The Interface IBM and the Transformation of Corporate Design 1945 –1976

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bauhaus 1 Bauhaus

Bauhaus 1 Bauhaus Staatliches Bauhaus, commonly known simply as Bauhaus, was a school in Germany that combined crafts and the fine arts, and was famous for the approach to design that it publicized and taught. It operated from 1919 to 1933. At that time the German term Bauhaus, literally "house of construction" stood for "School of Building". The Bauhaus school was founded by Walter Gropius in Weimar. In spite of its name, and the fact that its founder was an architect, the Bauhaus did not have an architecture department during the first years of its existence. Nonetheless it was founded with the idea of creating a The Bauhaus Dessau 'total' work of art in which all arts, including architecture would eventually be brought together. The Bauhaus style became one of the most influential currents in Modernist architecture and modern design.[1] The Bauhaus had a profound influence upon subsequent developments in art, architecture, graphic design, interior design, industrial design, and typography. The school existed in three German cities (Weimar from 1919 to 1925, Dessau from 1925 to 1932 and Berlin from 1932 to 1933), under three different architect-directors: Walter Gropius from 1919 to 1928, 1921/2, Walter Gropius's Expressionist Hannes Meyer from 1928 to 1930 and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe Monument to the March Dead from 1930 until 1933, when the school was closed by its own leadership under pressure from the Nazi regime. The changes of venue and leadership resulted in a constant shifting of focus, technique, instructors, and politics. For instance: the pottery shop was discontinued when the school moved from Weimar to Dessau, even though it had been an important revenue source; when Mies van der Rohe took over the school in 1930, he transformed it into a private school, and would not allow any supporters of Hannes Meyer to attend it. -

Data Processing with Unit Record Equipment in Iceland

Data Processing with Unit Record Equipment in Iceland Óttar Kjartansson (Retired) Manager of Data Processing Department at Skýrr, Iceland [email protected] Abstract. This paper presents an overview of the usage of unit record equipment and punched cards in Iceland and introduces some of the pioneers. The usage of punched cards as a media in file processing started 1949 and became the dominant machine readable media in Iceland until 1968. After that punched cards were still used as data entry media for a while but went completely out of use in 1982. Keywords: Data processing, unit record, punched card, Iceland. 1 Hagstofa Íslands Hagstofa Íslands (Statistical Bureau of Iceland) initiated the use of 80 column punched cards and unit record equipment in Iceland in the year 1949. The first ma- chinery consisted of tabulating machine of the type IBM 285 (handled numbers only), the associated key punch machines, verifiers, and a card sorter. See Figures 1 and 2. This equipment was primarily used to account for the import and export for Iceland. Skýrr (Skýrsluvélar ríkisins og Reykjavíkurborgar - The Icelandic State and Munici- pal Data Center) was established three years later by an initiative from Hagstofa Íslands, Rafmagnsveita Reykjavíkur (Reykjavík Electric Power Utility), and the Medical Director of Health of Iceland as was described in an earlier article [3]. Fig. 1. IBM 285 Electric Accounting Machine at Hagstofa Íslands year 1949 J. Impagliazzo, T. Järvi, and P. Paju (Eds.): HiNC 2, IFIP AICT 303, pp. 225–229, 2009. © IFIP International Federation for Information Processing 2009 226 Ó. Kjartansson Fig. 2. Early form of the data registration using a punched card. -

Futurama 45 Minutes

<Segment Title> 3/19/03 11:35 PM study time Futurama 45 minutes - An essay by Roland Marchand, "The Designers go to the Fair, II: Norman Bel Geddes, The General Motors "Futurama", and the Visit to the Factory Transformed" from the book Design History: An Anthology. Dennis P. Doordan (1995). Cambridge: The MIT Press. During the 1930s, the early flowering of the industrial design profession in the United States coincided with an intense concern with public relations on the part of many depression-chastened corporations.(1) Given this conjunction, it is not surprising that an increasingly well-funded and sophisticated corporate presence was evident at the many national and regional fairs that characterized the decade. Beginning with the depression-defying 1933-34 Century of Progress Exposition in Chicago, major corporations invested unprecedented funds in the industrial exhibits that also marked expositions in San Diego in 1935, in Dallas and Cleveland in 1936, in Miami in 1937, and in San Francisco in 1939. The decade's pattern of increasing investments in promotional display reached a climax with the 1939-40 World's Fair in New York City. Leaders in the new field of industrial design took advantage of the escalating opportunities to devise corporate exhibits for these frequent expositions. Walter Dorwin Teague led the way with his designs for Bausch & Lomb, Eastman Kodak, and the Ford Motor Company for the 1933-34 exposition in Chicago. In 1936 he designed the Ford, Du Pont, and Texaco exhibits at Dallas and three years later claimed responsibility for seven major corporate exhibits at the New York World's Fair—those of Ford, Du Pont, United States Steel, National Cash Register, Kodak, Texaco, and Consolidated Edison. -

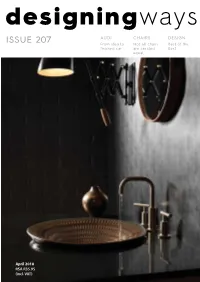

ISSUE 207 from Idea to Not All Chairs Best of the Finished Car Are Created Best Equal DESIGNING WAYS for People in the World of Design

THE GLOBAL FAVOURITE IN WINDOW DECORATION B-Range in Snow White April 2018 April designingways AUDI CHAIRS DESIGN ISSUE 207 From idea to Not all chairs Best of the finished car are created Best equal DESIGNING WAYS for people in the world of design TAYLOR ROLLER BLIND COLLECTION GOOD GLARE & EASY FLAME AUTOMATED SUITABLE FOR ANTIMICROBIAL UV CONTROL HEAT REDUCTION TO CLEAN RETARDANT OR MANUAL MOIST CONDITIONS Issue No. 207 Issue No. Contact us on 0861-1-TAYLOR (829567) www.taylorblinds.co.za April 2018 for an obligation-free quote and expert advice. @TaylorShutters RSA R35.95 BLINDS & SHUTTERS Est.1959 (incl. VAT) dw • April 2018 i A Stylish Addition enerations of experience and distinctive British design are the foundation of the Romo Gbrand. Renowned for its assorted library of classic and contemporary fabrics and wallcoverings, Romo offers a diverse style and timeless elegance enriched with a sophisticated colour palette. Through an exclusive collaboration with renowned rug manufacturer Louis de Poortere, Romo has designed a striking collection of textural flat weave and luxurious hand tufted rugs featuring timeless Romo designs. Using alluring soft chenilles and sumptuous wool yarns, Romo’s finest designs have been expertly reinterpreted as exquisite floorcoverings. FLAT WEAVE RUGS oven with soft chenille, Villa Nova’s range of flat weave rugs incorporate subtle variations of colour and interesting Wtextures. Using intricate woven details, these stunning rugs perfectly capture the essence of the original Villa Nova fabric. ii April 2018 • dw dw • April 2018 1 UPHOLSTERY LEATHER SYNTHETIC FABRICS CUSTOM FURNITURE Combining artistry and craftsmanship Kohler’s Artist Editions Taylor’s blind product range comprises systems, fabrics and basin collection adds personality to any bathroom. -

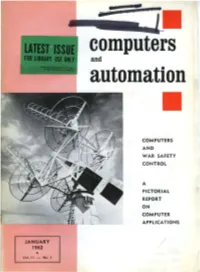

Computers and Automation

. 7 .7 BP S' J I i2z7itltJ2f computers and automation COMPUTERS AND WAR SAFETY CONTROL A PICTORIAL REPORT ON COMPUTER APPLICATIONS JANUARY 1962 / • Vol. 11 - No.1 GET RESULTS AND RELAXATION .. DIVIDENDS FROM STATISTICAL'S DATA-PROCESSING • oj ~/ si ---0--- rr e~ /~ When data-processing problems s( put the pressure on you, you'll find n the "safety valve" you need at q STATISTICAL. A wealth of experience is always ready to go to work for you "0: here. Behind every assignment is a searching understanding of management problems and solutions ... gained in serving America's top companies since 1933. From this experience comes the consistently-high quality service you would expect from America's oldest and largest independent data-processing and computer service. Sophisticated methods. Responsible personnel. The latest electronic equipment. Coast-to-coast facilities. Advantages like these add up to "know-how" and TABULATING CORPORATION C "show-how" that can not be acquired overnight. il NATIONAL HEADQUARTERS n This experience-in-depth service is available to 104 South Michigan Avenue-Chicago 3, Illinois a you day or night. A call to our m~arest OFFICES IN PRINCIPAL CITIES - COAST TO COAST data-processing and computer center will bring you the results you want ... and relaxation. ,,1/ -/p~ THE STATISTICAL MARK OF EXCELLENCE I 2 CO~IPUTERS and AUTOMATION for January, 1962 c ester, leI. / Park, ~. Y. Hyde U. S. 'J". Y. geles, City, ment. Lynn- Lab., :trical Alto, \rich. bury, Mass. '" Co., ~ssing Iberg, Ither, Icker- Ger- IS. Abbe 1 Mi- I des -- / "mus, Tele- data Alto, \Iich. -

Pan Am's Historic Contributions to Aircraft Cabin Design

German Aerospace Society, Hamburg Branch Hamburg Aerospace Lecture Series Dieter Scholz Pan Am's Historic Contributions to Aircraft Cabin Design Based on a Lecture Given by Matthias C. Hühne on 2017-05-18 at Hamburg University of Applied Sciences 2017-11-30 2 Abstract The report summarizes groundbreaking aircraft cabin developments at Pan American World Airways (Pan Am). The founder and chief executive Juan Terry Trippe (1899-1981) estab- lished Pan Am as the world's first truly global airline. With Trippe's determination, foresight, and strategic brilliance the company accomplished many pioneering firsts – many also in air- craft cabin design. In 1933 Pan Am approached the industrial designer Norman Bel Geddes (1893-1958). The idea was to create the interior design of the Martin M-130 flying boat by a specialized design firm. Noise absorption was optimized. Fresh air was brought to an agreea- ble temperature before it was pumped into the aircraft. Adjustable curtains at the windows made it possible to regulate the amount of light in the compartments. A compact galley was designed. The cabin layout optimized seating comfort and facilitated conversion to the night setting. The pre-war interior design of the Boeing 314 flying boat featured modern contours and colors. Meals were still prepared before flight and kept warm in the plane's galley. The innovative post-war land based Boeing 377 Stratocruiser had a pressurized cabin. The cabin was not divided anymore into compartments. Seats were reclining. The galley was well equipped. The jet age started at Pan Am with the DC-8 and the B707. -

Punched Card - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Page 1 of 11

.... _ ALL COMMUNICATIONS IN REFERENCE TO FORESTRY TO BE ADDRESSED TO THE CHIEF FORESTER VICTORIA. B.C. TIlE GO'IEIltDIEIIT Of THE P/IOVJII!;E DfBRItISH CIIJIIIIA DEPARTMENT OF LANDS FOREST BRANCH Yay 16th, 1928. H. J. Coles, Esq., Port Alberni, B.C. Please refer to File No. Management 081406 Dear Sirl- This is to advise that you passed the Licensed Scaler's Examina- tion held by Mr. A. L. Bryant a.t Vancouver, B.C., on May 2nd and 3rd, 1928. Your ~cence No. 811 is enclosed herewith. Xours truly, JM/pb • 1 Enc.l• N° 811 lHE 60VERNMIJIT OF '(f£ PROVINCe OF BRlnsH CIl.UIBIA FOREST ACT AND AMENDMENTS. ~raliug mirturt. FOREST BRANCH, LANDS DEPARTtvt~_NT. r)//) -4 ««e/<i;««<<<</tJ<<<<< < «««<<<<<<<<<<<<<<.<<. 192.K. .. W41n 1n tn (!1rrtify thatC~. /~~J.(~ff/~ -z::.~l::k~ -r1J->·r /7' £I P' . ;j residing at./!&~ L.1~~~-t.- Yi...-£" ~ ~ . ", in the Province of British Columbia, ;;.«~ ~ d-1~ ed ;22 2. / q "'r 8::. b has been examin /07 .••• =Zf'7;m .m.' mm.. .... ... m.................... /~ ..... .... ......... y •••• ««««<<<<<... - «««««< <(.,"F«<· < «. «<.««< of the Board of Examiners for Licensing alers, as provided in the "Forest Act" and amendments, and having creditably passed the said examination is hereby appointed a Licensed Scaler, and ·is duly authorized to perform the duties of a Licensed Scaler, as specified under Part VIII. of the "Forest <~:<~,.(_2.,_,;,::c,.(. «c.,"G~~< .. .. < ••• «« ••• «<•• CHAIRMAN OF BOARD OF EXAMINERS. Punched card - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Page 1 of 11 Punched card From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia A punched card (or punch card or Hollerith card or IBM card) is a piece of stiff paper that contains digital information represented by the presence or absence of holes in predefined positions. -

Confronting Privilege and Possibility at SANAA's Grace Farms

The Avery Review Sam holleran – Estate of Grace: Confronting Privilege and Possibility at SANAA’s Grace Farms New Canaan, Connecticut, has long been conflated with the WASPy ur-’burb Citation: Sam Holleran, “Estate of Grace: Confronting Privilege and Possibility at SANAA’s Grace Farms,” depicted in Rick Moody’s 1994 novel-turned-film The Ice Storm: popped in The Avery Review, no. 13 (February 2016), http:// collars, monogrammed bags, and picket fences. This image has been hard to averyreview.com/issues/13/estate-of-grace. shake for this high-income town at the end of a Metro-North rail spur, which is, to be sure, a comfortable place to live—far from the clamor of New York City but close to its jobs (and also reasonably buffered from the poorer, immi- grant-heavy pockets of Fairfield County that line Interstate 95). This community of 20,000 is blessed with rolling hills, charming historic architecture, and budgets big enough for graceful living. Its outskirts are latticed with old stone walls and peppered with luxe farmhouses and grazing deer. The town’s center, or “village district,” is a compact two-block elbow of shops that hinge from the rail depot (the arterial connection to New York City’s capital flows). Their exteriors are municipally regulated by Design Guidelines mandating Colonial building styles—red brick façades with white-framed windows, low-key signage, and other “charm-enhancing” elements. [1] The result is a New Urbanist core [1] The Town of New Canaan Village District Design Guidelines “Town of New Canaan Village District that is relatively pedestrian-friendly and pleasant, if a bit stuffy. -

5 Eliot Noyes and Associates. Westinghouse Tele-Computer

Eliot Noyes and Associates. Westinghouse Tele-Computer Center, near Pittsburgh, 1964. 5 Downloaded from http://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/pdf/10.1162/152638103322446451 by guest on 27 September 2021 Top: Eliot Noyes and Associates. Westinghouse Tele-Computer Center, near Pittsburgh, 1964. Plan. Bottom: Eliot Noyes and Associates. Tele-Computer Center, 1964. Interior. 6 Downloaded from http://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/pdf/10.1162/152638103322446451 by guest on 27 September 2021 The White Room: Eliot Noyes and the Logic of the Information Age Interior JOHN HARWOOD In a 1965 essay entitled “‘On Line’ in ‘Real Time,’” the editors of Fortune magazine described the advent of a new technological order that had already dramatically altered military planning and organization and would now impose itself upon business—the arrival of computer processing and management in “real time.” Members of Westinghouse Electric Corporation’s executive committee recently filed into a small room in the company’s new Tele-Computer Center near Pittsburgh and prepared to look at their business as no group of executives had ever looked at business before. In front of them was a large video screen, and to one side of the screen was a “remote inquiry” device that seemed a cross between a typewriter and a calculator. As the lights dimmed, the screen lit up with current reports from many of the company’s important divisions—news of gross sales, orders, profitability, inventory levels, manufacturing costs, and various measures of perfor- mance based on such data. When -

International Edition ACMRS PRESS 219

Spring 2021 CHICAGO International Edition ACMRS PRESS 219 ASSOCIATION OF UNIVERSITY PRESSES 283 AUTUMN HOUSE PRESS 194 BARD GRADUATE CENTER 165 BRANDEIS UNIVERSITY PRESS 168 CAMPUS VERLAG 256 CARNEGIE MELLON UNIVERSITY PRESS 185 CAVANKERRY PRESS 190 CSLI PUBLICATIONS 281 CONTENTS DIAPHANES 244 EPFL PRESS 275 General Interest 1 GALLAUDET UNIVERSITY PRESS 284 Academic Trade 19 GINGKO LIBRARY 202 Trade Paperbacks 29 HAU 237 Special Interest 39 ITER PRESS 263 Paperbacks 106 KAROLINUM PRESS, CHARLES UNIVERSITY PRAGUE 206 Distributed Books 118 KOÇ UNIVERSITY PRESS 240 Author Index 288 MUSEUM OF MODERN ART IN WARSAW 160 Title Index 290 NEW ISSUES POETRY AND PROSE 183 Guide to Subjects 292 OMNIDAWN PUBLISHING, INC. 177 Ordering Information Inside back cover PRICKLY PARADIGM PRESS 236 RENAISSANCE SOCIETY 163 SEAGULL BOOKS 118 SMART MUSEUM OF ART, UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO 161 TENOV BOOKS 164 UNIVERSITY OF ALASKA PRESS 213 UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS 1 UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI PRESS 199 THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS The Subversive Simone Weil A Life in Five Ideas Robert Zaretsky Distinguished literary biographer Robert Zaretsky upends our thinking on Simone Weil, bringing us a woman and a philosopher who is complicated and challenging, while remaining incredibly relevant. Known as the “patron saint of all outsiders,” Simone Weil (1909–43) was one of the twentieth century’s most remarkable thinkers, a philos- opher who truly lived by her political and ethical ideals. In a short life MARCH framed by the two world wars, Weil taught philosophy to lycée students 200 p. 5 1/2 x 8 1/2 and organized union workers, fought alongside anarchists during the ISBN-13: 978-0-226-54933-0 Spanish Civil War and labored alongside workers on assembly lines, Cloth $20.00/£16.00 joined the Free French movement in London and died in despair BIOGRAPHY PHILOSOPHY because she was not sent to France to help the Resistance. -

Organic Design, Moma 1940. the Breath of Modernity Arrives in Latin America

Organic Design, MoMA 1940. The Breath of Modernity Arrives in Latin America Oscar Salinas Flores Abstract Professor –specialized in design history– and researcher at the In 1940 MoMA New York Museum, called the cpuntry’s de- Industrial Design School and signers to present their best furniture designs inspired in the professor in Industrial Design new trend of organic design. Also, for the first time, designers Postgraduate Program, at the of another twenty Latin American countries were invited to National University of Mexico (UNAM). Permanent member participate in a contest with the hope they would reflect the of the International Conference identity of their region through forms and materials to express Board, of ICHDS, and mem- their progress in design and that could even be commercialized ber of the Board of Trustees of in the United States. Design History Foundation in Barcelona. Director of Editorial Designio, Mexico City. This text analyzes the group of participants, shows the progress [email protected] of design in each of their countries, the prize expectations, and the subsequent events which showed the reality and the pos- Received : November 2014 sibilities of USA and Latin America. Approved: August 2014 Key words: Hegemonic history, micro history, modernism, de- sign pioneers. Revista KEPES Año 11 No. 10 enero-diciembre 2014, págs. 195-208 ISSN 1794-7111 Revista KEPES, Año 11 No. 10, enero-diciembre de 2014, págs. 195-203 Organic Design, MoMA, 1940. El soplo de la modernidad llega a Latinoamérica Resumen En 1940, el Museo de Arte Moderno de Nueva York convocó a los diseñadores del país a presentar los mejores diseños de mobiliario inspirados en la nueva tendencia del diseño orgánico. -

Sistemi Economici E Il Ruolo Della Tecnologia: Un'esplorazione Teorica

SISTEMI ECONOMICI E IL RUOLO DELLA TECNOLOGIA: UN’ESPLORAZIONE TEORICA SULLA DINAMICA STRUTTURALE Autore: ANA DUEK DISSERTAZIONE PROPOSTA ALLA FACOLTÀ DI SCIENZE ECONOMICHE UNIVERSITÀ DELLA SVIZZERA ITALIANA LUGANO PER IL CONSEGUIMENTO DEL PH.D. IN SCIENZE ECONOMICHE Copyright © 2007 Giuria Direttore di tesi: Prof. Giorgio Tonella Revisore interno: Prof. Mauro Baranzini Revisore esterno: Prof. Heinrich Bortis Questa ricerca è stata svolta presso la Facoltà di Scienze Economiche dell’Università della Svizzera Italiana, Lugano. Versione finale: Ottobre 2007. ABSTRACT I ABSTRACT This research examines theoretically the problem of structural change. It is, in particular, an analysis of how economic systems and economic theory deal with structural change. The emphasis of the research is on three central topics: economic theory, systems theory and technological change. The particular focus of Part I is on features of economic structure definition, representation and methods. Part II deals with systems as abstract objects and system theory vis-à-vis with its structural endeavour, therefore concepts were presented to deal with changing systems. But this research also focuses its attention, in Part III, on the dynamic and evolutionary character of the particular technological changes and their interactions with economic systems. Two examples of technological innovation — Computer and the Internet — will be used to examine, in a historical framework, the core of the structural change. Based on economics and system theory, but with a multidisciplinary view, the present research combines the more traditional historic view with complexity science to achieve a more robust view of the economic system and its structural analysis. RINGRAZIAMENTI II RINGRAZIAMENTI Sono grata ai Professori Giorgio Tonella, Mauro Baranzini e Francisco Louçã per il loro brillante supporto accademico.