The Concepts of Truth and Meaning in the Buddhist Scriptures, by Jose I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Religious Movements –Jainism and Buddhism 5.1 Timeline 5.2 Glossary

Religious Movements –Jainism and Buddhism 5.1 Timeline Timelines Image Description C 6th Century BCE Urbanization in the Ganges Plain C 6th Century BCE Formation of the earliest states C 6th Century BCE The rise of Magadha 563 BCE Birth of Gautama Buddha 540 BCE Birth of Mahavira 512 BCE Second Jaina Council held at Vallabhi 483 BCE Mahaparinirvana of Buddha 483 BCE First Buddhist Council held at Rajagriha 468 BCE Nirvana of Mahavira 383 BCE Second Buddhist Council held at Vaisali 250 BCE Third Buddhist Council held at Pataliputra 5.2 Glossary Staring Related Term Definition Character Term A Ahimsa Non-violence, Non-injury B Bikkhu Pali [Sanskrit bhikshu] a Buddhist monk D Digambara Literally ‘Sky-Clad’ – one of the Jaina schools H Hinayana Literally ‘lesser vehicle’, school of Buddhism K Karma Action or Deed M Mahayana Literally ‘Great vehicle’ –school of Buddhism M Moksha Liberation from rebirth N Nirvana Release from the cycle of rebirth P Pali An Indo-Aryan language S Sangha Frequently used to indicate the organizational order in Buddhism S Svetambara Literally ‘clad in white’ – one of the Jaina schools T Tirthankara Literally ‘monk ‘Ford builder’ – Jaina saint T Triratna Literally ‘three gems’, - In Jainism refers to the triple path of right faith, knowledge and conduct U Upasaka A male lay follower of the Buddha’s teaching U Upasika A female lay follower of the Buddha’s teaching 5.3 Web links Web links http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indian_religions http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jainism http://www.yourarticlelibrary.com/history/the-sixth-century-bc-was-a-period-of-religious-and-economic- unrest-in-india-history/4436/ http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Varna_%28Hinduism%29 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tirthankara http://www.dhammaweb.net/books/DVEMATIK.PDF 5.4 Bibliography Bibliography Basham, A.L., The History and doctrine of the Ajivikas, London, 1951, 2003 Basham, A.L., The wonder that was India, 3rd edn, Newyork, 1971 Battacharya. -

THE BUDDHIST SCRIPTURES COMPARED with the BIBLE! !Robert Krueger! Presented To! !SYMPOSIUM: the UNIQUENESS of the CHRISTIAN SCRIPTURES! Dr

!THE BUDDHIST SCRIPTURES COMPARED WITH THE BIBLE! !Robert Krueger! Presented to! !SYMPOSIUM: THE UNIQUENESS OF THE CHRISTIAN SCRIPTURES! Dr. Martin Luther College! New Ulm, MN! !April 15-17, 1993! !THE BUDDHIST SCRIPTURES COMPARED WITH THE BIBLE! !Introduction! In regard to the title of this essay and the theme of the symposium, both of which refer to scrip- tures, it must be noted that there's a lot more material to be found on Buddhism than on Buddhist scriptures -- at least it's easier to find. Whole books as well as parts of books dealing with Bud- dhism often treat the matter of Buddhist scriptures only briefly or in passing. To be sure, there are Buddhist scriptures and reference is made to a Buddhist canon, but as we shall see, these are dif- !ferent than and not so clearly defined as are our Christian Scriptures and the Biblical canon.! An appreciation for the Bible may also be gained by just looking at the origin, history, and doctrine of Buddhism, and these areas are also important in considering the Buddhist scriptures. Thus we'll !first look at those aspects of Buddhism as well as at some important terms and concepts.! !1. History and Origin of Buddhism! The founder of Buddhism is Siddhartha Gautama (ca. 560-480 B.C.), a prince of the Sakyas, who became known as Sakyamuni, sage of the Sakya people, and as the Buddha, the Enlightened One. There are various stories about his birth and life and even his conception, but it is generally agreed that he grew up as a prince and a member of a privileged class, married, and had a son. -

He Noble Path

HE NOBLE PATH THE NOBLE PATH TREASURES OF BUDDHISM AT THE CHESTER BEATTY LIBRARY AND GALLERY OF ORIENTAL ART DUBLIN, IRELAND MARCH 1991 Published by the Trustees of the Chester Beatty Library and Gallery of Oriental Art, Dublin. 1991 ISBN:0 9517380 0 3 Printed in Ireland by The Criterion Press Photographic Credits: Pieterse Davison International Ltd: Cat. Nos. 5, 9, 12, 16, 17, 18, 21, 22, 25, 26, 27, 29, 32, 36, 37, 43 (cover), 46, 50, 54, 58, 59, 63, 64, 65, 70, 72, 75, 78. Courtesy of the National Museum of Ireland: Cat. Nos. 1, 2 (cover), 52, 81, 83. Front cover reproduced by kind permission of the National Museum of Ireland © Back cover reproduced by courtesy of the Trustees of the Chester Beatty Library © Copyright © Trustees of the Chester Beatty Library and Gallery of Oriental Art, Dublin. Chester Beatty Library 10002780 10002780 Contents Introduction Page 1-3 Buddhism in Burma and Thailand Essay 4 Burma Cat. Nos. 1-14 Cases A B C D 5 - 11 Thailand Cat. Nos. 15 - 18 Case E 12 - 14 Buddhism in China Essay 15 China Cat. Nos. 19-27 Cases F G H I 16 - 19 Buddhism in Tibet and Mongolia Essay 20 Tibet Cat. Nos. 28 - 57 Cases J K L 21 - 30 Mongolia Cat. No. 58 Case L 30 Buddhism in Japan Essay 31 Japan Cat. Nos. 59 - 79 Cases M N O P Q 32 - 39 India Cat. Nos. 80 - 83 Case R 40 Glossary 41 - 48 Suggestions for Further Reading 49 Map 50 ■ '-ie?;- ' . , ^ . h ':'m' ':4^n *r-,:«.ria-,'.:: M.,, i Acknowledgments Much credit for this exhibition goes to the Far Eastern and Japanese Curators at the Chester Beatty Library, who selected the exhibits and collaborated in the design and mounting of the exhibition, and who wrote the text and entries for the catalogue. -

Vasubandhu's) Commentary on His "Twenty Stanzas" with Appended Glossary of Technical Terms

AN INTRODUCTION AND TRANSLATION OF VINITADEVA'S EXPLANATION OF THE FIRST TEN VERSES OF (VASUBANDHU'S) COMMENTARY ON HIS "TWENTY STANZAS" WITH APPENDED GLOSSARY OF TECHNICAL TERMS Gregory Alexander Hillis Palo Alto, California B.A., University of California, Santa Cruz, 1979 A Thesis Presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of Religious Studies University of Virginia May, 1993 ABSTRACT In this thesis I argue that Vasubandhu categorically rejects the position that objects exist external to the mind. To support this interpretation, I engage in a close reading of Vasubandhu's Twenty Stanzas (Vif!lsatika, nyi shu pa), his autocommentary (vif!lsatika- vrtti, nyi shu pa'i 'grel pa), and Vinrtadeva's sub-commentary (prakaraiJa-vif!liaka-f'ika, rab tu byed pa nyi shu pa' i 'grel bshad). I endeavor to show how unambiguous statements in Vasubandhu's root text and autocommentary refuting the existence of external objects are further supported by Vinitadeva's explanantion. I examine two major streams of recent non-traditional scholarship on this topic, one that interprets Vasubandhu to be a realist, and one that interprets him to be an idealist. I argue strenuously against the former position, citing what I consider to be the questionable methodology of reading the thought of later thinkers such as Dignaga and Dharmak:Irti into the works of Vasubandhu, and argue in favor of the latter position with the stipulation that Vasubandhu does accept a plurality of separate minds, and he does not assert the existence of an Absolute Mind. -

Buddhist Backgrounds of the Burmese Revolution Buddhist Backgrounds Ofthe Burmese Revolution

BUDDHIST BACKGROUNDS OF THE BURMESE REVOLUTION BUDDHIST BACKGROUNDS OFTHE BURMESE REVOLUTION by E. SARKISYANZ PH.D. apl. Professor Freiburg University PREFACE BY DR. PAUL MUS Professor at the College de France and Yale University • Springer-Science+Business Media, B.Y. I965 Dedicated to the memory 01 my unlorgettable teacher ARNOLD BERGSTRAESSER ISBN 978-94-017-5830-7 ISBN 978-94-017-6283-0 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-94-017-6283-0 Copyright I965 by Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht All rights reserved, including the right to translate or to reproduce this book or parts thereof in any form Originally published by Martinus Nijhoff in 1965. Softcover reprint ofthe hardcover 1st edition 1965 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface by PAUL Mus. VII Foreword ..... XXIII Abbreviations . XXVII I. The Buddhist tradition of Burma's history . I 11. Buddhist traditions about a perfect society, its decline and the origin of the state . .. 10 III. Republican institutions in pre-Buddhist India and in the Buddhist order. .. 17 IV. The Buddhist welfare state of Ashoka. .. 26 v. Survival of Ashokan social and political traditions in Theravada kingship . .. 33 VI. On the problem of social ethics of Theravada Buddhism 37 VII. Emergence of the Bodhisattva ideal of kingship in Theravada Buddhism . .. 43 VIII. Pre-Buddhist fertility elements of the charisma of Burmese kingship . .. 49 IX. Economic implications of the Buddhist ideal of kingship 54 x. The Bodhisattva ideal of Burmese kingship . .. 59 XI. Kamma and Buddhist merit-causality as rationale for medieval Burma's social order . .. 68 XII. Buddhist ethics against the pragmatism of power under the Burmese kings. -

Getting to Know the Four Schools of Tibetan Buddhism

THE FOUR ORDERS: BOOK EXCERPT Getting to know the Four Schools of Tibetan Buddhism hundreds ofyears that the four main been codified by Tibetan intellectual historians, who categorize Buddha's teachings in terms of three distinct of Tibetan Buddhism — Nyingma, vehicles — the Lesser Vehicle (Hinayana), the Great Vehicle akya, and Gelug — have evolved out of (Mahayana), and the Vajra Vehicle (Vajrayana) — each of which was intended to appeal to the spiritual capacities of their common roots in India, a wide array of particular groups. divergent practices, beliefs, and rituals have • Hinayana was presented to people intent on personal salvation in which one transcends come into being. However, there are signifi- suffering and is liberated from cyclic existence. • The audience of Mahayana teachings included cant underlying commonalities between the trainees with the capacity to feel compassion for different traditions, such as the importance the sufferings of others who wished to seek awakening in order to help sentient beings over- of overcoming attachment to the phenomena come their sufferings. of cyclic existence, and the idea that it is • Vajrayana practitioners had a strong interest in the welfare of others, coupled with determination necessary for trainees to develop an attitude to attain awakening as quickly as possible, and the spiritual capacity to pursue the difficult practices of sincere renunciation. John Powers' fasci- of tantra. nating and comprehensive book, Introduction Indian Buddhism is also commonly divided by scholars of the four Tibetan orders into four main schools of tenets to Buddhism, re-issued by Snow Lion in — Great Exposition School, Sutra School, Mind Only School, September 2007, contains a lucid explanation and Middle Way School. -

Tibetan Vajrayana Buddhist Preliminaries Practices 3 Levels Of

Tibetan Vajrayana Buddhist Preliminaries Practices 3 Levels of Buddhism 1/ Hinayana (Meditation and liberation for Self enlightenment) 2/ Mahayana (Bodhisattva Mind and liberation to be able to liberate others) 3/ Vajrayana or Tantrayana (Non Duality Emptiness, All Phenomenon are Nirvana, Guru Yoga and Yidam visualisation, Mahamoudra meditation and liberation in one's life) 3 Refuges Taking refuge in the 3 Jewels is a ceremony or a self decision that marks officially the entrance in Buddhism, and when somebody wants to call himself or herself a Buddhist. Taking refuge in the 3 Jewels is the first step in Buddhism. Taking refuge in the 3 Jewels consists in repeating 3 times the phrases "I take refuge in the ..." with and for each jewel. Buddha (Doctor) Dharma (Medicine) Sangha (Nurse) 5 Precepts Engaging oneself in the 5 precepts is an important part of the Buddhist practice as it means that the person is trying to bring the Dharma into her or his own life and daily reality. It is a real engagement and a real daily effort to live with the guidelines of the Dharma, with integrity and compassion, and to follow the 5 precepts. Such a conscious and volontary engagement is also very helpful and meaningful in order to bring more understanding and experiences in one's own practice. Tibetan Vajrayana Buddhist Preliminaries Practices 1 - 17 The 5 precepts is about avoiding wrong actions and developping skillful actions. Undertaking the training to abstain from doing unskilful or negative actions. Avoiding 10 evil actions and developing 10 virtuous actions. The 5 precepts are based on non violence (in body, speech and mind, and about others living beings, material objects, and self) upon others and oneself. -

Under Memberships

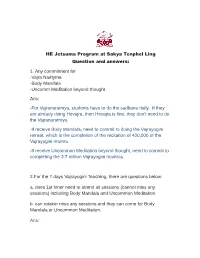

HE Jetsuma Program at Sakya Tenphel Ling Question and answers: 1. Any commitment for -Vajra Nairtyma -Body Mandala -Uncomm Meditation beyond thought Ans: -For Vajranaratmya, students have to do the sadhana daily. If they are already doing Hevajra, then Hevajra is fine, they don’t need to do the Vajranaratmya. -If receive Body Mandala, need to commit to doing the Vajrayogini retreat, which is the completion of the recitation of 400,000 of the Vajrayogini mantra. -If receive Uncommon Meditation beyond thought, need to commit to completing the 3.7 million Vajrayogini mantras. 2.For the 7 days Vajrayogini Teaching, there are questions below: a. does 1st timer need to attend all sessions (cannot miss any sessions) including Body Mandala and Uncommon Meditation. b. can retaker miss any sessions.and they can come for Body Mandala or Uncommon Meditation. Ans: a. Students who want to receive the proper transmission should attend all the sessions. However, if they don’t wish to receive the commitments of retreat and mantra accumulation (3.7 million), as is required if receive the body mandala and uncommon meditation beyond thought, they can skip those relevant sessions. b. For old timers who received the entire set before, it is their choice. However, Jetsun Kushok thinks it is beneficial to receive the teachings in its entirety without selectively choosing and skipping. 3.a For those new ones who.has taken 2 days Vajra Nairatyma empowerment, can they continue to take Vajrayogini Chin Lab and then go to the 7 days teaching? b. For those who.have taken 2 days Hevajra cause empowerment, they can come for Vajra Nairatyma empowerment and no need be one of the 25 new takers. -

Shankara: a Hindu Revivalist Or a Crypto-Buddhist?

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Religious Studies Theses Department of Religious Studies 12-4-2006 Shankara: A Hindu Revivalist or a Crypto-Buddhist? Kencho Tenzin Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/rs_theses Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Tenzin, Kencho, "Shankara: A Hindu Revivalist or a Crypto-Buddhist?." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2006. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/rs_theses/4 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Religious Studies at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Religious Studies Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SHANKARA: A HINDU REVIVALIST OR A CRYPTO BUDDHIST? by KENCHO TENZIN Under The Direction of Kathryn McClymond ABSTRACT Shankara, the great Indian thinker, was known as the accurate expounder of the Upanishads. He is seen as a towering figure in the history of Indian philosophy and is credited with restoring the teachings of the Vedas to their pristine form. However, there are others who do not see such contributions from Shankara. They criticize his philosophy by calling it “crypto-Buddhism.” It is his unique philosophy of Advaita Vedanta that puts him at odds with other Hindu orthodox schools. Ironically, he is also criticized by Buddhists as a “born enemy of Buddhism” due to his relentless attacks on their tradition. This thesis, therefore, probes the question of how Shankara should best be regarded, “a Hindu Revivalist or a Crypto-Buddhist?” To address this question, this thesis reviews the historical setting for Shakara’s work, the state of Indian philosophy as a dynamic conversation involving Hindu and Buddhist thinkers, and finally Shankara’s intellectual genealogy. -

The Hinayana Fallacy

e Hīnayāna Fallacy* Anālayo In what follows I examine the function of the term Hīnayāna as a referent to an institutional entity in the academic study of the history of Buddhism. I begin by surveying the use of the term by Chinese pilgrims travelling in India, followed by taking up to the Tarkajvālā’s depiction of the controversy between adherents of the Hīnayāna and the Mahāyāna. I then turn to the use of the term in the West, in particular its promotion by the Japanese del- egates at the World’s Parliament of Religions in Chicago in . I conclude that the current academic use of the term as a referent to a Buddhist school or Buddhist schools is misleading. e Chinese Pilgrims According to the succinct definition given in the Encyclopedia of Buddhism, Hīna- yāna “is a pejorative term meaning ‘Lesser Vehicle’. Some adherents of the ‘Greater Vehicle’ (Mahāyāna) applied it to non-Mahāyānist schools such as the eravāda, the Sarvāstivāda, the Mahāsāmghika,. and some fieen other schools.” * I am indebted to Max Deeg, Sāmanerī. Dhammadinnā, Shi Kongmu, Lambert Schmithausen, Jonathan Silk, Peter Skilling, and Judith Snodgrass for comments on a dra version of this paper. Strong : , who continues by indicating that in the Encyclopedia of Buddhism the term “mainstream Buddhist schools” is used instead. is term, which is an improvement over Hīna- yāna, has not found unanimous acceptance, cf., e.g., Sasaki : note : “I cannot, however, subscribe to the indiscreet use of the term ‘Mainstream’, which implies a positive assertion about a particular historical situation, and therefore, although completely outmoded, I continue to use the terms ‘Mahāyāna’ and ‘Hīnayāna’”; for critical comments on the expression “mainstream” cf. -

The Compass of Zen by Zen Master Seung Sahn

I N D E X to The Compass of Zen by Zen Master Seung Sahn John Holland Ty Koontz The Kwan Um School of Zen 2016 Foreword Zen Master Seung Sahn tells many good stories in his book, including how he shocked a group of French priests in explaining primary point to them and how nuns from the Eastern temple and the Western temple vied to impress Zen Master Hak Un with their pronunciations of Kwan Seum Bosal. When I prepare a dharma talk, the question for me has always been, where in The Compass of Zen are the stories discussed? The work desperately needed an index. Experience told me it would be a difficult task, and I turned for help to Ty Koontz. I had admired the index Ty made for Zen Master Wu Kwang’s (Richard Shrobe) book Elegant Failure: A Guide to Zen Koans and was delighted that Ty agreed to help me. Because we have attempted to do justice to DSSN’s teaching, for which we are all so grateful, this index is long. The ideal index does not exist. All an indexer can do is to make the best possible index he or she can. That means following one’s intuition and general knowledge. One of the most challenging aspects of making an index for The Compass of Zen is the way in which everything is interrelated. Cross-references are needed to help the reader find related concepts while avoiding an enormous snarled spider-web of relationships. Main headings for concepts like attainment, emptiness, meditation, mind, practice, suffering, thinking, and truth are necessary, but these concepts relate to so much of the book that subentries could easily overwhelm the index. -

English Books

Shelf No. Title Author Publisher Date Notes DIS/A 001.01 Seven steps to nibbana Abeyesereka, Solomon DIS/A 002.01 Down to earth: A Handbook for Abhinyana MJSB the sceptical DIS/A 002.02 Let me see Abhinyana 1990 DIS/A 003.01 Life of Buddha Albers, A. Christina The Corporate Body of the Buddha Educational Foundation DIS/A 004.01 Kings of Buddha's time Amritananda, Dr. Bhikkhu Ananda Kuti Vihara 1983 Trust DIS/A 005.01 Dying to live (the role of kamma in Aggacitta Bhikkhu Sukhi Hotu Dhamma 1999 dying & rebirth) Publications DIS/A 006.01 The Buddha & his dhamma Ambedkar, B.R. Dr. Buddha Bhoomi 1997 Publication DIS/A 007.01 Buddhism lectures and essays Ven Balangoda Samayawardhana 1993 Anandamaitreya DIS/A 008.01 Sir Edwin Arnold's light of Asia Sir Edwin Arnold with M.D. Gunasena an introductory essay by Dr Malasekera DIS/A 009.01 Atisha: a biography of the renowned Translated from Tibetan Mahayana Publications 1984 Buddhist sage sources by Lama Thubten Kalsang et al DIS/A 010.01 That the true Dhamma might last Readings selected by W.A.V.E. a long time King Asoka/ translated by Thanissaro Bhikkhu DIS/A 011.01 Practising the Dhamma with a View to Abeysekera, Radhika Buddha Educational 2002 Nibbana Foundation DIS/A 012.01 The Bhikkhus' Rules: A Guide for Ariyesako, Bhikkhu W.A.V.E. 1998 2 copies Laypeople DIS/B 001.01 Happiness and hunger Acariya Buddhadasa (From a talk given 7 May 1986 at Suan Mokkh) DIS/B 001.02 Food for thought 精神食糧 :Some Buddhadasa Bhikkhu 香光 1996 中英對照 teachings of Buddhadasa Bhikkhu 佛使比丘 DIS/B 001.03 Two kinds of language Buddhadasa Bhikkhu DIS/B 001.04 The Danger of "I" Buddhadasa Bhikkhu BMS Publication 1974 Shelf No.