NUCLEAR FISSION- a Tunneling Process the ATOMIC NUCLEUS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Richard G. Hewlett and Jack M. Holl. Atoms

ATOMS PEACE WAR Eisenhower and the Atomic Energy Commission Richard G. Hewlett and lack M. Roll With a Foreword by Richard S. Kirkendall and an Essay on Sources by Roger M. Anders University of California Press Berkeley Los Angeles London Published 1989 by the University of California Press Berkeley and Los Angeles, California University of California Press, Ltd. London, England Prepared by the Atomic Energy Commission; work made for hire. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Hewlett, Richard G. Atoms for peace and war, 1953-1961. (California studies in the history of science) Bibliography: p. Includes index. 1. Nuclear energy—United States—History. 2. U.S. Atomic Energy Commission—History. 3. Eisenhower, Dwight D. (Dwight David), 1890-1969. 4. United States—Politics and government-1953-1961. I. Holl, Jack M. II. Title. III. Series. QC792. 7. H48 1989 333.79'24'0973 88-29578 ISBN 0-520-06018-0 (alk. paper) Printed in the United States of America 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 CONTENTS List of Illustrations vii List of Figures and Tables ix Foreword by Richard S. Kirkendall xi Preface xix Acknowledgements xxvii 1. A Secret Mission 1 2. The Eisenhower Imprint 17 3. The President and the Bomb 34 4. The Oppenheimer Case 73 5. The Political Arena 113 6. Nuclear Weapons: A New Reality 144 7. Nuclear Power for the Marketplace 183 8. Atoms for Peace: Building American Policy 209 9. Pursuit of the Peaceful Atom 238 10. The Seeds of Anxiety 271 11. Safeguards, EURATOM, and the International Agency 305 12. -

Grappling with the Bomb: Britain's Pacific H-Bomb Tests

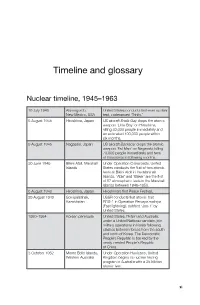

Timeline and glossary Nuclear timeline, 1945–1963 16 July 1945 Alamogordo, United States conducts first-ever nuclear New Mexico, USA test, codenamed ‘Trinity .’ 6 August 1945 Hiroshima, Japan US aircraft Enola Gay drops the atomic weapon ‘Little Boy’ on Hiroshima, killing 80,000 people immediately and an estimated 100,000 people within six months . 9 August 1945 Nagasaki, Japan US aircraft Bockscar drops the atomic weapon ‘Fat Man’ on Nagasaki, killing 70,000 people immediately and tens of thousands in following months . 30 June 1946 Bikini Atoll, Marshall Under Operation Crossroads, United Islands States conducts the first of two atomic tests at Bikini Atoll in the Marshall Islands. ‘Able’ and ‘Baker’ are the first of 67 atmospheric tests in the Marshall Islands between 1946–1958 . 6 August 1948 Hiroshima, Japan Hiroshima’s first Peace Festival. 29 August 1949 Semipalatinsk, USSR conducts first atomic test Kazakhstan RDS-1 in Operation Pervaya molniya (Fast lightning), dubbed ‘Joe-1’ by United States . 1950–1954 Korean peninsula United States, Britain and Australia, under a United Nations mandate, join military operations in Korea following clashes between forces from the south and north of Korea. The Democratic People’s Republic is backed by the newly created People’s Republic of China . 3 October 1952 Monte Bello Islands, Under Operation Hurricane, United Western Australia Kingdom begins its nuclear testing program in Australia with a 25 kiloton atomic test . xi GRAPPLING WITH THE BOMB 1 November 1952 Bikini Atoll, Marshall United States conducts its first Islands hydrogen bomb test, codenamed ‘Mike’ (10 .4 megatons) as part of Operation Ivy . -

Models of the Atomic Nucleus

Models of the Atomic Nucleus Second Edition Norman D. Cook Models of the Atomic Nucleus Unification Through a Lattice of Nucleons Second Edition 123 Prof. Norman D. Cook Kansai University Dept. Informatics 569 Takatsuki, Osaka Japan [email protected] Additional material to this book can be downloaded from http://extras.springer.com. ISBN 978-3-642-14736-4 e-ISBN 978-3-642-14737-1 DOI 10.1007/978-3-642-14737-1 Springer Heidelberg Dordrecht London New York Library of Congress Control Number: 2010936431 © Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2006, 2010 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilm or in any other way, and storage in data banks. Duplication of this publication or parts thereof is permitted only under the provisions of the German Copyright Law of September 9, 1965, in its current version, and permission for use must always be obtained from Springer. Violations are liable to prosecution under the German Copyright Law. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. Cover design: WMXDesign GmbH, Heidelberg Printed on acid-free paper Springer is part of Springer Science+Business Media (www.springer.com) Preface to the Second Edition Already by the 1970s, some theorists had declared that nuclear structure physics was a “closed chapter” in science, but since then it has repeatedly been found necessary to re-open this closed chapter to address old problems and to explain new phenom- ena. -

Appendix: Key Concepts and Vocabulary for Nuclear Energy

Appendix: Key Concepts and Vocabulary for Nuclear Energy The likelihood of fission depends on, among other Power Plant things, the energy of the incoming neutron. Some In most power plants around the world, heat, usually nuclei can undergo fission even when hit by a low- produced in the form of steam, is converted to energy neutron. Such elements are called fissile. electricity. The heat could come through the burning The most important fissile nuclides are the uranium of coal or natural gas, in the case of fossil-fueled isotopes, uranium-235 and uranium-233, and the power plants, or the fission of uranium or plutonium plutonium isotope, plutonium-239. Isotopes are nuclei. The rate of electrical power production in variants of the same chemical element that have these power plants is usually measured in megawatts the same number of protons and electrons, but or millions of watts, and a typical large coal or nuclear differ in the number of neutrons. Of these, only power plant today produces electricity at a rate of uranium-235 is found in nature, and it is found about 1,000 megawatts. A much smaller physical only in very low concentrations. Uranium in nature unit, the kilowatt, is a thousand watts, and large contains 0.7 percent uranium-235 and 99.3 percent household appliances use electricity at a rate of a few uranium-238. This more abundant variety is an kilowatts when they are running. The reader will have important example of a nucleus that can be split only heard about the “kilowatt-hour,” which is the amount by a high-energy neutron. -

The Los Alamos Thermonuclear Weapon Project, 1942-1952

Igniting The Light Elements: The Los Alamos Thermonuclear Weapon Project, 1942-1952 by Anne Fitzpatrick Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY STUDIES Approved: Joseph C. Pitt, Chair Richard M. Burian Burton I. Kaufman Albert E. Moyer Richard Hirsh June 23, 1998 Blacksburg, Virginia Keywords: Nuclear Weapons, Computing, Physics, Los Alamos National Laboratory Igniting the Light Elements: The Los Alamos Thermonuclear Weapon Project, 1942-1952 by Anne Fitzpatrick Committee Chairman: Joseph C. Pitt Science and Technology Studies (ABSTRACT) The American system of nuclear weapons research and development was conceived and developed not as a result of technological determinism, but by a number of individual architects who promoted the growth of this large technologically-based complex. While some of the technological artifacts of this system, such as the fission weapons used in World War II, have been the subject of many historical studies, their technical successors -- fusion (or hydrogen) devices -- are representative of the largely unstudied highly secret realms of nuclear weapons science and engineering. In the postwar period a small number of Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory’s staff and affiliates were responsible for theoretical work on fusion weapons, yet the program was subject to both the provisions and constraints of the U. S. Atomic Energy Commission, of which Los Alamos was a part. The Commission leadership’s struggle to establish a mission for its network of laboratories, least of all to keep them operating, affected Los Alamos’s leaders’ decisions as to the course of weapons design and development projects. -

Atomic Engery Education Volume Four.Pdf

~ t a t e of ~ ofua 1952 SCIENTIFIC AND SOCIAL ASPECTS OF ATOMIC ENERGY (A Source Book /or General Use in Colleges) Volume IV The Iowa Plan for Atomic Energy Education Issu ed by the D epartment of Public Instruction J essie M. Parker Superintendent Des Moines, Iowa Published by the State .of Iowa ''The release of atomic energy on a large scale is practical. It is reasonable to anticipate that this new source of energy will cause profound changes in our present way of life." - Quoted from the Copyright 1952 Atomic Energy Act of 1946. by The State of Iowa "Unless the people have the essential facts about atonuc energy, they cannot act wisely nor can they act democratically."-. -David I Lilienthal, formerly chairman of the Atomic Energy Com.mission. IOWA PLAN FOR ATOMIC ENERGY EDUCATION FOREWORD Central Planning Committee About five years ago the Iowa State Department of Public Instruction became impressed with the need for promoting Atomic Energy Education throughout the state. Following a series of Glenn Hohnes, Iowa State Col1ege, Ames, General Chairman conferences, in which responsible educators and laymen shared their views on this problem, Emil C. Miller, Luther College, Decorah plans were made to develop material for use at the elementary, high school, college, and Barton Morgan, Iowa State College, Ames adult education levels. This volume is a resource hook for use with and by college students. M. J. Nelson, Iowa State Teachers College, Cedar Falls Actually, many of the materials in this volume have their origin in the Atomic Energy Day Hew Roberts, State University of Iowa, Iowa City programs which were sponsored by Cornell College and Luther College two or three years L. -

Module01 Nuclear Physics and Reactor Theory

Module I Nuclear physics and reactor theory International Atomic Energy Agency, May 2015 v1.0 Background In 1991, the General Conference (GC) in its resolution RES/552 requested the Director General to prepare 'a comprehensive proposal for education and training in both radiation protection and in nuclear safety' for consideration by the following GC in 1992. In 1992, the proposal was made by the Secretariat and after considering this proposal the General Conference requested the Director General to prepare a report on a possible programme of activities on education and training in radiological protection and nuclear safety in its resolution RES1584. In response to this request and as a first step, the Secretariat prepared a Standard Syllabus for the Post- graduate Educational Course in Radiation Protection. Subsequently, planning of specialised training courses and workshops in different areas of Standard Syllabus were also made. A similar approach was taken to develop basic professional training in nuclear safety. In January 1997, Programme Performance Assessment System (PPAS) recommended the preparation of a standard syllabus for nuclear safety based on Agency Safely Standard Series Documents and any other internationally accepted practices. A draft Standard Syllabus for Basic Professional Training Course in Nuclear Safety (BPTC) was prepared by a group of consultants in November 1997 and the syllabus was finalised in July 1998 in the second consultants meeting. The Basic Professional Training Course on Nuclear Safety was offered for the first time at the end of 1999, in English, in Saclay, France, in cooperation with Institut National des Sciences et Techniques Nucleaires/Commissariat a l'Energie Atomique (INSTN/CEA). -

Chapter 8. the Atomic Nucleus

Chapter 8. The Atomic Nucleus Notes: • Most of the material in this chapter is taken from Thornton and Rex, Chapters 12 and 13. 8.1 Nuclear Properties Atomic nuclei are composed of protons and neutrons, which are referred to as nucleons. Although both types of particles are not fundamental or elementary, they can still be considered as basic constituents for the purpose of understanding the atomic nucleus. Protons and neutrons have many characteristics in common. For example, their masses are very similar with 1.0072765 u (938.272 MeV) for the proton and 1.0086649 u (939.566 MeV) for the neutron. The symbol ‘u’ stands for the atomic mass unit defined has one twelfth of the mass of the main isotope of carbon (i.e., 12 C ), which is known to contain six protons and six neutrons in its nucleus. We thus have that 1 u = 1.66054 ×10−27 kg (8.1) = 931.49 MeV/c2 . Protons and neutrons also both have the same intrinsic spin, but different magnetic moments (see below). Their main difference, however, pertains to their electrical charges: the proton, as we know, has a charge of +e , while the neutron has none, as its name implies. Atomic nuclei are designated using the symbol A Z XN , (8.2) with Z, N and A the number of protons (atomic element number), the number of neutrons, and the atomic mass number ( A = Z + N ), respectively, while X is the chemical element symbol. It is often the case that Z and N are omitted, when there is no chance of confusion. -

Chapter 2 the Atomic Nucleus

Nuclear Science—A Guide to the Nuclear Science Wall Chart ©2018 Contemporary Physics Education Project (CPEP) Chapter 2 The Atomic Nucleus Searching for the ultimate building blocks of the physical world has always been a central theme in the history of scientific research. Many acclaimed ancient philosophers from very different cultures have pondered the consequences of subdividing regular, tangible objects into their smaller and smaller, invisible constituents. Many of them believed that eventually there would exist a final, inseparable fundamental entity of matter, as emphasized by the use of the ancient Greek word, atoos (atom), which means “not divisible.” Were these atoms really the long sought-after, indivisible, structureless building blocks of the physical world? The Atom By the early 20th century, there was rather compelling evidence that matter could be described by an atomic theory. That is, matter is composed of relatively few building blocks that we refer to as atoms. This theory provided a consistent and unified picture for all known chemical processes at that time. However, some mysteries could not be explained by this atomic theory. In 1896, A.H. Becquerel discovered penetrating radiation. In 1897, J.J. Thomson showed that electrons have negative electric charge and come from ordinary matter. For matter to be electrically neutral, there must also be positive charges lurking somewhere. Where are and what carries these positive charges? A monumental breakthrough came in 1911 when Ernest Rutherford and his coworkers conducted an experiment intended to determine the angles through which a beam of alpha particles (helium nuclei) would scatter after passing through a thin foil of gold. -

Microscopic Theory of Nuclear Fission: a Review

Reports on Progress in Physics REVIEW Microscopic theory of nuclear fission: a review To cite this article: N Schunck and L M Robledo 2016 Rep. Prog. Phys. 79 116301 Manuscript version: Accepted Manuscript Accepted Manuscript is “the version of the article accepted for publication including all changes made as a result of the peer review process, and which may also include the addition to the article by IOP Publishing of a header, an article ID, a cover sheet and/or an ‘Accepted Manuscript’ watermark, but excluding any other editing, typesetting or other changes made by IOP Publishing and/or its licensors” This Accepted Manuscript is © © 2016 IOP Publishing Ltd. During the embargo period (the 12 month period from the publication of the Version of Record of this article), the Accepted Manuscript is fully protected by copyright and cannot be reused or reposted elsewhere. As the Version of Record of this article is going to be / has been published on a subscription basis, this Accepted Manuscript is available for reuse under a CC BY-NC-ND 3.0 licence after the 12 month embargo period. After the embargo period, everyone is permitted to use copy and redistribute this article for non-commercial purposes only, provided that they adhere to all the terms of the licence https://creativecommons.org/licences/by-nc-nd/3.0 Although reasonable endeavours have been taken to obtain all necessary permissions from third parties to include their copyrighted content within this article, their full citation and copyright line may not be present in this Accepted Manuscript version. -

Nuclear Physics Sections 10.1-10.7

James T. Shipman Jerry D. Wilson Charles A. Higgins, Jr. Chapter 10 Nuclear Physics Nuclear Physics • The characteristics of the atomic nucleus are important to our modern society. • Diagnosis and treatment of cancer and other diseases • Geological and archeological dating • Chemical analysis • Nuclear energy and nuclear diposal • Formation of new elements • Radiation of solar energy • Generation of electricity Audio Link Intro Early Thoughts about Elements • The Greek philosophers (600 – 200 B.C.) were the first people to speculate about the basic substances of matter. • Aristotle speculated that all matter on earth is composed of only four elements: earth, air, fire, and water. • He was wrong on all counts! Section 10.1 Names and Symbols of Common Elements Section 10.1 The Atom • All matter is composed of atoms. • An atom is composed of three subatomic particles: electrons (-), protons (+), and neutrons (0) • The nucleus of the atom contains the protons and the neutrons (also called nucleons.) • The electrons surround (orbit) the nucleus. • Electrons and protons have equal but opposite charges. Section 10.2 Major Constituents of an Atom Section 10.2 The Atomic Nucleus • Protons and neutrons have nearly the same mass and are 2000 times more massive than an electron. • Discovery – Electron (J.J. Thomson in 1897), Proton (Ernest Rutherford in 1918), and Neutron (James Chadwick in 1932) Section 10.2 Rutherford’s Alpha- Scattering Experiment • J.J. Thomson’s “plum pudding” model predicted the alpha particles would pass through the evenly distributed positive charges in the gold atoms. α particle = helium nucleus Section 10.2 Rutherford’s Alpha- Scattering Experiment • Only 1 out of 20,000 alpha particles bounced back. -

The Manhattan Project: Making the Atomic Bomb” Is a Short History of the Origins and Develop- Ment of the American Atomic Bomb Program During World War H

f.IOE/MA-0001 -08 ‘9g [ . J vb JMkirlJkhilgUimBA’mmml — .— Q RDlmm UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY ,:.. .- ..-. .. -,.,,:. ,.<,.;<. ~-.~,.,.- -<.:,.:-,------—,.--,,p:---—;-.:-- ---:---—---- -..>------------.,._,.... ,/ ._ . ... ,. “ .. .;l, ..,:, ..... ..’, .’< . Copies of this publication are available while supply lasts from the OffIce of Scientific and Technical Information P.O. BOX 62 Oak Ridge, TN 37831 Attention: Information Services Telephone: (423) 576-8401 Also Available: The United States Department of Energy: A Summary History, 1977-1994 @ Printed with soy ink on recycled paper DO13MA-0001 a +~?y I I Tho PROJEOT UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY F.G. Gosling History Division Executive Secretariat Management and Administration Department of Energy ]January 1999 edition . DISCLAIMER This report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States Government. Neither the United States Government nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, make any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States Government or any agency thereof. The views and opinions of authors expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States Government or any agency thereof. I DISCLAIMER Portions of this document may be illegible in electronic image products. Images are produced from the best available original document. 1 Foreword The Department of Energy Organization Act of 1977 brought together for the first time in one department most of the Federal Government’s energy programs.