CT Fairfieldco Stmarksepiscop

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Connecticut English Gardens!

7/10/2015 Weekly Real Estate Hot List: Top Ten Home & Condos | Jul 07, 2015 Toggle navigation Top Ten Lists Top Ten Florida Condo Lists Florida New Condo Developments Florida Luxury Condos Florida PreConstruction Pompano Beach Condos For Sale Weekly Hot List News Agents Say What? In The Press View All Florida Condos For Sale Connecticut English Gardens! Connecticut English Gardens! New Canaan, Connecticut, a onehour commute from Manhattan, is a town with a lot of history. Always considered one of the wealthiest enclaves in the country, that reputation started when the first rail line came through and wealthy New Yorkers started building their summer mansions there. In time, they began living in New Canaan full time and commuting to Manhattan. It was a town of tradition and all that was old world until the modern explosion took place from the 1940s through the 1960s when the Harvard Five invaded the city. Young architects Philip Johnson, Marcel Breuer, Landis Gores, John M. Johansen and Eliot Noyes ascended and began building their “outlandish” homes. Fogies were in shock and horror as houses with great expanses of glass and open floor plans began popping up. There were eighty of these new fangled houses, twenty of which have now been torn down, that put New Canaan on the architectural map. The city has since been the setting for film, books and the home base of “preppy” style. http://www.toptenrealestatedeals.com/homes/weeklytenbesthomedeals/2015/772015/3/ 1/12 7/10/2015 Weekly Real Estate Hot List: Top Ten Home & Condos | Jul 07, 2015 Now for sale is a 15,000squarefoot English Arts and Crafts/American Shinglestyle residence on 3.71 acres with English gardens, swimming pool terrace, tennis court with viewing platform and a walled children’s playground. -

Street & Number 192 Cross Ridge Road___City Or Town New

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 10024-0018 (Oct. 1990) RECEIVED 2280 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service FR 2002 National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete me '" '"'' National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item be marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable". For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer to complete all items. 1. Name of Property_________________________________________________ historic name LANDIS GORES HOUSE other names/site number N/A 2. Location street & number 192 Cross Ridge Road_________ D not for publication city or town New Canaan________________ _______ D vicinity state Connecticut code CT county Fairfield code 001 zip code .06840. 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this Kl nomination D request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property H meets D does not meet the National Register criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant DnationaJly-C§ statewide D locally.^£]J5ee continuation sheet for additional comments.) February 4, 2002 Decertifying offfoffirritle ' Date Fohn W. -

Exploring Boston's Religious History

Exploring Boston’s Religious History It is impossible to understand Boston without knowing something about its religious past. The city was founded in 1630 by settlers from England, Other Historical Destinations in popularly known as Puritans, Downtown Boston who wished to build a model Christian community. Their “city on a hill,” as Governor Old South Church Granary Burying Ground John Winthrop so memorably 645 Boylston Street Tremont Street, next to Park Street put it, was to be an example to On the corner of Dartmouth and Church, all the world. Central to this Boylston Streets Park Street T Stop goal was the establishment of Copley T Stop Burial Site of Samuel Adams and others independent local churches, in which all members had a voice New North Church (Now Saint Copp’s Hill Burying Ground and worship was simple and Stephen’s) Hull Street participatory. These Puritan 140 Hanover Street Haymarket and North Station T Stops religious ideals, which were Boston’s North End Burial Site of the Mathers later embodied in the Congregational churches, Site of Old North Church King’s Chapel Burying Ground shaped Boston’s early patterns (Second Church) Tremont Street, next to King’s Chapel of settlement and government, 2 North Square Government Center T Stop as well as its conflicts and Burial Site of John Cotton, John Winthrop controversies. Not many John Winthrop's Home Site and others original buildings remain, of Near 60 State Street course, but this tour of Boston’s “old downtown” will take you to sites important to the story of American Congregationalists, to their religious neighbors, and to one (617) 523-0470 of the nation’s oldest and most www.CongregationalLibrary.org intriguing cities. -

Miller House, Orange New Haven County, Connecticut

Henry F. Miller House, Orange New Haven County, Connecticut I, hereby certify that this property is i/ entered in the National Register __ See continuation sheet. ___ determined eligible for the National Register __ See continuation sheet. ___ determined not eligible for the National Register removed from the National Register other (explain): M______ l^ighature of Keeper Date of Action 5. Classification Ownership of Property (Check as many boxes as apply) X private __ public-local __ public-State __ public-Federal Category of Property (Check only one box) X building(s) __ district site structure object Number of Resources within Property: Contributing Noncontributing 1 ____ buildings ____ ____ sites 1 ____ structures ____ ____ objects 2 0 Total Number of contributing resources previously listed in the National Register: _0 Name of related multiple property listing: N/A 6. Function or Use Historic Functions (Enter categories from instructions) Cat: DOMESTIC_______________ Sub: ____single dwelling Current Functions (Enter categories from instructions Henry F. Miller House, Orange New Haven County, Connecticut Cat: DOMESTIC Sub: single dwelling 7. Description Architectural Classification: ___International Stvle Materials: foundation poured concrete roof built-up walls concrete block; vertical tongue and groove fir sidincr other Narrative Description Describe present and historic physical appearance, X See continuation sheet. NFS Form 10-900-a 0MB No. 1024-0018 (8-86) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES CONTINUATION SHEET Description Henry F. Miller House, Orange 7-1 New Haven County, CT Narrative Description The Henry F. Miller House is an International Style structure built in 1949 and located on a wooded hillside in the town of Orange, Connecticut. -

HOUSE...No. 13T

HOUSE... .No. 13T. fiommomutaltl) of iltnsßndjusctts. Secretary's Department Boston, March 13, 1865. Hon. Ales. H. Bullock, Speaker, Spc., Spc. Sir,—In obedience to an Order of the House of Representa- tives, passed on the 2d instant, I have the honor to transmit herewith “ the names of all corporations, with the dates of their charters, now authorized by the laws of this State to hold pro- perty in trust.” This department has no means of ascertaining how many of these corporations are now existing, and the list may therefore contain the names of many which have become extinct. Yery respectfully, Your obd’t serv’t, OLIVER WARNER, Secretary. 2 NAMES OF CORPORATIONS. [Mar. CORPORATIONS. When Incorporated. Tabernacle Church, in Salem, Oct. 27, 1781. Massachusetts Medical Society, NovT 1, 1781. Dummer Academy, Newbury, . OotT 3, 1782. Trustees of in . Congregational Parish, Norton, . Mar. 4, 1783. Boston ' . Episcopal Charitable Society, . Eeb. 12, 1784. Leicester Academy, Mar. 23, 1784. Derby School, Hingham, Nov. 11, 1784. Free School in Williamstown, Mar. 8, 1785. Scots’ Charitable Society, Boston, “ 16, 1786. “ Mass. Congregational Charitable Society, . 24, 1786. Society for Propagating the Gospel among the Indians and others in North America, Nov. 19, 1787. Congregational Society in New Salem, .... Mar. 18, 1788. Presbyterian Society in- Groton, Nov. 28, 1788. Grammar School in Roxbury, Jan. 21, 1789. “ . (Wardens, &c.,) Christ Church, Boston, . 30, 1789. Episcopal Protestant Society in Marshfield, .... June 9, 1790. Humane Society of Commonwealth of Massachusetts, . Feb. 23, 1791. First Congregational Society in Taunton, .... Mar. 8, 1791. Protestant Episcopal Society in Great Barrington, . June 18, 1791. -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. 1. Name of Property Historic name: __Norwich Mid-Century Modern Historic District_______ Other names/site number: ______________________________________ Name of related multiple property listing: _N/A__________________________________________________________ (Enter "N/A" if property is not part of a multiple property listing ____________________________________________________________________________ 2. Location Street & number: Parts of Hopson Road, Pine Tree Road, & Spring Pond Road___________ City or town: __Norwich__ State: _Vermont__ County: __Windsor__ Not For Publication: Vicinity: _____________________________________________________________________ _______ 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this nomination ___ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties -

Confronting Privilege and Possibility at SANAA's Grace Farms

The Avery Review Sam holleran – Estate of Grace: Confronting Privilege and Possibility at SANAA’s Grace Farms New Canaan, Connecticut, has long been conflated with the WASPy ur-’burb Citation: Sam Holleran, “Estate of Grace: Confronting Privilege and Possibility at SANAA’s Grace Farms,” depicted in Rick Moody’s 1994 novel-turned-film The Ice Storm: popped in The Avery Review, no. 13 (February 2016), http:// collars, monogrammed bags, and picket fences. This image has been hard to averyreview.com/issues/13/estate-of-grace. shake for this high-income town at the end of a Metro-North rail spur, which is, to be sure, a comfortable place to live—far from the clamor of New York City but close to its jobs (and also reasonably buffered from the poorer, immi- grant-heavy pockets of Fairfield County that line Interstate 95). This community of 20,000 is blessed with rolling hills, charming historic architecture, and budgets big enough for graceful living. Its outskirts are latticed with old stone walls and peppered with luxe farmhouses and grazing deer. The town’s center, or “village district,” is a compact two-block elbow of shops that hinge from the rail depot (the arterial connection to New York City’s capital flows). Their exteriors are municipally regulated by Design Guidelines mandating Colonial building styles—red brick façades with white-framed windows, low-key signage, and other “charm-enhancing” elements. [1] The result is a New Urbanist core [1] The Town of New Canaan Village District Design Guidelines “Town of New Canaan Village District that is relatively pedestrian-friendly and pleasant, if a bit stuffy. -

2009 2 March

Connecticut Preservation News March/April 2009 Volume XXXII, No. 2 C. Wigren C. courtesy of Elizabeth Mills Brown Elms on the Rebound nce upon a time, Connecticut towns and cities were It wasn’t always so. For the first European settlers, trees were graced by hundreds, even thousands, of American obstacles to be removed before they could build towns, graze O th th elm trees. By the second half of the 19 century elms had become animals, or plant crops. Only at the end of the 18 century, after a defining characteristic of New England villages, their grace- the initial clearing had been accomplished and Romanticism fully drooping branches making the streets sheltered, but still inspired a new attitude toward Nature as nurturer rather than open and inviting, corridors of space. Invariably they inspired opponent, did New Englanders begin planting trees for orna- visitors’ comments; as one Rhode Island resident remembered, ment. It began with public-spirited individuals such as James “When you came into any town in New England the landscape Hillhouse of New Haven, who initiated efforts to plant trees on changed; you entered this kind of forest with 100-foot arches. the New Haven Green and then throughout the city (actually The shadows changed. Everything seemed very reverent, there planting many of them himself, according to legend). By mid- was a certain serenity, a certain calmness… a sweetness in the air. century, village improvement societies throughout the region It was an otherworldly experience, you knew you were entering had taken up the cause, incorporating tree-planting in their an almost sacred place.” improvement programs. -

The Revs. Christian and Kristin Schmidt

The Revs. Christian and Kristin Schmidt The Revs. Christian and Kristin Schmidt are UUCB's co-ministry candidates for our senior ministry position. Their academic, professional, and denominational and community activities are detailed below. *** Kristin Grassel Schmidt Academic Bachelor of Arts, cum laude, McDaniel College (formerly Western Maryland College); General Music. May 2004 Master of Divinity, with honors, Wesley Theological Seminary. May 2010 Date of Preliminary UU Fellowship: July 15, 2010 Ordained by Cedar Lane UU Church, Bethesda, MD, March 20, 2011 Professional Interim Co-minister UU Church in Cherry Hill, NJ September 2015 – present Director of Youth Ministry UUnited Youth Ministry October 2014 – June 2015 Consulting Minister Unity Church of North Easton August 2013 – June 2015 Assistant Minister First Parish in Milton July 2012 – June 2013 Minister in Residence Church of the Larger Fellowship September 2011 – March 2012 Assistant Minister King’s Chapel, Boston September 2010 – July 2012 Summer Minister Bay Area Unitarian Universalist Church June 2010 – August 2010 Intern Minister Bay Area Unitarian Universalist Church August 2009 – May 2010 Intern Chaplain Goodwin House, Clinical Pastoral Education (CPE) Department, Alexandria, VA June – August 2009 Membership Coordinator (part-time) Cedar Lane Unitarian Universalist Church, Bethesda, MD September 2006 – June 2009 Senior Recruiting Specialist (full-time) VICCS Inc., Rockville, MD December 2005 – September 2006 Children’s Choir Director (part-time) Cedar Lane Unitarian Universalist Church, Bethesda, MD Oct 2005 – April 2006 Personnel Associate (full-time) Whitman Associates, Washington, D.C. May 2005 – Sept 2005 Denominational and Community Activities • As a youth member of Cedar Lane Unitarian Universalist Church between 1997 and 2001, served on the Youth Adult Committee, attended two General Assemblies as a voting delegate, sang in the adult choir for four years, and assisted in teaching the first grade Sunday School class. -

UUMA News the Newsletter of the Unitarian Universalist Ministers’ Association

UUMA News The Newsletter of the Unitarian Universalist Ministers’ Association November 2005—February 2006 From the President Inside this Issue: he ten members of your UUMA Executive Ministry Days/PLCC 2 T Committee (the Exec) are eager to let you know From the Editor 3 what we’ve been up to, and to learn of any concerns, From Good Offices 3 questions, or opinions you may have. And so we have a website, the UUMA chat, an email list for sending out And We Remember . 4 important news, and a quarterly newsletter. We offer each Administrator Column 7 Chapter a visit from an Exec member who will give a Sermon Awards 8 report and respond to questions and concerns. At this New UUMA Focus Group 8 year’s GA we will return to having Ministry Days (after several years of Professional Days in conjunction with The Power of Effects 9 LREDA), featuring – in addition to the CENTER presentation and worship, 50 year Address 10 including remarks by the 25- and 50-year ministers – more chances for interaction: CENTER-Fold 12 CENTER workshops; collegial conversations: a conversation with Bill Sinkford; and our annual meeting, which we expect to make more interesting starting this year. News from the Dept. of 14 Ministry & Professional Leadership And the minutes of Exec meetings are posted on our website. This only happens, though, after they have been approved at the next meeting about three months later. 25 year Address 16 To keep you more up to date, Executive Notes are now posted on the UUMA News from the UUA 17 Members’ website. -

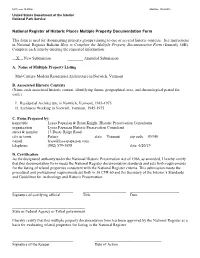

National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form

NPS Form 10-900-b OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form This form is used for documenting property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin How to Complete the Multiple Property Documentation Form (formerly 16B). Complete each item by entering the requested information. X New Submission ________ Amended Submission A. Name of Multiple Property Listing Mid-Century Modern Residential Architecture in Norwich, Vermont B. Associated Historic Contexts (Name each associated historic context, identifying theme, geographical area, and chronological period for each.) I. Residential Architecture in Norwich, Vermont, 1945-1975 II. Architects Working in Norwich, Vermont, 1945-1975 C. Form Prepared by: name/title Lyssa Papazian & Brian Knight, Historic Preservation Consultants organization Lyssa Papazian Historic Preservation Consultant street & number 13 Dusty Ridge Road city or town Putney state Vermont zip code 05346 e-mail [email protected] telephone (802) 579-3698 date 6/20/19 D. Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this documentation form meets the National Register documentation standards and sets forth requirements for the listing of related properties consistent with the National Register criteria. This submission meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR 60 and the Secretary of the Interior’s Standards and Guidelines for Archeology and Historic Preservation. _______________________________ ______________________ _________________________ Signature of certifying official Title Date _____________________________________ State or Federal Agency or Tribal government I hereby certify that this multiple property documentation form has been approved by the National Register as a basis for evaluating related properties for listing in the National Register. -

For Eleanor Heidenwith Corbett

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Tilting at Modern: Elizabeth Gordon's "The Threat to the Next America" Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/87m3z9n5 Author Corbett, Kathleen LaMoine Publication Date 2010 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Tilting at Modern: Elizabeth Gordon’s “The Threat to the Next America” By Kathleen LaMoine Corbett A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Architecture in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Andrew M. Shanken, Chair Professor Kathleen James-Chakraborty Professor Galen Cranz Professor Laurie A. Wilkie Fall 2010 Abstract Tilting at Modern: Elizabeth Gordon’s “The Threat to the Next America” by Kathleen LaMoine Corbett Doctor of Philosophy in Architecture University of California, Berkeley Professor Andrew Shanken, Chair This dissertation addresses the ways that gender, politics, and social factors were exploited and expressed in the controversy surrounding the April 1953 House Beautiful editorial, “The Threat to the Next America.” House Beautiful’s editor, Elizabeth Gordon, wrote and published this editorial as a response to ongoing institutional promotion of experimental modern residential architecture, which fell under the umbrella of the International Style, a term that came from a 1932 exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art. Gordon warned her readers that the practitioners of the International Style, which she deplored as “barren,” were designing and promoting unlivable housing. She specifically condemned German immigrant architects Walter Gropius and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, as well as French architect Le Corbusier.