The Entire Modern Movement – Looked At

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Architectural Photography, the Farnsworth House, and the Opaque Discourse of Transparency SARAH M

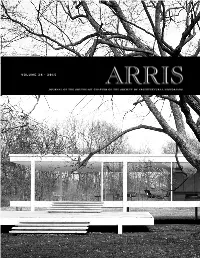

VOLUME 26 · 2015 JOURNAL OF THE SOUTHEAST CHAPTER OF THE SOCIETY OF ARCHITECTURAL HISTORIANS Volume 26 · 2015 1 Editors’ Note Articles 6 Madness and Method in the Junkerhaus: The Creation and Reception of a Singular Residence in Modern Germany MIKESCH MUECKE AND NATHANIEL ROBERT WALKER 22 Curtained Walls: Architectural Photography, the Farnsworth House, and the Opaque Discourse of Transparency SARAH M. DRELLER 40 The “Monster Problem”: Texas Architects Try to Keep it Cool Before Air Conditioning BETSY FREDERICK-ROTHWELL 54 Electrifying Entertainment: Social and Urban Modernization through Electricity in Savannah, Georgia JESSICA ARCHER Book Reviews 66 Cathleen Cummings, Decoding a Hindu Temple: Royalty and Religion in the Iconographic Program of the Virupaksha Temple, Pattadakal REVIEWED BY DAVID EFURD 68 Reiko Hillyer, Designing Dixie: Tourism, Memory, and Urban Space in the New South REVIEWED BY BARRY L. STIEFEL 70 Luis E, Carranza and Fernando L. Lara, Modern Architecture in Latin America: Art, Technology, and Utopia REVIEWED BY RAFAEL LONGORIA Field Notes 72 Preserving and Researching Modern Architecture Outside of the Canon: A View from the Field LYDIA MATTICE BRANDT 76 About SESAH ABSTRACTS Sarah M. Dreller Curtained Walls: Architectural Photography, the Farnsworth House, and the Opaque Discourse of Transparency Abstract This paper studies the creation, circulation, and reception of two groups of photographs of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s iconic Farnsworth House, both taken by Hedrich Blessing. The first set, produced for a 1951 Architectural Forum magazine cover story, features curtains carefully arranged according to the architect’s preferences; the Museum of Modern Art commis- sioned the second set in 1985 for a major Mies retrospective exhibition specifically because the show’s influential curator, Arthur Drexler, believed the curtains obscured Mies’ so-called “glass box” design. -

Street & Number 192 Cross Ridge Road___City Or Town New

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 10024-0018 (Oct. 1990) RECEIVED 2280 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service FR 2002 National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete me '" '"'' National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item be marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable". For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer to complete all items. 1. Name of Property_________________________________________________ historic name LANDIS GORES HOUSE other names/site number N/A 2. Location street & number 192 Cross Ridge Road_________ D not for publication city or town New Canaan________________ _______ D vicinity state Connecticut code CT county Fairfield code 001 zip code .06840. 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this Kl nomination D request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property H meets D does not meet the National Register criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant DnationaJly-C§ statewide D locally.^£]J5ee continuation sheet for additional comments.) February 4, 2002 Decertifying offfoffirritle ' Date Fohn W. -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. 1. Name of Property Historic name: __Norwich Mid-Century Modern Historic District_______ Other names/site number: ______________________________________ Name of related multiple property listing: _N/A__________________________________________________________ (Enter "N/A" if property is not part of a multiple property listing ____________________________________________________________________________ 2. Location Street & number: Parts of Hopson Road, Pine Tree Road, & Spring Pond Road___________ City or town: __Norwich__ State: _Vermont__ County: __Windsor__ Not For Publication: Vicinity: _____________________________________________________________________ _______ 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this nomination ___ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties -

Confronting Privilege and Possibility at SANAA's Grace Farms

The Avery Review Sam holleran – Estate of Grace: Confronting Privilege and Possibility at SANAA’s Grace Farms New Canaan, Connecticut, has long been conflated with the WASPy ur-’burb Citation: Sam Holleran, “Estate of Grace: Confronting Privilege and Possibility at SANAA’s Grace Farms,” depicted in Rick Moody’s 1994 novel-turned-film The Ice Storm: popped in The Avery Review, no. 13 (February 2016), http:// collars, monogrammed bags, and picket fences. This image has been hard to averyreview.com/issues/13/estate-of-grace. shake for this high-income town at the end of a Metro-North rail spur, which is, to be sure, a comfortable place to live—far from the clamor of New York City but close to its jobs (and also reasonably buffered from the poorer, immi- grant-heavy pockets of Fairfield County that line Interstate 95). This community of 20,000 is blessed with rolling hills, charming historic architecture, and budgets big enough for graceful living. Its outskirts are latticed with old stone walls and peppered with luxe farmhouses and grazing deer. The town’s center, or “village district,” is a compact two-block elbow of shops that hinge from the rail depot (the arterial connection to New York City’s capital flows). Their exteriors are municipally regulated by Design Guidelines mandating Colonial building styles—red brick façades with white-framed windows, low-key signage, and other “charm-enhancing” elements. [1] The result is a New Urbanist core [1] The Town of New Canaan Village District Design Guidelines “Town of New Canaan Village District that is relatively pedestrian-friendly and pleasant, if a bit stuffy. -

5 Eliot Noyes and Associates. Westinghouse Tele-Computer

Eliot Noyes and Associates. Westinghouse Tele-Computer Center, near Pittsburgh, 1964. 5 Downloaded from http://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/pdf/10.1162/152638103322446451 by guest on 27 September 2021 Top: Eliot Noyes and Associates. Westinghouse Tele-Computer Center, near Pittsburgh, 1964. Plan. Bottom: Eliot Noyes and Associates. Tele-Computer Center, 1964. Interior. 6 Downloaded from http://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/pdf/10.1162/152638103322446451 by guest on 27 September 2021 The White Room: Eliot Noyes and the Logic of the Information Age Interior JOHN HARWOOD In a 1965 essay entitled “‘On Line’ in ‘Real Time,’” the editors of Fortune magazine described the advent of a new technological order that had already dramatically altered military planning and organization and would now impose itself upon business—the arrival of computer processing and management in “real time.” Members of Westinghouse Electric Corporation’s executive committee recently filed into a small room in the company’s new Tele-Computer Center near Pittsburgh and prepared to look at their business as no group of executives had ever looked at business before. In front of them was a large video screen, and to one side of the screen was a “remote inquiry” device that seemed a cross between a typewriter and a calculator. As the lights dimmed, the screen lit up with current reports from many of the company’s important divisions—news of gross sales, orders, profitability, inventory levels, manufacturing costs, and various measures of perfor- mance based on such data. When -

Organic Design, Moma 1940. the Breath of Modernity Arrives in Latin America

Organic Design, MoMA 1940. The Breath of Modernity Arrives in Latin America Oscar Salinas Flores Abstract Professor –specialized in design history– and researcher at the In 1940 MoMA New York Museum, called the cpuntry’s de- Industrial Design School and signers to present their best furniture designs inspired in the professor in Industrial Design new trend of organic design. Also, for the first time, designers Postgraduate Program, at the of another twenty Latin American countries were invited to National University of Mexico (UNAM). Permanent member participate in a contest with the hope they would reflect the of the International Conference identity of their region through forms and materials to express Board, of ICHDS, and mem- their progress in design and that could even be commercialized ber of the Board of Trustees of in the United States. Design History Foundation in Barcelona. Director of Editorial Designio, Mexico City. This text analyzes the group of participants, shows the progress [email protected] of design in each of their countries, the prize expectations, and the subsequent events which showed the reality and the pos- Received : November 2014 sibilities of USA and Latin America. Approved: August 2014 Key words: Hegemonic history, micro history, modernism, de- sign pioneers. Revista KEPES Año 11 No. 10 enero-diciembre 2014, págs. 195-208 ISSN 1794-7111 Revista KEPES, Año 11 No. 10, enero-diciembre de 2014, págs. 195-203 Organic Design, MoMA, 1940. El soplo de la modernidad llega a Latinoamérica Resumen En 1940, el Museo de Arte Moderno de Nueva York convocó a los diseñadores del país a presentar los mejores diseños de mobiliario inspirados en la nueva tendencia del diseño orgánico. -

CT Fairfieldco Stmarksepiscop

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. 1. Name of Property Historic name: __St. Mark’s Episcopal Church________________________ Other names/site number: ______________________________________ Name of related multiple property listing: ___N/A________________________________________________________ (Enter "N/A" if property is not part of a multiple property listing ____________________________________________________________________________ 2. Location Street & number: _111 Oenoke Ridge___________________________________ City or town: _New Canaan_____ State: _Connecticut______ County: _Fairfield______ Not For Publication: Vicinity: __________________________________________________________________ __________ 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this nomination ___ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties -

Gerard & Kelly

Online Circulation: 9,900 FRIEZE / GERARD & KELLY / JULY 16, 2016 Gerard & Kelly By Evan Moffitt | July 16, 2016 The Glass House, New Canaan, Connecticut, USA The modernist philosophy of Le Corbusier, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and their contemporaries was demo- cratic and utopian – at least until it was realized in concrete, glass and steel. Despite its intention to pro- duce affordable designs for better living, modernism became the principle style for major corporations and government offices, for the architecture of capital and war. Are its original ideals still a worthy goal? I found myself asking that question at the Philip Johnson Glass House in New Canaan, Connecticut, while watch- ing Modern Living (2016), the latest work by performance artist duo Brennan Gerard and Ryan Kelly. As I followed the sloping path to Johnson’s jewel box, pairs of dancers dressed in colourful, loose-fitting garments, mimicking each other’s balletic movements, appeared in emerald folds of lawn. With no accompaniment but the chirping of birds and the crunch of gravel underfoot, I could’ve been watching tai chi at a West Coast meditation re- treat. The influence of postmodern California choreographers, such as the artists’ mentor Simone Forti, was clear. Gerard & Kelly, Modern Living, 2016, documentation of performance, The Glass House, New Canaan; pictured: Nathan Makolandra and Stephanie Amurao. Cour- tesy: Max Lakner/BFA.com When the Glass House was first completed in 1949, Johnson was criticised for producing a voyeuristic do- mestic space in an intensely private era governed by strict sexual mores. Like a fishbowl, the house gave its in- habitants nowhere to hide. -

EAMES HOUSE Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NFS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 EAMES HOUSE Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: Eames House Other Name/Site Number: Case Study House #8 2. LOCATION Street & Number: 203 N Chautauqua Boulevard Not for publication: N/A City/Town: Pacific Palisades Vicinity: N/A State: California County: Los Angeles Code: 037 Zip Code: 90272 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: x Building(s): x Public-Local: _ District: Public-State: _ Site: Public-Federal: Structure: Object: Number of Resources within Property Contributing: Noncontributing: 2 buildings sites structures objects Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: None Name of Related Multiple Property Listing: N/A NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NFS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 EAMES HOUSE Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this __ nomination __ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property __ meets __ does not meet the National Register Criteria. Signature of Certifying Official Date State or Federal Agency and Bureau In my opinion, the property __ meets __ does not meet the National Register criteria. -

National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form

NPS Form 10-900-b OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form This form is used for documenting property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin How to Complete the Multiple Property Documentation Form (formerly 16B). Complete each item by entering the requested information. X New Submission ________ Amended Submission A. Name of Multiple Property Listing Mid-Century Modern Residential Architecture in Norwich, Vermont B. Associated Historic Contexts (Name each associated historic context, identifying theme, geographical area, and chronological period for each.) I. Residential Architecture in Norwich, Vermont, 1945-1975 II. Architects Working in Norwich, Vermont, 1945-1975 C. Form Prepared by: name/title Lyssa Papazian & Brian Knight, Historic Preservation Consultants organization Lyssa Papazian Historic Preservation Consultant street & number 13 Dusty Ridge Road city or town Putney state Vermont zip code 05346 e-mail [email protected] telephone (802) 579-3698 date 6/20/19 D. Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this documentation form meets the National Register documentation standards and sets forth requirements for the listing of related properties consistent with the National Register criteria. This submission meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR 60 and the Secretary of the Interior’s Standards and Guidelines for Archeology and Historic Preservation. _______________________________ ______________________ _________________________ Signature of certifying official Title Date _____________________________________ State or Federal Agency or Tribal government I hereby certify that this multiple property documentation form has been approved by the National Register as a basis for evaluating related properties for listing in the National Register. -

Disgrace and Disavowal at the Philip Johnson Glass House

Adele Tutter 449 ADELE TUTTER, M.D., PH.D. The Path of Phocion: Disgrace and Disavowal at the Philip Johnson Glass House Philip Johnson graced his iconic Glass House with a single seicento painting, Landscape with the Burial of Phocion by Nicolas Pous- sin, an intrinsic signifier of the building that frames it. Analyzed within its physical, cultural, and political context, Burial of Phocion condenses displaced, interlacing representations of disavowed aspects of Johnson’s identity, including forbidden strivings for greatness and power, the haunting legacy of the lesser artist, and the humiliation of exile. It is argued that Phocion’s path from disgrace to posthumous dignity is a narrative lens through which Johnson attempted to reframe and disavow his political past. Every time I come away from Poussin I know better who I am. —attributed to PAUL CÉZANNE Is all that we see or seem But a dream within a dream? —EDGAR ALLAN POE, A DREAM WITHIN A DREAM, 18271 An Invitation to Look Although he would during his life amass a formidable collection of contemporary art, the architect Philip Cortelyou Johnson (1906–2005) chose to grace his country residence, the Glass House, with but a single seicento Old Master painting, Nicolas Poussin’s Landscape with the Burial of Phocion,2 which was This study was undertaken with the gracious cooperation of the Philip Johnson Glass House of the National Trust for Historic Preservation. Special thanks go to Dorothy Dunn of The National Trust. The author also wishes to thank Hillary Beat- tie, Steve Brosnahan, David Carrier, Daria Colombo, Wendy Katz, Eric Marcus, Jamie Romm, and Jennifer Stuart, and gratefully acknowledges the generosity of the late Richard Kuhns. -

The Umbrella Diagram Ludwig Mies Van Der Rohe, Farnsworth House

Lecture 3: Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Farnsworth House, Plano, Illinois 1946-51 The Umbrella Diagram Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Farnsworth House S. Hambright Drawing Canonical Ideas in Architecture UofA Lecture 3: Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Farnsworth House, Plano, Illinois 1946-51 “Less is more” or “Less is a bore” “Roland Barthes’s citation of ‘the boring’ as a locus of resistance…” “the Farnsworth House reveals important deviations from the modernist conventions of the open plan and the expression of structure.” Andy Warhol Campbell’s Soup Cans 1962 According to Barthes, how is ‘boring’ good? What does he mean by ‘locus of resistance.’ S. Hambright Drawing Canonical Ideas in Architecture UofA Lecture 3: Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Farnsworth House, Plano, Illinois 1946-51 Le Corbusier : Maison Dom-ino and the Maison Citrohan “…the Farnsworth House marks one of the beginnings of the breakdown of the classical part-to-whole unity of the house.” S. Hambright Drawing Canonical Ideas in Architecture UofA Lecture 3: Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Farnsworth House, Plano, Illinois 1946-51 Gerrit Rietveld: Schroeder House, Utrecht, Netherlands “…these were still single, definable entities.” S. Hambright Drawing Canonical Ideas in Architecture UofA Lecture 3: Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Farnsworth House, Plano, Illinois 1946-51 Mies van der Rohe, Concrete Country House, 1923, Germany “…these were still single, definable entities.” S. Hambright Drawing Canonical Ideas in Architecture UofA Lecture 3: Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Farnsworth House, Plano, Illinois 1946-51 Mies van der Rohe, Brick country House, 1924, Neubabelsberg, Germany “…these were still single, definable entities.” S.