To Students in My Professional and Technical Writing Courses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marzo/March 2016 DOMUS 1000: UNA LETTURA DEL PASSATO, UNA FINESTRA SUL FUTURO, UN OMAGGIO ALLE ICONE DEL DESIGN ITALIANO. RACCOG

A € 25,00 / B € 21,00 / CH CHF 20,00 Poste Italiane S.p.A. marzo/march euro 10.00 CH Canton Ticino CHF 20,00 / D € 26,00 Spedizione in Abbonamento Postale D.L. 353/2003 Italy only E € 19,95 / F € 16,00 / I € 10,00 / J ¥ 3,100 (conv. in Legge 27/02/2004 n. 46), Articolo 1, 2016 periodico mensile NL € 16,50 / P € 19,00 / UK £ 16,50 / USA $ 33,95 Comma 1, DCB—Milano DOMUS 1000: UNA LETTURA DEL PASSATO, UNA FINESTRA SUL FUTURO, UN OMAGGIO ALLE ICONE DEL DESIGN ITALIANO. RACCOGLIENDO L’EREDITÀ DI PONTI, NOVE DIRETTORI RACCONTANO LA LORO DOMUS E LE SFIDE DEL NUOVO MILLENNIO DOMUS 1000: A READING OF THE PAST, A WINDOW ONTO THE FUTURE, AN HOMAGE TO THE ICONS OF ITALIAN DESIGN. IN THE WAKE OF GIO PONTI’S LEGACY, NINE EDITORS-IN-CHIEF SPEAK OF THEIR DOMUS STINT AND THE CHALLENGES OF THE NEW MILLENNIUM domus 1000 Marzo / March 2016 SOMMARIO/CONTENTS Autore / Author Titolo Title Fulvio Irace 1 Mille di queste Domus One thousand of these Domuses Giovanna Mazzocchi Bordone 2 Gianni e Giovanna Mazzocchi Gianni and Giovanna Mazzocchi Editori Publishers Fulvio Irace 4 I direttori e la storia The editors-in-chief and the history 6 Gio Ponti Gio Ponti 8 Lisa Lisa 10 Cara Domus... Dear Domus... 14 Architettura Architecture a cura di/guest editor 28 Exhibition Exhibitions Fulvio Irace 30 Domus Plus Domus Plus art direction 31 Extra Domus Extra Domus Italo Lupi Maria Grazia Mazzocchi 32 Pierre Restany Pierre Restany con la collaborazione grafica di/ with graphic assistance from Fulvio Irace 34 Arte Art Rosa Casamento (Studio Lupi) 38 Domus in numeri Domus in numbers Ivana Foti coordinamento / coordinator Donatella Bollani Miranda Giardino di Lollo Alessandro Mendini 41 1976-2016. -

From Architecture to Design and Back

Res Mobilis Revista internacional de investigación en mobiliario y objetos decorativos Vol. 9, nº. 10, 2020 FROM ARCHITECTURE TO DESIGN AND BACK: THE ARCHITECTURAL ROOTS OF THE ITALIAN DESIGN SYSTEM, 1920-1980 DE LA ARQUITECTURA AL DISEÑO IDA Y VUELTA: LAS RAÍCES ARQUITECTÓNICAS DEL SISTEMA DE DISEÑO ITALIANO, 1920-1980 Elena Dellapiana* Politecnico di Torino Fiorella Bulegato Università IUAV di Venezia Abstract The histories of Italian design and architecture may be more readily understood if one considers that many of the protagonists are architect-designers. Identifying the root of this convergence in an academic and professional educational system based on the idea of the "complete architect", trained to work at any scale of design, this paper frames the work of the architect-designers within the cultural, economic and manufacturing context of the period between the 1920s and 1980s, when for historical reasons their role became particularly significant. Furthermore, many design historians in Italy are the product of the same education as the architects, and having followed the same course of studies as the architectural historians, they acquired the same techniques of investigation and interpretation, which they later refined in their own fields. The theme is thus explored from the perspectives of the two authors, both architects but with specific training one as an architectural historian, and the other as a design historian. The relationship between the two research directions – the theoretical debate and its narrations, the relationship between designers and manufacturers – makes it possible to clarify some of the aspects that distinguish the history of Italian design culture compared to that of other Western nations. -

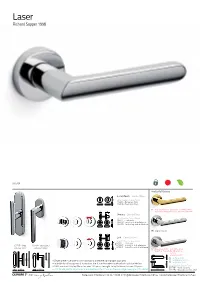

Richard Sapper 1998

Laser Richard Sapper 1998 M176R material/brass Escutcheon - Studio Olivari 51 Specification Code + Finish 1191E - European Style 1191O - Australian Style 10 60 IB superinox brass - guaranteed not to pitt or 13 34 tarnish for 30 years in sea air environments 60 Verona - Studio Olivari 30 Specification Code + Finish 51 H107S - snib only 47 H107V6 - privacy snib & eRelease H107F6 - indicating snib & eRelease 10 63 63 CR bright chrome 138 130 13 32 9 28 Link - Piero Lissoni Specification Code + Finish H200S - snib only 60 51 C176R - fixed K176R - operational 47 H200V6 - privacy snib & eRelease window slider window handle H200F6 - indicating snib & eRelease 5 10 IS superinox satin - guaranteed not to pitt or tarnish for 30 years in 60 sea air environments30 71 51 AS antique silver 126 166 PC powdercoat colours 150 • Single piece rose with torsion springs & a lifetime spring back warranty BZ antique bronze • Suitable for all European & Australian fire & non fire rated mortice locks & tube latches 63 63 • 100% made in Italy by Olivari for over 100 years, brought to by Bellevue for over 30 years Specification Code + Finish M176R1 - lever set only 37 62 32 66 • This handle and its accessories are available on the “L” low profile rose range. See page 19 for details 138 M176R2 - passage130 set incl. latch Bellevue Architectural | 03 9571 5666 | [email protected] | www.bellevuearchitectural.com.au 100 Years of Excellence pantone 5483 62 9 20 27 71 126 166 150 37 62 32 66 Bellevue Architectural | 03 9571 5666 | [email protected] | www.bellevuearchitectural.com.au 100 Years of Excellence pantone 5483 62 9 20 27 Richard Sapper Munich, 1932 Born in Munich, Sapper studied economy and engineering. -

Ts522d+S Radio.Cubo an Object That Goes Beyond Function

ts522D+S radio.cubo An object that goes beyond function. Designers M. Zanuso & R. Sapper Designers Marco Zanuso Designer, urban planner and architect, Marco Zanuso has stood since the Second World War as a leading protagonist in the Modern Movement cultural debate. Numerous collaborations illustrious during his career: the most significant ones stand out with brothers Livio, Pier Giacomo and Achille Castiglioni and Richard Sapper. Along with this has created – in 1962 – Doney, the TV for Brionvega. A successful challenge for the Italian brand, repeated – in the following years with the design of televisions Sirius (1964) and Black (1969) and the radio.cubo. Designers 720 Lady Designed in 1951 by Marco Zanuso for Arflex, the Lady armchair won the gold medal at the IX Milan Triennale in the same year. The armchair stands as a modern icon, the fruit of innovation that turned the traditional manufacturing technique for making armchairs and sofas on its head, with each part manufactured separately and then assembled. Today, the look of the Lady armchair has been made even more contemporary by a new selection of fabrics designed by Raf Simons and introduced to Cassina’s Everest collection. Year of design Year of production 1951 2015 Designers Richard Sapper Creator of true modern design masterpieces, has designed objects which have become cult icons over time, such as the Alessi Kettle 9091 (1982), the Tizio lamp (1972) for Artemide and the Grillo telephone (1965) for Siemens. As well as, of course, Brionvega radios and televisions. Eleven times Golden Compass, worked throughout his career with Fiat, Pirelli, IBM and Mercedes Benz. -

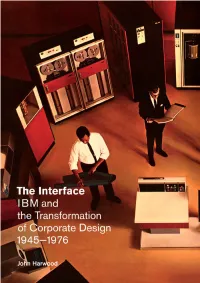

The Interface IBM and the Transformation of Corporate Design 1945 –1976

The Interface i This page intentionally left blank The Interface IBM and the Transformation of Corporate Design 1945 –1976 John Harwood A Quadrant Book University of Minnesota Press Minneapolis London Quadrant, a joint initiative of the University of Published by the Minnesota Press and the Institute for Advanced University of Minnesota Press Study at the University of Minnesota, provides 111 Third Avenue South, Suite 290 support for interdisciplinary scholarship within Minneapolis, MN 55401-2520 a new collaborative model of research and http://www.upress.umn.edu publication. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Sponsored by the Quadrant Design, Architecture, Harwood, John and Culture group (advisory board: John Archer, The interface : IBM and the transformation of Ritu Bhatt, Marilyn DeLong, Kate Solomonson) and corporate design, 1945–1976 / John Harwood. the University of Minnesota’s College of Design. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. Quadrant is generously funded by the Andrew W. ISBN 978-0-8166-7039-0 (hc : alk. paper) Mellon Foundation. ISBN 978-0-8166-7452-7 (pb : alk. paper) http://quadrant.umn.edu 1. International Business Machines Corporation— History. 2. Corporations—United States—History. This book is supported by a grant from the 3. Industrial design. 4. Modern movement Graham Foundation for Advanced Studies in the (Architecture)—United States. 5. Noyes, Eliot. Fine Arts. 6. Rand, Paul, 1914–1996. I. Title. HD9696.2.U64I2547 2011 Every effort was made to obtain permission to 338.7’6004097309045—dc23 reproduce material in this book. If any proper 2011031742 acknowledgment has not been included here, Printed in the United States of America on we encourage copyright holders to notify the acid-free paper publisher. -

Olivari Mini Catalog 113450.Pdf

Dal 1911 Olivari realizza maniglie in Italia, all’interno dei propri stabilimenti, dove si svolge l’intero ciclo produttivo. Partendo da barre in ottone, le maniglie vengono stampate, lavorate, smerigliate, lucidate, cromate e marchiate al laser. Olivari ha ottenuto le certificazioni ISO 9001 e ISO 14001 e si avvale delle tecnologie più evolute, ma ha mantenuto tutta la sapienza artigianale accumulata in cento anni di storia. Since 1911 Olivari has been manufacturing door handles at its own factories in Italy where the entire production process takes place. Starting with brass billets, the handles are forged, milled, polished, buffed, chrome-plated and hallmarked with a laser. Olivari has attained ISO 9001 and ISO 14001 certifications. Though it uses the most advanced technology, Olivari preserves all the artisanal wisdom it has accumulated in 100 years of history. pantone 5483 62 9 20 27 Fare bene, fare insieme Things well-done are done together In Olivari il lavoro è un patrimonio aziendale, che richiede il rispetto di standard elevati ma garantisce il riconoscimento dei meriti e delle capacità di ciascuno. In Olivari, il venerdì pomeriggio, l’ultima ora nuovo prodotto nel suo imballaggio finale, da cui dell’ultimo turno è sempre dedicata alla pulizia uscirà fresco, pulito, fragrante. Oggetti che spesso e al riordino della postazione di ciascuno. Non portano la firma di un nome importante, un c’è stata una disposizione dall’alto, un ordine di architetto famoso, un designer di successo, ma servizio che abbia imposto una corvée di pulizie oggetti che nascono dalle attenzioni quotidiane straordinaria; è una consuetudine che si è andata di tanti. -

Download File

The Responsibilities of the Architect: Mass Production and Modernism in the Work of Marco Zanuso 1936-1972 Shantel Blakely Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy under the Executive Committee of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2011 © 2011 Shantel Blakely All rights reserved ABSTRACT The Responsibilities of the Architect: Mass Production and Modernism in the Work of Marco Zanuso 1936-1972 Shantel Blakely The topic of this dissertation is the significance of industrial design in the work of architect Marco Zanuso (1916-2001), who lived and practiced in Milan, Italy. As a leading architect, as well as a pioneer in industrial design in the early postwar period, Zanuso was a key protagonist in the relationship of postwar Italian architecture culture to industrialization and capitalism. He is therefore an indicative figure with respect to the broader shift from Modernism to Postmodernism in architecture. Whereas previous studies of Zanuso have addressed either his architecture or his industrial design, this study traces the mutual influence of these practices in Zanuso's early work. The four chapters examine a selection of his projects to reconstruct their relationships to concurrent discourses in Italian art, architecture, and industry. In addition, the chapters show how these projects can be understood as conceptual and practical benchmarks along the way to the eventual realization of a continuum of design from small to large scale, and especially an architecture in which the serial nature of mass production would be explicit. The first chapter, whose topic is Zanuso's relationship to Italian modern architecture between the two World Wars, relates his embrace of mass-production around 1946, in essays on prefabricated architecture, to his student work in the 1930s and to his first projects during Reconstruction, emphasizing the influence of the Gruppo 7, Giuseppe Pagano, and Ernesto Nathan Rogers. -

Design Since 1945 This Book Has Received Significant Support from The

Design Since1945 PHILADELPHIA MUSEUM ART i Design Since 1945 This book has received significant support from the Graham Foundation for Advanced Studies in the Fine Arts. Major funding has also been provided by COLLAB: The Contemporary Design Group for the Philadelphia Museum of Art; The Pew Memorial Trust; and the Design Arts Program of the National Endowment for the Arts, a Federal agency. Design Since 1945 Organized by Jack Lenor Larsen Kathryn B. Hiesinger Olivier Mourgue George Nelson Editors Carl Pott Kathryn B. Hiesinger Jens Quistgaard George H. Marcus Dieter Rams Paul Reilly Contributing Authors Philip Rosenthal Max Bill Timo Sarpaneva Achille Castiglioni Ettore Sottsass, Jr. Bruno Danese Hans J. Wegner Niels Diffrient Marco Zanuso Herbert J. Gans Philadelphia Museum of Art 1983 This book accompanies the exhibition "Design Since 1945" at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, October 16, 1983, through January 8, 1984. The exhibition has been supported by generous grants from Best Products Company, Inc., The Pew Memorial Trust, and the National Endowment for the Humanities, a Federal agency. ERRATA 10: p 228 Dieter Rams biography, line delete "(1-37)." second sentence p. 235 Remhold Weiss biography, should read mixer Mi40 (1-37) are His award-winning table fan (1-50) and hand advo- considered models of the austere design and scientific method themselves to cated by both Ulm and Braun, products that lent of interre- systematic mathematical analysis, ordered assemblages lated component parts, p 246 Index, should read. Rams, Dieter 1-34-36, 111-72 Weiss, Remhold 1-37, 50 c Copyright 1983 by the Composition by Folio Typographers, Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Philadelphia Museum of Art All Pennsauken, N.J.