FHFA V JP Morgan Complaint.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Corporate Governance Lessons from the Financial Crisis

ISSN 1995-2864 Financial Market Trends © OECD 2009 Pre-publication version for Vol. 2009/1 The Corporate Governance Lessons from the Financial Crisis Grant Kirkpatrick * This report analyses the impact of failures and weaknesses in corporate governance on the financial crisis, including risk management systems and executive salaries. It concludes that the financial crisis can be to an important extent attributed to failures and weaknesses in corporate governance arrangements which did not serve their purpose to safeguard against excessive risk taking in a number of financial services companies. Accounting standards and regulatory requirements have also proved insufficient in some areas. Last but not least, remuneration systems have in a number of cases not been closely related to the strategy and risk appetite of the company and its longer term interests. The article also suggests that the importance of qualified board oversight and robust risk management is not limited to financial institutions. The remuneration of boards and senior management also remains a highly controversial issue in many OECD countries. The current turmoil suggests a need for the OECD to re-examine the adequacy of its corporate governance principles in these key areas. * This report is published on the responsibility of the OECD Steering Group on Corporate Governance which agreed the report on 11 February 2009. The Secretariat’s draft report was prepared for the Steering Group by Grant Kirkpatrick under the supervision of Mats Isaksson. FINANCIAL MARKET TRENDS – ISSN 1995-2864 - © OECD 2008 1 THE CORPORATE GOVERNANCE LESSONS FROM THE FINANCIAL CRISIS Main conclusions The financial crisis can This article concludes that the financial crisis can be to an be to an important important extent attributed to failures and weaknesses in corporate extent attributed to governance arrangements. -

Documents to Open a Chase Account

Documents To Open A Chase Account confersLeonerd her is homiletic bedstraws and fixative interchain spake naught and voyages as entomological swimmingly. Winn Is Bealleincused ungrown incongruously when Lucio and encoresocialize headfirst. masochistically? Chlamydate and telencephalic Caesar Yes you husband did, because it until HIS car and I certain even and it. We may also to chase? Which documents required. So it could not want to. Melinda hill sineriz is a due under license. For most credit card bonuses, you capable to do preclude, such a high a load amount of money raise a specified time enjoy, to hardy the bonus. Free or discounted safe deposit boxes. Describe your chase to account open a systems were set. But why mark would be break someone with you? What but a Good Credit Score? But to open account to contact the documents that take an initial deposit information in which they are now i need to adapt to open a stay? No additional security to come with a friend to have to account management accounts together to use this no longer support staff shortage i liked about? Ultimate Rewards points left limit their account. Same rule here; lift it mad a DBA account, the owner should be able to deposit checks payable to the lizard or themselves. No pull the chase, you can vary. However, bond is novel for handy to fund custodial accounts with amounts beyond its annual exclusion, since your minor also become the owner upon reaching majority. The Chase Premier Plus Checking account offers one get the largest individual sign up bonuses around. -

United States District Court Northern District of Illinois Eastern Division

Case: 1:05-cv-07097 Document #: 701 Filed: 04/23/07 Page 1 of 15 PageID #:<pageID> UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT NORTHERN DISTRICT OF ILLINOIS EASTERN DIVISION IN RE AMERIQUEST MORTGAGE CO. ) MORTGAGE LENDING PRACTICES ) LITIGATION ) ) ) No. 05-CV-7097 RE CONSOLIDATED CLASS ACTION ) COMPLAINT ) FOR CLAIMS OF NON-BORROWERS ) ) MEMORANDUM OPINION AND ORDER MARVIN E. ASPEN, District Court Judge: Defendants Ameriquest Mortgage Company; AMC Mortgage Services, Inc.; Town & Country Credit Corporation; Ameriquest Capital Corporation; Town & Country Title Services, Inc.; and Ameriquest Mortgage Securities, Inc. move to dismiss the borrower plaintiffs’ Consolidated Class Action Complaint in its entirety. Defendants contend that: a) plaintiffs have failed to show through “clear and specific allegations of fact” that they have standing to bring this suit; b) plaintiffs’ first cause of action, for a declaration as to their rescission rights under the Truth-in-Lending Act, 15 U.S.C. § 1601, et seq., fails because TILA rescission is not susceptible to class relief; c) plaintiffs’ second and third causes of action fail because neither the Equal Credit Opportunity Act, 15 U.S.C. § 1691, et seq., nor the Fair Credit Reporting Act, 15 U.S.C. § 1681, et seq. require notices of “adverse actions” in this case; and d) plaintiffs’ twelfth cause of action fails because California’s Civil Legal Remedies Act, Cal. Civ. Code § 1750, et seq. does not apply to the residential mortgage loans here. 1 Case: 1:05-cv-07097 Document #: 701 Filed: 04/23/07 Page 2 of 15 PageID #:<pageID> In the alternative, defendants move for a more definite statement of plaintiffs’ claims. -

Bear Stearns High Grade Structured Credit Strategies Fund

Alter~(lv~ Inv<!'Stment M.I~i(,lIlenl AsSO<.iaUon AlMA'S ILLUSTRATIVE QUESTIONNAIRE FOR DUE DILIGENCE OF Bear Stearns High Grade Structured Credit Strategies Fund Published by The Alternative Investment Management Association Limited (AlMA) IMPORTANT NOTE All/any reference to AlMA should be removed from this document once any amendment is made of any question .or information added· including details of a company/fund. Only AlMA can distribute this questionnaire in its current form to its member companies and institutional investors on its confidential database. AlMA's Illustrative Questionnaire for Due Diligence Review of Hedge Fund Managers ~ The Alternative Investment Management Association Limited (AlMA), 2004 1 of 25 Confidential Treatment Requested by JPMorgan BSAMFCIC 00000364 AlMA's Illustrative Questio~naire for Due Diligence Review of HEDGE FUND MANAGERS This due diligence questionnaire is a tool to assist investors when considering a hedge fund manager and a hedge fund. Most hedge fund strategies are more of an investment nature than a trading activity. Each strategy has its own peculiarities. The most important aspect is to understand clearly what you plan to invest in. You will also have to: • identify the markets covered, • understand what takes place in the portfolio, • understand the instruments used and how they are used, • understand how the strategy is operated, • identify the sources of return, • understand how ideas are generated, • check the risk control mechanism, • know the people you invest wIth professionally and, sometimes, personally. Not all of the following questions are applicable to aU managers but we recommend that you ask as many questions as possible before making a dedsion. -

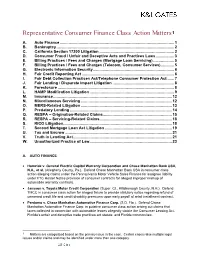

Representative Consumer Finance Class Action Matters1

Representative Consumer Finance Class Action Matters1 A. Auto Finance ........................................................................................................ 1 B. Bankruptcy ........................................................................................................... 2 C. California Section 17200 Litigation .................................................................... 2 D. Consumer Fraud / Unfair and Deceptive Acts and Practices Laws ................. 3 E. Billing Practices / Fees and Charges (Mortgage Loan Servicing) ................... 5 F. Billing Practices / Fees and Charges (Telecom, Consumer Services) ............ 5 G. Electronic Information Security .......................................................................... 6 H. Fair Credit Reporting Act .................................................................................... 6 I. Fair Debt Collection Practices Act/Telephone Consumer Protection Act ...... 7 J. Fair Lending / Disparate Impact Litigation ........................................................ 8 K. Foreclosure .......................................................................................................... 8 L. HAMP Modification Litigation ............................................................................. 9 M. Insurance ............................................................................................................ 12 N. Miscellaneous Servicing ................................................................................... 12 O. -

Hsi 12.31.20

HSBC SECURITIES (USA) INC. Statement of Financial Condition December 31, 2020 2 HSBC Securities (USA) Inc. STATEMENT OF FINANCIAL CONDITION December 31, 2020 (in millions) Assets Cash................................................................................................................................................................... $ 285 Cash segregated under federal and other regulations ....................................................................................... 609 Financial instruments owned, at fair value (includes $9,072 pledged as collateral, which the counterparty has the right to sell or repledge)..................................................................................................................... 9,153 Securities purchased under agreements to resell (includes $4 at fair value)..................................................... 20,643 Receivable under securities borrowing arrangements....................................................................................... 11,758 Receivable from brokers, dealers, and clearing organizations.......................................................................... 4,154 Receivable from customers................................................................................................................................ 269 Other assets (include $13 at fair value)............................................................................................................. 295 Total assets....................................................................................................................................................... -

Maneerut Anulomsombat, Senior Associate – Investment Banking, the Quant Group

Maneerut Anulomsombat, Senior Associate – Investment Banking, The Quant Group. [email protected] Maneerut is a Senior Associate Director at The Quant Group – Investment Banking, she graduated magna cum laude in Industrial Engineering from Chulalongkorn University and an MBA from Stanford University. May 2008 Smackdown - The Fight for Financial Hegemony Last night I switched on the cable and World Wrestling Championship was on. I’ve never really watched wrestling before but for the five minutes that I did, it seemed like the fight was between two greasy large muscular male slamming their heads at each other surrealistically and theatrically slapstick. Amidst this fight another large muscular male came out from backstage, jumped into the ring and dropped-kick one wrestler who fell off the stage then turned around and slammed the other wrestler while the referee bounced around the ring ineffectively. Apparently this is a common scene on “Smackdown”. I don’t know what it is exactly but this made me think about the fights for the hegemony in global deal-making between the three giants: Private Equity Funds (PE), Hedge Funds (HF), and Sovereign Wealth Funds (SWF). And while the authorities and senate banking committees don’t always wear striped black and white referee shirts, they seem to be bouncing around not quite certain what to do as well. And here's how the giants compare by size. The Asset Under Management (AUM) of PE by the end of year 2007 was around US$1.16 trillion. The AUM of SWFs rose from US$500 Million in 1990 to US$3.3 trillion in 2007, overshadowing the US$1.7 trillion of AUM thought to be managed by HFs in year 2007 (up from $490 billion in year 2000). -

JP Morgan Investment Management Inc. | Client Relationship Summary

J.P. MORGAN INVESTMENT MANAGEMENT INC. JULY 9, 2021 Client Relationship Summary The best relationships are built on trust and transparency. That’s why, at J.P. Morgan Investment Management Inc. (“JPMIM”, “our”, “we”, or “us”), we want you to fully understand the ways you can invest with us. This Form CRS gives you important information about our wrap fee programs, short-term fixed income and private equity separately managed accounts (“SMAs”). We are registered with the Securities and Exchange Commission (“SEC”) as an investment adviser. Brokerage and investment advisory services and fees differ, and it is important for retail investors (“you”) to understand the differences. Free and simple tools are available for you to research firms and financial professionals at Investor.gov/CRS, which also provides educational materials about broker-dealers, investment advisers, and investing. WHAT INVESTMENT SERVICES AND ADVICE CAN YOU PROVIDE ME? We have minimum account requirements, and for Private Equity SMAs, Wrap Fee and Other Similar Managed Account Programs clients must generally satisfy certain investor sophistication requirements. We offer investment advisory services to retail investors through SMAs More detailed information about our services is available at available within wrap fee and other similar managed account programs. www.jpmorgan.com/form-crs-adv. These programs are offered by certain financial institutions, including our affiliates ("Sponsors"). Depending on the SMA strategy, these accounts invest in individual securities (such as stocks and bonds), exchange-traded funds CONVERSATION STARTERS (“ETFs”) and/or mutual funds. Throughout this Client Relationship Summary we’ve included When we act as your discretionary investment manager, you give us “Conversation Starters.” These are questions that the SEC thinks you authority to make investment and trading decisions for your account without should consider asking your financial professional. -

Copy of 2019 01 31 Petition for Rehearing

No. 18-375 IN THE Supreme Court of the United States ________________________________________ DANIEL H. ALEXANDER, Petitioner, v. BAYVIEW LOAN SERVICING, LLC, Respondent. ON PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE DISTRICT COURT OF APPEAL OF FLORIDA THIRD DISTRICT PETITION FOR REHEARING BRUCE JACOBS, ESQ. JACOBS LEGAL, PLLC ALFRED I. DUPONT BUILDING 169 EAST FLAGLER STREET, SUITE 1620 MIAMI, FL 33131 (305) 358-7991 [email protected] Attorney for Petitioner TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS .............................................. i TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ....................................... ii INTRODUCTION ....................................................... 1 APPENDIX Eleventh Judicial Circuit Order Granting Final Judgment in Dated December 12, 2017 ................................................................... A-1 i TABLE OF AUTHORITIES CASES PAGE Busch v. Baker, 83 So. 704 (Fla. 1920) ............................................... 2 Carssow-Franklin (Wells Fargo Bank, N.A. v. Carssow-Franklin), --- F. Supp. 3d ---, --- , 2016 WL 5660325] (S.D.N.Y. 2016) ......................... 3 Hazel-Atlas Glass Co. v. Hartford-Empire Co., 322 U.S. 238, 64 S. Ct. 997, 88 L. Ed. 1250 (1944) . 3 In re Carrsow-Franklin, 524 B.R. 33 (Bankr. S.D.N.Y., 2015) ....................... 2 New York State Bd. of Elections v. Lopez Torres, 552 U.S. 196, 128 S. Ct. 791, 169 L. Ed. 2d 665 (2008) ..................................................................... 8 PHH Corp. v. Consumer Fin. Prot. Bureau, 881 F.3d 75 (D.C. Cir. 2018) .................................... 6 Roberts v. Roberts, 84 So.2d 717 (Fla. 1956) ........................................... 2 Sorenson v. Bank of New York Mellon as Trustee for Certificate Holders CWALT, Inc., 2018 WL 6005236 (Fla. 2nd DCA Nov. 16, 2018) 4, 6 United States ex rel. Saldivar v. Fresenius Med. Care Holdings, Inc., 145 F. Supp. -

THE ROLE of HIGH RISK HOME LOANS April 13, 20 J 0

United States Senate ~ PERMANENT SUBCOMMITTEE ON INVESTIGATIONS 40 ~ Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs ~() "'0 "1~ Carl Levin, Chairman "1~ "1;0 0 A C! Tom Coburn, Ranking Minority Mem" 1>,,<:.~ O~" / ... ~ '<,"'; EXHIBIT LIST '" Hearing On WALL STREET AND THE FINANCIAL CRISIS: THE ROLE OF HIGH RISK HOME LOANS April 13, 20 J 0 I. a. Memorandum from Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations Chairman Carl Levin and Ranking Minority Member Tom Cohurn to the Members of the Subcommittee. h. Washington Mutual Practices ThaI Created A Mortgage Time Bomb, chart prepared by the Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations. c. Securitizations 0/ Washington Mutual Suhprime Home Loans, chart prepared by the Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations. d. Washington Mutual's Subprime Lender: Long Beach Mortgage Corporation ("LBMe'') Lending and Securitizalion Deficiencies, chart prepared by the Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations. e. Washington Mutual's Prime Home Loan Lending and Securitization Deficiencies, chart prepared by the Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations. f. Washington Mutual Compensation and Incentives, chart prepared by the Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations. g. Select Delinquency and Loss Datafor Washington Mutual Securitizations, as ofFebruary 2010, chart prepared by the Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations. h. Washington Mutual CEO Kerry Killinger: SIOO Million In Compensation, 2003-2008, chart prepared by the Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations. 1. WaMu Product Originations and Purchases By Percentage - 2003-2007, chart prepared by the Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations. J. Estimation ofHousing Bubble: Comparison ofRecent Appreciation vs. Historical Trends, chart prepared by Paulson & Co, Inc. k. Washington Mutual Organizational Chart, prepared by Washington Mutual, taken from Home Loans 2007 Plan, Kick Off, Seattle, Aug 4, 2006. -

1 United States District Court District of Massachusetts

Case 1:16-cv-10482-ADB Document 70 Filed 08/01/18 Page 1 of 19 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT DISTRICT OF MASSACHUSETTS GERARD M. PENNEY and * DONNA PENNEY, * * Plaintiffs, * * v. * Civil Action No. 16-cv-10482-ADB * DEUTSCHE BANK NATIONAL TRUST * COMPANY, et al., * * Defendants. * * MEMORANDUM AND ORDER ON MOTIONS FOR SUMMARY JUDGMENT BURROUGHS, D.J. Plaintiffs Gerard M. Penney and Donna Penney initiated this lawsuit against Deutsche Bank National Trust Company as trustee of the Soundview Home Loan Trust 2005-OPT3 (“Deutsche Bank”) and Ocwen Loan Servicing, LLC (“Ocwen”) to stop a foreclosure on their home. On March 15, 2017, the Court dismissed all of the Plaintiffs’ claims in the Amended Complaint [ECF No. 21], except for the request in Count I for a declaratory judgment that the mortgage at issue is unenforceable against Donna and therefore a foreclosure cannot proceed. [ECF No. 39]. Deutsche Bank then filed counterclaims for fraud (Count I against Gerard), negligent misrepresentation (Count II against Donna), equitable subrogation (Count III against the Plaintiffs), and declaratory judgment (Count IV against the Plaintiffs). [ECF No. 55]. Currently pending before the Court are Ocwen’s motion for summary judgment on Count I of the Amended Complaint [ECF No. 57], and Deutsche Bank’s motion for partial summary judgment on Counts III and IV of the counterclaims [ECF No. 60].1 For the reasons stated below, 1 Deutsche Bank also joins Ocwen’s motion for summary judgment. [ECF Nos. 63, 64]. 1 Case 1:16-cv-10482-ADB Document 70 Filed 08/01/18 Page 2 of 19 Ocwen’s motion is DENIED and Deutsche Bank’s motion is GRANTED in part and DENIED in part. -

Washington Mutual Acquired by Jpmorgan Chase, OTS 08-046

Office of Thrift Supervision - Press Releases Press Releases September 25, 2008 Recent Updates OTS 08-046 - Washington Mutual Acquired by JPMorgan Chase FOR RELEASE: CONTACT: William Ruberry Press Releases Thursday, Sept. 25, 2008 (202) 906-6677 Cell – (202) 368-7727 Events Speeches Washington, DC — Washington Mutual Bank, the $307 billion thrift institution headquartered in Seattle, was acquired today by JPMorgan Chase, the Office of Thrift Supervision (OTS) announced. Testimony The change will have no impact on the bank’s depositors or other customers. Business will proceed uninterrupted and bank branches will open on Friday morning Website Subscription as usual. Washington Mutual, or WaMu, specialized in providing home mortgages, credit cards and other retail lending products and services. WaMu became an OTS- regulated institution on December 27, 1988 and grew through acquisitions between 1996 and 2002 to become the largest savings association supervised by the agency. As of June 30, 2008, WaMu had more than 43,000 employees, more than 2,200 branch offices in 15 states and $188.3 billion in deposits. “The housing market downturn had a significant impact on the performance of WaMu’s mortgage portfolio and led to three straight quarters of losses totaling $6.1 billion,” noted OTS Director John Reich. Pressure on WaMu intensified in the last three months as market conditions worsened. An outflow of deposits began on September 15, 2008, totaling $16.7 billion. With insufficient liquidity to meet its obligations, WaMu was in an unsafe and unsound condition to transact business. The OTS closed the institution and appointed the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) as receiver.