NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES the PANIC of 2007 Gary B

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What Happened to the Quants in August 2007?∗

What Happened To The Quants In August 2007?∗ Amir E. Khandaniy and Andrew W. Loz First Draft: September 20, 2007 Latest Revision: September 20, 2007 Abstract During the week of August 6, 2007, a number of high-profile and highly successful quan- titative long/short equity hedge funds experienced unprecedented losses. Based on empir- ical results from TASS hedge-fund data as well as the simulated performance of a specific long/short equity strategy, we hypothesize that the losses were initiated by the rapid un- winding of one or more sizable quantitative equity market-neutral portfolios. Given the speed and price impact with which this occurred, it was likely the result of a sudden liqui- dation by a multi-strategy fund or proprietary-trading desk, possibly due to margin calls or a risk reduction. These initial losses then put pressure on a broader set of long/short and long-only equity portfolios, causing further losses on August 9th by triggering stop-loss and de-leveraging policies. A significant rebound of these strategies occurred on August 10th, which is also consistent with the sudden liquidation hypothesis. This hypothesis suggests that the quantitative nature of the losing strategies was incidental, and the main driver of the losses in August 2007 was the firesale liquidation of similar portfolios that happened to be quantitatively constructed. The fact that the source of dislocation in long/short equity portfolios seems to lie elsewhere|apparently in a completely unrelated set of markets and instruments|suggests that systemic risk in the hedge-fund industry may have increased in recent years. -

United States District Court Northern District of Illinois Eastern Division

Case: 1:05-cv-07097 Document #: 701 Filed: 04/23/07 Page 1 of 15 PageID #:<pageID> UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT NORTHERN DISTRICT OF ILLINOIS EASTERN DIVISION IN RE AMERIQUEST MORTGAGE CO. ) MORTGAGE LENDING PRACTICES ) LITIGATION ) ) ) No. 05-CV-7097 RE CONSOLIDATED CLASS ACTION ) COMPLAINT ) FOR CLAIMS OF NON-BORROWERS ) ) MEMORANDUM OPINION AND ORDER MARVIN E. ASPEN, District Court Judge: Defendants Ameriquest Mortgage Company; AMC Mortgage Services, Inc.; Town & Country Credit Corporation; Ameriquest Capital Corporation; Town & Country Title Services, Inc.; and Ameriquest Mortgage Securities, Inc. move to dismiss the borrower plaintiffs’ Consolidated Class Action Complaint in its entirety. Defendants contend that: a) plaintiffs have failed to show through “clear and specific allegations of fact” that they have standing to bring this suit; b) plaintiffs’ first cause of action, for a declaration as to their rescission rights under the Truth-in-Lending Act, 15 U.S.C. § 1601, et seq., fails because TILA rescission is not susceptible to class relief; c) plaintiffs’ second and third causes of action fail because neither the Equal Credit Opportunity Act, 15 U.S.C. § 1691, et seq., nor the Fair Credit Reporting Act, 15 U.S.C. § 1681, et seq. require notices of “adverse actions” in this case; and d) plaintiffs’ twelfth cause of action fails because California’s Civil Legal Remedies Act, Cal. Civ. Code § 1750, et seq. does not apply to the residential mortgage loans here. 1 Case: 1:05-cv-07097 Document #: 701 Filed: 04/23/07 Page 2 of 15 PageID #:<pageID> In the alternative, defendants move for a more definite statement of plaintiffs’ claims. -

Crises and Hedge Fund Risk∗

Crises and Hedge Fund Risk∗ Monica Billio†, Mila Getmansky‡, and Loriana Pelizzon§ This Draft: September 7, 2009 Abstract We study the effects of financial crises on hedge fund risk and show that liquidity, credit, equity market, and volatility are common risk factors during crises for various hedge fund strategies. We also apply a novel methodology to identify the presence of a common latent (idiosyncratic) risk factor exposure across all hedge fund strategies. If the latent risk factor is omitted in risk modeling, the resulting effect of financial crises on hedge fund risk is greatly underestimated. The common latent factor exposure across the whole hedge fund industry was present during the Long-Term Capital Management (LTCM) crisis of 1998 and the 2008 Global financial crisis. Other crises including the subprime mortgage crisis of 2007 affected the whole hedge fund industry only through classical systematic risk factors. Keywords: Hedge Funds; Risk Management; Liquidity; Financial Crises; JEL Classification: G12, G29, C51 ∗We thank Tobias Adrian, Vikas Agarwal, Lieven Baele, Nicolas Bollen, Ben Branch, Stephen Brown, Darwin Choi, Darrell Duffie, Bruno Gerard, David Hsieh, Luca Fanelli, William Fung, Patrick Gagliar- dini, Will Goetzmann, Robin Greenwood, Philipp Hartmann, Ravi Jagannathan, Nikunj Kapadia, Hossein Kazemi, Martin Lettau, Bing Liang, Andrew Lo, Narayan Naik, Colm O’Cinneide, Geert Rouwenhorst, Stephen Schaefer, Tom Schneeweis, Matthew Spiegel, Heather Tookes, Marno Verbeek, Pietro Veronesi, and seminar participants at the NBER -

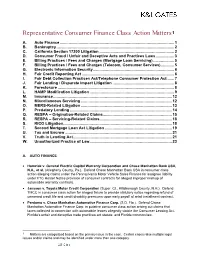

Representative Consumer Finance Class Action Matters1

Representative Consumer Finance Class Action Matters1 A. Auto Finance ........................................................................................................ 1 B. Bankruptcy ........................................................................................................... 2 C. California Section 17200 Litigation .................................................................... 2 D. Consumer Fraud / Unfair and Deceptive Acts and Practices Laws ................. 3 E. Billing Practices / Fees and Charges (Mortgage Loan Servicing) ................... 5 F. Billing Practices / Fees and Charges (Telecom, Consumer Services) ............ 5 G. Electronic Information Security .......................................................................... 6 H. Fair Credit Reporting Act .................................................................................... 6 I. Fair Debt Collection Practices Act/Telephone Consumer Protection Act ...... 7 J. Fair Lending / Disparate Impact Litigation ........................................................ 8 K. Foreclosure .......................................................................................................... 8 L. HAMP Modification Litigation ............................................................................. 9 M. Insurance ............................................................................................................ 12 N. Miscellaneous Servicing ................................................................................... 12 O. -

The Blow-Up Artist: Reporting & Essays: the New

Annals of Finance: The Blow-Up Artist: Reporting & Essays: The New ... http://www.newyorker.com/reporting/2007/10/15/071015fa_fact_cassid... ANNALS OF FINANCE THE BLOW-UP ARTIST Can Victor Niederhoffer survive another market crisis? by John Cassidy OCTOBER 15, 2007 n a wall Niederhoffer’s approach is eclectic. His funds, a friend says, appeal “to people like him: self-made people who have a maverick streak.” O opposite Victor Niederhoffer’s desk is a large painting of the Essex, a Nantucket whaling ship that sank in the South Pacific in 1820, after being attacked by a giant sperm whale, and that later served as the inspiration for “Moby-Dick.” The Essex’s captain, George Pollard, Jr., survived, and persuaded his financial backers to give him another ship, but he sailed it for little more than a year before it foundered on a coral reef. Pollard was ruined, and he ended his days as a night watchman. The painting, which Niederhoffer, a sixty-three-year-old hedge-fund manager, acquired after losing all his clients’ money—and a good deal of his own—in the Thai stock market crash of 1997, serves as an admonition against the incaution to which he, a notorious risktaker, is prone, and as a reminder of the precariousness of his success. Niederhoffer has been a professional investor for nearly three decades, during which he has made and lost several fortunes—typically by relying on methods that other traders consider reckless or unorthodox or both. In the nineteen-seventies, he wrote one of the first software programs to identify profitable trades. -

1 United States District Court District of Massachusetts

Case 1:16-cv-10482-ADB Document 70 Filed 08/01/18 Page 1 of 19 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT DISTRICT OF MASSACHUSETTS GERARD M. PENNEY and * DONNA PENNEY, * * Plaintiffs, * * v. * Civil Action No. 16-cv-10482-ADB * DEUTSCHE BANK NATIONAL TRUST * COMPANY, et al., * * Defendants. * * MEMORANDUM AND ORDER ON MOTIONS FOR SUMMARY JUDGMENT BURROUGHS, D.J. Plaintiffs Gerard M. Penney and Donna Penney initiated this lawsuit against Deutsche Bank National Trust Company as trustee of the Soundview Home Loan Trust 2005-OPT3 (“Deutsche Bank”) and Ocwen Loan Servicing, LLC (“Ocwen”) to stop a foreclosure on their home. On March 15, 2017, the Court dismissed all of the Plaintiffs’ claims in the Amended Complaint [ECF No. 21], except for the request in Count I for a declaratory judgment that the mortgage at issue is unenforceable against Donna and therefore a foreclosure cannot proceed. [ECF No. 39]. Deutsche Bank then filed counterclaims for fraud (Count I against Gerard), negligent misrepresentation (Count II against Donna), equitable subrogation (Count III against the Plaintiffs), and declaratory judgment (Count IV against the Plaintiffs). [ECF No. 55]. Currently pending before the Court are Ocwen’s motion for summary judgment on Count I of the Amended Complaint [ECF No. 57], and Deutsche Bank’s motion for partial summary judgment on Counts III and IV of the counterclaims [ECF No. 60].1 For the reasons stated below, 1 Deutsche Bank also joins Ocwen’s motion for summary judgment. [ECF Nos. 63, 64]. 1 Case 1:16-cv-10482-ADB Document 70 Filed 08/01/18 Page 2 of 19 Ocwen’s motion is DENIED and Deutsche Bank’s motion is GRANTED in part and DENIED in part. -

Hedge Funds: Due Diligence, Red Flags and Legal Liabilities

Hedge Funds: Due Diligence, Red Flags and Legal Liabilities This Website is Sponsored by: Law Offices of LES GREENBERG 10732 Farragut Drive Culver City, California 90230-4105 Tele. & Fax. (310) 838-8105 [email protected] (http://www.LGEsquire.com) BUSINESS/INVESTMENT LITIGATION/ARBITRATION ==== The following excerpts of articles, arranged mostly in chronological order and derived from the Wall Street Journal, New York Times, Reuters, Los Angles Times, Barron's, MarketWatch, Bloomberg, InvestmentNews and other sources, deal with due diligence in hedge fund investing. They describe "red flags." They discuss the hazards of trying to recover funds from failed investments. The sponsor of this website provides additional commentary. "[T]he penalties for financial ignorance have never been so stiff." --- The Ascent of Money (2008) by Niall Ferguson "Boom times are always accompanied by fraud. As the Victorian journalist Walter Bagehot put it: 'All people are most credulous when they are most happy; and when money has been made . there is a happy opportunity for ingenious mendacity.' ... Bagehot observed, loose business practices will always prevail during boom times. During such periods, the gatekeepers of the financial system -- whether bankers, professional investors, accountants, rating agencies or regulators -- should be extra vigilant. They are often just the opposite." (WSJ, 4/17/09, "A Fortune Up in Smoke") Our lengthy website contains an Index of Articles. However, similar topics, e.g., "Bayou," "Madoff," "accountant," may be scattered throughout several articles. To locate all such references, use your Adobe Reader/Acrobat "Search" tool (binocular symbol). Index of Articles: 1. "Hedge Funds Can Be Headache for Broker, As CIBC Case Shows" 2. -

Lbex-Docid 3285232 Lehman Brothers Holdings, Inc

FOIA CONFIDENTIAL TREATMENT REQUESTED BY LBEX-DOCID 3285232 LEHMAN BROTHERS HOLDINGS, INC. Agenda I FOIA CONFIDENTIAL TREATMENT REQUESTED BY LBEX-DOCID 3285232 LEHMAN BROTHERS HOLDINGS, INC. ,--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------~ Agenda Agenda • Key Themes • Risk Governance - Our Control Environment - Risk Philosophy - Committee Structures • Risk Management Overview - Risk Management Function - Risk Management Organization - External Constituents • Risk Analysis and Quantification - Risk Management Integrated Framework Risk Appetite Risk Equity Risk Appetite Usage Risk Limits • Risk Exposure • Areas of Increased Focus - Subprime Exposure - High Yield and Leveraged Loans - Hedge Funds • Conclusion • Appendix - Stress Scenarios 3 FOIA CONFIDENTIAL TREATMENT REQUESTED BY LBEX-DOCID 3285232 LEHMAN BROTHERS HOLDINGS, INC. Key Themes I FOIA CONFIDENTIAL TREATMENT REQUESTED BY LBEX-DOCID 3285232 LEHMAN BROTHERS HOLDINGS, INC. Key Themes Key Themes Risk Management is one of the core competencies of the Firm and is an intrinsic component of our control system. As a result of our focus on continuously enhancing our risk capabilities, in the current challenging environment, we feel confident that our risk position is solid. • Risk Management is at the very core of Lehman's business model - Conservative risk philosophy- supported by approximately 30% employee ownership - Effective risk governance -unwavering focus of the Executive Committee - Significant resources dedicated -

Randall Complaint

Vito Torchia, Jr. (SBN244687) 1 [email protected] BROOKSTONE LAW, PC 2 18831 Von Karman Ave., Suite 400 Irvine, CA 92612 3 Telephone: (800) 946-8655 Facsimile: (866) 257-6172 4 E-mail: [email protected] 5 Attorneys for Plaintiffs 6 7 SUPERIOR COURT OF THE STATE OF CALIFORNIA 8 COUNTY OF LOS ANGELES 9 BC526888 10 DOUGLAS RANDALL, an individual; Case No.: LOLITA RANDALL, an individual; MARK 11 COMPLAINT FOR: GENNARO, an individual; MANUEL 12 SEDILLOS, an individual; MICHELLE 1. INTENTIONAL PLACEMENT OF ROGERS, an individual; ANTONIO BORROWERS INTO DANGEROUS LOANS 13 HERNANDEZ, an individual; DONNA THEY COULD NOT AFFORD THROUGH COORDINATED DECEPTION, IN THE NAME 14 HERNANDEZ, an individual; LAURO OF MAXIMIZING LOAN VOLUME AND THUS ROBERTO, an individual; AMALIA PROFIT 15 ROBERTO, an individual; VINCENT COUNTl-FRAUDULENTCONCEALMENT LOMBARDO, an individual; LORRAINE 16 LOMBARDO, an individual; SHIRLEY COUNT 2- INTENTIONAL MISREPRESENTATION 17 COFFEY, an individual; DINA GARAY, an individual; JAMES FORTIER, an COUNT 3- NEGLIGENT MISREPRESENTATION 18 individual; ANGEL DIAZ, an individual; COUNT 4- NEGLIGENCE ALICE SHIOTSUGU, an individual; 19 VICENTE PINEDA, an individual; JERRY COUNT 5- UNFAIR, UNLAWFUL, AND FRAUDULENT BUSINESS PRACTICES 20 ROGGE, an individual; MICHAEL (VIOLATION OF CAL. BUS. & PROF. CODE SHAFFER, an individual; VICTORIA §17200) 21 ARCADI, an individual; DEBORAH 2; INDIVIDUAL APPRAISAL INFLATION BECKER, an individual; YOUSEF 22 LAZARIAN, an individual; LINAT COUNT 6- INTENTIONAL 23 LAZARIAN, an individual; DIANA MISREPRESENTATION BOGDEN, an individual; SHILA COUNT 7-NEGLIGENTMISREPRESENTATION 24 ARDALAN, an individual; GEORGE COUNT 8- NEGLIGENCE 25 CHRIPCZUK, an individual; ROBERT ORNELAS, an individual; LICET COUNT 9- UNFAIR, UNLAWFUL, AND FRAUDULENT BUSINESS PRACTICES ORNELAS, an individual; AMIE GA YE, an 26 (VIOLATION OF CAL. -

The Causes of Fraud in Financial Crises: Evidence from the Mortgage-Backed Securities Industry

IRLE IRLE WORKING PAPER #122-15 October 2015 The Causes of Fraud in Financial Crises: Evidence from the Mortgage-Backed Securities Industry Neil Fligstein and Alexander Roehrkasse Cite as: Neil Fligstein and Alexander Roehrkasse (2015). “The Causes of Fraud in Financial Crises: Evidence from the Mortgage-Backed Securities Industry”. IRLE Working Paper No. 122-15. http://irle.berkeley.edu/workingpapers/122-15.pdf irle.berkeley.edu/workingpapers FRAUD IN FINANCIAL CRISES The Causes of Fraud in Financial Crises: Evidence from the Mortgage-Backed Securities Industry* Neil Fligstein Alexander Roehrkasse University of California–Berkeley Key words: white-collar crime; finance; organizations; markets. * Corresponding author: Neil Fligstein, Department of Sociology, 410 Barrows Hall, University of California– Berkeley, Berkeley, CA, 94720-1980. Email: [email protected]. We thank Ogi Radic for excellent research assistance, and Diane Vaughan, Cornelia Woll, and participants of conferences and workshops at Yale Law School, Sciences Po, the German Historical Society, and the University of California–Berkeley for helpful comments. Roehrkasse acknowledges support by the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship under Grant No. DGE 1106400. All remaining errors are our own. FRAUD IN FINANCIAL CRISES ABSTRACT The financial crisis of 2007-2009 was marked by widespread fraud in the mortgage securitization industry. Most of the largest mortgage originators and mortgage-backed securities issuers and underwriters have been implicated in regulatory settlements, and many have paid multibillion-dollar penalties. This paper seeks to explain why this behavior became so pervasive. We evaluate predominant theories of white-collar crime, finding that those emphasizing deregulation or technical opacity identify only necessary, not sufficient conditions. -

Rescindedocc Bulletin

OCC Bulletin 2009-7 Page 1 of 2 OCC 2009-7 RESCINDEDOCC BULLETIN Comptroller of the Currency Administrator of National Banks Final Rule for Home Ownership and Equity Subject: Truth in Lending Act Description: Protection Act Amendments Date: February 19, 2009 TO: Chief Executive Officers and Compliance Officers of All National Banks and National Bank Operating Subsidiaries, Department and Division Heads, and All Examining Personnel The Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System published in the July 30, 2008, Federal Register, amendments to Regulation Z under the Home Ownership and Equity Protection Act (HOEPA). The final rule is intended to protect consumers from unfair, deceptive, or abusive acts and practices in mortgage lending and to restrict certain mortgage practices. Higher-Priced Mortgage Loans1 The four key protections of the newly defined category of “higher-priced mortgage loans” for loans secured by a consumer’s principal dwelling will Prohibit a lender from making a loan without regard to the borrower’s ability to repay the loan from income and assets other than the home’s value; Require creditors to verify the income and assets they rely upon to determine repayment ability; Ban any prepayment penalties if the payment can change in the initial four years and, for other higher-priced mortgages, restrict the prepayment penalty period to no more than two years; and Require creditors to establish escrow accounts for property taxes and homeowner’s insurance for first-lien higher-priced mortgage loans. All Loans Secured by a Consumer’s Principal Dwelling In addition, the rules adopt the following protections for all loans secured by a consumer’s principal dwelling though it may not be classified as a higher-priced mortgage: OCC Bulletin 2009-7 Page 2 of 2 Creditors and mortgage brokers are prohibited from coercing a real estate appraiser to misstate a home’s value. -

Legal County Journal Erie

Erie County Legal November 8, 2013 Journal Vol. 96 No. 45 USPS 178-360 96 ERIE - 1 - Erie County Legal Journal Reporting Decisions of the Courts of Erie County The Sixth Judicial District of Pennsylvania Managing Editor: Heidi M. Weismiller PLEASE NOTE: NOTICES MUST BE RECEIVED AT THE ERIE COUNTY BAR ASSOCIATION OFFICE BY 3:00 P.M. THE FRIDAY PRECEDING THE DATE OF PUBLICATION. All legal notices must be submitted in typewritten form and are published exactly as submitted by the advertiser. The Erie County Bar Association will not assume any responsibility to edit, make spelling corrections, eliminate errors in grammar or make any changes in content. The Erie County Legal Journal makes no representation as to the quality of services offered by an advertiser in this publication. Advertisements in the Erie County Legal Journal do not constitute endorsements by the Erie County Bar Association of the parties placing the advertisements or of any product or service being advertised. INDEX NOTICE TO THE PROFESSION ................................................................... 4 COURT OF COMMON PLEAS Certifi cate of Authority Notice ........................................................................ 5 Change of Name Notice .................................................................................. 5 Dissolution Notices .......................................................................................... 5 Incorporation Notices ....................................................................................... 5 Legal Notice