Challenging Tradition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The American Abstract Artists and Their Appropriation of Prehistoric Rock Pictures in 1937

“First Surrealists Were Cavemen”: The American Abstract Artists and Their Appropriation of Prehistoric Rock Pictures in 1937 Elke Seibert How electrifying it must be to discover a world of new, hitherto unseen pictures! Schol- ars and artists have described their awe at encountering the extraordinary paintings of Altamira and Lascaux in rich prose, instilling in us the desire to hunt for other such discoveries.1 But how does art affect art and how does one work of art influence another? In the following, I will argue for a causal relationship between the 1937 exhibition Prehis- toric Rock Pictures in Europe and Africa shown at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) and the new artistic directions evident in the work of certain New York artists immediately thereafter.2 The title for one review of this exhibition, “First Surrealists Were Cavemen,” expressed the unsettling, alien, mysterious, and provocative quality of these prehistoric paintings waiting to be discovered by American audiences (fig. ).1 3 The title moreover illustrates the extent to which American art criticism continued to misunderstand sur- realist artists and used the term surrealism in a pejorative manner. This essay traces how the group known as the American Abstract Artists (AAA) appropriated prehistoric paintings in the late 1930s. The term employed in the discourse on archaic artists and artistic concepts prior to 1937 was primitivism, a term due not least to John Graham’s System and Dialectics of Art as well as his influential essay “Primitive Art and Picasso,” both published in 1937.4 Within this discourse the art of the Ice Age was conspicuous not only on account of the previously unimagined timespan it traversed but also because of the magical discovery of incipient human creativity. -

The Origins and Meanings of Non-Objective Art by Adam Mccauley

The Origins and Meanings of Non-Objective Art The Origins and Meanings of Non-Objective Art Adam McCauley, Studio Art- Painting Pope Wright, MS, Department of Fine Arts ABSTRACT Through my research I wanted to find out the ideas and meanings that the originators of non- objective art had. In my research I also wanted to find out what were the artists’ meanings be it symbolic or geometric, ideas behind composition, and the reasons for such a dramatic break from the academic tradition in painting and the arts. Throughout the research I also looked into the resulting conflicts that this style of art had with critics, academia, and ultimately governments. Ultimately I wanted to understand if this style of art could be continued in the Post-Modern era and if it could continue its vitality in the arts today as it did in the past. Introduction Modern art has been characterized by upheavals, break-ups, rejection, acceptance, and innovations. During the 20th century the development and innovations of art could be compared to that of science. Science made huge leaps and bounds; so did art. The innovations in travel and flight, the finding of new cures for disease, and splitting the atom all affected the artists and their work. Innovative artists and their ideas spurred revolutionary art and followers. In Paris, Pablo Picasso had fragmented form with the Cubists. In Italy, there was Giacomo Balla and his Futurist movement. In Germany, Wassily Kandinsky was working with the group the Blue Rider (Der Blaue Reiter), and in Russia Kazimer Malevich was working in a style that he called Suprematism. -

Bauhaus 1 Bauhaus

Bauhaus 1 Bauhaus Staatliches Bauhaus, commonly known simply as Bauhaus, was a school in Germany that combined crafts and the fine arts, and was famous for the approach to design that it publicized and taught. It operated from 1919 to 1933. At that time the German term Bauhaus, literally "house of construction" stood for "School of Building". The Bauhaus school was founded by Walter Gropius in Weimar. In spite of its name, and the fact that its founder was an architect, the Bauhaus did not have an architecture department during the first years of its existence. Nonetheless it was founded with the idea of creating a The Bauhaus Dessau 'total' work of art in which all arts, including architecture would eventually be brought together. The Bauhaus style became one of the most influential currents in Modernist architecture and modern design.[1] The Bauhaus had a profound influence upon subsequent developments in art, architecture, graphic design, interior design, industrial design, and typography. The school existed in three German cities (Weimar from 1919 to 1925, Dessau from 1925 to 1932 and Berlin from 1932 to 1933), under three different architect-directors: Walter Gropius from 1919 to 1928, 1921/2, Walter Gropius's Expressionist Hannes Meyer from 1928 to 1930 and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe Monument to the March Dead from 1930 until 1933, when the school was closed by its own leadership under pressure from the Nazi regime. The changes of venue and leadership resulted in a constant shifting of focus, technique, instructors, and politics. For instance: the pottery shop was discontinued when the school moved from Weimar to Dessau, even though it had been an important revenue source; when Mies van der Rohe took over the school in 1930, he transformed it into a private school, and would not allow any supporters of Hannes Meyer to attend it. -

Sculptural Cubism in Product Design: Using Design History As a Creative Tool

INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON ENGINEERING AND PRODUCT DESIGN EDUCATION 3 & 4 SEPTEMBER 2015, LOUGHBOROUGH UNIVERSITY, DESIGN SCHOOL, LOUGHBOROUGH, UK SCULPTURAL CUBISM IN PRODUCT DESIGN: USING DESIGN HISTORY AS A CREATIVE TOOL Augustine FRIMPONG ACHEAMPONG and Arild BERG Oslo and Akershus University College of Applied Sciences ABSTRACT In Jan Michl's "Taking down the Bauhaus Wall: Towards living design history as a tool for better design", he explains how the history of design can become a tool for future design practices. He emphasizes how the aesthetics of the past still exist in the present. Although there have been a great deal of studies on the history of design, not much emphasis has been placed on Cubism, which is a very important part of design history. Many designs of the past, such as in the field of architecture and jewellery design, took their inspiration from sculptural cubism. The research question is therefore "How has sculptural Cubism influenced contemporary student product-design practices?" One research method used was the literature review, which was chosen to investigate what has been done in the past. Other methods used were interviews and focus groups, which were chosen to investigate what some contemporary design students knew about cubism. The researcher will also look to solicit knowledge from people outside the design community regarding designers and the work they do, as well as the general impression they have concerning design history and cubism. The concept of Cubism has been used in branding and as a marketing tool and in communication. Keywords: Design history, contemporary design practice, sculptural cubism, aesthetics. -

Expressionism with Kandinsky's Circles

Expressionism with Kandinsky’s Circles Grade: 1st Medium: Painting Learning Objective: Students will create concentric circles with contrasting colors. They will choose colors to express personal relationships between color and mood. Author: Heather McClure-Coleman Elements of Art / Principles of Design Complementary Colors: contrasting colors; colors that are opposite on the color wheel, such as yellow/violet, blue/orange, and red/green. Contrast: a principle of design; a technique that shows differences in the elements of visual arts in an artwork, such as smooth/rough textures, light/dark colors, or thick/thin lines. Pattern: a principle of design; the repetition of the elements of visual arts in an organized way; pattern and rhythm are both created through repetition; see rhythm for examples of regular, alternating, random, and progressive rhythmic patterns. Shape: an element of visual arts; a two-dimensional (flat) area enclosed by a line: Geometric: shapes and/or forms that are based on mathematical principles, such as a square/cube, circle/sphere, triangle/cone, or pyramid. Organic: shapes and/or forms that are irregular, often curving or rounded, and more informal than geometric shapes. Symmetry : symmetrical/formal balance. having balance; exact appearance on opposite sides of a dividing line or plane. Value: an element of visual arts; the lightness and darkness of a line, shape, or form; a measure of relative lightness and darkness. Vocabulary Abstract: 1. a style of art that includes various types of avant-garde art of the 20th century; 2. images that have been altered from their realistic/natural appearance; images that have been simplified to reveal only basic contours/forms; 3. -

ISSUE 207 from Idea to Not All Chairs Best of the Finished Car Are Created Best Equal DESIGNING WAYS for People in the World of Design

THE GLOBAL FAVOURITE IN WINDOW DECORATION B-Range in Snow White April 2018 April designingways AUDI CHAIRS DESIGN ISSUE 207 From idea to Not all chairs Best of the finished car are created Best equal DESIGNING WAYS for people in the world of design TAYLOR ROLLER BLIND COLLECTION GOOD GLARE & EASY FLAME AUTOMATED SUITABLE FOR ANTIMICROBIAL UV CONTROL HEAT REDUCTION TO CLEAN RETARDANT OR MANUAL MOIST CONDITIONS Issue No. 207 Issue No. Contact us on 0861-1-TAYLOR (829567) www.taylorblinds.co.za April 2018 for an obligation-free quote and expert advice. @TaylorShutters RSA R35.95 BLINDS & SHUTTERS Est.1959 (incl. VAT) dw • April 2018 i A Stylish Addition enerations of experience and distinctive British design are the foundation of the Romo Gbrand. Renowned for its assorted library of classic and contemporary fabrics and wallcoverings, Romo offers a diverse style and timeless elegance enriched with a sophisticated colour palette. Through an exclusive collaboration with renowned rug manufacturer Louis de Poortere, Romo has designed a striking collection of textural flat weave and luxurious hand tufted rugs featuring timeless Romo designs. Using alluring soft chenilles and sumptuous wool yarns, Romo’s finest designs have been expertly reinterpreted as exquisite floorcoverings. FLAT WEAVE RUGS oven with soft chenille, Villa Nova’s range of flat weave rugs incorporate subtle variations of colour and interesting Wtextures. Using intricate woven details, these stunning rugs perfectly capture the essence of the original Villa Nova fabric. ii April 2018 • dw dw • April 2018 1 UPHOLSTERY LEATHER SYNTHETIC FABRICS CUSTOM FURNITURE Combining artistry and craftsmanship Kohler’s Artist Editions Taylor’s blind product range comprises systems, fabrics and basin collection adds personality to any bathroom. -

Spring 2004 Professor Caroline A. Jones Lecture Notes History, Theory and Criticism Section, Department of Architecture Week 9, Lecture 2

MIT 4.602, Modern Art and Mass Culture (HASS-D) Spring 2004 Professor Caroline A. Jones Lecture Notes History, Theory and Criticism Section, Department of Architecture Week 9, Lecture 2 PHOTOGRAPHY, PROPAGANDA, MONTAGE: Soviet Avant-Garde “We are all primitives of the 20th century” – Ivan Kliun, 1916 UNOVIS members’ aims include the “study of the system of Suprematist projection and the designing of blueprints and plans in accordance with it; ruling off the earth’s expanse into squares, giving each energy cell its place in the overall scheme; organization and accommodation on the earth’s surface of all its intrinsic elements, charting those points and lines out of which the forms of Suprematism will ascend and slip into space.” — Ilya Chashnik , 1921 I. Making “Modern Man” A. Kasimir Malevich – Suprematism 1) Suprematism begins ca. 1913, influenced by Cubo-Futurism 2) Suprematism officially launched, 1915 – manifesto and exhibition titled “0.10 The Last Futurist Exhibition” in Petrograd. B. El (Elazar) Lissitzky 1) “Proun” as utopia 2) Types, and the new modern man C. Modern Woman? 1) Sonia Terk Delaunay in Paris a) “Orphism” or “organic Cubism” 1911 b) “Simultaneous” clothing, ceramics, textiles, cars 1913-20s 2) Natalia Goncharova, “Rayonism” 3) Lyubov Popova, Varvara Stepanova stage designs II. Monuments without Beards -- Vladimir Tatlin A. Constructivism (developed in parallel with Suprematism as sculptural variant) B. Productivism (the tweaking of “l’art pour l’art” to be more socialist) C. Monument to the Third International (Tatlin’s Tower), 1921 III. Collapse of the Avant-Garde? A. 1937 Paris Exposition, 1937 Entartete Kunst, 1939 Popular Front B. -

Berta Fischer, Björn Dahlem, Naum Gabo Into Space

PRESS RELEASE Exhibtion Berta Fischer, Björn Dahlem, Naum Gabo Into Space Haus am Waldsee International Art in Berlin 18 October 2020 to 10 January 2021 Press preview: Fri, 16 October 2020, 11 am. Berta Fischer and Björn Dahlem will be present. „Into Space“ deals with the human longing for space, weightlessness, distant galaxies and the belief in hitherto incomprehensible energies beyond our perception. Three sculp- tors reflect upon the interfaces between art and science over a century and from Berlin. Following the exhibition „Lynn Chadwick, Hans Uhlmann, Katja Strunz“, which explored the subject of „Fold“ at Haus am Waldsee in 2019, Björn Dahlem (*1974), Berta Fischer (*1973) and Naum Gabo (1890 - 1977) are now taking up an artistic conversation about space and time between 1920 and 2020 with installations and sculptures. For Naum Gabo, art in the 1920s was a means of gaining knowledge about the physics of our planet. The Jewish-Russian artist, who had emigrated to Berlin, had shortly before written the „Realistic Manifesto“ with his brother Antoine Pevsner, which was ground-breaking for sculpture. He was constantly searching for new materials and means of expression, „not for the sake of the new, but to find expression for the new view of the world around me and for new insights into the forces of life and nature within me”. Even before the First World War, the latest disco- veries in natural science, Albert Einstein‘s theory of relativity and the idea of the fourth dimen- sion as hyperspaces had already profoundly shaken the previous understanding of the laws of nature, which Gabo experienced directly during his studies of medicine and natural sciences in Munich from 1910 onwards. -

The De Stijl Movement in the Netherlands and Related Aspects of Dutch Architecture 1917-1930

25 March 2002 Art History W36456 The De Stijl Movement in the Netherlands and related aspects of Dutch architecture 1917-1930. Walter Gropius, Design for Director’s Office in Weimar Bauhaus, 1923 Walter Gropius, Bauhaus Building, Dessau 1925-26 [Cubism and Architecture: Raymond Duchamp-Villon, Maison Cubiste exhibited at the Salon d’Automne, Paris 1912 Czech Cubism centered around the work of Josef Gocar and Josef Chocol in Prague, notably Gocar’s House of the Black Virgin, Prague and Apt. Building at Prague both of 1913] H.P. (Hendrik Petrus) Berlage Beurs (Stock Exchange), Amsterdam 1897-1903 Diamond Workers Union Building, Amsterdam 1899-1900 J.M. van der Mey, Michel de Klerk and P.L. Kramer’s work on the Sheepvaarthuis, Amsterdam 1911-16. Amsterdam School and in particular the project of social housing at Amsterdam South as well as other isolated housing estates in the expansion of the city. Michel de Klerk (Eigenhaard Development 1914-18; and Piet Kramer (De Dageraad c. 1920) chief proponents of a brick architecture sometimes called Expressionist Robert van t’Hoff, Villa ‘Huis ten Bosch at Huis ter Heide, 1915-16 De Stijl group formed in 1917: Piet Mondrian, Theo van Doesburg, Gerritt Rietveld and others (Van der Leck, Huzar, Oud, Jan Wils, Van t’Hoff) De Stijl (magazine) published 1917-31 and edited by Theo van Doesburg Piet Mondrian’s development of “Neo-Plasticism” in Painting Van Doesburg’s Sixteen Points to a Plastic Architecture Projects for exhibition at the Léonce Rosenberg Gallery, Paris 1923 (Villa à Plan transformable in collaboration with Cor van Eestern Gerritt Rietveld Red/Blue Chair c. -

David Quigley Learning to Live: Preliminary Notes for a Program Of

David Quigley In an essay published in 2009, Boris could play in a broader social context influenced the founding director John Groys makes the claim that “today art beyond the narrow realm of the art Andrew Rice, as well as the professors Learning to Live: education has no definite goal, no world. Josef Albers, Merce Cunningham, Robert Preliminary Notes method, no particular content that can Motherwell, John Cage, and the poets be taught, no tradition that can be Performing Pragmatism: Robert Creeley and Charles Olson. for a Program of Art transmitted to a new generation—which Art as Experience Unlike other trajectories of the critique Education for the is to say, it has too many.”69 While one On the first pages of Dewey’s Art as of the art object, the Deweyian tradition might agree with this diagnosis, one Experience from 1934, we read: did not deny the special status of art in 21st Century. immediately wonders how we should itself but rather resituated it within a Après John Dewey assess it. Are we to merely tacitly “By one of the ironic perversities that continuum of human experience. Dewey, acknowledge this situation or does this often attend the course of affairs, the as a thinker of egalitarianism and critique imply a call for change? Is this existence of the works of art upon which democracy, created a theory of art lack (or paradoxical overabundance) of the formation of an aesthetic theory based on the fundamental continuity goals, methods or content inherent to depends has become an obstruction of experience and practice, making the very essence of art education, or is to theory about them. -

Extended Sensibilities Homosexual Presence in Contemporary Art

CHARLEY BROWN SCOTT BURTON CRAIG CARVER ARCH CONNELLY JANET COOLING BETSY DAMON NANCY FRIED EXTENDED SENSIBILITIES HOMOSEXUAL PRESENCE IN CONTEMPORARY ART JEDD GARET GILBERT & GEORGE LEE GORDON HARMONY HAMMOND JOHN HENNINGER JERRY JANOSCO LILI LAKICH LES PETITES BONBONS ROSS PAXTON JODY PINTO CARLA TARDI THE NEW MUSEUM FRAN WINANT EXTENDED SENSIBILITIES HOMOSEXUAL PRESENCE IN CONTEMPORARY ART CHARLEY BROWN HARMONY HAMMOND SCOTT BURTON JOHN HENNINGER CRAIG CARVER JERRY JANOSCO ARCH CONNELLY LILI LAKICH JANET COOLING LES PETITES BONBONS BETSY DAMON ROSS PAXTON NANCY FRIED JODY PINTO JEDD GARET CARLA TARDI GILBERT & GEORGE FRAN WINANT LE.E GORDON Daniel J. Cameron Guest Curator The New Museum EXTENDED SENSIBILITIES STAFF ACTIVITIES COUNCJT . Robin Dodds Isabel Berley HOMOSEXUAL PRESENCE IN CONTEMPORARY ART Nina Garfinkel Marilyn Butler N Lynn Gumpert Arlene Doft ::;·z17 John Jacobs Elliot Leonard October 16-December 30, 1982 Bonnie Johnson Lola Goldring .H6 Ed Jones Nanette Laitman C:35 Dieter Morris Kearse Dorothy Sahn Maria Reidelbach Laura Skoler Rosemary Ricchio Jock Truman Ned Rifkin Charles A. Schwefel INTERNS Maureen Stewart Konrad Kaletsch Marcia Thcker Thorn Middlebrook GALLERY ATTENDANTS VOLUNTEERS Joanne Brockley Connie Bangs Anne Glusker Bill Black Marcia Landsman Carl Blumberg Sam Robinson Jeanne Breitbart Jennifer Q. Smith Mary Campbell Melissa Wolf Marvin Coats Jody Cremin This exhibition is supported by a grant from the National Endowment for BOARD OF TRUSTEES Joanna Dawe the Arts in Washington, D.C., a Federal Agency, and is made possible in Jack Boulton Mensa Dente part by public funds from the New York State Council on the Arts. Elaine Dannheisser Gary Gale Library of Congress Catalog Number: 82-61279 John Fitting, Jr. -

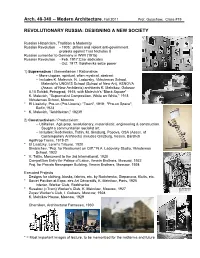

C:\Users\Kai\Documents\CMU Teaching\Modern\Handouts

Arch. 48-340 -- Modern Architecture, Fall 2011 Prof. Gutschow, Class #19 REVOLUTIONARY RUSSIA: DESIGNING A NEW SOCIETY Russian Historicism, Tradition & Modernity Russian Revolution - 1905: strikes and violent anti-government protests against Tsar Nicholas II Russian surrender to Germany in WWI (1915) Russian Revolution - Feb. 1917:Czar abdicates - Oct. 1917: Bolsheviks seize power 1) Suprematism / Elementarism / Rationalism -- More utopian, spiritual, often mystical, abstract -- Includes K. Malevich, N. Ladovsky, Vkhutemas School, Malevich's UNOVIS School (School of New Art), ASNOVA (Assoc. of New Architects) architects K. Melnikov, Golosov 0.10 Exhibit, Petrograd, 1915, with Malevich’s “Black Square” K. Malevich, "Suprematist Composition, White on White," 1918 Vkhutemas School, Moscow * El Lissitzky, Pro-un (Pro-Unovis): "Town", 1919; "Pro-un Space", Berlin,1923 * K. Malevich, "Arkhitekton," 1923ff 2) Constructivism / Productivism: -- Utilitarian, Agit-prop, revolutionary, materialistic, engineering & construction. Sought a communitarian socialist art. -- Includes: Rodchenko, Tatlin, M. Ginsburg, Popova, OSA (Assoc. of Contemporary Architects) includes Ginzburg, Vesnin, Barshch AgitProp Trains, 1919-21 * El Lissitzky, Lenin's Tribune, 1920 Simbirchev, “Proj. for Restaurant on Cliff," N.A. Ladovsky Studio, Vkhutemas School, 1922 * V. Tatlin, Monument to the 3rd International, 1920 Competition Entry for Palace of Labor, Vesnin Brothers, Moscow, 1922 Proj. for Pravda Newspaper Building, Vesnin Brothers, Moscow, 1924 Executed Projects Designs for clothing, kiosks, fabrics, etc. by Rodchenko, Stepanova, Klutis, etc. * Soviet Pavilion at Expo. des Art Décoratifs, K. Melnikov, Paris, 1925 Interior, Worker Club, Rodchenko * Rusakov (=Tram) Worker's Club, K. Melnikov, Moscow, 1927 Zuyev Worker's Club, I. Golosov, Moscow, 1928 K. Melnikov House, Moscow, 1929 Chernikov, Architectural Fantasies, 1930 * = Most important images of lecture, to be memorized for the midterms and future .