Appendix Ii: 'Carriers', Essay in Radiosonic Glitch

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Connecting Time and Timbre Computational Methods for Generative Rhythmic Loops Insymbolic and Signal Domainspdfauthor

Connecting Time and Timbre: Computational Methods for Generative Rhythmic Loops in Symbolic and Signal Domains Cárthach Ó Nuanáin TESI DOCTORAL UPF / 2017 Thesis Director: Dr. Sergi Jordà Music Technology Group Dept. of Information and Communication Technologies Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Barcelona, Spain Dissertation submitted to the Department of Information and Communication Tech- nologies of Universitat Pompeu Fabra in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR PER LA UNIVERSITAT POMPEU FABRA Copyright c 2017 by Cárthach Ó Nuanáin Licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 Music Technology Group (http://mtg.upf.edu), Department of Information and Communication Tech- nologies (http://www.upf.edu/dtic), Universitat Pompeu Fabra (http://www.upf.edu), Barcelona, Spain. III Do mo mháthair, Marian. V This thesis was conducted carried out at the Music Technology Group (MTG) of Universitat Pompeu Fabra in Barcelona, Spain, from Oct. 2013 to Nov. 2017. It was supervised by Dr. Sergi Jordà and Mr. Perfecto Herrera. Work in several parts of this thesis was carried out in collaboration with the GiantSteps team at the Music Technology Group in UPF as well as other members of the project consortium. Our work has been gratefully supported by the Department of Information and Com- munication Technologies (DTIC) PhD fellowship (2013-17), Universitat Pompeu Fabra, and the European Research Council under the European Union’s Seventh Framework Program, as part of the GiantSteps project ((FP7-ICT-2013-10 Grant agreement no. 610591). Acknowledgments First and foremost I wish to thank my advisors and mentors Sergi Jordà and Perfecto Herrera. Thanks to Sergi for meeting me in Belfast many moons ago and bringing me to Barcelona. -

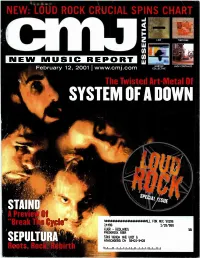

System of a Down Molds Metal Like Silly Putty, Bending and Shaping Its Parame- 12 Slayer's First Amendment Ters to Fit the Band's Twisted Vision

NEW: LOUD ROCK CRUCIAL SPINS CHART LOW TORTOISE 1111 NEW MUSIC REPORT Uà NORTEC JACK COSTANZO February 12, 20011 www.cmj.com COLLECTIVE The Twisted Art-Metal Of SYSTEM OF ADOWN 444****************444WALL FOR ADC 90138 24438 2/28/388 KUOR - REDLAHDS FREDERICK SUER S2V3HOD AUE unr G ATASCADER0 CA 88422-3428 IIii II i ti iii it iii titi, III IlitlIlli lilt ti It III ti ER THEIR SELF TITLED DEBUT AT RADIO NOW • FOR COLLEGE CONTACT PHIL KASO: [email protected] 212-274-7544 FOR METAL CONTACT JEN MEULA: [email protected] 212-274-7545 Management: Bryan Coleman for Union Entertainment Produced & Mixed by Bob Marlette Production & Engineering of bass and drum tracks by Bill Kennedy a OADRUNNEll ACME MCCOWN« ROADRUNNER www.downermusic.com www.roadrunnerrecords.com 0 2001 Roadrunner Records. Inc. " " " • Issue 701 • Vol 66 • No 7 FEATURES 8 Bucking The System member, the band is out to prove it still has Citing Jane's Addiction as a primary influ- the juice with its new release, Nation. ence, System Of A Down molds metal like Silly Putty, bending and shaping its parame- 12 Slayer's First Amendment ters to fit the band's twisted vision. Loud Follies Rock Editor Amy Sciarretto taps SOAD for Free speech is fodder for the courts once the scoop on its upcoming summer release. again. This time the principals involved are a headbanger institution and the parents of 10 It Takes A Nation daughter who was brutally murdered by three Some question whether Sepultura will ever of its supposed fans. be same without larger-than-life frontman 15 CM/A: Staincl Max Cavalera. -

12, 13, 14 Maig

, , SALA D EXPOSICIONS DOMENEC FITA , INSTAL.LACIO PERMANENT , , S ha acabat el brOquil , El videojoc d Electrotoylets (INSTAL·LACIÓ INTERACTIVA) 12, 13, 14 maig casa de cultura de, girona v mostra de mUsica experimental de girona www.remor.cat Electrotoylets es caracteritza per portar el repertori tradicional català al terreny de l’electrònica, l’experimentació i el sentit de l’humor. Després de triomfar en escenaris de la Xina, Holanda, França, el Regne Unit i festivals com el Sònar, Temporada Alta o Organitza Entrada lliure Etnival, el grup ha fet un pas endavant realment innovador: crear Casa de Cultura de Girona Aforament limitat el seu propi videojoc. S’ha acabat el bròquil és un ambiciós projecte Direcció artística desenvolupat per un equip multidisciplinar que es basa en la Nene Coca La Casa de Cultura es reserva el dret de modificar, per necessitats organitzatives, música i l’imaginari estètic del grup, mescla de píxel art amb les Producció executiva els horaris i els programes anunciats, i el icones tradicionals catalanes. Els protagonistes del videojoc són Produccions A. Paranoides d’anul·lar un concert per causes imprevistes. els mateixos membres del grup i l’acció està plagada de dimonis, Casa de Cultura de Girona caganers, porrons i botifarres, sempre amb la ironia com a bandera. Ajudant de producció El projecte es difon de forma gratuïta a través de la xarxa a la web Enric Masgrau www.electrotoylets.cat Direcció tècnica Jordi BruguEs, Amb la col·laboració del CoNCA i AGITA Imatge portada, disseny gràfic i web Xavi CasadesUs, Col·labora Discontinu Records dj 12 20:00h_Auditori Viader 21:30h_Auditori Viader 21:00h_AULA MAGNA (ORGUE / IMPROVISACIÓ) (OSCIL·LADORS FABRICATS I RÀDIO AM MODIFICADA) i també en diverses compilacions. -

“Knowing Is Seeing”: the Digital Audio Workstation and the Visualization of Sound

“KNOWING IS SEEING”: THE DIGITAL AUDIO WORKSTATION AND THE VISUALIZATION OF SOUND IAN MACCHIUSI A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAM IN MUSIC YORK UNIVERSITY TORONTO, ONTARIO September 2017 © Ian Macchiusi, 2017 ii Abstract The computer’s visual representation of sound has revolutionized the creation of music through the interface of the Digital Audio Workstation software (DAW). With the rise of DAW- based composition in popular music styles, many artists’ sole experience of musical creation is through the computer screen. I assert that the particular sonic visualizations of the DAW propagate certain assumptions about music, influencing aesthetics and adding new visually- based parameters to the creative process. I believe many of these new parameters are greatly indebted to the visual structures, interactional dictates and standardizations (such as the office metaphor depicted by operating systems such as Apple’s OS and Microsoft’s Windows) of the Graphical User Interface (GUI). Whether manipulating text, video or audio, a user’s interaction with the GUI is usually structured in the same manner—clicking on windows, icons and menus with a mouse-driven cursor. Focussing on the dialogs from the Reddit communities of Making hip-hop and EDM production, DAW user manuals, as well as interface design guidebooks, this dissertation will address the ways these visualizations and methods of working affect the workflow, composition style and musical conceptions of DAW-based producers. iii Dedication To Ba, Dadas and Mary, for all your love and support. iv Table of Contents Abstract .................................................................................................................. -

Mochipetmochipet

MochipetMochipet rawrrawr meansmeans i You! Born in Taiwan R.O.C. to Rocket Scientist father and Kindergarten Teacher mother, David Wang (a.k.a. Mochipet) has been tinkering with electronics since he was a child. However, not until he added music to the equation, did something special begin to take shape. Having grown up listening to metal guitar, avant-garde jazz, and mainstream hip-hop, David’s eclectic taste can now be seen in his music – ever changing, and always evolving. His fervency for diversity can also be noted in the mixed bag of his many artist collaborations which include the likes of legendary skateboarder Ray Barbee (Powell Peralta), Techo producer Ellen Allien (Berlin), hip-hop MCs Mikah9 (Freestyle Fellowship), Casual (Hieroglyphics), and Raashan Ahmad (Crown City Rockers), electro Miami gangster Otto Von Schirach , booty bass rockstars 215 The Freshest Kids and Spank Rock (BigDada), mashup glitch tweeker Kid606 (Tigerbeat6), Edwardian suit-wearing Daedelus (Ninjatune), glitch popstars Jahcoozi (Kitty-Yo), and avant-garde jazz legend Weasel Walter (Flying Luttenbach- ers). David has also shared the stage with a myriad of influential music pioneers, including Aaron Spectre, Andrea Parker, Autechre, Bassnectar, Boom Bip, Bucovina Club, Cargo Natty, Carl Craig, Chris Clark, CLP, Cristian Vogal, Daedelus, Dat Politics, Devlin & Darko, DJ DJ Plasticman, Qbert, DJ Spooky, Drop the Lime, Ellen Allien, Felix Da Housecat, Fluokids, Flying Lotus, Ghislain Poirier, Gift of Gab, Glitchmob, Jahcoozi, Juan Maclean, Ken Ishii, Kid606, Kid Koala, Lazersword, Luke Vibert, Mary Ann Hobbs, Meat Beat Manifesto, Matmos, M.I.A, Mikah 9, Modeselektor, Otto Von Schirach, Skream, Superpitcher, The Bug, Tittsworth, and Tussle, to name a select few. -

Downloaded Directly, Or Burned to Optical Media Emerged in the 1970S

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Interactive Time Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/8kg6q723 Author Moran, Chuktropolis Welling Publication Date 2013 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Interactive Time A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Communication by Chuktropolis Welling Moran Committee in charge: Professor Brian Goldfarb, Chair Professor Jordan Crandall Professor Nitin Govil Professor Chandra Mukerji Professor Stefan Tanaka 2013 xxx The Dissertation of Chuktropolis Welling Moran is approved and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: __________________________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________ Chair University of California, San Diego 2013 iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page ............................................................................................................... iii Table of Contents ......................................................................................................... iv List of Images .............................................................................................................. -

MTO 11.4: Garcia, on and On

Volume 11, Number 4, October 2005 Copyright © 2005 Society for Music Theory Luis-Manuel Garcia KEYWORDS: Electronic Dance Music, repetition, pleasure, listening ABSTRACT: Repetition has often been cast in a negative light, associated with immature or regressive states. This view is reflected in music criticism and pedagogy, recast in aesthetic terms and it also reappears in cultural criticism, attacking repetition as a dangerous tool for social control. Defenses that have been mounted in favor of repetition seem inadequate in that they tend to recategorize certain repetitive practices as not-quite-repetition, rather than defend repetition tout court. This article uses examples from Electronic Dance Music (EDM) to provide an alternate approach to repetition that focuses on the experience of pleasure instead of a static attribution of aesthetic or ethical value. In particular, this is explored through three concepts: repetition as process, repetition as prolongation of pleasure, and process itself as pleasurable. Underlying these concepts is a formulation of pleasure first coined as Funktionslust, or “function pleasure,” reconceived here as “process pleasure.” Received October 2005 [1] “I LIKE THE TUNE, BUT IT‘S SO REPETITIVE.”(1) [1.1] Why does this sentence make intuitive sense, even though the adjective “repetitive” has no modifier indicating a positive or negative evaluation? Much like adjectives such as “monotonous,” “boring,” and “unoriginal,” “repetitive” seems to come with a negative connotation built-in. Outside the realm of aesthetic criticism, however, repetitiveness can play seemingly positive roles. For example, it is central to memory formation as well as to redundant error-checking in data transfer protocols, and it plays a large role in pedagogy, childhood development, and pattern recognition in general.(2) This connection to childhood learning, however, has at times worked against repetition, associating it with childlike behavior, underdeveloped consciousness, and regression. -

Human Voice in Trap

Mumbling, Shouting, and Singing: Listening to the (Non)Human Voice in Trap Eline Langejan, 3970078 Utrecht University Department of Media and Culture Studies RMA Musicology Thesis Thesis supervisor: Dr. Michiel Kamp Second reader: Dr. Floris Schuiling Date of submission: 17 August 2020 Mumbling, Shouting, and Singing: Listening to the (Non)Human Voice in Trap | Eline Langejan, 3970078 Abstract Since the 1990s, trap has increasingly influenced mainstream popular music. The Southern-American genre is notorious for its “trap-beat” as well as a vocal style that is often derogatorily referred to as mumble-rap or mushmouth rap. This vocal style is characterized by the murmured lyrical delivery causing a high level of unintelligibility. Different from mainstream post-race hip hop—which Justin Burton classifies as clearly pronounced, politically engaged hip hop performed by artists such as Kendrick Lamar—trap lyricism rarely involves anything other than money, promiscuity, and excessive lifestyles. Moreover, typical trap music uses a fair amount of expressive exclamations and ad libs, for instance, the “choppa” sound: brrrah!, where the rattling r’s imitate the sound of an automatic firearm, adding to a violent and noisy sound experience for a mainstream audience that has become used to post-race hip hop (Burton 2017). The perceived sonic blackness (Eidsheim 2011) in trap, which is the perceived black body in sound, urges questions about the way in which the voice can be rendered less-than-human, or even nonhuman. The sonic palette of trap deliberately invites a listening experience of blackness by making use of the sonic color line, which refers to sounds that are racialized by the listening ear in the historic context of segregation, slavery, and othering (Stoever 2016). -

アーティスト 商品名 フォーマット 発売日 商品ページ 555 Solar Express CD 2013/11/13

【SOUL/CLUB/RAP】「怒涛のサプライズ ボヘミアの狂詩曲」対象リスト(アーティスト順) アーティスト 商品名 フォーマット 発売日 商品ページ 555 Solar Express CD 2013/11/13 https://tower.jp/item/3319657 1773 サウンド・ソウルステス(DIGI) CD 2010/6/2 https://tower.jp/item/2707224 1773 リターン・オブ・ザ・ニュー CD 2009/3/11 https://tower.jp/item/2525329 1773 Return Of The New (HITS PRICE) CD 2012/6/16 https://tower.jp/item/3102523 1773 RETURN OF THE NEW(LTD) CD 2013/12/25 https://tower.jp/item/3352923 2562 The New Today CD 2014/10/23 https://tower.jp/item/3729257 *Groovy workshop. Emotional Groovin' -Best Hits Mix- mixed by *Groovy workshop. CD 2017/12/13 https://tower.jp/item/4624195 100 Proof (Aged in Soul) エイジド・イン・ソウル CD 1970/11/30 https://tower.jp/item/244446 100X Posse Rare & Unreleased 1992 - 1995 Mixed by Nicky Butters CD 2009/7/18 https://tower.jp/item/2583028 13 & God Live In Japan [Limited] <初回生産限定盤>(LTD/ED) CD 2008/5/14 https://tower.jp/item/2404194 16FLIP P-VINE & Groove-Diggers Presents MIXCHAMBR : Selected & Mixed by 16FLIP <タワーレコード限定> CD 2015/7/4 https://tower.jp/item/3931525 2 Chainz Collegrove(INTL) CD 2016/4/1 https://tower.jp/item/4234390 2000 And One Voltt 02 CD 2010/2/27 https://tower.jp/item/2676223 2000 And One ヘリタージュ CD 2009/2/28 https://tower.jp/item/2535879 24-Carat Black Ghetto : Misfortune's Wealth(US/LP) Analog 2018/3/13 https://tower.jp/item/4579300 2Pac (Tupac Shakur) TUPAC VS DVD 2004/11/12 https://tower.jp/item/1602263 2Pac (Tupac Shakur) 2-PAC 4-EVER DVD 2006/9/2 https://tower.jp/item/2084155 2Pac (Tupac Shakur) Live at the house of blues(BRD) Blu-ray 2017/11/20 https://tower.jp/item/4644444 -

Arbiter, March 21 Students of Boise State University

Boise State University ScholarWorks Student Newspapers (UP 4.15) University Documents 3-21-2001 Arbiter, March 21 Students of Boise State University Although this file was scanned from the highest-quality microfilm held by Boise State University, it reveals the limitations of the source microfilm. It is possible to perform a text search of much of this material; however, there are sections where the source microfilm was too faint or unreadable to allow for text scanning. For assistance with this collection of student newspapers, please contact Special Collections and Archives at [email protected]. � _ _ __ __~____ .' .......... ~ ... ~__ .- _ '~_.. l. - • - - -. - SliAIGHT FROM SA11JRDAYNIGHT UVE! "GOATBOr'"JOE PESCI" and "HAll BAKED" JIJI DER Two~ows 1:50/9:30 "OneNight Only THE BIG EASY COMEDYCLUBSEmNG Tickets available at all TIcketweb outlets, Including Record Exchange, Boise Co-op, Newt & Harolds, Moonbeams In Meridian and The Music Exchange of Nampa, by calling 1-800·965-4827. or www.tlcketweb.com. Full bar with 10. All ages welcome. Tickets on sale at all Tlcketweb outlets. by calling 1-800-965-4827. and online at www.tlcketweb.com. Produced by Bravo Entertainment. ~rPE"! hpbusi.ne~s ~~ wtlI'fZIZrIwireless " .. , .' solutIons ~ WWW·,blflvobsp.ex>m,.. ------------ -" -~. __ ._-_._---~ _l= CarissaWolf Editor ASBSUPresident Nate Peterson says he can't represent 16,000 SeanHayes students but a survey can ... page 10 AssociateEditor WendyYoungblood Assignment Editor MikeWinter Arts and Entertainment Editor letters •. ;page4. DougDana Sports Editor editorial •.. page 4. History-in-Progress: A crash course in ' streetwlse ••• page 5., DavidCain women's history ... page 6 CopyEditor guest opinion ..• page6. -

Oval, the Glitch and the Utopian Politics of Noise

...TICK-TICK-TICK-TICK-TICK ... OVAL, THE GLITCH AND THE UTOPIAN POLITICS OF NOISE James Brady Cranfield-Rose B.A. (Honours), Simon Fraser University, 1999 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS In the School Of Communication O James Brady Cranfield-Rose 2004 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY July 2004 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author APPROVAL NAME: J. Brady Cranfield-Rose DEGREE: TITLE OF TICK-TICK-TICK-TICK-TICK THESIS: OVAL, THE GLITCH AND THE UTOPIAN POLITICS OF NOISE EXAMINING COMMITTEE: CHAIR: Prof. Gary McCarron -- Prof. Martin Laba Senior Supervisor. School of Communication, SFU Prof. Allyson Clay Supervisor-,School for the Contemporary Arts, SFU Prof. Richard Gruneau Examiner, School of Communication, SFU Date: Partial Copyright Licence The author, whose copyright is declared on the title page of this work, has granted to Simon Fraser University the right to lend this thesis, project or extended essay to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. The author has further agreed that permission for multiple copying of this work for scholarly purposes may be granted by either the author or the Dean of Graduate Studies. It is understood that copying or publication of this work for financial gain shall not be allowed without the author's written permission. -

“Black Rhythm,” “White Logic,” and Music Theory in the Twenty-First Century

Perchard, Tom. 2015. New Riffs on the Old Mind-Body Blues: “Black Rhythm,” “White Logic,” and Music Theory in the Twenty-First Century. Journal of the Society for American Music, 9(3), pp. 321-348. ISSN 1752-1963 [Article] https://research.gold.ac.uk/id/eprint/15057/ The version presented here may differ from the published, performed or presented work. Please go to the persistent GRO record above for more information. If you believe that any material held in the repository infringes copyright law, please contact the Repository Team at Goldsmiths, University of London via the following email address: [email protected]. The item will be removed from the repository while any claim is being investigated. For more information, please contact the GRO team: [email protected] New Riffs on the Old Mind-Body Blues: “Black Rhythm,” “White Logic,” and Music Theory in the 21st-Century Journal of the Society for American Music. 9/3 (2015). 321-348. Tom Perchard Abstract Contemporary music historians have shown how taxonomic divisions of humanity— constructed in earnest within European anthropologies and philosophies from the Enlightenment on—were reflected in 18th and 19th-century theories of musical-cultural evolution, with complex and intellectualized art music forms always shown as transcending base and bodily rhythm, just as light skin supposedly transcended dark. The errors of old and now disreputable scholarly approaches have been given much attention. Yet scientifically oriented 21st-century studies of putatively Afro-diasporic and, especially, African American rhythmic practices seem often to stumble over similarly racialized faultlines, the relationship between “sensory” music and its “intelligent” comprehension, and analysis still procedurally and politically fraught.