ETHJ Vol-11 No-2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

It044 130000-147525

Ronald Reagan Presidential Library Digital Library Collections This is a PDF of a folder from our textual collections. WHORM Subject File Code: IT044 (International Monetary Fund) Case file Number(s): 130000 -147525 To see more digitized collections visit: https://www.reaganlibrary.gov/archives/digitized-textual-material To see all Ronald Reagan Presidential Library inventories visit: https://www.reaganlibrary.gov/archives/white-house-inventories Contact a reference archivist at: [email protected] Citation Guidelines: https://reaganlibrary.gov/archives/research- support/citation-guide National Archives Catalogue: https://catalog.archives.gov/ -., J 31193 ID#______ _ WHITE HOUSE CORRESPONDENCE TRACKING WORKSHEET D O · OUTGOING D H · INTERNAL ~ I • INCOMING Date Correspondence c? O> , Received(YY/MM/DD) a3/ ~ /~/ Name of Correspondent: ~~ /.(/al/~ □ Ml Mail Report User Codes: (A>--~- (B) ____ (C) ____ S~t: ftr~ft:h;~z:i~~J ROUTE TO: ACTION DISPOSITION Tracking Type Completion Action Date of Date Office/Agency (Staff Name) Code YY/MM/DD Response Code YY/MM/DD QJ>-, - -----'----------- ~- /( J) /} 8'3> IJf- ~ ½faJe ORIGINATOR Referral Note: I) 5 T tZ )}\(\,)\.,\)1-<L I rJ ~- & fi~f1~.({ ~ Referral Note:- ·• LA-"D"'-<o e- C, 83 ,01/,J:J... q, Referral Note: Referral Note: Referral Note: ACTION CODES: ' DISPOSITION CODES: A - Appropriate Action I - Info Copy Only/No Action Necessary A - Answered C - Completed C - Comment/Recommendation R - Direct Reply w/Copy B - Non-Special Referral S - Suspended D - Draft Response S - For Signature F - Furnish Fact Sheet X - Interim Reply to be used as Enclosure FOR OUTGOING CORRESPONDENCE: Type of Response = Initials of Signer Code = "A" Completion Date = Date of Outgoing Comments: _____________________________________ Keep this worksheet attached to the original incoming letter. -

Opinion Vs William B

/•/ Pog«2, Thursday, F0bruarY9, 1984, Th»H*adllght \y^., rhursdoy, February 9, IM4, Thm HmadH^t. fagm 3 YOUR VOTE COUNTS Colorado County Courthouse Report DISTRICT COURT 31,^ Columbua, «nd Patricia SUrrSFlLED Gift Cowart CoTiatructi»» a Eitata^ Mortimer G. Jean Mohon Jacobe, '28, Obenhaus, Jr. et ux'to Company to Le«H« '.] Helen M. Hattermann Columbus; 2-1-84. M-tJu" ^'- -Deceased —ONLY IF YOU ARE REGISTERED AND VOTE!! — 'JBeinhauer vs. Albert J. Richard R Obenhaua, un Weishuhn ^t ux. 1.900 M"'ldt R. Sullivan Be Our Jon Luther Knight, 28, Beinhauer; divorce; 127-84. divided interest to-wit, 100 acres, James Cummins Executor to Mitchell Schulenburg. and Deborah acres, John Hadden Survey. 1-17-84 «''"•'•» Corporation, 160 Ruby Lee (Becky) Pauline McGinty. 25. *"«. W. S. Delaney REGISTER BY MARCH 8lh - Voter Reglslrallon Foims Available at the Firet National Bank Wilburn ^d husband vs Survey. 1-17-84 Deed. Lillian Guinn «t al Schulenburg; 2-2-84. Gift deed, Gus F. to Delores Hartfiel Survey. 1M« VALENTINE General Motors Corp.; per MEMBER 1984 NEWS DEADLINE Micliael Switalski, 31. Obenhaua Jr. et ux to Mary Dabelgott,et al. 8 acres. H. Josephine Stanton sonal injikies; 1-27-84. .Weimar, and Patricia P. This opiaion page it meant to be a iharing of ideas, not Jast the Ellen Obenhaua Bolton, un M. McElroy Survey. 9*83 Sterb. to MitcheU"tnergy •^^/f^ 5 P.M. MONDAY Thea W^eks vs Thom Piper, 26, Weimar; 2-2-84. writer's views. It's objective is to stimulate thought* of readers divided interest to-wit, Deed. -

Govenor Miriam A. Ferguson

East Texas Historical Journal Volume 17 Issue 2 Article 5 10-1979 Govenor Miriam A. Ferguson Ralph W. Steen Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ethj Part of the United States History Commons Tell us how this article helped you. Recommended Citation Steen, Ralph W. (1979) "Govenor Miriam A. Ferguson," East Texas Historical Journal: Vol. 17 : Iss. 2 , Article 5. Available at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ethj/vol17/iss2/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the History at SFA ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in East Texas Historical Journal by an authorized editor of SFA ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EAST TEXAS HISTORICAL ASSOCIAnON 3 GOVERNOR MIRIAM A. FERGUSON by Ralph W. Steen January 20, 1925 was a beautiful day in Austin, Texas, and thousands of people converged on the city to pay tribute to the first woman to serve the state as governor. Long before time for the inaugural ceremony to begin every space in the gallery of the House of Representatives was taken and thousands who could not gain admission blocked hanways and stood outside the capitol. After brief opening ceremonies, Chief Justice C.M. Cureton administered the oath of office to Lieutenant Governor Barry Miller and then to Governor Miriam A. Ferguson. Pat M. Neff, the retiring governor, introduced Mrs. Ferguson to the audience and she delivered a brief inaugural address. The governor called for heart in government, proclaimed political equality for women, and asked for the good will and the prayers of the women of Texas. -

Speakers of the House: Elections, 1913-2021

Speakers of the House: Elections, 1913-2021 Updated January 25, 2021 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov RL30857 Speakers of the House: Elections, 1913-2021 Summary Each new House elects a Speaker by roll call vote when it first convenes. Customarily, the conference of each major party nominates a candidate whose name is placed in nomination. A Member normally votes for the candidate of his or her own party conference but may vote for any individual, whether nominated or not. To be elected, a candidate must receive an absolute majority of all the votes cast for individuals. This number may be less than a majority (now 218) of the full membership of the House because of vacancies, absentees, or Members answering “present.” This report provides data on elections of the Speaker in each Congress since 1913, when the House first reached its present size of 435 Members. During that period (63rd through 117th Congresses), a Speaker was elected six times with the votes of less than a majority of the full membership. If a Speaker dies or resigns during a Congress, the House immediately elects a new one. Five such elections occurred since 1913. In the earlier two cases, the House elected the new Speaker by resolution; in the more recent three, the body used the same procedure as at the outset of a Congress. If no candidate receives the requisite majority, the roll call is repeated until a Speaker is elected. Since 1913, this procedure has been necessary only in 1923, when nine ballots were required before a Speaker was elected. -

Tip O'neill: Irish-American Representative Man (2003)

New England Journal of Public Policy Volume 28 Issue 1 Assembled Pieces: Selected Writings by Shaun Article 14 O'Connell 11-18-2015 Tip O’Neill: Irish-American Representative Man (2003) Shaun O’Connell University of Massachusetts Boston, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.umb.edu/nejpp Part of the Political History Commons Recommended Citation O’Connell, Shaun (2015) "Tip O’Neill: Irish-American Representative Man (2003)," New England Journal of Public Policy: Vol. 28: Iss. 1, Article 14. Available at: http://scholarworks.umb.edu/nejpp/vol28/iss1/14 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks at UMass Boston. It has been accepted for inclusion in New England Journal of Public Policy by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at UMass Boston. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Tip O’Neill: Irish American Representative Man Thomas P. “Tip” O’Neill, Man of the House as he aptly called himself in his 1987 memoir, stood as the quintessential Irish American representative man for half of the twentieth century. O’Neill, often misunderstood as a parochial, Irish Catholic party pol, was a shrewd, sensitive, and idealistic man who came to stand for a more inclusive and expansive sense of his region, his party, and his church. O’Neill’s impressive presence both embodied the clichés of the Irish American character and transcended its stereotypes by articulating a noble vision of inspired duty, determined responsibility, and joy in living. There was more to Tip O’Neill than met the eye, as several presidents learned. -

Pojoaque Valley Schools Social Studies CCSS Pacing Guide 7 Grade

Pojoaque Valley Schools Social Studies CCSS Pacing Guide 7th Grade *Skills adapted from Kentucky Department of Education ** Evidence of attainment/assessment, Vocabulary, Knowledge, Skills and Essential Elements adapted from Wisconsin Department of Education and Standards Insights Computer-Based Program Version 2 2016- 2017 ADVANCED CURRICULUM – 7th GRADE (Social Studies with ELA CCSS and NGSS) Version 2 1 Pojoaque Valley Schools Social Studies Common Core Pacing Guide Introduction The Pojoaque Valley Schools pacing guide documents are intended to guide teachers’ use of New Mexico Adopted Social Studies Standards over the course of an instructional school year. The guides identify the focus standards by quarter. Teachers should understand that the focus standards emphasize deep instruction for that timeframe. However, because a certain quarter does not address specific standards, it should be understood that previously taught standards should be reinforced while working on the focus standards for any designated quarter. Some standards will recur across all quarters due to their importance and need to be addressed on an ongoing basis. The Standards are not intended to be a check-list of knowledge and skills but should be used as an integrated model of literacy instruction to meet end of year expectations. The Social Studies CCSS pacing guides contain the following elements: • Strand: Identify the type of standard • Standard Band: Identify the sub-category of a set of standards. • Benchmark: Identify the grade level of the intended standards • Grade Specific Standard: Each grade-specific standard (as these standards are collectively referred to) corresponds to the same-numbered CCR anchor standard. Put another way, each CCR anchor standard has an accompanying grade-specific standard translating the broader CCR statement into grade- appropriate end-of-year expectations. -

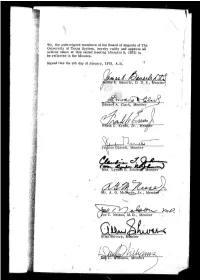

Board Minutes for January 9, 1973

1 ~6 ]. J We, the uudersigaed members of the Board of Regeats of The Uaiversity of Texas System, hereby ratify aad approve all z actions takea at this called meetiag (Jauuary 9, 1973) to be reflected in the Minutes. Signed this the 9Lh day of Jaauary, -1973, A.D. ol Je~ins Garrett, Member c • D., Member Allan( 'Shivers, M~mber ! ' /" ~ ° / ~r L ,.J J ,© Called Meeting Meeting No. 710 THE MINUTES OF THE BOARD OF REGENTS OF THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS SYSTEM Pages I and 2 O January ~, 1973 '~ Austin, Texas J~ 1511 ' 1-09-7) ~ETING NO. 710 TUESDAY, JANUARY 9, 1973.--Pursuant to the call of the Chair on January 6, 1973 (and which call appears in the Minutes of the meeting of that date), the Board of Regents convened in a Called Session at i:00 p.m~ on January 9, 1973, in the Library of the Joe C. Thompson Conference Center, The Uni- versity of Texas at Austin, Austin, Texas, with the follow- ing in attendance: ,t ATTENDANCE.-- Present Absent Regent James E. Baue-~ None Regent Edward Clark Regent Frank C. Erwin, Jr. "#~?::{ill Regent Jenkins Garrett Regent (Mrs.) Lyndon Johnson Regent A. G. McNeese, Jr. );a)~ Regent Joe T. Nelson Regent Allan Shivers Regent Dan C. Williams Secretary Thedford Chancellor LeMaistre Chancellor Emeritus Ransom Deputy Chancellor Walker (On January 5, 1973, Governor Preston Smith f~amed ~the < following members of the Board of Regents of The University of Texas System: ,~ ¢.Q .n., k~f The Honorable James E. Bauerle, a dentist of San Antonio, to succeed the Honorable John Peace of San Antonio, whose term had expired. -

Texas Office of Lt. Governor Data Sheet As of August 25, 2016

Texas Office of Lt. Governor Data Sheet As of August 25, 2016 History of Office The Office of the Lt. Governor of Texas was created by the State Constitution of 1845 and the office holder is President of the Texas Senate.1 Origins of the Office The Office of the Lt. Governor of Texas was established with statehood and the Constitution of 1845. Qualifications for Office The Council of State Governments (CSG) publishes the Book of the States (BOS) 2015. In chapter 4, Table 4.13 lists the Qualifications and Terms of Office for lieutenant governors: The Book of the States 2015 (CSG) at www.csg.org. Method of Election The National Lieutenant Governors Association (NLGA) maintains a list of the methods of electing gubernatorial successors at: http://www.nlga.us/lt-governors/office-of-lieutenant- governor/methods-of-election/. Duties and Powers A lieutenant governor may derive responsibilities one of four ways: from the Constitution, from the Legislature through statute, from the governor (thru gubernatorial appointment or executive order), thru personal initiative in office, and/or a combination of these. The principal and shared constitutional responsibility of every gubernatorial successor is to be the first official in the line of succession to the governor’s office. Succession to Office of Governor In 1853, Governor Peter Hansborough Bell resigned to take a seat in the U.S. House of Representatives and Lt. Governor James W. Henderson finished the unexpired term.2 In 1861, Governor Sam Houston was removed from office and Lt. Governor Edward Clark finished the unexpired term. In 1865, Governor Pendleton Murrah left office and Lt. -

Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University In

371 /V8 A/O 'oo THE "VIVA KENNEDY" CLUBS IN SOUTH TEXAS THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Joan Traffas, B.A. Denton, Texas December, 1972 Traffas, Joan, The "Viva Kennedy" Clubs in South Texas. Master of Arts (History), December, 1972, 132 pp., 2 tables, bibliography, 115 titles. This thesis analyzes the impact of the Mexican-American voters in south Texas on the 1960 presidential election. During that election year, this ethnic minority was strong enough to merit direct appeals from the Democratic presiden- tial candidate, and subsequently, allowed to conduct a unique campaign divorced from the direct control of the conservative state Democratic machinery. Formerly, the Democratic politicos in south Texas manipulated the Mexican-American vote. In 1960, however, the Chicanos voted for a man with whom they could empathize, rather than for a party label. This strong identification with the Democratic candidate was rooted in psychological rather than ideological, social rather than political, factors. John F. Kennedy seemed to personify machismo and simpatla. Perhaps even more impres- sive than the enthusiasm, the Kennedy candidacy generated among the Mexican-Americans was the ability of the Texas Democratic regulars to prevent a liberal-conservative rup- ture within the state party. This was accomplished by per- mitting the Mexican-American "Viva Kennedy" clubs quasi- independence. Because of these two conditions, the Mexican- American ethnic minority became politically salient in the 1960 campaign. 1 2 The study of the Mexican-American political behavior in 1960 proceeds in three stages. -

2020-2022 Law School Catalog

The University of at Austin Law School Catalog 2020-2022 Table of Contents Examinations ..................................................................................... 11 Grades and Minimum Performance Standards ............................... 11 Introduction ................................................................................................ 2 Registration on the Pass/Fail Basis ......................................... 11 Board of Regents ................................................................................ 2 Minimum Performance Standards ............................................ 11 Officers of the Administration ............................................................ 2 Honors ............................................................................................... 12 General Information ................................................................................... 3 Graduation ......................................................................................... 12 Mission of the School of Law ............................................................ 3 Degrees ..................................................................................................... 14 Statement on Equal Educational Opportunity ................................... 3 Doctor of Jurisprudence ................................................................... 14 Facilities .............................................................................................. 3 Curriculum ................................................................................. -

THE HOWLING DAWG Recapping the Events of AUGUST 2017

THE HOWLING DAWG Recapping the events of AUGUST 2017 “Defiant, still” 16th Georgia Volunteer Infantry Regiment, Company G "The Jackson Rifles" THE WAR IN THE FAR WEST Re-enactment of The Battle of Picacho Pass (Arizona) Recently I heard someone mention The Battle of Picacho Pass (Arizona) as being the most western part of North America that War Between the States fighting occurred. I was surprised even though I knew Washington State furnished a Union Regiment as did Nebraska, Colorado, Dakota and the Oklahoma Territory. Often the Union cavalry forces that John S. Mosby fought against in Virginia hailed from California. I had always thought that The Battle of Glorieta Pass, fought from March 26– 28, 1862, in the northern New Mexico Territory was the far western reaches of hostility. I looked up The Battle of Picacho Pass and learned that the April 15, 1862 action occurred around Picacho Peak, 50 miles northwest of Tucson, Arizona. It was fought between a Union cavalry patrol from California and a party of Confederate pickets from Tucson. After a Confederate force of about 120 cavalrymen arrived at Tucson from Texas on February 28, 1862, they proclaimed Tucson the capital of the western district of the Confederate Arizona Territory, which comprised what is now southern Arizona and southern New Mexico. Mesilla, near Las Cruces, was declared the territorial capital and seat of the eastern district of the territory. The property of Tucson Unionists was confiscated and they were jailed or driven out of town. Confederates hoped a flood of sympathizers in southern California would join them and give the Confederacy an outlet on the Pacific Ocean, but this never happened. -

DISSERTATION Presented to the Graduate Council of the North

4Z SAM RAYBURN: TRIALS OF A PARTY MAN DISSERTATION Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By Edward 0. Daniel, B.A., M.A. Denton, Texas May, 1979 Daniel, Edward 0., Sam Rayburn: Trials of a Party Man. Doctor of Philosophy (History), May, 1979, 330 pp., bibliog- raphy, 163 titles. Sam Rayburn' s remarkable legislative career is exten- sively documented, but no one has endeavored to write a political biography in which his philosophy, his personal convictions, and the forces which motivated him are analyzed. The object of this dissertation is to fill that void by tracing the course of events which led Sam Rayburn to the Speakership of the United States House of Representatives. For twenty-seven long years of congressional service, Sam Rayburn patiently, but persistently, laid the groundwork for his elevation to the speakership. Most of his accomplish- ments, recorded in this paper, were a means to that end. His legislative achievements for the New Deal were monu- mental, particularly in the areas of securities regulation, progressive labor laws, and military preparedness. Rayburn rose to the speakership, however, not because he was a policy maker, but because he was a policy expeditor. He took his orders from those who had the power to enhance his own station in life. Prior to the presidential election of 1932, the center of Sam Rayburn's universe was an old friend and accomplished political maneuverer, John Nance Garner. It was through Garner that Rayburn first perceived the significance of the "you scratch my back, I'll scratch yours" style of politics.