Supplement to the Music of Mauricio Kagel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Abstracts Papers Read

ABSTRACTS of- PAPERS READ at the THIRTY-FIFTH ANNUAL MEETING of the AMERICAN MUSICOLOGICAL SOCIETY SAINT LOUIS, MISSOURI DECEMBER 27-29, 1969 Contents Introductory Notes ix Opera The Role of the Neapolitan Intermezzo in the Evolution of the Symphonic Idiom Gordana Lazarevich Barnard College The Cabaletta Principle Philip Gossett · University of Chicago 2 Gluck's Treasure Chest-The Opera Telemacco Karl Geiringer · University of California, Santa Barbara 3 Liturgical Chant-East and West The Degrees of Stability in the Transmission of the Byzantine Melodies Milos Velimirovic · University of Wisconsin, Madison 5 An 8th-Century(?) Tale of the Dissemination of Musico Liturgical Practice: the Ratio decursus qui fuerunt ex auctores Lawrence A. Gushee · University of Wisconsin, Madison 6 A Byzantine Ars nova: The 14th-Century Reforms of John Koukouzeles in the Chanting of the Great Vespers Edward V. Williams . University of Kansas 7 iii Unpublished Antiphons and Antiphon Series Found in the Dodecaphony Gradual of St. Yrieix Some Notes on the Prehist Clyde W. Brockett, Jr. · University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee 9 Mark DeVoto · Unive Ist es genug? A Considerat Criticism and Stylistic Analysis-Aims, Similarities, and Differences PeterS. Odegard · Uni· Some Concrete Suggestions for More Comprehensive Style Analysis The Variation Structure in Jan LaRue · New York University 11 Philip Friedheim · Stat Binghamton An Analysis of the Beginning of the First Movement of Beethoven's Piano Sonata, Op. 8la Serialism in Latin America Leonard B. Meyer · University of Chicago 12 Juan A. Orrego-Salas · Renaissance Topics Problems in Classic Music A Severed Head: Notes on a Lost English Caput Mass Larger Formal Structures 1 Johann Christian Bach Thomas Walker · State University of New York, Buffalo 14 Marie Ann Heiberg Vos Piracy on the Italian Main-Gardane vs. -

Dante Anzolini

Music at MIT Oral History Project Dante Anzolini Interviewed by Forrest Larson March 28, 2005 Interview no. 1 Massachusetts Institute of Technology Lewis Music Library Transcribed by: Mediascribe, Clifton Park, NY. From the audio recording. Transcript Proof Reader: Lois Beattie, Jennifer Peterson Transcript Editor: Forrest Larson ©2011 Massachusetts Institute of Technology Lewis Music Library, Cambridge, MA ii Table of Contents 1. Family background (00:25—CD1 00:25) ......................................................................1 Berisso, Argentina—on languages and dialects—paternal grandfather’s passion for music— early aptitude for piano—music and soccer—on learning Italian and Chilean music 2. Early musical experiences and training (19:26—CD1 19:26) ............................................. 7 Argentina’s National Radio—self-guided study in contemporary music—decision to become a conductor—piano lessons in Berisso—Gilardo Gilardi Conservatory of Music in La Plata, Argentina—Martha Argerich—María Rosa Oubiña “Cucucha” Castro—Nikita Magaloff— Carmen Scalcione—Gerardo Gandini 3. Interest in contemporary music (38:42—CD2 00:00) .................................................14 Enrique Girardi—Pierre Boulez—Anton Webern—Charles Ives—Carl Ruggles’ Men and Mountains—Joseph Machlis—piano training at Gilardo Gilardi Conservatory of Music—private conductor training with Mariano Drago Sijanec—Hermann Scherchen—Carlos Kleiber— importance of gesture in conducting—São Paolo municipal library 4. Undergraduate education (1:05:34–CD2 26:55) -

Expanding Horizons: the International Avant-Garde, 1962-75

452 ROBYNN STILWELL Joplin, Janis. 'Me and Bobby McGee' (Columbia, 1971) i_ /Mercedes Benz' (Columbia, 1971) 17- Llttle Richard. 'Lucille' (Specialty, 1957) 'Tutti Frutti' (Specialty, 1955) Lynn, Loretta. 'The Pili' (MCA, 1975) Expanding horizons: the International 'You Ain't Woman Enough to Take My Man' (MCA, 1966) avant-garde, 1962-75 'Your Squaw Is On the Warpath' (Decca, 1969) The Marvelettes. 'Picase Mr. Postman' (Motown, 1961) RICHARD TOOP Matchbox Twenty. 'Damn' (Atlantic, 1996) Nelson, Ricky. 'Helio, Mary Lou' (Imperial, 1958) 'Traveling Man' (Imperial, 1959) Phair, Liz. 'Happy'(live, 1996) Darmstadt after Steinecke Pickett, Wilson. 'In the Midnight Hour' (Atlantic, 1965) Presley, Elvis. 'Hound Dog' (RCA, 1956) When Wolfgang Steinecke - the originator of the Darmstadt Ferienkurse - The Ravens. 'Rock All Night Long' (Mercury, 1948) died at the end of 1961, much of the increasingly fragüe spirit of collegial- Redding, Otis. 'Dock of the Bay' (Stax, 1968) ity within the Cologne/Darmstadt-centred avant-garde died with him. Boulez 'Mr. Pitiful' (Stax, 1964) and Stockhausen in particular were already fiercely competitive, and when in 'Respect'(Stax, 1965) 1960 Steinecke had assigned direction of the Darmstadt composition course Simón and Garfunkel. 'A Simple Desultory Philippic' (Columbia, 1967) to Boulez, Stockhausen had pointedly stayed away.1 Cage's work and sig- Sinatra, Frank. In the Wee SmallHoun (Capítol, 1954) Songsfor Swinging Lovers (Capítol, 1955) nificance was a constant source of acrimonious debate, and Nono's bitter Surfaris. 'Wipe Out' (Decca, 1963) opposition to himz was one reason for the Italian composer being marginal- The Temptations. 'Papa Was a Rolling Stone' (Motown, 1972) ized by the Cologne inner circle as a structuralist reactionary. -

Transgressing the Wall. Mauricio Kagel and Decanonization of the Musical Performance

Bulletin of the Transilvania University of Braşov Series VIII: Performing Arts • Vol. 13 (60) No. 2 - 2020 https://doi.org/10.31926/but.pa.2020.13.62.2.2 Transgressing the Wall. Mauricio Kagel and Decanonization of the musical performance Laurențiu BELDEAN1, Malgorzata LISECKA2 Abstract: The article discusses selected some musical concept by Maurcio Kagel (1931–2008), one of the most significant Argentinian composer. The analysis concerns two issues related to Kagel’s work. First of all, the composer’s approach to musical theatre as an artistic tool for demolishing a wall put in cultural tradition between a performer and a musical work – just like Berlin Wall which turned the politics paradigm in order to melt two political positions into one. Kagel’s negation of the structure’s coherence in traditional musical canon became the basis of his conceptualization which implies a collapse within the wall between the musical instrument and the performer. Aforementioned performer doesn’t remain in the passive role, but is engaged in the art with his whole body as authentic, vivid instrument. Secondly, this article concerns the actual threads of Kagel’s music, as he was interested in enclosing in his work contemporary social and political issues. As the context of the analyze the authors used the ideas of Paulo Freire (with his concept of the pedagogy of freedom) and Augusto Boal (with his concept of “Theater of the Oppressed”). Both these perspectives aim to present Kagel as multifaceted composer who through his avantgarde approach abolishes canons (walls) in contemporary music and at the same time points out the barriers and limitations of the global reality. -

Paz, Schoenberg, Y Abel: Una Indagación De Sus Recorridos Hacia La Atonalidad Basada En Atributos Estadísticos De La Música

Paz, Schoenberg, y Abel: una indagación de sus recorridos hacia la atonalidad basada en atributos estadísticos de la música J. Fernando Anta y Alejandro Martínez Revista Argentina de Musicología 15-16 (2014-2015), 231-250. ISSN 1660-1060 Revista de Musicología 15-16.indd 231 04/08/2016 10:16:48 p.m. 232 Revista Argentina de Musicología 2014-2015 Paz, Schoenberg, y Abel: una indagación de sus recorridos hacia la atonalidad basada en atributos estadísticos de la música Las vinculaciones existentes entre Juan Carlos Paz y Arnold Schoenberg son bien conocidas, y muy estrechas. Sin embargo, la trayectoria recorrida por Paz hacia el abandono de la tonalidad ha sido solo parcialmente documentada, y las relaciones existentes entre dicha trayectoria y aquella recorrida por Schoenberg, su referente, han sido aún menos exploradas. El objetivo del presente estudio fue clarificar es- tos dos puntos focalizando en el tipo de composición lineal de ambos compositores, particularmente en el monto de dispersión de las notas en el registro, y comparando cómo uno y otro avanzó hacia la atonalidad a través de dicho parámetro. Para ello, analizamos cómo en la melodía (vocal) de sus canciones se distribuyen y organizan los intervalos. Los resultados sugieren que, en el marco de sus canciones, los modos en que uno y otro compositor se aproximaron a la atonalidad fueron diferentes: Paz organizó la arquitectura melódica sobre niveles de dispersión menores que los utiliza- dos por Schoenberg, y atendiendo a “reglas de conducción de voces” propias de la música tonal en mayor medida que este último. Palabras clave: Juan Carlos Paz, Arnold Schoenberg, tonalidad, atonalidad, disper- sión de las alturas. -

19 by Gianmario Borio* Among the Early Sources Preserved in The

Beiträge Mauricio Kagel’s Analysis of Schoenberg’s Phantasy for Violin with Piano Accompaniment op. 47 by Gianmario Borio* Among the early sources preserved in the Mauricio Kagel Collection is a dossier dedicated to Schoenberg’s Phantasy op. 47, containing an annotated copy of the score, a series of notes on various aspects of its compositional technique, some annotated samples, and a rough draft of a text most likely intended for publication. This material can only be dated hypothetically on the basis of historical evidence. On August 7, 1953, the Phantasy was per- formed at a concert organized by the Agrupación Nueva Música, in which Kagel participated as a pianist; a fleeting reference to the first book by Allen Forte, seen at the bottom of the table of transpositions, allows us to define the dossier’s terminus post quem; lastly, the language used in the notes, considered along with their underlying topics, seems to rule out the possi- bility that they were written during his early years in Germany.1 Kagel’s analysis reveals much about the set of problems with which he was dealing during the composition of Sexteto de cuerdas and the first version of Anagra- ma.2 It also sheds light on the origin of some of the more durable premises of his thought and, on a more general level, represents a significant episode in the reception of the Phantasy itself. * This article originated as part of the project Composers Analysing Other Composers, on which I have been working for a number of years. The first results of the project were pub- lished in “L’analyse musicale comme processus d’appropriation historique: Webern à Darmstadt,” in Circuit: Musiques contemporaines, 15 (2005), no. -

Sprechen Über Neue Musik

Sprechen über Neue Musik Eine Analyse der Sekundärliteratur und Komponistenkommentare zu Pierre Boulez’ Le Marteau sans maître (1954), Karlheinz Stockhausens Gesang der Jünglinge (1956) und György Ligetis Atmosphères (1961) Dissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades der Philosophie (Dr. phil.) vorgelegt der Philosophischen Fakultät II der Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg, Institut für Musik, Abteilung Musikwissenschaft von Julia Heimerdinger ∗∗∗ Datum der Verteidigung 4. Juli 2013 Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Wolfgang Auhagen Prof. Dr. Wolfgang Hirschmann I Inhalt 1. Einleitung 1 2. Untersuchungsgegenstand und Methode 10 2.1. Textkorpora 10 2.2. Methode 12 2.2.1. Problemstellung und das Programm MAXQDA 12 2.2.2. Die Variablentabelle und die Liste der Codes 15 2.2.3. Auswertung: Analysefunktionen und Visual Tools 32 3. Pierre Boulez: Le Marteau sans maître (1954) 35 3.1. „Das Glück einer irrationalen Dimension“. Pierre Boulez’ Werkkommentare 35 3.2. Die Rätsel des Marteau sans maître 47 3.2.1. Die auffällige Sprache zu Le Marteau sans maître 58 3.2.2. Wahrnehmung und Interpretation 68 4. Karlheinz Stockhausen: Gesang der Jünglinge (elektronische Musik) (1955-1956) 85 4.1. Kontinuum. Stockhausens Werkkommentare 85 4.2. Kontinuum? Gesang der Jünglinge 95 4.2.1. Die auffällige Sprache zum Gesang der Jünglinge 101 4.2.2. Wahrnehmung und Interpretation 109 5. György Ligeti: Atmosphères (1961) 123 5.1. Von der musikalischen Vorstellung zum musikalischen Schein. Ligetis Werkkommentare 123 5.1.2. Ligetis auffällige Sprache 129 5.1.3. Wahrnehmung und Interpretation 134 5.2. Die große Vorstellung. Atmosphères 143 5.2.2. Die auffällige Sprache zu Atmosphères 155 5.2.3. -

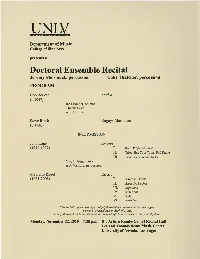

Doctoral Ensemble Recital Jeremy Meronuck, Percussion Luke Thatcher, Percussion PROGRAM

Department of Music College of Fine Arts presents a Doctoral Ensemble Recital Jeremy Meronuck, percussion Luke Thatcher, percussion PROGRAM Bob Becker Mudra (b.1947) Jack Steiner, soloist Charlie Gott A.J. Merlino Steve Reich Nagoya Marimbas (b.1936) INTERMISSION John Cage A mores (1912-1992) I. Solo: Prepared Piano II. Trio: ine Tom Toms, Pod Rattle ill. Trio: Seven Woodblocks Otto Ehling, piano A.J. Merlino, percussion Mauricio Kagel Rrrrrrr (1931-2008) I. Railroad Drama II. Ranz des Vaches III. Rigaudon IV. Rim Shot v. Ruff VI. Rutscher This recital is presented in partial fulfillment ofthe requirements for the degree Doctor ofMusical Arts in Applied Music. Jeremy Meronuck and Luke Thatcher are students ofDean Gronemeier and Timothy Jones. Monday, November 22,2010 7:30p.m. Dr. Arturo Rando-Grillot Recital Hall Lee and Thomas Beam Music Center University of Nevada, Las Vegas PROGRAM NOTES Mudra consists of music, which was originally composed to accompany the dance Mudra by choreographer Joan Phillips. Commissioned by INDE '90 and premiered in Toronto in March, 1990, as part of the DuMaurier Quay Works series, Mudra was awarded the National Art Centre Award for best collaboration between composer and choreographer. The music was subsequently edited and re-orchestrated as a concert piece for the percussion group NEXUS during May, 1990. Mudra is scored for marimba, vibraphone, songbells, glockenspiel, crotales, prepared drum and bass drum. Mudra was created, for the most part, using the "dance first" approach, in which the music is composed to fit pre-existing choreography. Thus, the rhythmic structure and overall form reflect the episodic and gestural character of the original choreography, which dealt with the conflict of traditional and modern issues in a multi-cultural urban society. -

Holmes Electronic and Experimental Music

C H A P T E R 2 Early Electronic Music in Europe I noticed without surprise by recording the noise of things that one could perceive beyond sounds, the daily metaphors that they suggest to us. —Pierre Schaeffer Before the Tape Recorder Musique Concrète in France L’Objet Sonore—The Sound Object Origins of Musique Concrète Listen: Early Electronic Music in Europe Elektronische Musik in Germany Stockhausen’s Early Work Other Early European Studios Innovation: Electronic Music Equipment of the Studio di Fonologia Musicale (Milan, c.1960) Summary Milestones: Early Electronic Music of Europe Plate 2.1 Pierre Schaeffer operating the Pupitre d’espace (1951), the four rings of which could be used during a live performance to control the spatial distribution of electronically produced sounds using two front channels: one channel in the rear, and one overhead. (1951 © Ina/Maurice Lecardent, Ina GRM Archives) 42 EARLY HISTORY – PREDECESSORS AND PIONEERS A convergence of new technologies and a general cultural backlash against Old World arts and values made conditions favorable for the rise of electronic music in the years following World War II. Musical ideas that met with punishing repression and indiffer- ence prior to the war became less odious to a new generation of listeners who embraced futuristic advances of the atomic age. Prior to World War II, electronic music was anchored down by a reliance on live performance. Only a few composers—Varèse and Cage among them—anticipated the importance of the recording medium to the growth of electronic music. This chapter traces a technological transition from the turntable to the magnetic tape recorder as well as the transformation of electronic music from a medium of live performance to that of recorded media. -

Música En La España Contemporánea (Interuniversitario) (Mención De Calidad)

PROGRAMA DE DOCTORADO: Música en la España Contemporánea (Interuniversitario) (Mención de calidad) Cruce de modernidades. La música para piano en España entre 1958 y 1982 Miriam Mancheño Delgado ÍNDICE GENERAL Índice General Agradecimientos 11 Resumen 17 Abstract 21 Introducción 1. JUSTIFICACIÓN Y OBJETIVOS 27 2. ESTADO DE LA CUESTIÓN 30 3. METODOLOGÍA 37 4. FUENTES 42 Capítulo I: España 1958-1982 1. ESPAÑA 1958-1982: CIRCUNSTANCIAS HISTÓRICAS Y CONTEXTO MUSICAL 49 1.1. Circunstancias históricas 49 1.2. Contexto musical 52 2. EN TORNO A LAS GENERACIONES MUSICALES 69 3. LA PRODUCCIÓN PARA PIANO 78 3.1. Cruce de modernidades 80 4. INTÉRPRETES 85 Capítulo II: Avanzar mirando al pasado: formalismo y neotonalidad 1. CONTINUIDADES 97 2. EL APEGO A LAS FORMAS TRADICIONALES 102 2.1. La sonata como referente de la tradición musical 102 2.2. El retorno al renacimiento y al barroco 111 2.3. Ciclos de piezas breves 121 ÍNDICE GENERAL 3. FOLKLORISMO 128 3.1. Utilización de citas 129 3.2. Inspiración de modelos populares 139 Capítulo III: Dodecafonismo y expresividad 1. RECEPCIÓN E INCIDENCIA DE LA II ESCUELA DE VIENA EN LA SEGUNDA MITAD DEL SIGLO XX 149 2. EL DISEÑO DE LAS SERIES EN LA MÚSICA ESPAÑOLA PARA PIANO 161 2.1. Construcción de las series 161 2.1.1. Agrupaciones simétricas 162 2.1.2. Agrupaciones parcialmente simétricas 164 2.1.3. Agrupaciones asimétricas 164 2.2. Exposición de la serie 165 2.3. La presencia de estructuras tonales 167 3. DODECAFONISMO Y SERIALISMO COMO LENGUAJE PROPIO 169 3.1. Rodolfo Halffter 170 3.1.1. -

Vendredi 10 Février Ensemble Intercontemporain Ensemble In

Roch-Olivier Maistre, Président du Conseil d’administration Laurent Bayle, Directeur général Vendredi 10 février Ensemble intercontemporain Dans le cadre du cycle Des pieds et des mains Du 10 au 12 février Vendredi 10 février 10 Vendredi | Vous avez la possibilité de consulter les notes de programme en ligne, 2 jours avant chaque concert, à l’adresse suivante : www.citedelamusique.fr Ensemble intercontemporain Ensemble intercontemporain Cycle Des pieds et des mains L’Ensemble intercontemporain présente deux concerts dans le cadre du cycle Des pieds et des mains à la Cité de la musique. Inori (un mot japonais qui signie « invocation, adoration ») est une expérience totale. La mimique quasi dansée des deux « solistes » emprunte le code de ses gestes de prière à diverses religions du monde. À chaque mouvement des mains correspond une note : Inori est en 1974 l’une des premières pièces de Stockhausen à se fonder sur une « formule », sorte d’hyper-mélodie qui non seulement est entendue comme telle mais se retrouve pour ainsi dire étirée à l’échelle de l’œuvre dans son entier, dont elle dicte et caractérise les diérentes parties. Enn, chacune des sections d’Inori se concentre sur un aspect du discours musical – dans l’ordre : rythme, dynamique, mélodie, harmonie et polyphonie –, si bien que la partition, selon le compositeur, « se développe comme une histoire de la musique » reparcourue en accéléré, depuis l’origine jusqu’à nos jours. Dans le saisissant Pas de cinq de Mauricio Kagel, composé en 1965, les cinq exécutants, munis d’une canne, parcourent et sillonnent une surface délimitée en forme de pentagone couvert de diérents matériaux. -

Music Theatre

11 Music Theatre In the 1950s, when attention generally was fi xed on musical funda- mentals, few young composers wanted to work in the theatre. Indeed, to express that want was almost enough, as in the case of Henze, to separate oneself from the avant-garde. Boulez, while earning his living as a theatre musician, kept his creative work almost entirely separate until near the end of his time with Jean-Louis Barrault, when he wrote a score for a production of the Oresteia (1955), and even that work he never published or otherwise accepted into his offi cial oeuvre. Things began to change on both sides of the Atlantic around 1960, the year when Cage produced his Theatre Piece and Nono began Intolleranza, the fi rst opera from inside the Darmstadt circle. However, opportunities to present new operas remained rare: even in Germany, where there were dozens of theatres producing opera, and where the new operas of the 1920s had found support, the Hamburg State Opera, under the direction of Rolf Liebermann from 1959 to 1973, was unusual in com- missioning works from Penderecki, Kagel, and others. Also, most com- posers who had lived through the analytical 1950s were suspicious of standard genres, and when they turned to dramatic composition it was in the interests of new musical-theatrical forms that sprang from new material rather than from what appeared a long-moribund tradition. (It was already a truism that no opera since Turandot had joined the regular international repertory. What was not realized until the late 1970s was that there could be a living operatic culture based on rapid obsolescence.) Meanwhile, Cage’s work—especially the piano pieces he 190 Music Theatre 191 had written for Tudor in the 1950s—had shown that no new kind of music theatre was necessary, that all music is by nature theatre, that all performance is drama.