers

BT Infographics GE2020 Election by the numbers Social media platforms have been abuzz with virtual campaigning efforts as polling day draws close, taking the place of physical rallies that were among highlights of past elections in pre-pandemic times. With political parties pushed into the digital age, The Business Times looks at how the GE2020 has unfolded in cyberspace. BY CLAUDIA TAN & NATALIE CHOY VOTERS 93 2,653,942 SEATS CONTESTED 0.5% 0.5% CONSTITUENCIES PPP Independent FOLLOWER GROWTH Number of Facebook followers gained per day Largest GRC Smallest SMC 2.6% Ang Mo Kio Potong Pasir 2.6% SDA 185,465 electors 19,740 electors 2.6% RDU People’s Action Party SPP Average growth rate: 2.3% 3.1% 1,332 RP 1,347 338 338 653 5.2% 516 NSP July 1 July 2 July 3 July 4 July 5 July 6 Workers’ Party GRCs: 17 SMCs: 14 5.2% Average growth rate: 9.5% New: Sengkang New: Kebun Baru, Yio Chu Kang, PV Marymount, Punggol West 2,699 2,098 2,421 1,474 1,271 1,336 July 1 July 2 July 3 July 4 July 5 July 6 5.7% 40 74 118 152 48.4% Female New 192PSP Male SHARE-OF-VOICE SDP Candidates PAP Progress Singapore Party Based on content generated by political Average growth rate: 22.4% parties on digital media platforms 1,539 1,539 1,119 0.19% 2.29% 932 836 776 People’s Power Party Singapore Democratic 10.9% July 1 July 2 July 3 July 4 July 5 July 6 1.72% Alliance WP Peoples Voice Singapore Democratic Party 1.48% 1.60% Average growth rate: 5.6% Reform Party Singapore People’s Party 813 1.46% 498 558 565 503 540 National Solidarity Party 12.5% 0.67% PSP July 1 July 2