Texas in the Civil War

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Govenor Miriam A. Ferguson

East Texas Historical Journal Volume 17 Issue 2 Article 5 10-1979 Govenor Miriam A. Ferguson Ralph W. Steen Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ethj Part of the United States History Commons Tell us how this article helped you. Recommended Citation Steen, Ralph W. (1979) "Govenor Miriam A. Ferguson," East Texas Historical Journal: Vol. 17 : Iss. 2 , Article 5. Available at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ethj/vol17/iss2/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the History at SFA ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in East Texas Historical Journal by an authorized editor of SFA ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EAST TEXAS HISTORICAL ASSOCIAnON 3 GOVERNOR MIRIAM A. FERGUSON by Ralph W. Steen January 20, 1925 was a beautiful day in Austin, Texas, and thousands of people converged on the city to pay tribute to the first woman to serve the state as governor. Long before time for the inaugural ceremony to begin every space in the gallery of the House of Representatives was taken and thousands who could not gain admission blocked hanways and stood outside the capitol. After brief opening ceremonies, Chief Justice C.M. Cureton administered the oath of office to Lieutenant Governor Barry Miller and then to Governor Miriam A. Ferguson. Pat M. Neff, the retiring governor, introduced Mrs. Ferguson to the audience and she delivered a brief inaugural address. The governor called for heart in government, proclaimed political equality for women, and asked for the good will and the prayers of the women of Texas. -

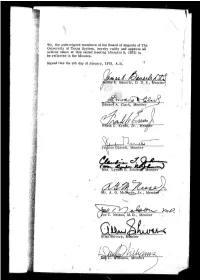

Board Minutes for January 9, 1973

1 ~6 ]. J We, the uudersigaed members of the Board of Regeats of The Uaiversity of Texas System, hereby ratify aad approve all z actions takea at this called meetiag (Jauuary 9, 1973) to be reflected in the Minutes. Signed this the 9Lh day of Jaauary, -1973, A.D. ol Je~ins Garrett, Member c • D., Member Allan( 'Shivers, M~mber ! ' /" ~ ° / ~r L ,.J J ,© Called Meeting Meeting No. 710 THE MINUTES OF THE BOARD OF REGENTS OF THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS SYSTEM Pages I and 2 O January ~, 1973 '~ Austin, Texas J~ 1511 ' 1-09-7) ~ETING NO. 710 TUESDAY, JANUARY 9, 1973.--Pursuant to the call of the Chair on January 6, 1973 (and which call appears in the Minutes of the meeting of that date), the Board of Regents convened in a Called Session at i:00 p.m~ on January 9, 1973, in the Library of the Joe C. Thompson Conference Center, The Uni- versity of Texas at Austin, Austin, Texas, with the follow- ing in attendance: ,t ATTENDANCE.-- Present Absent Regent James E. Baue-~ None Regent Edward Clark Regent Frank C. Erwin, Jr. "#~?::{ill Regent Jenkins Garrett Regent (Mrs.) Lyndon Johnson Regent A. G. McNeese, Jr. );a)~ Regent Joe T. Nelson Regent Allan Shivers Regent Dan C. Williams Secretary Thedford Chancellor LeMaistre Chancellor Emeritus Ransom Deputy Chancellor Walker (On January 5, 1973, Governor Preston Smith f~amed ~the < following members of the Board of Regents of The University of Texas System: ,~ ¢.Q .n., k~f The Honorable James E. Bauerle, a dentist of San Antonio, to succeed the Honorable John Peace of San Antonio, whose term had expired. -

Texas Office of Lt. Governor Data Sheet As of August 25, 2016

Texas Office of Lt. Governor Data Sheet As of August 25, 2016 History of Office The Office of the Lt. Governor of Texas was created by the State Constitution of 1845 and the office holder is President of the Texas Senate.1 Origins of the Office The Office of the Lt. Governor of Texas was established with statehood and the Constitution of 1845. Qualifications for Office The Council of State Governments (CSG) publishes the Book of the States (BOS) 2015. In chapter 4, Table 4.13 lists the Qualifications and Terms of Office for lieutenant governors: The Book of the States 2015 (CSG) at www.csg.org. Method of Election The National Lieutenant Governors Association (NLGA) maintains a list of the methods of electing gubernatorial successors at: http://www.nlga.us/lt-governors/office-of-lieutenant- governor/methods-of-election/. Duties and Powers A lieutenant governor may derive responsibilities one of four ways: from the Constitution, from the Legislature through statute, from the governor (thru gubernatorial appointment or executive order), thru personal initiative in office, and/or a combination of these. The principal and shared constitutional responsibility of every gubernatorial successor is to be the first official in the line of succession to the governor’s office. Succession to Office of Governor In 1853, Governor Peter Hansborough Bell resigned to take a seat in the U.S. House of Representatives and Lt. Governor James W. Henderson finished the unexpired term.2 In 1861, Governor Sam Houston was removed from office and Lt. Governor Edward Clark finished the unexpired term. In 1865, Governor Pendleton Murrah left office and Lt. -

2020-2022 Law School Catalog

The University of at Austin Law School Catalog 2020-2022 Table of Contents Examinations ..................................................................................... 11 Grades and Minimum Performance Standards ............................... 11 Introduction ................................................................................................ 2 Registration on the Pass/Fail Basis ......................................... 11 Board of Regents ................................................................................ 2 Minimum Performance Standards ............................................ 11 Officers of the Administration ............................................................ 2 Honors ............................................................................................... 12 General Information ................................................................................... 3 Graduation ......................................................................................... 12 Mission of the School of Law ............................................................ 3 Degrees ..................................................................................................... 14 Statement on Equal Educational Opportunity ................................... 3 Doctor of Jurisprudence ................................................................... 14 Facilities .............................................................................................. 3 Curriculum ................................................................................. -

Texas, Wartime Morale, and Confederate Nationalism, 1860-1865

“VICTORY IS OUR ONLY ROAD TO PEACE”: TEXAS, WARTIME MORALE, AND CONFEDERATE NATIONALISM, 1860-1865 Andrew F. Lang, B. A. Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2008 APPROVED: Richard G. Lowe, Major Professor Randolph B. Campbell, Committee Member Richard B. McCaslin, Committee Member Adrian R. Lewis, Chair of the Department of History Sandra L. Terrell, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Lang, Andrew F. “Victory is Our Only Road to Peace”: Texas, Wartime Morale, and Confederate Nationalism, 1860-1865. Master of Arts (History), May 2008, 148 pp., bibliography, 106 titles. This thesis explores the impact of home front and battlefield morale on Texas’s civilian and military population during the Civil War. It addresses the creation, maintenance, and eventual surrender of Confederate nationalism and identity among Texans from five different counties: Colorado, Dallas, Galveston, Harrison, and Travis. The war divided Texans into three distinct groups: civilians on the home front, soldiers serving in theaters outside of the state, and soldiers serving within Texas’s borders. Different environments, experiences, and morale affected the manner in which civilians and soldiers identified with the Confederate war effort. This study relies on contemporary letters, diaries, newspaper reports, and government records to evaluate how morale influenced national dedication and loyalty to the Confederacy among various segments of Texas’s population. Copyright 2008 by Andrew F. Lang ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Professors Richard Lowe, Randolph B. Campbell, and Richard B. McCaslin for their constant encouragement, assistance, and patience through every stage of this project. -

Unit 8 Test—Wed. Feb. 25

Unit 8 Study Guide: Pre-AP 2015 Civil War and Reconstruction Era (Ch. 15 & 16) Expectations of the Student/Essential Questions Identify the Civil War and Reconstruction Era of Texas History and define its characteristics Explain the significance of 1861 Explain reasons for the involvement of Texas in the Civil War such as states’ rights, slavery, secession, and tariffs Analyze the political, economic, and social effects of the Civil War and Reconstruction in Texas Identify significant individuals and events concerning Texas and the Civil War such as John Bell Hood, John Reagan, Francis Lubbock, Thomas Green, John Magruder and the Battle of Galveston, the Battle of Sabine Pass, and the Battle of Palmito Ranch Identify different points of view of political parties and interest groups on important Texas issues Essential Topics of Significance Essential People (5) Causes of Civil War Food shortages/ John Wilkes Booth Robert E. Lee substitutes Union vs. Conf. advantages Jefferson Davis Abraham Lincoln Appomattox Courthouse TX Secession Convention Dick Dowling Francis Lubbock State government collapse Fort Sumter “Juneteenth” John S. Ford John Magruder Battle of Galveston Freedmen’s Bureau Ulysses S. Grant Pendleton Murrah Battle of Sabine Pass (3) Recons. Plans Battle of Brownsville Thomas Green Elisha M. Pease (3) Recons. Amendments Red River Campaign Andrew Jackson Hamilton John Reagan (5) Provisions of Texas Battle of Palmito Ranch John Bell Hood Lawrence Sullivan Ross Constitution of 1869 Texans help for war effort Ironclad Oath Andrew Johnson Philip Sheridan Women’s roles Immigration/Emigration Albert Sidney Johnston James W. Throckmorton Essential Vocabulary Dates to Remember states’ rights preventive strike amendment Unit 8 Test—Wed. -

Official Texas Historical Marker with Post Travis County (Job #12TV06) Subject (Atlas) UTM: Location: 604 W 11Th St., Austin Texas 78701

Texas Historical Commission staff (BTW), 9/28/2012 18” x 28” Official Texas Historical Marker with post Travis County (Job #12TV06) Subject (Atlas) UTM: Location: 604 W 11th St., Austin Texas 78701 EDWARD CLARK HOUSE OUTBUILDING EDWARD CLARK (LT. GOVERNOR 1859- 1861; GOVERNOR 1861) PURCHASED FOUR LOTS, INCLUDING THIS PROPERTY, IN 1856. THIS BRICK STRUCTURE LIKELY SERVED AS AN OUTBUILDING, AND POSSIBLY AS SLAVE QUARTERS, DURING THE PERIOD CLARK LIVED IN THE ADJACENT HOME FROM 1856- 1867. THE LAYOUT OF THE HOME IS TYPICAL OF SLAVE QUARTERS FOR THE PERIOD AND COULD HAVE HOUSED THE TEN SLAVES CLARK OWNED. THE VERNACULAR, ONE- STORY LOAD-BEARING BRICK MASONRY BUILDING WAS CONSTRUCTED OF DOUBLE WYTHE, BUFF-COLORED AUSTIN COMMON BRICK. IN THE 1930s, ORIGINAL EXTERIOR FEATURES OF THE HOME WERE MODIFIED BY OWNER MAMIE HATZFELD. DESPITE THE CHANGES, IT IS A RARE SURVIVING EXAMPLE OF A PRE-CIVIL WAR RESIDENTIAL BUILDING. RECORDED TEXAS HISTORIC LANDMARK – 2012 MARKER IS PROPERTY OF THE STATE OF TEXAS RECORDED TEXAS HISTORIC LANDMARK MARKERS: 2012 Official Texas Historical Marker Sponsorship Application Form Valid September 1, 2011 to November 15, 2011 only This form constitutes a public request for the Texas Historical Commission (THC) to consider approval of an Official Texas Historical Marker for the topic noted in this application. The THC will review the request and make its determination based on rules and procedures of the program. Filing of the application for sponsorship is for the purpose of providing basic information to be used in the evaluation process. The final determination of eligibility and therefore approval for a state marker will be made by the THC. -

CIVILCIVIL WARWAR Leader in Implementing and Promoting Heritage Tourism Efforts in Texas

The Texas Historical Commission, the state agency for historic preservation, TEXASTEXAS administers a variety of programs to IN THE preserve the archeological, historical IN THE and cultural resources of Texas. Texas Heritage Trails Program The Texas Historical Commission is a CIVILCIVIL WARWAR leader in implementing and promoting heritage tourism efforts in Texas. The Texas Heritage Trails Program is the agency’s top tourism initiative. It’s like a whole other country. Our Mission To protect and preserve the state’s historic and prehistoric resources for the use, STORIES OF SACRIFICE, education, enjoyment, and economic benefit of present and future generations. VALOR, AND HOPE Copyright © 2013, Texas Historical Commission TEXAS HISTORICAL COMMISSION Texas in theCivil War The United States was rife with conflict and controversy in the years leading to the Civil War. Perhaps nowhere was the struggle more complex than in Texas. Some Texans supported the Union, but were concerned about political attacks on Southern institutions. Texas had been part of the United States just 15 years when secessionists prevailed in a statewide election. Texas formally seceded on March 2, 1861 to become the seventh state in the new Confederacy. Gov. Sam Houston was against secession, and struggled with loyalties to both his nation and his adopted state. His firm belief in the Union cost him his office when he refused to take anMarch oath of allegiance to the new government. 2, 1861 Gov. Sam Houston refused to declare loyalty to the Confederacy and was removed from office by the Texas secession convention in March 1861. SAM HOUSTON PORTRAIT Tensions were high when the Civil War began, and Texans responded in impressive numbers. -

The Secession Convention in Texas South and Europe Oppose Secession? Delegates Gathered in Austin on January 28, 1861

311 11/18/02 9:45 AM Page 304 Why It Matters Now 1 Texas Secedes Issues that led to the Civil War, such as civil rights and states’ rights, continue to affect us today. TERMS & NAMES OBJECTIVES MAIN IDEA Republican Party, 1. Identify the significance of the year Political and social issues divided tariff, Democratic Party, 1861. the country in the early 1860s. ordinance, Sam Houston, 2. Analyze the events that led up to Texas’s Many Southern states, including Abraham Lincoln, secession from the United States. Texas, decided to separate them- Edward Clark selves from the United States. WHAT Would You Do? Imagine that you are a Texas citizen who wants to voice your opinion Write your response about the political issues in 1860. You know that Texans will soon vote to Interact with History on whether or not to secede from the Union. Will you vote for or in your Texas Notebook. against secession? What reasons support your decision? tariff a tax placed on imported A Nation Divided or exported goods By 1860 Texas and several other Southern states were threatening to secede from the Union. The nation was clearly divided between the Northern and Southern states. Both sides were willing to fight for what they believed in, and the country soon found itself close to war. The Republican Party was formed in 1854 with one main goal—to stop the western spread of slavery. Party members believed slavery was counter to democracy and American ideals. Some members also hoped to end slavery in states where it already existed. -

Volume 3 Issue 10.Pub

SONS OF CONFEDERATE VETERANS, TEXAS DIVISION THE JOHN H. REAGAN CAMP NEWS www.reaganscvcamp.org VOLUME 3, ISSUE 10 OCTOBER 2011 CAMP MEETINGS COMMANDER’S DISPATCH 2nd Saturday of Each Month Compatriots, man all day long. 06:00 PM Light meal served at each meeting. 2nd Lt. Commander Rudy Ray Most of you have read this First Christian Church has a great historical program in January 2, 1864 quote by Ma- 113 East Crawford Street Palestine, Texas store for us at the October 8th jor General Patrick R. regular camp meeting. Major Cleburne C.S.A. before, but Turn north on N. Sycamore St. off of General John T. Furlow, U.S.A. whether you have or not, It is Spring St. (Hwy 19, 84,& 287)(across (Retired), CPA, CFE, will pre- so good, I would like to close from UP train station) travel three blocks, turn right on Crawford St., go sent a program on the 10th Tex- with its TRUTH: one block Church is on left as Infantry. I understand that he has authored a book that will be "... every man should endeav- Guests are welcome! Bring the family. published in the near future or to understand the meaning John H. Reagan about the 10th Texas Infantry. of subjugation before it is too About 1863 www.reaganscvcamp.org late. We can give but a faint Oct 8, 1818 – March 6, 1905 Last month’s program by Jerry idea when we say it means the Post Master General of the Con- Don Watt of Tatum, Texas, on loss of all we now hold most federate States of America “Confederate Guerilla Warfare” sacred .. -

Placelessness and the Rationale for Historic Preservation: National Contexts and East Texas Examples

East Texas Historical Journal Volume 43 Issue 2 Article 6 10-2005 Placelessness and the Rationale for Historic Preservation: National Contexts and East Texas Examples Jeffry A. Owens Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ethj Part of the United States History Commons Tell us how this article helped you. Recommended Citation Owens, Jeffry A. (2005) "Placelessness and the Rationale for Historic Preservation: National Contexts and East Texas Examples," East Texas Historical Journal: Vol. 43 : Iss. 2 , Article 6. Available at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ethj/vol43/iss2/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the History at SFA ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in East Texas Historical Journal by an authorized editor of SFA ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EAST TEXAS HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION 3 PLACELESSNESS AND THE RATIONALE FOR HISTORIC PRESERVATION: NATIONAL CONTEXTS AND EAST TEXAS EXAMPLES By Jeffrey A. Owens The spellcheckcT on my computer does not recognize "placelessness" as a word, and it is not in the unabridged dictionary. However, an internet search pulled 2,000 hits for the tenn, and the meaning is readily comprehended. "Placelessness" is a mental response to a generic environment. It can mean disorientation, caused by the disappearance of landmarks, or alienation, resulting from peoples' dislike of their surroundings. It describes a place with out heritage, one that lacks identity or is artificial and meaningless. Edward Relph coined the tenn in 1976 in Place and Placelessness, a study of envi ronmental philosophy. That same year, Yi-Fu Tuan, a geographer, founded the discipline of Human (i.e. -

Marshall Civil War History and Today the Town of Marshall, Texas Is Dedicated to Preserving Its Past; Given Its Eventful History, It Has Good Reason to Do So

Marshall Civil War History and Today The town of Marshall, Texas is dedicated to preserving its past; given its eventful history, it has good reason to do so. If you enjoy heritage tourism, this town is your ideal destination. The Civil War was one of the most significant periods in early American history and this East Texas town played a pivotal role throughout the era. With more slaves than any other county in Texas, the town was undeniably a Confederate community. Marshall served many purposes during the war. It was a major center of politics, military operations and supplier of necessities, especially gun powder. The town’s Confederate backing, as well as its location on the map, allowed it to serve as a power center west of the Mississippi, ideal for Confederate conferences. At one point, Marshall was the temporary capital of the Missouri Confederate Government that had been forced into exile. Today, a monument marks the site that once served as the house used by Missouri Governor Thomas C. Reynolds as his state’s Confederate “capitol.” Two of the three Texas governors who served during the Civil War, Edward Clark and Pendleton Murrah, were from Marshall. Much more can be said about the wartime role of this town; tourists eager to learn about this time in history are encouraged to stop by the Harrison County Historical Museum. You can also uncover this town’s Civil War past by visiting cemeteries and memorial sites dedicated to the town’s famous politicians and war heroes. If you are not exactly a history buff, no need to worry because the town is full of opportunities for a stimulating experience.