The Arcuate Nucleus of the Hindbrain Is a Displaced Part of the Inferior Olive

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Floor Plate and Netrin-1 Are Involved in the Migration and Survival of Inferior Olivary Neurons

The Journal of Neuroscience, June 1, 1999, 19(11):4407–4420 Floor Plate and Netrin-1 Are Involved in the Migration and Survival of Inferior Olivary Neurons Evelyne Bloch-Gallego,1 Fre´de´ ric Ezan,1 Marc Tessier-Lavigne,2 and Constantino Sotelo1 1Institut National de la Sante´ et de la Recherche Me´ dicale U106, Hoˆ pital de la Salpeˆ trie` re, 75013 Paris, France, and 2Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Department of Anatomy, University of California at San Francisco, San Francisco, California 94143 During their circumferential migration, the nuclei of inferior oli- However, axons of the remaining olivary cell bodies located in vary neurons translocate within their axons until they reach the the vicinity of the floor plate still succeed in entering their target, floor plate where they stop, although their axons have already the cerebellum, but they establish an ipsilateral projection in- crossed the midline to project to the contralateral cerebellum. stead of the normal contralateral projection. In vitro experi- Signals released by the floor plate, including netrin-1, have ments involving ablations of the midline show a fusion of the been implicated in promoting axonal growth and chemoattrac- two olivary masses normally located on either side of the tion during axonal pathfinding in different midline crossing sys- ventral midline, suggesting that the floor plate may function as tems. In the present study, we report experiments that strongly a specific stop signal for inferior olivary neurons. These results suggest that the floor plate could also be involved in the establish a requirement for netrin-1 in the migration of inferior migration of inferior olivary neurons. -

The Cerebellum in Sagittal Plane-Anatomic-MR Correlation: 2

667 The Cerebellum in Sagittal Plane-Anatomic-MR Correlation: 2. The Cerebellar Hemispheres Gary A. Press 1 Thin (5-mm) sagittal high-field (1 .5-T) MR images of the cerebellar hemispheres James Murakami2 display (1) the superior, middle, and inferior cerebellar peduncles; (2) the primary white Eric Courchesne2 matter branches to the hemispheric lobules including the central, anterior, and posterior Dean P. Berthoty1 quadrangular, superior and inferior semilunar, gracile, biventer, tonsil, and flocculus; Marjorie Grafe3 and (3) several finer secondary white-matter branches to individual folia within the lobules. Surface features of the hemispheres including the deeper fissures (e.g., hori Clayton A. Wiley3 1 zontal, posterolateral, inferior posterior, and inferior anterior) and shallower sulci are John R. Hesselink best delineated on T1-weighted (short TRfshort TE) and T2-weighted (long TR/Iong TE) sequences, which provide greatest contrast between CSF and parenchyma. Correlation of MR studies of three brain specimens and 11 normal volunteers with microtome sections of the anatomic specimens provides criteria for identifying confidently these structures on routine clinical MR. MR should be useful in identifying, localizing, and quantifying cerebellar disease in patients with clinical deficits. The major anatomic structures of the cerebellar vermis are described in a companion article [1). This communication discusses the topographic relationships of the cerebellar hemispheres as seen in the sagittal plane and correlates microtome sections with MR images. Materials, Subjects, and Methods The preparation of the anatomic specimens, MR equipment, specimen and normal volunteer scanning protocols, methods of identifying specific anatomic structures, and system of This article appears in the JulyI August 1989 issue of AJNR and the October 1989 issue of anatomic nomenclature are described in our companion article [1]. -

Basal Ganglia & Cerebellum

1/2/2019 This power point is made available as an educational resource or study aid for your use only. This presentation may not be duplicated for others and should not be redistributed or posted anywhere on the internet or on any personal websites. Your use of this resource is with the acknowledgment and acceptance of those restrictions. Basal Ganglia & Cerebellum – a quick overview MHD-Neuroanatomy – Neuroscience Block Gregory Gruener, MD, MBA, MHPE Vice Dean for Education, SSOM Professor, Department of Neurology LUHS a member of Trinity Health Outcomes you want to accomplish Basal ganglia review Define and identify the major divisions of the basal ganglia List the major basal ganglia functional loops and roles List the components of the basal ganglia functional “circuitry” and associated neurotransmitters Describe the direct and indirect motor pathways and relevance/role of the substantia nigra compacta 1 1/2/2019 Basal Ganglia Terminology Striatum Caudate nucleus Nucleus accumbens Putamen Globus pallidus (pallidum) internal segment (GPi) external segment (GPe) Subthalamic nucleus Substantia nigra compact part (SNc) reticular part (SNr) Basal ganglia “circuitry” • BG have no major outputs to LMNs – Influence LMNs via the cerebral cortex • Input to striatum from cortex is excitatory – Glutamate is the neurotransmitter • Principal output from BG is via GPi + SNr – Output to thalamus, GABA is the neurotransmitter • Thalamocortical projections are excitatory – Concerned with motor “intention” • Balance of excitatory & inhibitory inputs to striatum, determine whether thalamus is suppressed BG circuits are parallel loops • Motor loop – Concerned with learned movements • Cognitive loop – Concerned with motor “intention” • Limbic loop – Emotional aspects of movements • Oculomotor loop – Concerned with voluntary saccades (fast eye-movements) 2 1/2/2019 Basal ganglia “circuitry” Cortex Striatum Thalamus GPi + SNr Nolte. -

L4-Physiology of Motor Tracts.Pdf

: chapter 55 page 667 Objectives (1) Describe the upper and lower motor neurons. (2) Understand the pathway of Pyramidal tracts (Corticospinal & corticobulbar tracts). (3) Understand the lateral and ventral corticospinal tracts. (4) Explain functional role of corticospinal & corticobulbar tracts. (5) Describe the Extrapyramidal tracts as Rubrospinal, Vestibulospinal, Reticulospinal and Tectspinal Tracts. The name of the tract indicate its pathway, for example Corticobulbar : Terms: - cortico: cerebral cortex. Decustation: crossing. - Bulbar: brainstem. Ipsilateral : same side. *So it starts at cerebral cortex and Contralateral: opposite side. terminate at the brainstem. CNS influence the activity of skeletal muscle through two set of neurons : 1- Upper motor neurons (UMN) 2- lower motor neuron (LMN) They are neurons of motor cortex & their axons that pass to brain stem and They are Spinal motor neurons in the spinal spinal cord to activate: cord & cranial motor neurons in the brain • cranial motor neurons (in brainstem) stem which innervate muscles directly. • spinal motor neurons (in spinal cord) - These are the only neurons that innervate - Upper motor neurons (UMN) are the skeletal muscle fibers, they function as responsible for conveying impulses for the final common pathway, the final link voluntary motor activity through between the CNS and skeletal muscles. descending motor pathways that make up by the upper motor neurons. Lower motor neurons are classified based on the type of muscle fiber the innervate: There are two UMN Systems through which 1- alpha motor neurons (UMN) control (LMN): 2- gamma motor neurons 1- Pyramidal system (corticospinal tracts ). 2- Extrapyramidal system The activity of the lower motor neuron (LMN, spinal or cranial) is influenced by: 1. -

Neurochemical and Structural Organization of the Principal Nucleus of the Inferior Olive in the Human

THE ANATOMICAL RECORD 294:1198–1216 (2011) Neurochemical and Structural Organization of the Principal Nucleus of the Inferior Olive in the Human JOAN S. BAIZER,1* CHET C. SHERWOOD,2 PATRICK R. HOF,3 4 5 SANDRA F. WITELSON, AND FAHAD SULTAN 1Department of Physiology and Biophysics, University at Buffalo, Buffalo, New York 2Department of Anthropology, The George Washington University, Washington, District of Columbia 3Department of Neuroscience and Friedman Brain Institute, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York, New York 4Department of Psychiatry & Behavioural Neurosciences, Michael G. DeGroote School of Medicine, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada L8N 3Z5 5Department of Cognitive Neurology, University of Tu¨ bingen, Tu¨ bingen, Germany ABSTRACT The inferior olive (IO) is the sole source of the climbing fibers that innervate the Purkinje cells of the cerebellar cortex. The IO comprises several subdivisions, the dorsal accessory olive (DAO), medial accessory olive (MAO), and principal nuclei of the IO (IOpr); the relative sizes of these subnuclei vary among species. In human, there is an expansion of the cerebellar hemispheres and a corresponding expansion of the IOpr. We have examined the structural and neurochemical organization of the human IOpr, using sections stained with cresyl violet (CV) or immuno- stained for the calcium-binding proteins calbindin (CB), calretinin (CR), and parvalbumin (PV), the synthetic enzyme for nitric oxide (nNOS), and nonphosphorylated neurofilament protein (NPNFP). We found qualitative differences in the folding patterns of the IOpr among individuals and between the two sides of the brainstem. Quantification of IOpr volumes and indices of folding complexity, however, did not reveal consistent left–right differences in either parameter. -

Occurrence of Long-Term Depression in the Cerebellar Flocculus During Adaptation of Optokinetic Response Takuma Inoshita, Tomoo Hirano*

SHORT REPORT Occurrence of long-term depression in the cerebellar flocculus during adaptation of optokinetic response Takuma Inoshita, Tomoo Hirano* Department of Biophysics, Graduate School of Science, Kyoto University, Sakyo-ku, Japan Abstract Long-term depression (LTD) at parallel fiber (PF) to Purkinje cell (PC) synapses has been considered as a main cellular mechanism for motor learning. However, the necessity of LTD for motor learning was challenged by demonstration of normal motor learning in the LTD-defective animals. Here, we addressed possible involvement of LTD in motor learning by examining whether LTD occurs during motor learning in the wild-type mice. As a model of motor learning, adaptation of optokinetic response (OKR) was used. OKR is a type of reflex eye movement to suppress blur of visual image during animal motion. OKR shows adaptive change during continuous optokinetic stimulation, which is regulated by the cerebellar flocculus. After OKR adaptation, amplitudes of quantal excitatory postsynaptic currents at PF-PC synapses were decreased, and induction of LTD was suppressed in the flocculus. These results suggest that LTD occurs at PF-PC synapses during OKR adaptation. DOI: https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.36209.001 Introduction The cerebellum plays a critical role in motor learning, and a type of synaptic plasticity long-term *For correspondence: depression (LTD) at parallel fiber (PF) to Purkinje cell (PC) synapses has been considered as a primary [email protected]. cellular mechanism for motor learning (Ito, 1989; Hirano, 2013). However, the hypothesis that LTD ac.jp is indispensable for motor learning was challenged by demonstration of normal motor learning in Competing interests: The rats in which LTD was suppressed pharmacologically or in the LTD-deficient transgenic mice authors declare that no (Welsh et al., 2005; Schonewille et al., 2011). -

Cerebellum and Inferior Olive

Cerebellum and Inferior Olivary Nucleus Spinocerebellum • Somatotopically organised (vermis controls axial musculature; intermediate hemisphere controls limb musculature) • Control of body musculature • Inputs… Vermis receives somatosensory information (mainly from the trunk) via the spinocerebellar tracts and from the spinal nucleus of V. It receives a direct projection from the primary sensory neurons of the vestibular labyrinth, and also visual and auditory input from brain stem nuclei. • Intermediate hemisphere receives somatosensory information (mainly from the limbs) via the spinocerebellar tracts (the dorsal spinocerebellar tract, from Clarke’s nucleus of the lower limb, and the cuneocerebellar tract, from the accessory cu- neate nucleus of the upper limb, carry information from muscle spindle afferents; both enter via the ipsilateral inferior cerebellar peduncle). • An internal feedback signal arrives via the ventral spinocerebellar tract (lower limb) and rostral spinocerebellar tract (upper limb). (Ventral s.t. decussates in the spinal cord and enters via the superior cerebellar peduncle, but some fibres re-cross in the cerebellum; rostral s.t. is an ipsilateral pathway and enters via sup. & inf. cerebellar peduncles.) • Outputs to fastigial nucleus, which projects to the medial descending systems: (1) reticulospinal tract [? n. reticularis teg- menti pontis and prepositus hypoglossi?]; (2) vestibulospinal tract [lateral and descending vestibular nn.]; and (3) an as- cending projection to VL thalamus [Å cells of origin of the ventral corticospinal tract]; (4) reticular grey of the midbrain [=periaqueductal?]; (5) inferior olive [medial accessory, MAO]. • … and interposed nuclei, which project to the lateral descending systems: (1) magnocellular portion of red nucleus [Å ru- brospinal tract]; (2) VL thalamus [Å motor cx which gives rise to lateral corticospinal tract]; (3) reticular nucleus of the pontine tegmentum; (4) inferior olive [dorsal accessory, DAO]; (5) spinal cord intermediate grey. -

Hypertrophic Olivary Degeneration Secondary to Traumatic Brain Injury: a Unique Form of Trans-Synaptic Degeneration Raman Mehrzad,1 Michael G Ho2

… Images in BMJ Case Reports: first published as 10.1136/bcr-2015-210334 on 2 July 2015. Downloaded from Hypertrophic olivary degeneration secondary to traumatic brain injury: a unique form of trans-synaptic degeneration Raman Mehrzad,1 Michael G Ho2 1Department of Medicine, DESCRIPTION haemorrhagic left superior cerebellar peduncle, all Steward Carney Hospital, Tufts A 33-year-old man with a history of traumatic brain consistent with his prior TBI. Moreover, the right University School of Medicine, Boston, Massachusetts, USA injury (TBI) from a few years prior, secondary to a inferior olivary nucleus was enlarged, which is 2Department of Neurology, high-speed motor vehicle accident, presented with exemplified in unilateral right hypertrophic olivary Steward Carney Hospital, Tufts worsening right-sided motor function. Brain MRI degeneration (HOD), likely secondary to the haem- University School of Medicine, showed diffuse axonal injury, punctuate microbleed- orrhagic lesion within the left superior cerebellar Boston, Massachusetts, USA ings, asymmetric Wallerian degeneration along the peduncle, causing secondary degeneration of the fi – Correspondence to left corticospinal tract in the brainstem and contralateral corticospinal tracts ( gures 1 6). Dr Raman Mehrzad, [email protected] Accepted 11 June 2015 http://casereports.bmj.com/ fl Figure 3 Brain axial gradient echo MRI showing Figure 1 Brain axial uid-attenuated inversion recovery haemosiderin products in the left superior cerebellar MRI showing hypertrophy of the right inferior olivary peduncle. nucleus. on 25 September 2021 by guest. Protected copyright. To cite: Mehrzad R, Ho MG. BMJ Case Rep Published online: [please include Day Month Year] Figure 2 Brain axial T2 MRI showing increased T2 Figure 4 Brain axial gradient echo MRI showing doi:10.1136/bcr-2015- signal change and hypertrophy of the right inferior evidence of haemosiderin products in the left>right 210334 olivary nucleus. -

Holmes Tremor in Association with Bilateral Hypertrophic Olivary Degeneration and Palatal Tremor

Arq Neuropsiquiatr 2003;61(2-B):473-477 HOLMES TREMOR IN ASSOCIATION WITH BILATERAL HYPERTROPHIC OLIVARY DEGENERATION AND PALATAL TREMOR CHRONOLOGICAL CONSIDERATIONS Case report Carlos R.M. Rieder1, Ricardo Gurgel Rebouças2, Marcelo Paglioli Ferreira3 ABSTRACT - Hypertrophic olivary degeneration (HOD) is a rare type of neuronal degeneration involving the dento-rubro-olivary pathway and presents clinically as palatal tremor. We present a 48 year old male patient who developed Holmes’ tremor and bilateral HOD five months after brainstem hemorrhage. The severe rest tremor was refractory to pharmacotherapy and botulinum toxin injections, but was markedly reduced after thalamotomy. Magnetic resonance imaging permitted visualization of HOD, which appeared as a characteristic high signal intensity in the inferior olivary nuclei on T2- and proton-density-weighted images. Enlargement of the inferior olivary nuclei was also noted. Palatal tremor was absent in that moment and appears about two months later. The delayed-onset between insult and tremor following structural lesions of the brain suggest that compensatory or secondary changes in nervous system function must contribute to tremor genesis. The literature and imaging findings of this uncommon condition are reviewed. KEY WORDS: rubral tremor, midbrain tremor, Holmes’ tremor, myorhythmia, palatal myoclonus. Tremor de Holmes em associação com degeneração olivar hipertrófica bilateral e tremor palatal: considerações cronológicas. Relato de caso RESUMO - Degeneração olivar hipertrófica (DOH) é um tipo raro de degeneração neuronal envolvendo o trato dento-rubro-olivar e se apresenta clinicamente como tremor palatal. Relatamos o caso de um homem de 48 anos que desenvolveu tremor de Holmes e DOH bilateral cinco meses após hemorragia em tronco encefálico. -

External and Internal Modulation of the Olivo-Cerebellar Loop

REVIEW ARTICLE published: 19 April 2013 NEURAL CIRCUITS doi: 10.3389/fncir.2013.00073 In and out of the loop: external and internal modulation of the olivo-cerebellar loop Avraham M. Libster 1,2* and Yo s e f Ya ro m 1,2 1 Department of Neurobiology, Life Science Institute, Hebrew University, Jerusalem, Israel 2 Edmund and Lily Safra Center for Brain Sciences, Hebrew University, Jerusalem, Israel Edited by: Cerebellar anatomy is known for its crystal like structure, where neurons and connections Egidio D’Angelo, University of are precisely and repeatedly organized with minor variations across the Cerebellar Cortex. Pavia, Italy The olivo-cerebellar loop, denoting the connections between the Cerebellar cortex, Inferior Reviewed by: Olive and Cerebellar Nuclei (CN), is also modularly organized to form what is known as Gilad Silberberg, Karolinska Institute, Sweden the cerebellar module. In contrast to the relatively organized and static anatomy, the Deborah Baro, Georgia cerebellum is innervated by a wide variety of neuromodulator carrying axons that are State University, USA heterogeneously distributed along the olivo-cerebellar loop, providing heterogeneity to the *Correspondence: static structure. In this manuscript we review modulatory processes in the olivo-cerebellar Avraham M. Libster, Department loop. We start by discussing the relationship between neuromodulators and the animal of Neurobiology, Life Science Institute, Hebrew University, behavioral states. This is followed with an overview of the cerebellar neuromodulatory Silberman Building, Jerusalem signals and a short discussion of why and when the cerebellar activity should be 91904, Israel. modulated. We then devote a section for three types of neurons where we briefly review e-mail: [email protected] its properties and propose possible neuromodulation scenarios. -

…Going One Step Further

…going one step further C20 (1017868) 2 Latin A Encephalon Mesencephalon B Telencephalon 31 Lamina tecti B1 Lobus frontalis 32 Tegmentum mesencephali B2 Lobus temporalis 33 Crus cerebri C Diencephalon 34 Aqueductus mesencephali D Mesencephalon E Metencephalon Metencephalon E1 Cerebellum 35 Cerebellum F Myelencephalon a Vermis G Circulus arteriosus cerebri (Willisii) b Tonsilla c Flocculus Telencephalon d Arbor vitae 1 Lobus frontalis e Ventriculus quartus 2 Lobus parietalis 36 Pons 3 Lobus occipitalis f Pedunculus cerebellaris superior 4 Lobus temporalis g Pedunculus cerebellaris medius 5 Sulcus centralis h Pedunculus cerebellaris inferior 6 Gyrus precentralis 7 Gyrus postcentralis Myelencephalon 8 Bulbus olfactorius 37 Medulla oblongata 9 Commissura anterior 38 Oliva 10 Corpus callosum 39 Pyramis a Genu 40 N. cervicalis I. (C1) b Truncus ® c Splenium Nervi craniales d Rostrum I N. olfactorius 11 Septum pellucidum II N. opticus 12 Fornix III N. oculomotorius 13 Commissura posterior IV N. trochlearis 14 Insula V N. trigeminus 15 Capsula interna VI N. abducens 16 Ventriculus lateralis VII N. facialis e Cornu frontale VIII N. vestibulocochlearis f Pars centralis IX N. glossopharyngeus g Cornu occipitale X N. vagus h Cornu temporale XI N. accessorius 17 V. thalamostriata XII N. hypoglossus 18 Hippocampus Circulus arteriosus cerebri (Willisii) Diencephalon 1 A. cerebri anterior 19 Thalamus 2 A. communicans anterior 20 Sulcus hypothalamicus 3 A. carotis interna 21 Hypothalamus 4 A. cerebri media 22 Adhesio interthalamica 5 A. communicans posterior 23 Glandula pinealis 6 A. cerebri posterior 24 Corpus mammillare sinistrum 7 A. superior cerebelli 25 Hypophysis 8 A. basilaris 26 Ventriculus tertius 9 Aa. pontis 10 A. -

Cerebellum and Activation of the Cerebellum IO ST During Nonmotor Tasks

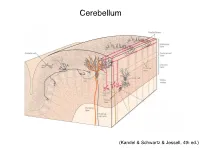

Cerebellum (Kandel & Schwartz & Jessell, 4th ed.) Granule186 cells are irreducibly smallChapter (6-8 7 μm) stellate cell basket cell outer synaptic layer PC rs cap PC layer grc Go inner 6 μm synaptic layer Figure 7.15 Largest cerebellar neuron occupies more than a 1,000-fold greater volume than smallest neuron. Thin section (~1 μ m) through monkey cerebellar cortex. Purkinje cell body (PC) and nucleus are far larger than those of granule cell (grc). The latter cluster to leave space for mossy fiber terminals to form glomeruli with grc dendritic claws and space for Golgi cells (Go). Note rich network of capillaries (cap). Fine, scat- tered dots are mitochondria. Courtesy of E. Mugnaini. brain ’ s most numerous neuron, this small cost grows large (see also chapter 13). Much of the inner synaptic layer is occupied by the large axon terminals of mossy fibers (figures 7.1 and 7.16). A terminal interlaces with multiple (~15) dendritic claws, each from a different but neighboring granule cell, and forms a complex knot (glomerulus ), nearly as large as a granule cell body (figures 7.1 and 7.16). The mossy fiber axon fires at an unusually high mean rate (up to 200 Hz) and is therefore among the brain’ s thickest (figure 4.6). To match the axon’ s high rate, a terminal expresses 150 active zones, 10 per postsynaptic granule cell (figure 7.16). These sites are capable of driving … and most expensive. 190 Chapter 7 10 4 8 3 9 19 10 10 × 6 × 2 2 4 ATP/s/cell ATP/s/cell ATP/s/m 1 2 0 0 astrocyte astrocyte Golgi cell Golgi cell basket cell basket cell stellate cell stellate cell granule cell granule cell mossy fiber mossy fiber Purkinje cell Purkinje Purkinje cell Purkinje Bergman glia Bergman glia climbing fiber climbing fiber Figure 7.18 Energy costs by cell type.