Suffrage and the Great Pilgrimage in Yorkshire, 1913

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Issue 61 Autumn/Winter 2009 Issn 1476-6760

Issue 61 Autumn/Winter 2009 Issn 1476-6760 Faridullah Bezhan on Gender and Autobiography Rosalind Carr on Scottish Women and Empire Nicola Cowmeadow on Scottish Noblewomen’s Political Activity in the 18th C Katie Barclay on Family Legacies Huw Clayton on Police Brutality Allegations Plus Five book reviews Call for Reviewers Prizes WHN Conference Reports Committee News www.womenshistorynetwork.org Women’s History Network 19th Annual Conference 2009 Performing the Self: Women’s Lives in Historical Perspective University of Warwick, 10-12 September 2010 Papers are invited for the 19th Annual Conference 2010 of the Women’s History Network. The idea that selfhood is performed has a very long tradition. This interdisciplinary conference will explore the diverse representations of women’s identities in the past and consider how these were articulated. Papers are particularly encouraged which focus upon the following: ■ Writing women’s histories ■ Gender and the politics of identity ■ Ritual and performance ■ The economics of selfhood: work and identity ■ Feminism and auto/biography ■ Performing arts ■ Teaching women’s history For more information please contact Dr Sarah Richardson: [email protected], Department of History, University of Warwick, Coventry CV4 7AL. Abstracts of papers (no more than 300 words) should be submitted to [email protected] The closing date for abstracts is 5th March 2010. Conference website: www2.warwick.ac.uk/fac/arts/history/res_rec/ conferences/whn Further information and a conference call will be posted on the WHN website www.womenshistorynetwork.org Editorial elcome to the Autumn/Winter 2009 edition of reproduced in full. We plan to publish the Carol Adams WWomen’s History Magazine. -

Suffragette: the Battle for Equality Author/ Illustrator: David Roberts Publisher: Two Hoots (2018)

cilip KATE GREENAWAY shortlist 2019 shadowing resources CILIP Kate Greenaway Medal 2019 VISUAL LITERACY NOTES Title: Suffragette the Battle for Equality Author/ Illustrator: David Roberts Publisher: Two Hoots First look This is a nonfiction book about the women and men who fought for women’s rights at the beginning of the 20th Century. It is packed with information – some that we regularly read or hear about, and some that is not often highlighted regarding this time in history. There may not be time for every shadower to read this text as it is quite substantial, so make sure they have all shared the basic facts before concentrating on the illustrations. Again, there are a lot of pictures so the following suggestions are to help to navigate around the text to give all shadowers a good knowledge of the artwork. After sharing a first look through the book ask for first responses to Suffragette before looking in more detail. Look again It is possible to group the illustrations into three categories. Find these throughout the book; 1. Portraits of individuals who either who were against giving women the vote or who were involved in the struggle. Because photography was becoming established we can see photos of these people. Some of them are still very well-known; for example, H.H. Asquith, Prime Minister from 1908 to 1916 and Winston Churchill, Home Secretary from 1910 to 1911. They were both against votes for women. Other people became well-known because they were leading suffragettes; for example, Christabel Pankhurst and Annie Kenney. 2. -

TRANSNATIONAL SMYTH: SUFFRAGE, COSMOPOLITANISM, NETWORKS Erica Fedor a Thesis Submitted to the Faculty at the University Of

TRANSNATIONAL SMYTH: SUFFRAGE, COSMOPOLITANISM, NETWORKS Erica Fedor A thesis submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Music. Chapel Hill 2018 Approved by: Annegret Fauser David Garcia Tim Carter © 2018 Erica Fedor ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Erica Fedor: Transnational Smyth: Suffrage, Cosmopolitanism, Networks (Under the direction of Annegret Fauser) This thesis examines the transnational entanglements of Dame Ethel Smyth (1858–1944), which are exemplified through her travel and movement, her transnational networks, and her music’s global circulation. Smyth studied music in Leipzig, Germany, as a young woman; composed an opera (The Boatswain’s Mate) while living in Egypt; and even worked as a radiologist in France during the First World War. In order to achieve performances of her work, she drew upon a carefully-cultivated transnational network of influential women—her powerful “matrons.” While I acknowledge the sexism and misogyny Smyth encountered and battled throughout her life, I also wish to broaden the scholarly conversation surrounding Smyth to touch on the ways nationalism, mobility, and cosmopolitanism contribute to, and impact, a composer’s reputations and reception. Smyth herself acknowledges the particular double-bind she faced—that of being a woman and a composer with German musical training trying to break into the English music scene. Using Ethel Smyth as a case study, this thesis draws upon the composer’s writings, reviews of Smyth’s musical works, popular-press articles, and academic sources to examine broader themes regarding the ways nationality, transnationality, and locality intersect with issues of gender and institutionalized sexism. -

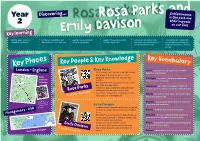

Rosa Parks and Emily Davison

Year Achievements Discovering... in the past and 2 Rosa Parks andtheir impacts Emily Davison on our lives Key learning Identify what makes an Recognise similarities and Explain how Rosa Parks Explain how Emily Davison Recognise similarities and Understand and explain the individual significant. differences to 1955 and now. became significant. became significant. differences about RP and ED impact that Rosa Parks and and their achievements. Emily Davison had on modern society. Key Vocabulary Key Places Key People & Key Knowledge Rosa Parks Activist – a person who campaigns to bring about London - England • Civil rights activist in the mid to late 20th Century. political or social change. • She refused to give up her seat to a white Emily passenger on December 1st, 1955 and was Civil Rights – the rights of citizens to political and Davison’s arrested. social freedom and equality. birthplace • This launched the Montgomery bus boycott (5th Dec, 1995-20th Dec, 1996) Segregation – the enforced separation of different • At this time, black people were segregated and racial groups in a country, community or establishment. discriminated for the colour of their skin. Rosa Parks • Rosa Parks changed laws on segregation in the Equality – the state of being equal, especially in status. Feb 4, 1913 – Oct 24, 2005 USA, starting with transportation. Rights and opportunities. Carlisle Park, Prejudice – preconceived opinion that is not based on Northumberland reason or actual experience. – Statue of Emily Emily Davison Davison • A women’s equal rights activist who quit her job as a teacher to join the Women’s Social and Political Boycott – withdraw from something in protest. -

Civil War in the Delta: Environment, Race, and the 1863 Helena Campaign George David Schieffler University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Theses and Dissertations 8-2017 Civil War in the Delta: Environment, Race, and the 1863 Helena Campaign George David Schieffler University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Schieffler, George David, "Civil War in the Delta: Environment, Race, and the 1863 Helena Campaign" (2017). Theses and Dissertations. 2426. http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/2426 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Civil War in the Delta: Environment, Race, and the 1863 Helena Campaign A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History by George David Schieffler The University of the South Bachelor of Arts in History, 2003 University of Arkansas Master of Arts in History, 2005 August 2017 University of Arkansas This dissertation is approved for recommendation to the Graduate Council. ____________________________________ Dr. Daniel E. Sutherland Dissertation Director ____________________________________ ____________________________________ Dr. Elliott West Dr. Patrick G. Williams Committee Member Committee Member Abstract “Civil War in the Delta” describes how the American Civil War came to Helena, Arkansas, and its Phillips County environs, and how its people—black and white, male and female, rich and poor, free and enslaved, soldier and civilian—lived that conflict from the spring of 1861 to the summer of 1863, when Union soldiers repelled a Confederate assault on the town. -

Liña Do Tempo

Documento distribuído por Álbum de mulleres Liña do tempo http://culturagalega.org/album/linhadotempo.php 11ª versión (13/02/2017) Comisión de Igualdade Pazo de Raxoi, 2º andar. 15705 Santiago de Compostela (Galicia) Tfno.: 981957202 / Fax: 981957205 / [email protected] GALICIA MEDIEVO - No mundo medieval, as posibilidades que se ofrecen ás mulleres de escoller o marco en que han de desenvolver o seu proxecto de vida persoal son fundamentalmente tres: matrimonio, convento ou marxinalidade. - O matrimonio é a base das relacións de parentesco e a clave das relacións sociais. Os ritos do matrimonio son instituídos para asegurar un sistema ordenado de repartimento de mulleres entre os homes e para socializar a procreación. Designando quen son os pais engádese outra filiación á única e evidente filiación materna. Distinguindo as unións lícitas das demais, as crianzas nacidas delas obteñen o estatuto de herdeiras. - Século IV: Exeria percorre Occidente, á par de recoller datos e escribir libros de viaxes. - Ata o século X danse casos de comunidades monásticas mixtas rexidas por abade ou abadesa. - Entre os séculos IX e X destacan as actividades de catro mulleres da nobreza galega (Ilduara Eriz, Paterna, Guntroda e Aragonta), que fan delas as principais e máis cualificadas aristócratas galegas destes séculos. - Entre os séculos IX e XII chégase á alianza matrimonial en igualdade de condicións, posto que o sistema de herdanza non distingue entre homes e mulleres; o matrimonio funciona máis como instrumento asociativo capaz de crear relacións amplas entre grupos familiares coexistentes que como medio que permite relacións de control ou protección de carácter vertical. - Século X: Desde mediados de século, as mulleres non poden testificar nos xuízos e nos documentos déixase de facer referencia a elas. -

Process Paper and Bibliography

ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY Primary Sources Books Kenney, Annie. Memories of a Militant. London: Edward Arnold & Co, 1924. Autobiography of Annie Kenney. Lytton, Constance, and Jane Warton. Prisons & Prisoners. London: William Heinemann, 1914. Personal experiences of Lady Constance Lytton. Pankhurst, Christabel. Unshackled. London: Hutchinson and Co (Publishers) Ltd, 1959. Autobiography of Christabel Pankhurst. Pankhurst, Emmeline. My Own Story. London: Hearst’s International Library Co, 1914. Autobiography of Emmeline Pankhurst. Newspaper Articles "Amazing Scenes in London." Western Daily Mercury (Plymouth), March 5, 1912. Window breaking in March 1912, leading to trials of Mrs. Pankhurst and Mr. & Mrs. Pethick- Lawrence. "The Argument of the Broken Pane." Votes for Women (London), February 23, 1912. The argument of the stone: speech delivered by Mrs Pankhurst on Feb 16, 1912 honoring released prisoners who had served two or three months for window-breaking demonstration in November 1911. "Attempt to Burn Theatre Royal." The Scotsman (Edinburgh), July 19, 1912. PM Asquith's visit hailed by Irish Nationalists, protested by Suffragettes; hatchet thrown into Mr. Asquith's carriage, attempt to burn Theatre Royal. "By the Vanload." Lancashire Daily Post (Preston), February 15, 1907. "Twenty shillings or fourteen days." The women's raid on Parliament on Feb 13, 1907: Christabel Pankhurst gets fourteen days and Sylvia Pankhurst gets 3 weeks in prison. "Coal That Cooks." The Suffragette (London), July 18, 1913. Thirst strikes. Attempts to escape from "Cat and Mouse" encounters. "Churchill Gives Explanation." Dundee Courier (Dundee), July 15, 1910. Winston Churchill's position on the Conciliation Bill. "The Ejection." Morning Post (London), October 24, 1906. 1 The day after the October 23rd Parliament session during which Premier Henry Campbell- Bannerman cold-shouldered WSPU, leading to protest led by Mrs Pankhurst that led to eleven arrests, including that of Mrs Pethick-Lawrence and gave impetus to the movement. -

The Battle of Equality Contents 1

The Battle Of Equality Contents 1. Contents 2. Women’s Rights 3. 10 Famous women who made women’s suffrage happen. 4. Suffragettes 5. Suffragists 6. Who didn’t want women’s suffrage 7. Time Line of The Battle of Equality 8. Horse Derby 9. Pictures Woman’s Rights There were two groups that fought for woman's rights, the WSPU and the NUWSS. The NUWSS was set up by Millicent Fawcett. The WSPU was set up by Emmeline Pankhurst and her daughters. The WSPU was created because they didn’t want to wait for women’s rights by campaigning and holding petitions. They got bored so they created the WSPU. The WSPU went to the extreme lengths just to be heard. Whilst the NUWSS jus campaigned for women’s rights. 10 Famous women who made women’s suffrage happen. Emmeline Pankhurst (suffragette) - Leader of the suffragettes Christabel Pankhurst (suffragette)- Director of the most dangerous suffragette activities Constance Lytton (suffragette)- Daughter of viceroy Robert Bulwer-Lytton Emily Davison (suffragette)- Killed by kings horse Millicent Fawcett (suffragist)- Leader of the suffragist Edith Garrud (suffragette)- World professional Jiu-Jitsu master Silvia Pankhurst (suffragist)- Focused on campaigning and got expelled from the suffragettes by her sister Ethel Smyth (suffragette)- Conducted the suffragette anthem with a toothbrush Leonora Cohen (suffragette)- Smashed the display case for the Crown Jewels Constance Markievicz (suffragist)- Played a prominent role in ensuring Winston Churchill was defeated in elections Suffragettes The suffragettes were a group of women who wanted to vote. They did dangerous things like setting off bombs. The suffragettes were actually called The Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU). -

Congressional Record-Senate. Decemb~R 8

196 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-SENATE. DECEMB~R 8, gress hold no session for legislative purposes on Sunday-to the Com Mr. II.A.LE presented a petition of the Master Builders' Exchange mittee on the Judiciary. of Philadelphia, Pa., praying for a more careful investigation by the By Mr. O'NEILL, of Pennsylvania: Resolutions of the Tobacco Census Office of the electrical industries; which was referred :to the Trade Association of Philadelphia, requesting Congress to provide by Committee on the Census. legislation for the payment of a rebate of 2 cents per pound on the Ile also presenteda resolution adopted by the ChamberofCommerce stock of tax-paid tobacco and snuff on hand on the 1st of January, of New Haven, Conn., favoring the petition of the National Electric 1891-to the Committee on Ways and Means. Light Association, praying for a more careful investigation by the Cen By Mr. PETERS: Petition of Wichita wholesale grocers and numer sus Office of the electrical industries; which wus referred to the Com ous citizens of Kansa8, for rebate amendment to tariff bill-to the mittee on the Census. Committee on Ways and Means. l\Ir. GORMAN. I present a great number of memorials signed by By Mr. THOMAS: Petition ofW. Grams,W. J. Keller.and 9others, very many residents of the United States, remonstrating against the of La Crosse, ·wis., and B. T. Ilacon and 7 others, of the State of Minne passage of the Federal election bill now pending, or any other bill of sota, praying for the passage of an act or rebate amendment to the like purport, wb~ch the memoriali5ts think would tend to destroy the tariff law approved October 1, 1890, allowing certain drawbacks or re purity of elections, and would unnecessarily impose heavy burdens bates upon unbroken packages of smoking and manufactured tobacco on the taxpayers, and be revolutionizing the constitutional practices and snuffs-to the Committee on Ways and Means. -

Suffragette City: How Did the 'Votes for Women' Campaign Affect London

Suffragette City: How did the ‘votes for women’ campaign affect London 1906–1914? The UK campaign for women’s right to vote in parliamentary elections began in the mid-19th century. Campaigners used argument and debate to try to persuade the government. When this did not work by the beginning of the 20th century, new tactics were adopted. In 1903, the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) was set up in Manchester. The WSPU aimed to adopt more militant (strong or more direct) tactics to win the vote. Their members later became known as Suffragettes. When the WSPU moved to London in 1906, the movement’s emphasis altered. From 1906–1914 the fight to win the vote became a public, and sometimes violent struggle that was very visible on the streets of the capital. Why did the campaign move to London in 1906? Moving the campaign to the streets of London made the WSPU more visible. It also meant they could hold major events that attracted lots of people and publicity. This paper napkin is printed with a programme for Women’s Sunday on 21 June 1908. This was the first big event organised by the WSPU. The centre of the napkin shows the route of the seven marches through London meeting in Hyde Park. Around the centre are portraits of the main speakers and the Suffragette leaders. Souvenir paper table napkin Napkins like this were produced for all large public events from Women’s Sunday, 1908 in London from the early- to mid-20th century. They would have been sold for about one penny by street traders lining the route of the event. -

Orpheu Et Al. Modernism, Women, and the War

Orpheu et al. Modernism, Women, and the War M. Irene Ramalho-Santos* Keywords Little magazines, Poetry, Modernism, The Great War, Society, Sexual mores. Abstract The article takes off from Orpheu, the little magazine at the origin of Portuguese modernism, to reflect, from a comparative perspective, on the development of modernist poetry in the context of the Great War and the social changes evolving during the first decades of the twentieth century on both sides of the Atlantic. Palavras-chave “Little magazines,” Poesia, Modernismo, A Grande Guerra, Sociedade, Costumes sexuais. Resumo O artigo parte de Orpheu, a revista que dá origem ao modernismo português, para reflectir, numa perspectiva comparada, soBre o desenvolvimento da poesia modernista no contexto da Grande Guerra e das mudanças sociais emergentes nas primeiras décadas do século XX dos dois lados do Atlântico. * Universidade de CoimBra; University of Wisconsin-Madison. Ramalho Santos Orpheu et al. It is frequently repeated in the relevant scholarship that Western literary and artistic modernism started in little magazines.1 The useful online Modernist Journals Project (Brown University / Tulsa University), dealing so far only with American and British magazines, uses as its epigraph the much quoted phrase: “modernism began in the magazines”, see SCHOLES and WULFMAN (2010) and BROOKER and THACKER (2009-2013). With two issues published in 1915 and a third one stopped that same year in the galley proofs for lack of funding, the Portuguese little magazine Orpheu inaugurated modernism in Portugal pretty much at the same time as all the other major little magazines in Europe and the United States. This is interesting, given the proverbial belatedness of Portuguese accomplishments, and no less interesting the fact that, like everywhere else, Orpheu was followed, in Portugal as well, By a number of other little magazines. -

Communal Formations: Development of Gendered Identities

COMMUNAL FORMATIONS: DEVELOPMENT OF GENDERED IDENTITIES IN EARLY TWENTIETH-CENTURY WOMEN’ S PERIODICALS A Dissertation by by EMILY ANNE JANDA MONTEIRO Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved by: Chair of Committee, Katherine Kelly Committee Members, Marian Eide Claudia Nelson Cynthia Bouton Head of Department, Nancy Warren May 2013 Major Subject: English Copyright 2013 Emily Anne Janda Monteiro ABSTRACT Women’s periodicals at the start of the twentieth-century were not just recorders but also producers of social and cultural change. They can be considered to both represent and construct gender codes, offering readers constantly evolving communal identities. This dissertation asserts that the periodical genre is a valuable resource in the investigation of communal identity formation and seeks to reclaim for historians of British modernist feminism a neglected publication format of the early twentieth century. I explore the discursive space of three unique women’s periodicals, Bean na hÉireann, the Freewoman, and Indian Ladies Magazine, and argue that these publications exemplify the importance of the early twentieth-century British woman’s magazine-format periodical as a primary vehicle for the communication of feminist opinions. In order to interrogate how the dynamic nature of each periodical is reflected and reinforced in each issue, I rely upon a tradition of critical discourse analysis that evaluates the meaning created within and between printed columns, news articles, serial fiction, poetry, and short sketches within each publication. These items are found to be both representative of a similar value of open and frank discourse on all matters of gender subordination at that time and yet unique to each community of readers, contributors and editors.