Transgressing the Wall. Mauricio Kagel and Decanonization of the Musical Performance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Expanding Horizons: the International Avant-Garde, 1962-75

452 ROBYNN STILWELL Joplin, Janis. 'Me and Bobby McGee' (Columbia, 1971) i_ /Mercedes Benz' (Columbia, 1971) 17- Llttle Richard. 'Lucille' (Specialty, 1957) 'Tutti Frutti' (Specialty, 1955) Lynn, Loretta. 'The Pili' (MCA, 1975) Expanding horizons: the International 'You Ain't Woman Enough to Take My Man' (MCA, 1966) avant-garde, 1962-75 'Your Squaw Is On the Warpath' (Decca, 1969) The Marvelettes. 'Picase Mr. Postman' (Motown, 1961) RICHARD TOOP Matchbox Twenty. 'Damn' (Atlantic, 1996) Nelson, Ricky. 'Helio, Mary Lou' (Imperial, 1958) 'Traveling Man' (Imperial, 1959) Phair, Liz. 'Happy'(live, 1996) Darmstadt after Steinecke Pickett, Wilson. 'In the Midnight Hour' (Atlantic, 1965) Presley, Elvis. 'Hound Dog' (RCA, 1956) When Wolfgang Steinecke - the originator of the Darmstadt Ferienkurse - The Ravens. 'Rock All Night Long' (Mercury, 1948) died at the end of 1961, much of the increasingly fragüe spirit of collegial- Redding, Otis. 'Dock of the Bay' (Stax, 1968) ity within the Cologne/Darmstadt-centred avant-garde died with him. Boulez 'Mr. Pitiful' (Stax, 1964) and Stockhausen in particular were already fiercely competitive, and when in 'Respect'(Stax, 1965) 1960 Steinecke had assigned direction of the Darmstadt composition course Simón and Garfunkel. 'A Simple Desultory Philippic' (Columbia, 1967) to Boulez, Stockhausen had pointedly stayed away.1 Cage's work and sig- Sinatra, Frank. In the Wee SmallHoun (Capítol, 1954) Songsfor Swinging Lovers (Capítol, 1955) nificance was a constant source of acrimonious debate, and Nono's bitter Surfaris. 'Wipe Out' (Decca, 1963) opposition to himz was one reason for the Italian composer being marginal- The Temptations. 'Papa Was a Rolling Stone' (Motown, 1972) ized by the Cologne inner circle as a structuralist reactionary. -

Sprechen Über Neue Musik

Sprechen über Neue Musik Eine Analyse der Sekundärliteratur und Komponistenkommentare zu Pierre Boulez’ Le Marteau sans maître (1954), Karlheinz Stockhausens Gesang der Jünglinge (1956) und György Ligetis Atmosphères (1961) Dissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades der Philosophie (Dr. phil.) vorgelegt der Philosophischen Fakultät II der Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg, Institut für Musik, Abteilung Musikwissenschaft von Julia Heimerdinger ∗∗∗ Datum der Verteidigung 4. Juli 2013 Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Wolfgang Auhagen Prof. Dr. Wolfgang Hirschmann I Inhalt 1. Einleitung 1 2. Untersuchungsgegenstand und Methode 10 2.1. Textkorpora 10 2.2. Methode 12 2.2.1. Problemstellung und das Programm MAXQDA 12 2.2.2. Die Variablentabelle und die Liste der Codes 15 2.2.3. Auswertung: Analysefunktionen und Visual Tools 32 3. Pierre Boulez: Le Marteau sans maître (1954) 35 3.1. „Das Glück einer irrationalen Dimension“. Pierre Boulez’ Werkkommentare 35 3.2. Die Rätsel des Marteau sans maître 47 3.2.1. Die auffällige Sprache zu Le Marteau sans maître 58 3.2.2. Wahrnehmung und Interpretation 68 4. Karlheinz Stockhausen: Gesang der Jünglinge (elektronische Musik) (1955-1956) 85 4.1. Kontinuum. Stockhausens Werkkommentare 85 4.2. Kontinuum? Gesang der Jünglinge 95 4.2.1. Die auffällige Sprache zum Gesang der Jünglinge 101 4.2.2. Wahrnehmung und Interpretation 109 5. György Ligeti: Atmosphères (1961) 123 5.1. Von der musikalischen Vorstellung zum musikalischen Schein. Ligetis Werkkommentare 123 5.1.2. Ligetis auffällige Sprache 129 5.1.3. Wahrnehmung und Interpretation 134 5.2. Die große Vorstellung. Atmosphères 143 5.2.2. Die auffällige Sprache zu Atmosphères 155 5.2.3. -

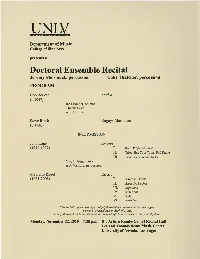

Doctoral Ensemble Recital Jeremy Meronuck, Percussion Luke Thatcher, Percussion PROGRAM

Department of Music College of Fine Arts presents a Doctoral Ensemble Recital Jeremy Meronuck, percussion Luke Thatcher, percussion PROGRAM Bob Becker Mudra (b.1947) Jack Steiner, soloist Charlie Gott A.J. Merlino Steve Reich Nagoya Marimbas (b.1936) INTERMISSION John Cage A mores (1912-1992) I. Solo: Prepared Piano II. Trio: ine Tom Toms, Pod Rattle ill. Trio: Seven Woodblocks Otto Ehling, piano A.J. Merlino, percussion Mauricio Kagel Rrrrrrr (1931-2008) I. Railroad Drama II. Ranz des Vaches III. Rigaudon IV. Rim Shot v. Ruff VI. Rutscher This recital is presented in partial fulfillment ofthe requirements for the degree Doctor ofMusical Arts in Applied Music. Jeremy Meronuck and Luke Thatcher are students ofDean Gronemeier and Timothy Jones. Monday, November 22,2010 7:30p.m. Dr. Arturo Rando-Grillot Recital Hall Lee and Thomas Beam Music Center University of Nevada, Las Vegas PROGRAM NOTES Mudra consists of music, which was originally composed to accompany the dance Mudra by choreographer Joan Phillips. Commissioned by INDE '90 and premiered in Toronto in March, 1990, as part of the DuMaurier Quay Works series, Mudra was awarded the National Art Centre Award for best collaboration between composer and choreographer. The music was subsequently edited and re-orchestrated as a concert piece for the percussion group NEXUS during May, 1990. Mudra is scored for marimba, vibraphone, songbells, glockenspiel, crotales, prepared drum and bass drum. Mudra was created, for the most part, using the "dance first" approach, in which the music is composed to fit pre-existing choreography. Thus, the rhythmic structure and overall form reflect the episodic and gestural character of the original choreography, which dealt with the conflict of traditional and modern issues in a multi-cultural urban society. -

Holmes Electronic and Experimental Music

C H A P T E R 2 Early Electronic Music in Europe I noticed without surprise by recording the noise of things that one could perceive beyond sounds, the daily metaphors that they suggest to us. —Pierre Schaeffer Before the Tape Recorder Musique Concrète in France L’Objet Sonore—The Sound Object Origins of Musique Concrète Listen: Early Electronic Music in Europe Elektronische Musik in Germany Stockhausen’s Early Work Other Early European Studios Innovation: Electronic Music Equipment of the Studio di Fonologia Musicale (Milan, c.1960) Summary Milestones: Early Electronic Music of Europe Plate 2.1 Pierre Schaeffer operating the Pupitre d’espace (1951), the four rings of which could be used during a live performance to control the spatial distribution of electronically produced sounds using two front channels: one channel in the rear, and one overhead. (1951 © Ina/Maurice Lecardent, Ina GRM Archives) 42 EARLY HISTORY – PREDECESSORS AND PIONEERS A convergence of new technologies and a general cultural backlash against Old World arts and values made conditions favorable for the rise of electronic music in the years following World War II. Musical ideas that met with punishing repression and indiffer- ence prior to the war became less odious to a new generation of listeners who embraced futuristic advances of the atomic age. Prior to World War II, electronic music was anchored down by a reliance on live performance. Only a few composers—Varèse and Cage among them—anticipated the importance of the recording medium to the growth of electronic music. This chapter traces a technological transition from the turntable to the magnetic tape recorder as well as the transformation of electronic music from a medium of live performance to that of recorded media. -

Supplement to the Music of Mauricio Kagel

Heile, Bjorn (2014) Supplement to the Music of Mauricio Kagel. Copyright © 2014 The Author Available under License Creative Commons Attribution Non-commercial No Derivatives. http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/96021/ Deposited on: 14 August 2014 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk Supplement To The Music of Mauricio Kagel (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2006) Björn Heile University of Glasgow Edition 1.0 Glasgow, August 2014 Table of Contents Illustrations ............................................................................................................................................ iii About this Publication ............................................................................................................................ iv Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................................. v Errata ...................................................................................................................................................... vi Early Work and Career ............................................................................................................................ 1 Dodecaphony ........................................................................................................................................ 34 The Late Work ...................................................................................................................................... -

Vendredi 10 Février Ensemble Intercontemporain Ensemble In

Roch-Olivier Maistre, Président du Conseil d’administration Laurent Bayle, Directeur général Vendredi 10 février Ensemble intercontemporain Dans le cadre du cycle Des pieds et des mains Du 10 au 12 février Vendredi 10 février 10 Vendredi | Vous avez la possibilité de consulter les notes de programme en ligne, 2 jours avant chaque concert, à l’adresse suivante : www.citedelamusique.fr Ensemble intercontemporain Ensemble intercontemporain Cycle Des pieds et des mains L’Ensemble intercontemporain présente deux concerts dans le cadre du cycle Des pieds et des mains à la Cité de la musique. Inori (un mot japonais qui signie « invocation, adoration ») est une expérience totale. La mimique quasi dansée des deux « solistes » emprunte le code de ses gestes de prière à diverses religions du monde. À chaque mouvement des mains correspond une note : Inori est en 1974 l’une des premières pièces de Stockhausen à se fonder sur une « formule », sorte d’hyper-mélodie qui non seulement est entendue comme telle mais se retrouve pour ainsi dire étirée à l’échelle de l’œuvre dans son entier, dont elle dicte et caractérise les diérentes parties. Enn, chacune des sections d’Inori se concentre sur un aspect du discours musical – dans l’ordre : rythme, dynamique, mélodie, harmonie et polyphonie –, si bien que la partition, selon le compositeur, « se développe comme une histoire de la musique » reparcourue en accéléré, depuis l’origine jusqu’à nos jours. Dans le saisissant Pas de cinq de Mauricio Kagel, composé en 1965, les cinq exécutants, munis d’une canne, parcourent et sillonnent une surface délimitée en forme de pentagone couvert de diérents matériaux. -

Music Theatre

11 Music Theatre In the 1950s, when attention generally was fi xed on musical funda- mentals, few young composers wanted to work in the theatre. Indeed, to express that want was almost enough, as in the case of Henze, to separate oneself from the avant-garde. Boulez, while earning his living as a theatre musician, kept his creative work almost entirely separate until near the end of his time with Jean-Louis Barrault, when he wrote a score for a production of the Oresteia (1955), and even that work he never published or otherwise accepted into his offi cial oeuvre. Things began to change on both sides of the Atlantic around 1960, the year when Cage produced his Theatre Piece and Nono began Intolleranza, the fi rst opera from inside the Darmstadt circle. However, opportunities to present new operas remained rare: even in Germany, where there were dozens of theatres producing opera, and where the new operas of the 1920s had found support, the Hamburg State Opera, under the direction of Rolf Liebermann from 1959 to 1973, was unusual in com- missioning works from Penderecki, Kagel, and others. Also, most com- posers who had lived through the analytical 1950s were suspicious of standard genres, and when they turned to dramatic composition it was in the interests of new musical-theatrical forms that sprang from new material rather than from what appeared a long-moribund tradition. (It was already a truism that no opera since Turandot had joined the regular international repertory. What was not realized until the late 1970s was that there could be a living operatic culture based on rapid obsolescence.) Meanwhile, Cage’s work—especially the piano pieces he 190 Music Theatre 191 had written for Tudor in the 1950s—had shown that no new kind of music theatre was necessary, that all music is by nature theatre, that all performance is drama. -

From Kotoński to Duchnowski. Polish Electroacoustic Music

MIECZYSŁAW KOMINEK (Warszawa) From Kotoński to Duchnowski. Polish electroacoustic music ABSTRACT: Founded in November 1957, the Experimental Studio of Polish Radio (SEPR) was the fifth electronic music studio in Europe and the seventh in the world. It was an extraordinary phenomenon in the reality of the People’s Poland of those times, equally exceptional as the Warsaw Autumn International Festival of Contemporary Music, established around the same time - in 1956. Both these ‘institutions’ would be of fundamental significance for contemporary Polish music, and they would collabo rate closely with one another. But the history of Polish electroacoustic music would to a large extent be the history of the Experimental Studio. The first autonomous work for tape in Poland was Włodzimierz Kotoñski’s Etiuda konkretna (na jedno uderzenie w talerz) [Concrete study (for a single strike of a cymbal)], completed in November 1958. It was performed at the Warsaw Autumn in i960, and from then on electroacoustic music was a fixture at the festival, even a marker of the festival’s ‘modernity’, up to 2002 - the year when the last special ‘con cert of electroacoustic music’ appeared on the programme. In 2004, the SEPR ceased its activities, but thanks to computers, every composer can now have a studio at home. There are also thriving electroacoustic studios at music academies, with the Wroclaw studio to the fore, founded in 1998 by Stanisław Krupowicz, the leading light of which became Cezary Duchnowski. Also established in Wroclaw, in 2005, was the biennial International Festival of Electroacoustic Music ‘Música Electrónica Nova’. KEYWORDS: electroacoustic music, electronic music, concrete music, music for tape, generators, experimental Studio of Polish Radio, “Warsaw Autumn” International Festival of Contemporary Music, live electronic, synthesisers, computer music The beginnings of electroacoustic music can be sought in works scored for, or including, electric instruments. -

Gastón Solnicki on Mauricio Kagel Synopsis Perimental Center of the Teatro Colón) for the Celebration of the Composer’S 75Th Anniversary

Gastón Solnicki on Mauricio Kagel Synopsis perimental Center of the Teatro Colón) for the celebration of the composer’s 75th anniversary. 111 cyclists reach famed opera house Teatro This festival achieved a new visit from Kagel to Colón to welcome Mauricio Kagel (1931-2008), Argentina after a thirty year absence. For the one of the great composers of the 20th Century, ensemble this meant the satisfaction of working who was born in Argentina, but left the country intensively with him rehearsing for the opening and settled in Germany in 1957. However, his concert at the Colón Theatre in Buenos Aires. adventurous music remained an inspiration to All this process has been recorded in süden, the a number of forward-thinking Argentinean mu- film by Gastón Solnicki. sicians, and in 2006 he returned to Buenos Aires Afterwards, the ensemble began working on for a Kagel festival, where he was to direct a ma- other music beside pieces of Kagel and record- jor concert by the Buenos Aires Philharmonic, ed a CD with a retrospective of Argentine com- but also worked with a group of young and ea- poser Gerardo Gandini. ger musicians advocated to his repertoire, the In the present time, Ensamble Süden keeps of- Ensamble Süden. Filmmaker Gaston Solnicki was fering several contemporary music concerts in on hand to capture Kagel's visit on film, and the Buenos Aires. documentary süden chronicles the composer's efforts in working directly with the musicians as Mauricio Kagel well as reflecting the situation of modern music in Argentina as such. The film surprises for its Mauricio Kagel was born in Buenos Aires capacity to captivate even those who are not on the 24th December of 1931, into a Jewish interested in contemporary music. -

Slee Lecture Reciatals Catalog 1957-1976

University at Buffalo Music Library OCTOBER 10, 1957 Performed in Baird Recital Hall SLR 1 Lecture: Introduction to the contemporary idiom Lecturer: Aaron Copland SLR 2 Composer: Debussy, Claude Title: Preludes. Book II, No. 2, 12 Performer(s): Allen Giles, piano Duration: 6:48 SLR 3 Composer: Bartók, Béla Title: Bagatelles, op. 6. no. 13, 1 Performer(s): Livingston Gearhart, piano Duration: 2:51 SLR 4 Composer: Stravinsky, Igor Title: Five easy pieces Performer(s): Livingston Gearhart, Carol Wolf, pianos Duration: 5:08 SLR 5 Composer: Schönberg, Arnold Title: Pierrot Lunaire, op. 21. No. 1, 4, 7, 9 Performer(s): Dorothy Rosenberger, soprano; Robert Mols, flute; Allen Sigel, clarinet; Harry Taub, violin; Dorris Jane Dugan-Baird, violoncello; Cameron Baird, piano Duration: 6:25 NOVEMBER 14, 1957 Performed in Baird Recital Hall SLR 6 Lecture: Music of the twenties Lecturer: Aaron Copland SLR 7 Composer: Milhaud, Darius Title: The rape of Europa Performer(s): Dorothy Rosenberger, Deok X. Koe, Vehan Khanzadian, Richard Siegel, principal roles; Unnamed chorus and orchestra; David G. Gooding, conductor Duration: 2:39 NB: Only first part of opera recorded SLR 8 Composer: Poulenc, Francis Title: Le bestaire Performer(s): Toni Packer, alto; David G. Gooding, piano Duration: 4:25 SLR 9 Composer: Stravinsky, Igor Title: Suite italienne. Introduzione, Gavotta, Finale Performer(s): Pamela Gearhart, violin; Livingston Gearhart, piano Duration: 6:55 SLR 10 Composer: Hindemith, Paul Title: Das Marienleben, 1948. 1, 5, 11, 15 Performer(s): Dorothy Rosenberger, soprano; Squire Haskin, piano Duration: 10:12 SLR 11 Composer: Berg, Alban Title: Vier Stücke für Klarinette und Klavier, op. -

Karlheinz Stockhausen's Stage Cycle Licht. Musical Theatre of the World

Interdisciplinary Studies in Musicology 8,2009 © Department o f Musicology, Adam Mickiewicz University, Poznan, Poland AGNIESZKA DRAUS (Krakow) Karlheinz Stockhausen’s stage cycle Licht. Musical theatre of the world ABSTRACT: The main idea of the paper is a presentation of the stage cycle Licht, ab sorbing the composer for over one-third of his active creative life. The question arises as to the generic affiliation of Stockhausen’s opus magnum: close to operatic works by Luciano Berio and Mauricio Kagel or to pop productions of works by Philip Glass? Analysing the subject matter and content of Licht, as well as its message and the means of expression employed, it is difficult not to discern the unification, within a single work, of what might appear to be contrasting musical genres and kinds of thea tre (mystery play, expressionist drama, happening). It is worth remembering that the composer himself does not employ any specific generic term except for Opernzyklus. He often, however, refers to the forms and genres of theatre, cultivated in many differ ent parts of the world, which have inspired him (e.g. in Malaysia, Japan, Bali, the USA), and he admits to the evolution of his views on faith. Can the substance of Licht be reduced to a common denominator? Can the heptalogy be called ‘sacred’ theatre? Or - on the contrary - an extremely profane, ‘pagan’ avant-garde spectacle? KEYWORDS: pitch, Karlheinz Stockhausen, stage-cycle, Licht, world-theatre, The Urantia Book, Michael, Eva, Lucifer, formula-composition, Hans Urs von Balthasar Karlheinz Stockhausen composed a total of around 360 works, minor and monumental, vocal and instrumental, in a variety of forms and genres. -

Swiss Chamber Soloists

www.fbbva.es www.neos‐music.com COLLECTION BBVA FOUNDATION ‐ NEOS Alberto Ginastera Popol Vuh ⋅ Cantata para América Mágica The WDR SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA COLOGNE (WDR Sinfonieorchester Köln) was founded in 1947 by what was then Northwest‐German Radio as the broadcaster’s own orchestra. It has worked and recorded with conductors of the stature of Otto Klemperer, Sir Georg Solti, Dimitri Mitropoulos, Herbert von Karajan, and Claudio Abbado, giving some forty concerts each season in the Cologne Philharmonic and West‐German Radio’s broadcasting region. It has also toured Europe and the Far East, becoming the first German orchestra to perform all of Mahler symphonies in Tokyo (under Gary Bertini, 1990–91). Besides the classical‐ romantic repertoire, it cultivates the music of the 20th and 21st centuries and has given world or German premières of works by Hans Werner Henze, Mauricio Kagel, Luciano Berio, Luigi Nono, Bernd Alois Zimmermann, and Karlheinz Stockhausen. Since the 1997/98 season its principal conductor has been Semyon Bychkov. RAYANNE DUPUIS was born in Canada and studied at the State University of New York, Yale University, and the University of Toronto. She is a member of the Canadian Opera Company Ensemble Studio and has sung many roles, including Laura (Luisa Miller), Destino & L’infea (La Calisto), Karolka (Jenufa), Echo (Ariadne auf Naxos), The Cock (The Cunning Little Vixen), and Helen in the première of Red Emma by Gary Kulesha. In 1998 she gave her European début as Marguerite in Arthur Honegger’s Jeanne d’Arc au bûcher at the Comédie de Clermont‐Ferrand. She has sung the title role in Lulu, Blanche de la Force in Dialogues des Carmélites, and the title role in the eponymous opera Jackie O by the American composer Michael Daugherty at the Opéra Théâtre de Metz.