The Relationship Between Music and Games Mark Havryliv University of Wollongong

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Games for Windows Windows 7 Download Driver Truck Driver Game Exe for Windows 7

games for windows windows 7 download driver Truck driver game exe for windows 7. Most people looking for Truck driver game exe for windows 7 downloaded: Euro Truck Simulator 2. Euro Truck Simulator 2 is a game in which you can travel across Europe as king of the road, a trucker who delivers important cargo across impressive distances. SCANIA Truck Driving Simulator. Scania Truck Driving Simulator is a game in which you can get behind the wheel of one of the most iconic trucks on the road. Euro Truck Simulator. Euro Truck Simulator is a truck simulation game set in Europe. UK Truck Simulator. Hit the road in UK Truck Simulator! Start the ignition and set off for the motorway. 18 Wheels of Steel Pedal to the Metal. Take your show on the road. Drive your rig to make it big and build your business. Similar choice. › Download euro truck driver .exe › Truck driver setup exe › Euro truck driver exe download › Free game for laptop truck drivers › Scania truck driver exe › Uk truck driver pc game download. Programs for query ″truck driver game exe for windows 7″ Gang beasts. Gang Beasts is a silly local multiplayer party game with doughy ragdoll physics and horrific environmental hazards. multiplayer party game with doughy . trucks , and suspended platforms. The game . German Truck Simulator. Start the engine and set off for German autobahns in German Truck Simulator! . in German Truck Simulator! Drive across . 7 major European truck manufacturers, including . Farm Frenzy. Slip into a pair of overalls and try your hand at running a farm! . -

´Electronique Based On

Vincenzo Lombardo,∗ Andrea Valle,∗ John Fitch,† Kees Tazelaar,∗∗ A Virtual-Reality Stefan Weinzierl,†† and Reconstruction of Poeme` Wojciech Borczyk§ ´ ∗Centro Interdipartimentale di Ricerca Electronique Based on sulla Multimedialita` e l’Audiovisivo Universita` di Torino Philological Research Virtual Reality and Multi Media Park ViaS.Ottavio20 10123 Torino, Italy [email protected]; [email protected] †Department of Computer Science University of Bath BA2 7AY, Bath, United Kingdom [email protected] ∗∗Institute of Sonology Royal Conservatory Juliana v. Stolberglaan 1 2595CA Den Haag, The Netherlands [email protected] ††Fachgebiet Audiokommunikation Technische Universitat¨ Berlin Einsteinufer 17c D-10587 Berlin, Germany [email protected] §Instytut Informatyki Wydzial Automatyki Elektroniki i Informatyki Politechniki Slaskiej´ Akademicka 16 44-100 Gliwice, Poland [email protected] “The last word is imagination” [Le dernier mot est Electronique´ (1958). This seminal work was Varese’s` imagination] (Edgard Varese,` in Charbonnier 1970, only purely electroacoustic work (apart from the p. 79): with this statement, Varese` replies to George very short La Procession de Verges` of 1955; Bernard Charbonnier, closing a 1955 interview about the 1987, p. 238), and also, to the best of our knowledge, aesthetic postulates of his long but difficult career. the first electroacoustic work in the history of While speaking about the relationship between music to be structurally integrated in an audiovisual music and image, Varese` declares—somewhat context (cf. Chadabe 1997). surprisingly—that he would like to see a film based The history of Poeme` Electronique´ , as docu- on his last completed orchestral work, Deserts´ mented by Petit (1958) and Treib (1996), goes back (1954). -

Akrata, for 16 Winds by Iannis Xenakis: Analyses1

AKRATA, FOR 16 WINDS BY IANNIS XENAKIS: ANALYSES1 Stéphan Schaub: Ircam / University of Paris IV Sorbonne In Makis Solomos, Anastasia Georgaki, Giorgos Zervos (ed.), Definitive Proceedings of the “International Symposium Iannis Xenakis” (Athens, May 2005), www.iannis-xenakis.org, October 2006. Paper first published in A. Georgaki, M. Solomos (éd.), International Symposium Iannis Xenakis. Conference Proceedings, Athens, May 2005, p. 138-149. This paper was selected for the Definitive Proceedings by the scientific committee of the symposium: Anne-Sylvie Barthel-Calvet (France), Agostino Di Scipio (Italy), Anastasia Georgaki (Greece), Benoît Gibson (Portugal), James Harley (Canada), Peter Hoffmann (Germany), Mihu Iliescu (France), Sharon Kanach (France), Makis Solomos (France), Ronald Squibbs (USA), Georgos Zervos (Greece) … a sketch in which I make use of the theory of groups 2 ABSTRACT In the following paper the author presents a reconstruction of the formal system developed by Iannis Xenakis for the composition of Akrata, for 16 winds (1964-1965). The reconstruction is based on a study of both the score and the composer’s preparatory sketches to his composition. Akrata chronologically follows Herma for piano (1961) and precedes Nomos Alpha for cello (1965-1966). All three works fall within the “symbolic music” category. As such, they were composed under the constraint of having a temporal function unfold “algorithmically” the work’s “outside time” architecture into the “in time” domain. The system underlying Akrata, undergoes several mutations over the course of the music’s unfolding. In its last manifestation, it bears strong resemblances with the better known system later applied to the composition of Nomos Alpha. -

Expanding Horizons: the International Avant-Garde, 1962-75

452 ROBYNN STILWELL Joplin, Janis. 'Me and Bobby McGee' (Columbia, 1971) i_ /Mercedes Benz' (Columbia, 1971) 17- Llttle Richard. 'Lucille' (Specialty, 1957) 'Tutti Frutti' (Specialty, 1955) Lynn, Loretta. 'The Pili' (MCA, 1975) Expanding horizons: the International 'You Ain't Woman Enough to Take My Man' (MCA, 1966) avant-garde, 1962-75 'Your Squaw Is On the Warpath' (Decca, 1969) The Marvelettes. 'Picase Mr. Postman' (Motown, 1961) RICHARD TOOP Matchbox Twenty. 'Damn' (Atlantic, 1996) Nelson, Ricky. 'Helio, Mary Lou' (Imperial, 1958) 'Traveling Man' (Imperial, 1959) Phair, Liz. 'Happy'(live, 1996) Darmstadt after Steinecke Pickett, Wilson. 'In the Midnight Hour' (Atlantic, 1965) Presley, Elvis. 'Hound Dog' (RCA, 1956) When Wolfgang Steinecke - the originator of the Darmstadt Ferienkurse - The Ravens. 'Rock All Night Long' (Mercury, 1948) died at the end of 1961, much of the increasingly fragüe spirit of collegial- Redding, Otis. 'Dock of the Bay' (Stax, 1968) ity within the Cologne/Darmstadt-centred avant-garde died with him. Boulez 'Mr. Pitiful' (Stax, 1964) and Stockhausen in particular were already fiercely competitive, and when in 'Respect'(Stax, 1965) 1960 Steinecke had assigned direction of the Darmstadt composition course Simón and Garfunkel. 'A Simple Desultory Philippic' (Columbia, 1967) to Boulez, Stockhausen had pointedly stayed away.1 Cage's work and sig- Sinatra, Frank. In the Wee SmallHoun (Capítol, 1954) Songsfor Swinging Lovers (Capítol, 1955) nificance was a constant source of acrimonious debate, and Nono's bitter Surfaris. 'Wipe Out' (Decca, 1963) opposition to himz was one reason for the Italian composer being marginal- The Temptations. 'Papa Was a Rolling Stone' (Motown, 1972) ized by the Cologne inner circle as a structuralist reactionary. -

Transgressing the Wall. Mauricio Kagel and Decanonization of the Musical Performance

Bulletin of the Transilvania University of Braşov Series VIII: Performing Arts • Vol. 13 (60) No. 2 - 2020 https://doi.org/10.31926/but.pa.2020.13.62.2.2 Transgressing the Wall. Mauricio Kagel and Decanonization of the musical performance Laurențiu BELDEAN1, Malgorzata LISECKA2 Abstract: The article discusses selected some musical concept by Maurcio Kagel (1931–2008), one of the most significant Argentinian composer. The analysis concerns two issues related to Kagel’s work. First of all, the composer’s approach to musical theatre as an artistic tool for demolishing a wall put in cultural tradition between a performer and a musical work – just like Berlin Wall which turned the politics paradigm in order to melt two political positions into one. Kagel’s negation of the structure’s coherence in traditional musical canon became the basis of his conceptualization which implies a collapse within the wall between the musical instrument and the performer. Aforementioned performer doesn’t remain in the passive role, but is engaged in the art with his whole body as authentic, vivid instrument. Secondly, this article concerns the actual threads of Kagel’s music, as he was interested in enclosing in his work contemporary social and political issues. As the context of the analyze the authors used the ideas of Paulo Freire (with his concept of the pedagogy of freedom) and Augusto Boal (with his concept of “Theater of the Oppressed”). Both these perspectives aim to present Kagel as multifaceted composer who through his avantgarde approach abolishes canons (walls) in contemporary music and at the same time points out the barriers and limitations of the global reality. -

This Electronic Thesis Or Dissertation Has Been Downloaded from Explore Bristol Research

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from Explore Bristol Research, http://research-information.bristol.ac.uk Author: Vagopoulou, Evaggelia Title: Cultural tradition and contemporary thought in Iannis Xenakis's vocal works General rights Access to the thesis is subject to the Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial-No Derivatives 4.0 International Public License. A copy of this may be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode This license sets out your rights and the restrictions that apply to your access to the thesis so it is important you read this before proceeding. Take down policy Some pages of this thesis may have been removed for copyright restrictions prior to having it been deposited in Explore Bristol Research. However, if you have discovered material within the thesis that you consider to be unlawful e.g. breaches of copyright (either yours or that of a third party) or any other law, including but not limited to those relating to patent, trademark, confidentiality, data protection, obscenity, defamation, libel, then please contact [email protected] and include the following information in your message: •Your contact details •Bibliographic details for the item, including a URL •An outline nature of the complaint Your claim will be investigated and, where appropriate, the item in question will be removed from public view as soon as possible. Cultural Tradition and Contemporary Thought in lannis Xenakis's Vocal Works Volume I: Thesis Text Evaggelia Vagopoulou A dissertation submitted to the University of Bristol in accordancewith the degree requirements of the of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Arts, Music Department. -

Shiraz Dissertation Full 8.2.20. Final Format

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SAN DIEGO The Shiraz Arts Festival: Cultural Democracy, National Identity, and Revolution in Iranian Performance, 1967-1977 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy In Music By Joshua Jamsheed Charney Committee in charge: Professor Anthony Davis, Co-Chair Professor Jann Pasler, Co-Chair Professor Aleck Karis Professor Babak Rahimi Professor Shahrokh Yadegari 2020 © Joshua Jamsheed Charney, 2020 All rights reserved. The dissertation of Joshua Jamsheed Charney is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: _____________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________ Co-chair _____________________________________________________________ Co-Chair University of California San Diego 2020 iii EPIGRAPH Oh my Shiraz, the nonpareil of towns – The lord look after it, and keep it from decay! Hafez iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page…………………………………………………………………… iii Epigraph…………………………………………………………………………. iv Table of Contents………………………………………………………………… v Acknowledgements……………………………………………………………… vii Vita………………………………………………………………………………. viii Abstract of the Dissertation……………………………………………………… ix Introduction……………………………………………………………………… 1 Chapter 1: Festival Overview …………………………………………………… 17 Chapter 2: Cultural Democracy…………………………………………………. -

Module 2 Roleplaying Games

Module 3 Media Perspectives through Computer Games Staffan Björk Module 3 Learning Objectives ■ Describe digital and electronic games using academic game terms ■ Analyze how games are defined by technological affordances and constraints ■ Make use of and combine theoretical concepts of time, space, genre, aesthetics, fiction and gender Focuses for Module 3 ■ Computer Games ■ Affect on gameplay and experience due to the medium used to mediate the game ■ Noticeable things not focused upon ■ Boundaries of games ■ Other uses of games and gameplay ■ Experimental game genres First: schedule change ■ Lecture moved from Monday to Friday ■ Since literature is presented in it Literature ■ Arsenault, Dominic and Audrey Larochelle. From Euclidian Space to Albertian Gaze: Traditions of Visual Representation in Games Beyond the Surface. Proceedings of DiGRA 2013: DeFragging Game Studies. 2014. http://www.digra.org/digital- library/publications/from-euclidean-space-to-albertian-gaze-traditions-of-visual- representation-in-games-beyond-the-surface/ ■ Gazzard, Alison. Unlocking the Gameworld: The Rewards of Space and Time in Videogames. Game Studies, Volume 11 Issue 1 2011. http://gamestudies.org/1101/articles/gazzard_alison ■ Linderoth, J. (2012). The Effort of Being in a Fictional World: Upkeyings and Laminated Frames in MMORPGs. Symbolic Interaction, 35(4), 474-492. ■ MacCallum-Stewart, Esther. “Take That, Bitches!” Refiguring Lara Croft in Feminist Game Narratives. Game Studies, Volume 14 Issue 2 2014. http://gamestudies.org/1402/articles/maccallumstewart ■ Nitsche, M. (2008). Combining Interaction and Narrative, chapter 5 in Video Game Spaces : Image, Play, and Structure in 3D Worlds, MIT Press, 2008. ProQuest Ebook Central. https://chalmers.instructure.com/files/738674 ■ Vella, Daniel. Modelling the Semiotic Structure of Game Characters. -

Sprechen Über Neue Musik

Sprechen über Neue Musik Eine Analyse der Sekundärliteratur und Komponistenkommentare zu Pierre Boulez’ Le Marteau sans maître (1954), Karlheinz Stockhausens Gesang der Jünglinge (1956) und György Ligetis Atmosphères (1961) Dissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades der Philosophie (Dr. phil.) vorgelegt der Philosophischen Fakultät II der Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg, Institut für Musik, Abteilung Musikwissenschaft von Julia Heimerdinger ∗∗∗ Datum der Verteidigung 4. Juli 2013 Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Wolfgang Auhagen Prof. Dr. Wolfgang Hirschmann I Inhalt 1. Einleitung 1 2. Untersuchungsgegenstand und Methode 10 2.1. Textkorpora 10 2.2. Methode 12 2.2.1. Problemstellung und das Programm MAXQDA 12 2.2.2. Die Variablentabelle und die Liste der Codes 15 2.2.3. Auswertung: Analysefunktionen und Visual Tools 32 3. Pierre Boulez: Le Marteau sans maître (1954) 35 3.1. „Das Glück einer irrationalen Dimension“. Pierre Boulez’ Werkkommentare 35 3.2. Die Rätsel des Marteau sans maître 47 3.2.1. Die auffällige Sprache zu Le Marteau sans maître 58 3.2.2. Wahrnehmung und Interpretation 68 4. Karlheinz Stockhausen: Gesang der Jünglinge (elektronische Musik) (1955-1956) 85 4.1. Kontinuum. Stockhausens Werkkommentare 85 4.2. Kontinuum? Gesang der Jünglinge 95 4.2.1. Die auffällige Sprache zum Gesang der Jünglinge 101 4.2.2. Wahrnehmung und Interpretation 109 5. György Ligeti: Atmosphères (1961) 123 5.1. Von der musikalischen Vorstellung zum musikalischen Schein. Ligetis Werkkommentare 123 5.1.2. Ligetis auffällige Sprache 129 5.1.3. Wahrnehmung und Interpretation 134 5.2. Die große Vorstellung. Atmosphères 143 5.2.2. Die auffällige Sprache zu Atmosphères 155 5.2.3. -

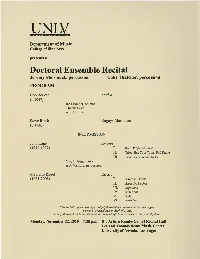

Doctoral Ensemble Recital Jeremy Meronuck, Percussion Luke Thatcher, Percussion PROGRAM

Department of Music College of Fine Arts presents a Doctoral Ensemble Recital Jeremy Meronuck, percussion Luke Thatcher, percussion PROGRAM Bob Becker Mudra (b.1947) Jack Steiner, soloist Charlie Gott A.J. Merlino Steve Reich Nagoya Marimbas (b.1936) INTERMISSION John Cage A mores (1912-1992) I. Solo: Prepared Piano II. Trio: ine Tom Toms, Pod Rattle ill. Trio: Seven Woodblocks Otto Ehling, piano A.J. Merlino, percussion Mauricio Kagel Rrrrrrr (1931-2008) I. Railroad Drama II. Ranz des Vaches III. Rigaudon IV. Rim Shot v. Ruff VI. Rutscher This recital is presented in partial fulfillment ofthe requirements for the degree Doctor ofMusical Arts in Applied Music. Jeremy Meronuck and Luke Thatcher are students ofDean Gronemeier and Timothy Jones. Monday, November 22,2010 7:30p.m. Dr. Arturo Rando-Grillot Recital Hall Lee and Thomas Beam Music Center University of Nevada, Las Vegas PROGRAM NOTES Mudra consists of music, which was originally composed to accompany the dance Mudra by choreographer Joan Phillips. Commissioned by INDE '90 and premiered in Toronto in March, 1990, as part of the DuMaurier Quay Works series, Mudra was awarded the National Art Centre Award for best collaboration between composer and choreographer. The music was subsequently edited and re-orchestrated as a concert piece for the percussion group NEXUS during May, 1990. Mudra is scored for marimba, vibraphone, songbells, glockenspiel, crotales, prepared drum and bass drum. Mudra was created, for the most part, using the "dance first" approach, in which the music is composed to fit pre-existing choreography. Thus, the rhythmic structure and overall form reflect the episodic and gestural character of the original choreography, which dealt with the conflict of traditional and modern issues in a multi-cultural urban society. -

Mark Peasley

M ark Peasley 425.518.2049 [email protected] www.ibuild3d.com Professional 3D artist and designer looking for creative opportunities. Extensive development experience on PC, Xbox, 360 and Xbox One. Expert knowledge of 3D asset creation & production. Excellent communication skills across multiple disciplines. Very adaptive to new art production pipelines and developing under tight scheduling constraints of small to AAA productions. Microsoft Art Lead for multiple track environments on Forza Motorsport 5. Involved in all Turn 10 Studio aspects of content creation, V-Ray lighting, scheduling, managing internal and Amaxra, Inc. external artists. Heavily involved in R & D of new techniques, processes and Art Lead technology to push the visual envelope. High poly & low poly workflows. Physical 2012 - Present based shader development and usage. Tools and pipeline prototyping. Digipen Institute Digital Arts Department Chair involved with planning, scheduling, and curriculum of Technology development. B.F.A. and M.F.A. program development oversight. Senior lecturer Department Chair teaching beginning through advanced 3D modeling, texturing, lighting, and Senior Lecturer rendering using 3DS Max & Maya. Taught advanced character animation and 2009 - 2012 rigging techniques using 3DS Max. Lecture and teach over 70 students on a daily basis. Responsible for establishing curriculum, syllabus and lesson plan for basic & advanced 3D, character rigging, lighting, rendering and compositing. Development of curriculum for B.F.A. & M.F.A programs. Academic Advisor for computer art majors. Microsoft Executive demo team. Designed, prototyped and developed content for a fully 3D Research Stereoscopic UI system using Kinect 3D motion input system and a custom XNA Contract Art Lead development engine. -

Holmes Electronic and Experimental Music

C H A P T E R 2 Early Electronic Music in Europe I noticed without surprise by recording the noise of things that one could perceive beyond sounds, the daily metaphors that they suggest to us. —Pierre Schaeffer Before the Tape Recorder Musique Concrète in France L’Objet Sonore—The Sound Object Origins of Musique Concrète Listen: Early Electronic Music in Europe Elektronische Musik in Germany Stockhausen’s Early Work Other Early European Studios Innovation: Electronic Music Equipment of the Studio di Fonologia Musicale (Milan, c.1960) Summary Milestones: Early Electronic Music of Europe Plate 2.1 Pierre Schaeffer operating the Pupitre d’espace (1951), the four rings of which could be used during a live performance to control the spatial distribution of electronically produced sounds using two front channels: one channel in the rear, and one overhead. (1951 © Ina/Maurice Lecardent, Ina GRM Archives) 42 EARLY HISTORY – PREDECESSORS AND PIONEERS A convergence of new technologies and a general cultural backlash against Old World arts and values made conditions favorable for the rise of electronic music in the years following World War II. Musical ideas that met with punishing repression and indiffer- ence prior to the war became less odious to a new generation of listeners who embraced futuristic advances of the atomic age. Prior to World War II, electronic music was anchored down by a reliance on live performance. Only a few composers—Varèse and Cage among them—anticipated the importance of the recording medium to the growth of electronic music. This chapter traces a technological transition from the turntable to the magnetic tape recorder as well as the transformation of electronic music from a medium of live performance to that of recorded media.