By Avinash Gogineni 2P What Is Brexit? Brexit Is the Term Used for Representing the Process of Britain’S Exit from the EU

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Conservative Party Strategy, 1997-2001: Nation and National Identity

Conservative Party Strategy, 1997-2001: Nation and National Identity A dissertation submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy , Claire Elizabeth Harris Department of Politics, University of Sheffield September 2005 Acknowledgements There are so many people I'd like to thank for helping me through the roller-coaster experience of academic research and thesis submission. Firstly, without funding from the ESRC, this research would not have taken place. I'd like to say thank you to them for placing their faith in my research proposal. I owe a huge debt of gratitude to Andrew Taylor. Without his good humour, sound advice and constant support and encouragement I would not have reached the point of completion. Having a supervisor who is always ready and willing to offer advice or just chat about the progression of the thesis is such a source of support. Thank you too, to Andrew Gamble, whose comments on the final draft proved invaluable. I'd also like to thank Pat Seyd, whose supervision in the first half of the research process ensured I continued to the second half, his advice, experience and support guided me through the challenges of research. I'd like to say thank you to all three of the above who made the change of supervisors as smooth as it could have been. I cannot easily put into words the huge effect Sarah Cooke had on my experience of academic research. From the beginnings of ESRC application to the final frantic submission process, Sarah was always there for me to pester for help and advice. -

Metaphorical Creativity in British Political Discourse on Brexit

JOSIP JURAJ STROSSMAYER UNIVERSITY OF OSIJEK FACULTY OF HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES Lejla Aljukić METAPHORICAL CREATIVITY IN BRITISH POLITICAL DISCOURSE ON BREXIT Doctoral thesis Osijek, 2020 JOSIP JURAJ STROSSMAYER UNIVERSITY OF OSIJEK FACULTY OF HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES Lejla Aljukić METAPHORICAL CREATIVITY IN BRITISH POLITICAL DISCOURSE ON BREXIT Doctoral thesis Supervisor: Sanja Berberović, Ph.D., Associate Professor Osijek, 2020 SVEUČILIŠTE JOSIPA JURJA STROSSMAYERA U OSIJEKU FILOZOFSKI FAKULTET Lejla Aljukić METAFORIČKA KREATIVNOST U BRITANSKOM POLITIČKOM DISKURSU OF BREXITU Doktorska disertacija Mentorica: dr.sc. Sanja Berberović,izv.prof. Osijek, 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS Abbreviations, symbols and font styles ......................................................................... 1 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................. 2 1.1. The aims of dissertation .............................................................................................. 4 2. Theoretical background ............................................................................................. 6 2.1. Historical overview of figurative language studies .................................................... 6 2.2. Cognitive theory of metaphor and metonymy ............................................................ 8 2.2.1. Conceptual metaphor ............................................................................................... 9 2.2.1.1. Conceptual domains -

The Effect of Thatcherism on Nationalist Movements in the United

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara The Bulldog and the Thistle: The Effect of Thatcherism on Nationalist Movements in the United Kingdom A Thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Political Science by Isabella Christina Gabrovsky Committee in charge: Professor Benjamin J. Cohen, Chair Professor Amit Ahuja Professor Bridget L. Coggins Professor Michael Kyle Thompson, Pittsburg State University September 2017 The thesis of Isabella Christina Gabrovsky is approved. ______________________________________________ Amit Ahuja _____________________________________________ Bridget L. Coggins ____________________________________________ Michael Kyle Thompson ____________________________________________ Benjamin J. Cohen, Chair August 2017 The Bulldog and the Thistle: The Effect of Thatcherism on Nationalist Movements in the United Kingdom Copyright © 2017 by Isabella Christina Gabrovsky iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank all the people who have helped me during the writing process. First and foremost, I would like to thank my Committee Chair and Academic Advisor, Professor Benjamin J. Cohen, for his constant support and guidance. I would also like to thank the members of my committee, Professors Amit Ahuja, Bridget Coggins, and Michael Kyle Thompson for their advice and edits. Finally, I would like to acknowledge my family for their unconditional love and support as I completed this thesis. iv ABSTRACT The Bulldog and the Thistle: The Effect of Thatcherism on Nationalist Movements in the United Kingdom by Isabella Christina Gabrovsky The purpose of this thesis is to explain the origins of the new wave of nationalism in the United Kingdom, particularly in Scotland. The popular narrative has been to blame Margaret Thatcher for minority nationalism in the UK as nationalist political parties became more popular during and after her tenure as Prime Minister. -

The Conservatives in Crisis

garnett&l 8/8/03 12:14 PM Page 1 The Conservatives in crisis provides a timely and important analysis incrisis Conservatives The of the Conservative Party’s spell in Opposition following the 1997 general election. It includes chapters by leading academic experts The on the party and commentaries by three senior Conservative politicians: Lord Parkinson, Andrew Lansley MP and Ian Taylor MP. Having been the dominant force in British politics in the twentieth century, the Conservative Party suffered its heaviest general Conservatives election defeats in 1997 and 2001. This book explores the party’s current crisis and assesses the Conservatives’ failure to mount a political recovery under the leadership of William Hague. The Conservatives in crisis includes a detailed examination of the reform of the Conservative Party organisation, changes in ideology in crisis and policy, the party’s electoral fortunes, and Hague’s record as party leader. It also offers an innovative historical perspective on previous Conservative recoveries and a comparison with the revival of the US Republican Party. In the conclusions, the editors assess edited by Mark Garnett and Philip Lynch the failures of the Hague period and examine the party’s performance under Iain Duncan Smith. The Conservatives in crisis will be essential reading for students of contemporary British politics. Mark Garnett is a Visiting Fellow in the Department of Politics at the University of Leicester. Philip Lynch is a Senior Lecturer in Politics at the University of Leicester. Lynch Garnett eds and In memory of Martin Lynch THE CONSERVATIVES IN CRISIS The Tories after 1997 edited by Mark Garnett and Philip Lynch Manchester University Press Manchester and New York distributed exclusively in the USA by Palgrave Copyright © Manchester University Press 2003 While copyright in the volume as a whole is vested in Manchester University Press, copyright in individual chapters belongs to their respective authors. -

HISTORY - Title : - Title : - Title

HISTORY - Title : - Title : - Title : When the six founding members of the European My own party, in a statement endorsed by an overwhelming As far as the functioning and the development of CS1 Britain joining the EEC: La- Economic Community (France, West Germany, majority at our party conference in 1962 said: “The Labour the Community are concerned, the communiqué bour-Tory consensus 1960-1975 Italy, Belgium, the Netherlands and Luxembourg) Party regards the European Community as a great and imagi- […] reported a ‘complete identity of views’ in this signed the Treaty of Rome in 1957 and asked native conception. It believes that the coming together of the regard. In the words of Mr Pompidou, this agree- Britain whether it fancied hanging out to see what six nations which have in the past so often been torn by war ment concerns the idea of ‘a Europe composed of Why was it so difficult for the UK to might happen, Britain said thanks, but no thanks. and economic rivalry is, in the context of Western Europe, a nations concerned with maintaining their identity join the EEC? […] step of great significance.” but having decided to work together to attain true By the early 1960s, though, Harold Macmillan, the Ten weeks ago […] I said to the House of Commons: “I unity.’ […] The French also welcomed the ac- Structure prime minister, had realised the mistake (it’s the want the House, the country and our friends abroad to know ceptance by the British of the ‘Community prefer- Applying to join the EEC 1961- trade, stupid) and started making overtures to- that the Government are approaching the discussions I have ence’ in agriculture […]. -

Paul Stephenson

Paul Stephenson Director of Communications, Vote Leave September 2015 – June 2016 21 August 2020 The lead-up to the campaign, September 2015 – March 2016 UK in a Changing Europe (UKICE): How difficult, if at all, was it to persuade you to join Vote Leave? Paul Stephenson (PS): Persuading my wife was the most difficult thing I think. I was working in the British Bankers’ Association. I had a comfortable job, comfortable existence. It was interesting work but I had done it for a number of years and was interested in a new challenge. I had known Dom(inic Cummings) for quite a while, not well but we mixed in similar political circles. It’s basically the Eurosceptic clan that was founded by Rodney Leach back in the day, probably the Godfather of the whole movement. It was a great shame that he died mid-way through the campaign. It sounded exciting and I just love political campaigns. Actually, the thing for me was that I wasn’t a Leaver until the renegotiation. I think that speaks to the failure of the renegotiation in some ways. I helped set up Open Europe back in the day. I did believe in EU reform. I was a Eurosceptic. I just wasn’t a UKIP-er. And, actually, if you go back all that time, the ‘No’ Euro campaign was ‘Europe, yes, Euro, no’. The reason Cameron was doing the renegotiation was he wanted to win that swing middle over who didn’t particularly love the EU but would stay in if it changed. -

Government by Referendum

Government by referendum QVORTRUP 9781526130037 PRINT.indd 1 25/01/2018 15:15 ii POCKETPOCKET POLITICSPOLITICS SERIES EDITOR: BILL JONES SERIES EDITOR: BILL JONES Pocket politics presents short, pithy summaries of complex topicsPocket on politics socio- presents political issuesshort, pithyboth insummaries Britain and of overseas.complex Academicallytopics on socio-political sound, accessible issues bothand aimedin Britain at the and interested overseas. Academicallygeneral reader, sound, the accessibleseries will andaddress aimed a subject at the interested range includinggeneral political reader, ideas, the series economics, will address society, a subjectthe machinery range of includinggovernment political and international ideas, economics, issues. society, Unusually, the machineryperhaps, ofauthors government are encouraged, and international should issues.they choose, Unusually, to offer perhaps, their authorsown areconclusions encouraged, rather should than they strive choose, for mere to offeracademic their own conclusionsobjectivity. Therather series than will strive provide for mere stimulating academic intellectual objectivity. accessThe series to the will problems provide of stimulating the modern intellectual world in aaccess user- friendly to the problems of the modernformat. world in a user-friendly format. Previously published The TrumpPreviously revolt publishedEdward Ashbee ReformThe of Trumpthe House revolt of LordsEdward Philip Ashbee Norton Lobbying: An appraisal Wyn Grant Power in modern Russia: Strategy and mobilisation Andrew Monaghan Reform of the House of Lords Philip Norton QVORTRUP 9781526130037 PRINT.indd 2 25/01/2018 15:15 Government by referendum Matt Qvortrup Manchester University Press QVORTRUP 9781526130037 PRINT.indd 3 25/01/2018 15:15 Copyright © Matt Qvortrup 2018 The right of Matt Qvortrup to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. -

Brexit the Future of Two Unions

Brexit The Future of Two Unions Daniel Kenealy, John Peterson, and Richard Corbett 1 00-Kenealy-FM.indd 1 22/06/17 10:34 AM 1 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OX2 6DP, United Kingdom Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries © Oxford University Press 2017 The moral rights of the authors have been asserted All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer Printed in Great Britain by Ashford Colour Press Ltd, Gosport, Hampshire Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. Oxford disclaims any responsibility for the materials contained in any third party website referenced in this work. 00-Kenealy-FM.indd 2 22/06/17 10:34 AM Summary In June 2016, the United Kingdom (UK) held a referendum on continuing its European Union (EU) membership. -

Richard Tice

Richard Tice Chairman of the Brexit Party November 2018 – January 2021 MEP for East of England July 2019 – January 2020 Founder of Leave Means Leave July 2016 – January 2020 Co-founder of Leave.EU July 2015 – June 2016 11 September 2020 Euroscepticism UK in a Changing Europe (UKICE): What first made you a Eurosceptic? Richard Tice (RT): When the big debate was happening really in the 1990s about whether or not the UK should join the euro, I looked at it. I am a business- person, but my degree was quantity surveying, construction economics, and did economics at A Level. It just struck me, that I thought the whole project was completely flawed in that if you take away the right to set your own interest rate according to your own economy’s needs, then essentially it is like taking away a leg of a chair. You are making the chair substantially less stable and you are reducing your own flexibility. So I was very anxious about that. I wrote a three-page letter to Gordon Brown and I knew Nick Herbert, who you know was an MP. He was an old mate, and he was with Rodney Leach. He was the first director of Business for Sterling. So I got involved, gave them some money, ended up becoming a director of it, and it went from there. UKICE: Lots of people objected to the Euro but didn’t want to see the UK leave the EU. At that stage, would you have put yourself in that camp? Page 1/22 RT: I was very sceptical of the EU at that time, but in a sense, I was more focused on trying to make sure we didn’t join the Euro. -

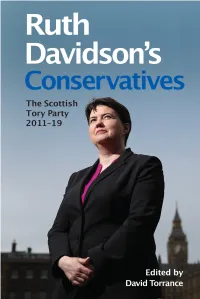

Ruth Davidson's Conservatives

Ruth Davidson’s Conservatives 66343_Torrance.indd343_Torrance.indd i 118/05/208/05/20 33:06:06 PPMM 66343_Torrance.indd343_Torrance.indd iiii 118/05/208/05/20 33:06:06 PPMM Ruth Davidson’s Conservatives The Scottish Tory Party, 2011–19 Edited by DAVID TORRANCE 66343_Torrance.indd343_Torrance.indd iiiiii 118/05/208/05/20 33:06:06 PPMM Edinburgh University Press is one of the leading university presses in the UK. We publish academic books and journals in our selected subject areas across the humanities and social sciences, combining cutting-edge scholarship with high editorial and production values to produce academic works of lasting importance. For more information visit our website: edinburghuniversitypress.com © editorial matter and organisation David Torrance, 2020 © the chapters their several authors, 2020 Edinburgh University Press Ltd The Tun – Holyrood Road, 12(2f) Jackson’s Entry, Edinburgh EH8 8PJ Typeset in 10/13 Giovanni by IDSUK (DataConnection) Ltd, and printed and bound in Great Britain. A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 1 4744 5562 6 (hardback) ISBN 978 1 4744 5563 3 (paperback) ISBN 978 1 4744 5564 0 (webready PDF) ISBN 978 1 4744 5565 7 (epub) The right of David Torrance to be identifi ed as the editor of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, and the Copyright and Related Rights Regulations 2003 (SI No. 2498). 66343_Torrance.indd343_Torrance.indd iivv 118/05/208/05/20 33:06:06 PPMM CONTENTS List of Tables / vii Notes on the Contributors -

Ambrosetti E La Consulenza Strategica in Cina

Corso di Laurea Magistrale in Lingue e Istituzioni economiche e giuridiche dell’Asia e dell’Africa Mediterranea Tesi di Laurea The European House - Ambrosetti e la consulenza strategica in Cina. Relazione su un’esperienza di stage tra i grandi del management consulting Relatore Prof. Renzo Riccardo Cavalieri Correlatore Dott.ssa Sara D’Attoma Laureando Anita Tormena Matricola 964747 Anno Accademico 2015 / 2016 Ringraziamenti Arrivata alla fine di questo lungo, difficile ma bellissimo percorso vorrei ringraziare tutte le persone che mi hanno sostenuto e accompagnato. Il primo ringraziamento va al mio Relatore, il professor Renzo Cavalieri, per la disponibilità e l’aiuto e a tutto lo staff di The European House - Ambrosetti di Shanghai: Ilaria, Lili, Lucia e in particolare Mattia Marino e Paolo Borzatta per gli insegnamenti impartiti. Un ringraziamento importante va poi a tutti quelli che hanno sempre creduto in me e mi hanno dato la forza per raggiungere questo traguardo. In particolare ai miei genitori, perché nonostante la distanza sono sempre al mio fianco. A mio fratello, ai nonni e a tutta la famiglia, punto fermo da cui partire e rifugio sicuro dove tornare. Ad Alexa, perché semplicemente non serve mai dire niente. A Marta, perché le scelte sbagliate sono sempre quelle vincenti. Agli amici di una vita: Silvia, Patrizio, Franco e Alessandra. A Gabriele, per la sua presenza discreta ma importante. A mia zia Isa, per le confidenze e i momenti insieme. Infine, l’ultimo ma più speciale ringraziamento va a Beppe, per tutto quello che fa e soprattutto -

US Ruling Class Prepares Attack on Social Security

US Ruling Class Prepares Attack on Social Security By Tom Eley Region: USA Global Research, September 09, 2010 Theme: Global Economy World Socialist Web Site 8 September 2010 Prominent figures in the US ruling elite have recently made a series of statements that forewarn of massive cuts in social spending, up to and including Social Security, the bedrock federal insurance entitlement for elderly and disabled workers. These comments reveal that, whatever the precise outcome of the midterm elections on November 7, they will set the stage for a bipartisan assault, in the name of “fiscal responsibility,” on what remains of the social reforms of the last century. The knives are already being sharpened for a long-awaited attack on Social Security. In a rude and provocative e-mail to the president of the Older Women’s League dated August 23, former Republican Senator Alan Simpson—appointed by President Obama as co-chair of the National Commission on Fiscal Responsibility and Reform—revealed his deep hatred of both Social Security and the working people who depend upon it. Social Security “has reached a point now where it’s like a milk cow with 310 million tits! [sic],” Simpson said. He blasted its recipients—retirees, those maimed and sickened by their work, and dependent survivors of dead workers—who, he said “milk it to the last degree.” In an earlier outburst—in June, Simpson was caught on tape berating an independent journalist— he revealed the ruthless logic behind the ruling class drive for cuts: Workers, whom Simpson dubbed “the lesser people,” live too long.