State Rights in Texas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sidney Sherman Chapter # 2, Sons of the Republic of Texas

Chapter President Chapter Treasurer Steve Manis Bill Mayo Chapter Vice President Media Robyn Davis Robert Gindratt Chapter Secretary Quartermaster Clark Wright Larry Armstrong Sidney Sherman Chapter #2 Minutes February 19, 2019 The Sidney Sherman Chapter #2, Sons of the Republic of Texas gathered at Kelley's Family Restaurant in Texas City before 6 PM. on February 19. Steve Manis opened the meeting at 6:33 PM. Vice president Robyn Davis provided us with an invocation and led us in the pledges to the United States and Texas Flags. New Members: Steve called James Hiroms to the podium and inducted him into the society. Then Steve called for Carol Mitchell, she was inducted as an honorary member of the chapter. Our president and his wife, Chaille, attend estate sales and during one they found a frame which they fitted with a photograph of Linda and Doug McBee, Doug being in his Confederates officer's uniform. Steve presented it to the couple. I think the photo was taken at the January ceremony that is held in the Episcopal Cemetery for remembrance of the Lea participation in the Battle of Galveston in 1863. Steve went around the room calling for guests. First, Mike Mitchell's wife, Carol was present. Doug McBee presented his wife Linda and a cousin Laura Shaffer. Chapter Members attending: Thomas Aucoin, Richard Barnes, Dan Burnett, Robyn Davis, Robert Gindratt (Media), Albert Seguin Gonzalez, Charlie Gordy, James Hiroms, J.B. Kline, Scott Lea MD, Steven Manis, Billy Mayo (Treasurer), Doug McBee, Jr., Mike Mitchell, Rodney Mize, Ron Schoolcraft, Clark Wright (Secretary). -

San Jacinto Battleground Award

THE BATTLE OF SAN JACINTO APRIL 21, 1836 San Jacinto Monument and Sam Houston Area Council Museum of History Boy Scouts of America SAM HOUSTON AREA COUNCIL BOY SCOUTS OF AMERICA INSTRUCTIONS FOR SAN JACINTO BATTLEFIELD HIKE Thank you for your interest in Texas heritage. We believe that this cooperative effort between the Sam Houston Area Council Boy Scouts and the State of Texas Parks and Wildlife Department will not only prove to be fun but highly interesting and instructive for all. This package includes a map of the San Jacinto Monument State Historical Park, five (5) sets of narratives to be read to your group at specific points during your hike, and a request for patches to be completed at the end of your hike. To qualify for the patch each participant must follow the trail as indicated on the map and participate (reading or listening) in each of the five (5) narratives at the proper points. Here's how it goes: 1. Get your pack, troop, crew, ship or post together on any day of the year preferably in uniform. 2. Drive to the San Jacinto Monument at the Historical Park in La Porte. Park in the parking provided around the monument. Disembark your unit and walk back to Point A (circled A). Reading Stops are defined on your map with circles around the numbers 1 through 5. Monuments are defined with squares around the numbers 1 through 20. 3. At Point 1 (Monument 11) have one or more of your group read History Stop Program Stop 1 narrative to the group. -

CASTRO's COLONY: EMPRESARIO COLONIZATION in TEXAS, 1842-1865 by BOBBY WEAVER, B.A., M.A

CASTRO'S COLONY: EMPRESARIO COLONIZATION IN TEXAS, 1842-1865 by BOBBY WEAVER, B.A., M.A. A DISSERTATION IN HISTORY Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved Accepted August, 1983 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I cannot thank all those who helped me produce this work, but some individuals must be mentioned. The idea of writing about Henri Castro was first suggested to me by Dr. Seymour V. Connor in a seminar at Texas Tech University. That idea started becoming a reality when James Menke of San Antonio offered the use of his files on Castro's colony. Menke's help and advice during the research phase of the project provided insights that only years of exposure to a subject can give. Without his support I would long ago have abandoned the project. The suggestions of my doctoral committee includ- ing Dr. John Wunder, Dr. Dan Flores, Dr. Robert Hayes, Dr. Otto Nelson, and Dr. Evelyn Montgomery helped me over some of the rough spots. My chairman, Dr. Alwyn Barr, was extremely patient with my halting prose. I learned much from him and I owe him much. I hope this product justifies the support I have received from all these individuals. 11 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ii LIST OF MAPS iv INTRODUCTION 1 Chapter I. THE EMPRESARIOS OF 1842 7 II. THE PROJECT BEGINS 39 III. A TOWN IS FOUNDED 6 8 IV. THE REORGANIZATION 97 V. SETTLING THE GRANT, 1845-1847 123 VI. THE COLONISTS: ADAPTING TO A NEW LIFE ... -

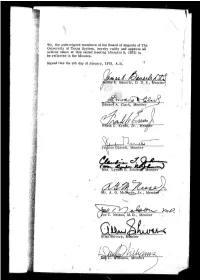

Board Minutes for January 9, 1973

1 ~6 ]. J We, the uudersigaed members of the Board of Regeats of The Uaiversity of Texas System, hereby ratify aad approve all z actions takea at this called meetiag (Jauuary 9, 1973) to be reflected in the Minutes. Signed this the 9Lh day of Jaauary, -1973, A.D. ol Je~ins Garrett, Member c • D., Member Allan( 'Shivers, M~mber ! ' /" ~ ° / ~r L ,.J J ,© Called Meeting Meeting No. 710 THE MINUTES OF THE BOARD OF REGENTS OF THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS SYSTEM Pages I and 2 O January ~, 1973 '~ Austin, Texas J~ 1511 ' 1-09-7) ~ETING NO. 710 TUESDAY, JANUARY 9, 1973.--Pursuant to the call of the Chair on January 6, 1973 (and which call appears in the Minutes of the meeting of that date), the Board of Regents convened in a Called Session at i:00 p.m~ on January 9, 1973, in the Library of the Joe C. Thompson Conference Center, The Uni- versity of Texas at Austin, Austin, Texas, with the follow- ing in attendance: ,t ATTENDANCE.-- Present Absent Regent James E. Baue-~ None Regent Edward Clark Regent Frank C. Erwin, Jr. "#~?::{ill Regent Jenkins Garrett Regent (Mrs.) Lyndon Johnson Regent A. G. McNeese, Jr. );a)~ Regent Joe T. Nelson Regent Allan Shivers Regent Dan C. Williams Secretary Thedford Chancellor LeMaistre Chancellor Emeritus Ransom Deputy Chancellor Walker (On January 5, 1973, Governor Preston Smith f~amed ~the < following members of the Board of Regents of The University of Texas System: ,~ ¢.Q .n., k~f The Honorable James E. Bauerle, a dentist of San Antonio, to succeed the Honorable John Peace of San Antonio, whose term had expired. -

Texas Office of Lt. Governor Data Sheet As of August 25, 2016

Texas Office of Lt. Governor Data Sheet As of August 25, 2016 History of Office The Office of the Lt. Governor of Texas was created by the State Constitution of 1845 and the office holder is President of the Texas Senate.1 Origins of the Office The Office of the Lt. Governor of Texas was established with statehood and the Constitution of 1845. Qualifications for Office The Council of State Governments (CSG) publishes the Book of the States (BOS) 2015. In chapter 4, Table 4.13 lists the Qualifications and Terms of Office for lieutenant governors: The Book of the States 2015 (CSG) at www.csg.org. Method of Election The National Lieutenant Governors Association (NLGA) maintains a list of the methods of electing gubernatorial successors at: http://www.nlga.us/lt-governors/office-of-lieutenant- governor/methods-of-election/. Duties and Powers A lieutenant governor may derive responsibilities one of four ways: from the Constitution, from the Legislature through statute, from the governor (thru gubernatorial appointment or executive order), thru personal initiative in office, and/or a combination of these. The principal and shared constitutional responsibility of every gubernatorial successor is to be the first official in the line of succession to the governor’s office. Succession to Office of Governor In 1853, Governor Peter Hansborough Bell resigned to take a seat in the U.S. House of Representatives and Lt. Governor James W. Henderson finished the unexpired term.2 In 1861, Governor Sam Houston was removed from office and Lt. Governor Edward Clark finished the unexpired term. In 1865, Governor Pendleton Murrah left office and Lt. -

2020-2022 Law School Catalog

The University of at Austin Law School Catalog 2020-2022 Table of Contents Examinations ..................................................................................... 11 Grades and Minimum Performance Standards ............................... 11 Introduction ................................................................................................ 2 Registration on the Pass/Fail Basis ......................................... 11 Board of Regents ................................................................................ 2 Minimum Performance Standards ............................................ 11 Officers of the Administration ............................................................ 2 Honors ............................................................................................... 12 General Information ................................................................................... 3 Graduation ......................................................................................... 12 Mission of the School of Law ............................................................ 3 Degrees ..................................................................................................... 14 Statement on Equal Educational Opportunity ................................... 3 Doctor of Jurisprudence ................................................................... 14 Facilities .............................................................................................. 3 Curriculum ................................................................................. -

NCPHS Journal Issue 70 (Winter 2000)

NORTH CAROLINA ~ POSTAL HISTORIAN The Journal of the North Carolina Postal History Society Volume 18, No.3 Winter 2000 Whole 70 North Carolina Ship Letters See President's Message - p2 Ajfi!Ulte #/55 ofthe American Philatelic Socie~P~ --. ._// . __ I_N_r_H_Is_l_s_s _u_E ______ ~---P_R_E_s_to_E_N_r_·s_M_E_s_s_A_G_E ~II~ _______ ~ The 19th annual meeting of the NCPHS will be held at A Dog's Tale WINPEX 2000 at the Elks Lodge in Winston-Salem on 29 April Tony L. Crumbley . 3 '-..,___./ 2000 at 2:00p.m. After a short business meeting, during which we Salisbury to Houston, Republic of Texas will elect new directors, I will give a slide program on North Richard F. Winter .. ............. .. ... ..... 5 Carolina ship letters. The annual meeting is one of the very few Pantego to Tuscarora - Two Remarkable R.P.O. Covers opportunities during the year that we have to visit with other Scott Troutman .............. .... ........ 7 NCPHS members and to meet new members. Although the A Three Cent Confederate Rate? meetings take very little time, not many members seem to want to Tony L. Crumbley .......... ....... ... 9 attend. WINPEX as it is not a very big show, but it is a very Pearl Diving in the Warren County Landfill friendly one and a good place to see old friends. Phil Perkinson ........................... 11 Vernon Stroupe and Tony Crumbley do a wonderful job for us as editors of the journal. We can not expect them to write all the articles that appear in the journal, however. We need more help from the members. I am sure most of our members have a cover ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• • that they particularly like. -

Smith, Ashbel

Published on NCpedia (https://www.ncpedia.org) Home > Smith, Ashbel Smith, Ashbel [1] Share it now! No votes yet Smith, Ashbel by James S. Brawley, 1994 13 Aug. 1805–21 Jan. 1886 A photograph of Dr. Ashbel Smith. Image from the Texas State Library. [2]Ashbel Smith, Salisbury physician and Texas political leader, was born in Hartford, Conn., the son of Phoebe Adams and Moses Smith, Jr. He had a half brother, Curtis, and three siblings, Henry Grattan, Caroline, and George Alfred. Ashbel Smith grew up in New England and was graduated with honors from Yale University in 1824. Afterwards he was induced by Charles Fisher [3] of Salisbury to teach in the Salisbury Academy [4] for a salary of $300 the first year plus his traveling expenses and board. His knowledge of the classics gained for him a wide reputation, and his Fourth of July oration in 1825 was published in Salisbury and Hartford newspapers, which both praised his erudition. During his first eighteen months in Salisbury, Smith formed many lifelong friends, among themB urton Craige [5], John Beard [6], J. J. Bruner [7], James Huie, and Jefferson Jones, but it was Charles Fisher who had the greatest influence on his life. Fisher was not only Smith's closest friend but his political mentor as well. Under Fisher's guidance, Smith began to read law but gave it up in 1826 to return north to study medicine at Yale. He took back with him two Salisbury boys, Archibald Henderson and Warren Huie, whom he tutored for Yale. After obtaining a medical degree in 1828, Smith practiced in Salisbury for three years. -

Vol. 22, Issue 1

Daughters of the Republic of Texas Volume 22, Issue 1 March 2009 Daughters’ Reflections President General’s BOM Nominations Committee Report Message This officer had a very busy summer and fall attending all the district work- shops except the two that were can- celled due to the hurricane and its aftermath. It was a very pleasant experience meeting members from all over Texas and seeing their dedica- tion to our organization and promot- ing its goals. Particularly heartwarm- ing were the chartering of the new chapter in Brady and two new CRT chapters in Brady and Laredo. We are expecting to be present for two other CRT charterings in Georgetown and Wichita Falls this spring thanks to the encouraging efforts of Faye Chism and Barbara Stevens. We have conducted two successful meetings electronically. The first one replaced the officers and Library Chairman who had resigned. We were fortunate to have dedicated Nominations Committee Members, Back row: Edith Shelinbarger, Lois Welch, Donna Johnson, Rowena Rose, Mary DRT members step up to fill the va- Walker and Sandra Meier. Seated: Jane Knapik, Jo Ann Moore, Gerry Smith and Eleanor Garrett. cancies (Carolyn Reed, 4th Vice President General, Sylvia Kennedy, This year’s Nominations Committee chose Chaplain General: #16268 Evelyn Rein- Historian General, and Connie Impel- to include every name nominated by their inger (Wm. B. Travis, VIII) man as Library Chairman). The sec- chapters who meets the qualifica- ond one ratified the appointments to tions. They present the following slate of Recording Secretary General: #23745 the Alamo Capital Campaign STF officers to be considered for election at the Stephanie P. -

Texas, Wartime Morale, and Confederate Nationalism, 1860-1865

“VICTORY IS OUR ONLY ROAD TO PEACE”: TEXAS, WARTIME MORALE, AND CONFEDERATE NATIONALISM, 1860-1865 Andrew F. Lang, B. A. Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2008 APPROVED: Richard G. Lowe, Major Professor Randolph B. Campbell, Committee Member Richard B. McCaslin, Committee Member Adrian R. Lewis, Chair of the Department of History Sandra L. Terrell, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Lang, Andrew F. “Victory is Our Only Road to Peace”: Texas, Wartime Morale, and Confederate Nationalism, 1860-1865. Master of Arts (History), May 2008, 148 pp., bibliography, 106 titles. This thesis explores the impact of home front and battlefield morale on Texas’s civilian and military population during the Civil War. It addresses the creation, maintenance, and eventual surrender of Confederate nationalism and identity among Texans from five different counties: Colorado, Dallas, Galveston, Harrison, and Travis. The war divided Texans into three distinct groups: civilians on the home front, soldiers serving in theaters outside of the state, and soldiers serving within Texas’s borders. Different environments, experiences, and morale affected the manner in which civilians and soldiers identified with the Confederate war effort. This study relies on contemporary letters, diaries, newspaper reports, and government records to evaluate how morale influenced national dedication and loyalty to the Confederacy among various segments of Texas’s population. Copyright 2008 by Andrew F. Lang ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Professors Richard Lowe, Randolph B. Campbell, and Richard B. McCaslin for their constant encouragement, assistance, and patience through every stage of this project. -

Chapter Vi Ashbel Smith-Gideon Lincecum Dr

CHAPTER VI ASHBEL SMITH-GIDEON LINCECUM DR. ASHBEL SMITH There are a few characters that flash like a meteor across the pages of history. In the star-dust of their trail ever scintillate the accomplishments of their brief span of years in this hurrying world. Such a character was Dr. Ashbel Smith. Small of stature, keen of mind, ever in the forefront of public affairs,' he was a scholar, statesman, diplomat, soldier, farmer and physician. As a scholar, he held the degrees of B. A., M. A. from Yale at the age of nine teen years, 1824. He later studied both law and medicine, and was a skilled surgeon. He came to Texas a few months after the Battle of San Jacinto, and was appointed Surgeon General of the Texan Army. A close personal friend of Sam Houston, he oc cupied for several years the same room with him in that celebrated log house, the home of the President. His splendid intellect was often of valuable assistance to those earnest men who were creating a new nation. His in fluence in the enactment of laws regulating the practice of law and medicine was needed and accepted; this same influence was used in the establishment of our great Uni versity and the early medical schools. Dr. Smith was one of the organizers of the University of Texas and served many years as a regent and President of the Board of Regents. He wrote many medical treatises that were published in this country and abroad. His final great mental attainment was the valued assistance he gave as collaborator of the American revised version of the Bible, published shortly before his death, 1885. -

East End Historical Markers Driving Tour

East End Historical Markers Driving Tour Compiled by Will Howard Harris County Historical Commission, Heritage Tourism Chair 2015 TABLE OF CONTENTS DOWNTOWN – Harris County NORTHWEST CORNER – German Texans Frost Town 512 McKee: MKR Frost Town 1900 Runnels: MKR Barrio El Alacran 2115 Runnels: Mkr: Myers-Spalti Manufacturing Plant (now Marquis Downtown Lofts) NEAR NAVIGATION – Faith and Fate 2405 Navigation: Mkr: Our Lady of Guadalupe Catholic Church 2407 Navigation: Mkr in cemetery: Samuel Paschall BRADY LAND: Magnolias and Mexican Americans MKR Quiosco, Mkr for Park [MKR: Constitution Bend] [Houston’s Deepwater Port] 75th & 76th: 1400 @ J &K, I: De Zavala Park and MKR 76th St 907 @ Ave J: Mkr: Magnolia Park [MKR: League of United Latin American Citizens, Chapter 60] Ave F: 7301: MKR Magnolia Park City Hall / Central Fire Station #20 OLD TIME HARRISBURG 215 Medina: MKR Asbury Memorial United Methodist Church 710 Medina @ Erath: Mkr: Holy Cross Mission (Episcopal) 614 Broadway @ E Elm, sw cor: MKR Tod-Milby Home site 8100 East Elm: MKR Buffalo Bayou, Brazos & Colorado RR 620 Frio: MKR Jane Briscoe Harris Home site Magnolia 8300 across RR: Mkr, Glendale Cemetery Magnolia 8300, across RR: Mkr, Site of Home of General Sidney Sherman [Texas Army Crossed Buffalo Bayou] [Houston Yacht Club] Broadway 1001 @ Lawndale: at Frost Natl Bk, with MKR “Old Harrisburg” 7800 @ 7700 Bowie: MKR Harrisburg-Jackson Cemetery East End Historical Makers Driving Tour 1 FOREST PARK CEMETERY [Clinton @ Wayside: Mkr: Thomas H. Ball, Jr.] [Otherwise Mkr: Sam (Lighnin’) Hopkins] THE SOUTHERN RIM: Country Club and Eastwood 7250 Harrisburg: MKR Immaculate Conception Catholic Church Brookside Dr.