Q:\1-06-Cv-828 Order on Summary Judgment Motions.Wpd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

United States District Court Northern District of Illinois Eastern Division

Case: 1:05-cv-07097 Document #: 701 Filed: 04/23/07 Page 1 of 15 PageID #:<pageID> UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT NORTHERN DISTRICT OF ILLINOIS EASTERN DIVISION IN RE AMERIQUEST MORTGAGE CO. ) MORTGAGE LENDING PRACTICES ) LITIGATION ) ) ) No. 05-CV-7097 RE CONSOLIDATED CLASS ACTION ) COMPLAINT ) FOR CLAIMS OF NON-BORROWERS ) ) MEMORANDUM OPINION AND ORDER MARVIN E. ASPEN, District Court Judge: Defendants Ameriquest Mortgage Company; AMC Mortgage Services, Inc.; Town & Country Credit Corporation; Ameriquest Capital Corporation; Town & Country Title Services, Inc.; and Ameriquest Mortgage Securities, Inc. move to dismiss the borrower plaintiffs’ Consolidated Class Action Complaint in its entirety. Defendants contend that: a) plaintiffs have failed to show through “clear and specific allegations of fact” that they have standing to bring this suit; b) plaintiffs’ first cause of action, for a declaration as to their rescission rights under the Truth-in-Lending Act, 15 U.S.C. § 1601, et seq., fails because TILA rescission is not susceptible to class relief; c) plaintiffs’ second and third causes of action fail because neither the Equal Credit Opportunity Act, 15 U.S.C. § 1691, et seq., nor the Fair Credit Reporting Act, 15 U.S.C. § 1681, et seq. require notices of “adverse actions” in this case; and d) plaintiffs’ twelfth cause of action fails because California’s Civil Legal Remedies Act, Cal. Civ. Code § 1750, et seq. does not apply to the residential mortgage loans here. 1 Case: 1:05-cv-07097 Document #: 701 Filed: 04/23/07 Page 2 of 15 PageID #:<pageID> In the alternative, defendants move for a more definite statement of plaintiffs’ claims. -

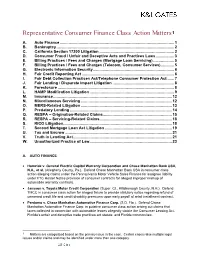

Representative Consumer Finance Class Action Matters1

Representative Consumer Finance Class Action Matters1 A. Auto Finance ........................................................................................................ 1 B. Bankruptcy ........................................................................................................... 2 C. California Section 17200 Litigation .................................................................... 2 D. Consumer Fraud / Unfair and Deceptive Acts and Practices Laws ................. 3 E. Billing Practices / Fees and Charges (Mortgage Loan Servicing) ................... 5 F. Billing Practices / Fees and Charges (Telecom, Consumer Services) ............ 5 G. Electronic Information Security .......................................................................... 6 H. Fair Credit Reporting Act .................................................................................... 6 I. Fair Debt Collection Practices Act/Telephone Consumer Protection Act ...... 7 J. Fair Lending / Disparate Impact Litigation ........................................................ 8 K. Foreclosure .......................................................................................................... 8 L. HAMP Modification Litigation ............................................................................. 9 M. Insurance ............................................................................................................ 12 N. Miscellaneous Servicing ................................................................................... 12 O. -

1 United States District Court District of Massachusetts

Case 1:16-cv-10482-ADB Document 70 Filed 08/01/18 Page 1 of 19 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT DISTRICT OF MASSACHUSETTS GERARD M. PENNEY and * DONNA PENNEY, * * Plaintiffs, * * v. * Civil Action No. 16-cv-10482-ADB * DEUTSCHE BANK NATIONAL TRUST * COMPANY, et al., * * Defendants. * * MEMORANDUM AND ORDER ON MOTIONS FOR SUMMARY JUDGMENT BURROUGHS, D.J. Plaintiffs Gerard M. Penney and Donna Penney initiated this lawsuit against Deutsche Bank National Trust Company as trustee of the Soundview Home Loan Trust 2005-OPT3 (“Deutsche Bank”) and Ocwen Loan Servicing, LLC (“Ocwen”) to stop a foreclosure on their home. On March 15, 2017, the Court dismissed all of the Plaintiffs’ claims in the Amended Complaint [ECF No. 21], except for the request in Count I for a declaratory judgment that the mortgage at issue is unenforceable against Donna and therefore a foreclosure cannot proceed. [ECF No. 39]. Deutsche Bank then filed counterclaims for fraud (Count I against Gerard), negligent misrepresentation (Count II against Donna), equitable subrogation (Count III against the Plaintiffs), and declaratory judgment (Count IV against the Plaintiffs). [ECF No. 55]. Currently pending before the Court are Ocwen’s motion for summary judgment on Count I of the Amended Complaint [ECF No. 57], and Deutsche Bank’s motion for partial summary judgment on Counts III and IV of the counterclaims [ECF No. 60].1 For the reasons stated below, 1 Deutsche Bank also joins Ocwen’s motion for summary judgment. [ECF Nos. 63, 64]. 1 Case 1:16-cv-10482-ADB Document 70 Filed 08/01/18 Page 2 of 19 Ocwen’s motion is DENIED and Deutsche Bank’s motion is GRANTED in part and DENIED in part. -

Randall Complaint

Vito Torchia, Jr. (SBN244687) 1 [email protected] BROOKSTONE LAW, PC 2 18831 Von Karman Ave., Suite 400 Irvine, CA 92612 3 Telephone: (800) 946-8655 Facsimile: (866) 257-6172 4 E-mail: [email protected] 5 Attorneys for Plaintiffs 6 7 SUPERIOR COURT OF THE STATE OF CALIFORNIA 8 COUNTY OF LOS ANGELES 9 BC526888 10 DOUGLAS RANDALL, an individual; Case No.: LOLITA RANDALL, an individual; MARK 11 COMPLAINT FOR: GENNARO, an individual; MANUEL 12 SEDILLOS, an individual; MICHELLE 1. INTENTIONAL PLACEMENT OF ROGERS, an individual; ANTONIO BORROWERS INTO DANGEROUS LOANS 13 HERNANDEZ, an individual; DONNA THEY COULD NOT AFFORD THROUGH COORDINATED DECEPTION, IN THE NAME 14 HERNANDEZ, an individual; LAURO OF MAXIMIZING LOAN VOLUME AND THUS ROBERTO, an individual; AMALIA PROFIT 15 ROBERTO, an individual; VINCENT COUNTl-FRAUDULENTCONCEALMENT LOMBARDO, an individual; LORRAINE 16 LOMBARDO, an individual; SHIRLEY COUNT 2- INTENTIONAL MISREPRESENTATION 17 COFFEY, an individual; DINA GARAY, an individual; JAMES FORTIER, an COUNT 3- NEGLIGENT MISREPRESENTATION 18 individual; ANGEL DIAZ, an individual; COUNT 4- NEGLIGENCE ALICE SHIOTSUGU, an individual; 19 VICENTE PINEDA, an individual; JERRY COUNT 5- UNFAIR, UNLAWFUL, AND FRAUDULENT BUSINESS PRACTICES 20 ROGGE, an individual; MICHAEL (VIOLATION OF CAL. BUS. & PROF. CODE SHAFFER, an individual; VICTORIA §17200) 21 ARCADI, an individual; DEBORAH 2; INDIVIDUAL APPRAISAL INFLATION BECKER, an individual; YOUSEF 22 LAZARIAN, an individual; LINAT COUNT 6- INTENTIONAL 23 LAZARIAN, an individual; DIANA MISREPRESENTATION BOGDEN, an individual; SHILA COUNT 7-NEGLIGENTMISREPRESENTATION 24 ARDALAN, an individual; GEORGE COUNT 8- NEGLIGENCE 25 CHRIPCZUK, an individual; ROBERT ORNELAS, an individual; LICET COUNT 9- UNFAIR, UNLAWFUL, AND FRAUDULENT BUSINESS PRACTICES ORNELAS, an individual; AMIE GA YE, an 26 (VIOLATION OF CAL. -

The Causes of Fraud in Financial Crises: Evidence from the Mortgage-Backed Securities Industry

IRLE IRLE WORKING PAPER #122-15 October 2015 The Causes of Fraud in Financial Crises: Evidence from the Mortgage-Backed Securities Industry Neil Fligstein and Alexander Roehrkasse Cite as: Neil Fligstein and Alexander Roehrkasse (2015). “The Causes of Fraud in Financial Crises: Evidence from the Mortgage-Backed Securities Industry”. IRLE Working Paper No. 122-15. http://irle.berkeley.edu/workingpapers/122-15.pdf irle.berkeley.edu/workingpapers FRAUD IN FINANCIAL CRISES The Causes of Fraud in Financial Crises: Evidence from the Mortgage-Backed Securities Industry* Neil Fligstein Alexander Roehrkasse University of California–Berkeley Key words: white-collar crime; finance; organizations; markets. * Corresponding author: Neil Fligstein, Department of Sociology, 410 Barrows Hall, University of California– Berkeley, Berkeley, CA, 94720-1980. Email: [email protected]. We thank Ogi Radic for excellent research assistance, and Diane Vaughan, Cornelia Woll, and participants of conferences and workshops at Yale Law School, Sciences Po, the German Historical Society, and the University of California–Berkeley for helpful comments. Roehrkasse acknowledges support by the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship under Grant No. DGE 1106400. All remaining errors are our own. FRAUD IN FINANCIAL CRISES ABSTRACT The financial crisis of 2007-2009 was marked by widespread fraud in the mortgage securitization industry. Most of the largest mortgage originators and mortgage-backed securities issuers and underwriters have been implicated in regulatory settlements, and many have paid multibillion-dollar penalties. This paper seeks to explain why this behavior became so pervasive. We evaluate predominant theories of white-collar crime, finding that those emphasizing deregulation or technical opacity identify only necessary, not sufficient conditions. -

Rescindedocc Bulletin

OCC Bulletin 2009-7 Page 1 of 2 OCC 2009-7 RESCINDEDOCC BULLETIN Comptroller of the Currency Administrator of National Banks Final Rule for Home Ownership and Equity Subject: Truth in Lending Act Description: Protection Act Amendments Date: February 19, 2009 TO: Chief Executive Officers and Compliance Officers of All National Banks and National Bank Operating Subsidiaries, Department and Division Heads, and All Examining Personnel The Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System published in the July 30, 2008, Federal Register, amendments to Regulation Z under the Home Ownership and Equity Protection Act (HOEPA). The final rule is intended to protect consumers from unfair, deceptive, or abusive acts and practices in mortgage lending and to restrict certain mortgage practices. Higher-Priced Mortgage Loans1 The four key protections of the newly defined category of “higher-priced mortgage loans” for loans secured by a consumer’s principal dwelling will Prohibit a lender from making a loan without regard to the borrower’s ability to repay the loan from income and assets other than the home’s value; Require creditors to verify the income and assets they rely upon to determine repayment ability; Ban any prepayment penalties if the payment can change in the initial four years and, for other higher-priced mortgages, restrict the prepayment penalty period to no more than two years; and Require creditors to establish escrow accounts for property taxes and homeowner’s insurance for first-lien higher-priced mortgage loans. All Loans Secured by a Consumer’s Principal Dwelling In addition, the rules adopt the following protections for all loans secured by a consumer’s principal dwelling though it may not be classified as a higher-priced mortgage: OCC Bulletin 2009-7 Page 2 of 2 Creditors and mortgage brokers are prohibited from coercing a real estate appraiser to misstate a home’s value. -

Legal County Journal Erie

Erie County Legal November 8, 2013 Journal Vol. 96 No. 45 USPS 178-360 96 ERIE - 1 - Erie County Legal Journal Reporting Decisions of the Courts of Erie County The Sixth Judicial District of Pennsylvania Managing Editor: Heidi M. Weismiller PLEASE NOTE: NOTICES MUST BE RECEIVED AT THE ERIE COUNTY BAR ASSOCIATION OFFICE BY 3:00 P.M. THE FRIDAY PRECEDING THE DATE OF PUBLICATION. All legal notices must be submitted in typewritten form and are published exactly as submitted by the advertiser. The Erie County Bar Association will not assume any responsibility to edit, make spelling corrections, eliminate errors in grammar or make any changes in content. The Erie County Legal Journal makes no representation as to the quality of services offered by an advertiser in this publication. Advertisements in the Erie County Legal Journal do not constitute endorsements by the Erie County Bar Association of the parties placing the advertisements or of any product or service being advertised. INDEX NOTICE TO THE PROFESSION ................................................................... 4 COURT OF COMMON PLEAS Certifi cate of Authority Notice ........................................................................ 5 Change of Name Notice .................................................................................. 5 Dissolution Notices .......................................................................................... 5 Incorporation Notices ....................................................................................... 5 Legal Notice -

Unreported Decisions

Unreported Decisions Quick Links Top of page A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W Z Cases are listed alphabetically by first named party. Documents are in PDF format. 2005 Fact Book of Credit-Related Insurance (Apr. 2005) ACORN v. Finance Comm’n of Texas (Tex. Dist. Ct. Apr. 29, 2006) Acree v. General Motors Acceptance (Cal. Super. Ct. Apr. 30, 1996) Advance America, Cash Advance Ctrs. of Florida, Inc. v. The Consolidated City of Jacksonville, Florida (Fla. Cir. Ct. June 1, 2005) Adamson v. ADT Security Services (Cal. Dist. Ct. Apr. 7, 2014) In re Ameriquest Mortgage Co./Mortgage Lending Practices Litigation, MDL No. 1715, Lead Case No. 05-cv-07097 Stipulation for Standstill (N.D. Ill. Feb. 21, 2006) Memorandum Opinion and Order re Temporary Relief (N.D. Ill. May 30, 2006) Stipulation re Form of Notice and Order Thereon (N.D. Ill. June 12, 2006) Complaint for Injunctive Relief (Cal. Super. Ct. Mar. 21, 2006) Permanent Injunction and Final Judgment (Cal. Super. Ct. Mar. 31, 2006) Alabama v. PHH Mortg. Corp. (D.D.C. 2018) (consent judgment) (servicing standards) Alexander Law Firm P.C. Letter (Apr. 2, 2003) American Bankers Insurance Company of Florida (Cal. Dep’t of Ins. May 12, 2015) American Express Centurion Bank v. John LaRose (Conn. Super. Ct. Mar. 3, 2014) Amey v. Southernland Home Improvement Co. (N.D. Ga. Nov. 17, 1997) Ammex v. Jennifer Granholm, Michigan Attorney General (Minn. Dist. Ct. July 18, 2001 ) Anderson v. -

2012 WL 12109913 (NM) (Appellate Brief) Supreme Court of New Mexico

THE BANK OF NEW YORK as Trustees for Popular..., 2012 WL 12109913... 2012 WL 12109913 (N.M.) (Appellate Brief) Supreme Court of New Mexico. THE BANK OF NEW YORK as Trustees for Popular Financial Services Mortgage/Pass Through Certificate Series #2006-D, Plaintiffs-Appellees, v. Joseph A. ROMERO and Mary Romero a/k/a Mary O. Romero a/k/a Maria Romero, Defendants-Appellants. No. 33,224. February 3, 2012. On Writ of Certiorari from the New Mexico Court of Appeals Brief of Amicus Curiae Attorney General of New Mexico Gary K. King, New Mexico Attorney General, Joel Cruz-Esparza, Assistant Attorney General, Karen Meyers, Assistant Attorney General, Consumer Protection Division, Office of New Mexico Attorney General, Gary K. King, 408 Galisteo Street, Santa Fe, NM 87501, (505) 827-6000, (505) 827-5826 (Fax). *i TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTEREST OF AMICUS ........................................................................................................................... 1 2. STATEMENT OF THE CASE ................................................................................................................... 4 3. SUMMARY OF THE ARGUMENT ......................................................................................................... 5 4. STANDARD OF REVIEW ........................................................................................................................ 8 5. ARGUMENTS I. THERE IS GUIDANCE IN NEW MEXICO ON THE PROPER REASONABLE AND NET 8 TANGIBLE STANDARD IN HOME LOAN TRANSACTIONS ................................................................ -

Under Scrutiny, Ameriquest Details Procedures

EBSCOhost http://web.ebscohost.com.proxygw.wrlc.org/ehost/delivery?hid=18&sid=... Record: 1 Title: Under Scrutiny, Ameriquest Details Procedures. (cover story) Authors: Bergquist, Erick Source: American Banker; 6/30/2005, Vol. 170 Issue 125, p1-11, 3p, 3 Color Photographs, 1 Black and White Photograph, 2 Graphs Document Type: Article Subject Terms: *MORTGAGE brokers *FINANCIAL services industry *MORTGAGE loans *STRATEGIC planning *GOVERNMENT regulation Geographic Terms: CALIFORNIA UNITED States Company/Entity: AMERIQUEST Capital Corp. NAICS/Industry Codes: NAICS/Industry Codes 522291 Consumer Lending 522292 Real Estate Credit 522310 Mortgage and Nonmortgage Loan Brokers People: ARNALL, Roland MITAL, Aseem Abstract: Offers a look at Ameriquest Capital Corp., a leading subprime mortgage lender in the U.S., based in California. Report that the company is owned by its only shareholder, Roland Arnall; Importance of advertising in Ameriquest's business strategy; Report that regulators are investigating Ameriquest's retail lending practices; Details of corporate strategy as described by Ameriquest executives; Comments of Aseem Mital, CEO of the umbrella group over Ameriquest's mortgage unit, on regulatory attention given to the company's activities. Full Text Word Count: 3071 ISSN: 0002-7561 Accession Number: 17495771 Database: Business Source Premier Section: Mortgages Under Scrutiny, Ameriquest Details Procedures Despite its ubiquitous brand -- advertised everywhere from major league ballparks to this summer's Rolling Stones tour -- and its phenomenal growth since 2002, little is known about the inner workings of Ameriquest Capital Corp. The nation's top subprime mortgage lender operates out of a 12-story high-rise in southern California, barely distinguishable from the others that dot Orange County's maze of freeways. -

FHFA V JP Morgan Complaint.Pdf

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK FEDERAL HOUSING FINANCE AGENCY, AS CONSERVATOR FOR THE FEDERAL ___ CIV. ___ (___) NATIONAL MORTGAGE ASSOCIATION AND THE FEDERAL HOME LOAN MORTGAGE CORPORATION, COMPLAINT Plaintiff, JURY TRIAL DEMANDED -against- JPMORGAN CHASE & CO.; JPMORGAN CHASE BANK, N.A.; J.P. MORGAN MORTGAGE ACQUISITION CORPORATION; J.P. MORGAN SECURITIES LLC (f/k/a J.P. MORGAN SECURITIES INC.); J.P. MORGAN ACCEPTANCE CORPORATION I; EMC MORTGAGE LLC (f/k/a EMC MORTGAGE CORPORATION); BEAR STEARNS & CO., INC.; STRUCTURED ASSET MORTGAGE INVESTMENTS II INC.; BEAR STEARNS ASSET BACKED SECURITIES I LLC; WAMU ASSET ACCEPTANCE CORPORATION; WAMU CAPITAL CORPORATION; WASHINGTON MUTUAL MORTGAGE SECURITIES CORPORATION; LONG BEACH SECURITIES CORPORATION; CITIGROUP GLOBAL MARKETS, INC.; CREDIT SUISSE SECURITIES (USA) LLC; GOLDMAN, SACHS & CO.; RBS SECURITIES, INC.; DAVID M. DUZYK; LOUIS SCHIOPPO, JR.; CHRISTINE E. COLE; EDWIN F. MCMICHAEL; WILLIAM A. KING; BRIAN BERNARD; MATTHEW E. PERKINS; JOSEPH T. JURKOWSKI, JR.; SAMUEL L. MOLINARO, JR.; THOMAS F. MARANO; KIM LUTTHANS; KATHERINE GARNIEWSKI; JEFFREY MAYER; JEFFREY L. VERSCHLEISER; MICHAEL B. NIERENBERG; RICHARD CAREAGA; DAVID BECK; DIANE NOVAK; THOMAS GREEN; ROLLAND JURGENS; THOMAS G. LEHMANN; STEPHEN FORTUNATO; DONALD WILHELM; MICHAEL J. KULA; CRAIG S. DAVIS; MARC K. MALONE; MICHAEL L. PARKER; MEGAN M. DAVIDSON; DAVID H. ZIELKE; THOMAS W. CASEY; JOHN F. ROBINSON; KEITH JOHNSON; SUZANNE KRAHLING; LARRY BREITBARTH; MARANGAL I. DOMINGO; TROY A. GOTSCHALL; ART DEN HEYER; -

Subprime Lending Lessons from the Ameriquest Settlement Joseph E

Volume 23, Number 5 February 2007 Subprime Lending Lessons from the Ameriquest Settlement Joseph E. Mayk Joseph E. Mayk is of counsel s has been widely reported, early last above the comparable treasury security yield). in the consumer financial year Ameriquest Mortgage Company The oral disclosures, which are in addition to services/retail banking practice and related companies settled a multi- already existing Truth-in-Lending Act (TILA), group of Blank Rome LLP. A state investigation over certain allegedly decep- Real Estate Settlement Procedures Act (RESPA), He is resident in the firm’s Philadelphia office, where his tive consumer lending practices. The settlement and other mandated written disclosures, cover practice focuses on advising included $295 million to repay borrowers with the key loan terms, such as the repayment term, lenders on all aspects of loans originated between January 1, 1999 and interest rate, monthly payment, existence of a pre- consumer finance regulato- December 31, 2005, plus $30 million to pay for payment penalty, whether amounts are escrowed, ry compliance. Mr. Mayk 1 can be reached at mayk@ the investigations. amount and effect of any discount points, and blankrome.com. Like Household Finance Corporation’s nearly adjustable rate disclosures for adjustable rate mort- $500 million settlement with the states in 2002, and gages (ARMs). If the application is not submitted to a lesser extent Citigroup’s $215 million and $70 orally, the substance of the oral disclosures must be million settlements with the Federal Trade Com- provided in writing within three days of receiving mission and the Federal Reserve Board (which the application.