University of Cincinnati

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Expanding Horizons: the International Avant-Garde, 1962-75

452 ROBYNN STILWELL Joplin, Janis. 'Me and Bobby McGee' (Columbia, 1971) i_ /Mercedes Benz' (Columbia, 1971) 17- Llttle Richard. 'Lucille' (Specialty, 1957) 'Tutti Frutti' (Specialty, 1955) Lynn, Loretta. 'The Pili' (MCA, 1975) Expanding horizons: the International 'You Ain't Woman Enough to Take My Man' (MCA, 1966) avant-garde, 1962-75 'Your Squaw Is On the Warpath' (Decca, 1969) The Marvelettes. 'Picase Mr. Postman' (Motown, 1961) RICHARD TOOP Matchbox Twenty. 'Damn' (Atlantic, 1996) Nelson, Ricky. 'Helio, Mary Lou' (Imperial, 1958) 'Traveling Man' (Imperial, 1959) Phair, Liz. 'Happy'(live, 1996) Darmstadt after Steinecke Pickett, Wilson. 'In the Midnight Hour' (Atlantic, 1965) Presley, Elvis. 'Hound Dog' (RCA, 1956) When Wolfgang Steinecke - the originator of the Darmstadt Ferienkurse - The Ravens. 'Rock All Night Long' (Mercury, 1948) died at the end of 1961, much of the increasingly fragüe spirit of collegial- Redding, Otis. 'Dock of the Bay' (Stax, 1968) ity within the Cologne/Darmstadt-centred avant-garde died with him. Boulez 'Mr. Pitiful' (Stax, 1964) and Stockhausen in particular were already fiercely competitive, and when in 'Respect'(Stax, 1965) 1960 Steinecke had assigned direction of the Darmstadt composition course Simón and Garfunkel. 'A Simple Desultory Philippic' (Columbia, 1967) to Boulez, Stockhausen had pointedly stayed away.1 Cage's work and sig- Sinatra, Frank. In the Wee SmallHoun (Capítol, 1954) Songsfor Swinging Lovers (Capítol, 1955) nificance was a constant source of acrimonious debate, and Nono's bitter Surfaris. 'Wipe Out' (Decca, 1963) opposition to himz was one reason for the Italian composer being marginal- The Temptations. 'Papa Was a Rolling Stone' (Motown, 1972) ized by the Cologne inner circle as a structuralist reactionary. -

Transgressing the Wall. Mauricio Kagel and Decanonization of the Musical Performance

Bulletin of the Transilvania University of Braşov Series VIII: Performing Arts • Vol. 13 (60) No. 2 - 2020 https://doi.org/10.31926/but.pa.2020.13.62.2.2 Transgressing the Wall. Mauricio Kagel and Decanonization of the musical performance Laurențiu BELDEAN1, Malgorzata LISECKA2 Abstract: The article discusses selected some musical concept by Maurcio Kagel (1931–2008), one of the most significant Argentinian composer. The analysis concerns two issues related to Kagel’s work. First of all, the composer’s approach to musical theatre as an artistic tool for demolishing a wall put in cultural tradition between a performer and a musical work – just like Berlin Wall which turned the politics paradigm in order to melt two political positions into one. Kagel’s negation of the structure’s coherence in traditional musical canon became the basis of his conceptualization which implies a collapse within the wall between the musical instrument and the performer. Aforementioned performer doesn’t remain in the passive role, but is engaged in the art with his whole body as authentic, vivid instrument. Secondly, this article concerns the actual threads of Kagel’s music, as he was interested in enclosing in his work contemporary social and political issues. As the context of the analyze the authors used the ideas of Paulo Freire (with his concept of the pedagogy of freedom) and Augusto Boal (with his concept of “Theater of the Oppressed”). Both these perspectives aim to present Kagel as multifaceted composer who through his avantgarde approach abolishes canons (walls) in contemporary music and at the same time points out the barriers and limitations of the global reality. -

A More Attractive ‘Way of Getting Things Done’ Freedom, Collaboration and Compositional Paradox in British Improvised and Experimental Music 1965-75

A more attractive ‘way of getting things done’ freedom, collaboration and compositional paradox in British improvised and experimental music 1965-75 Simon H. Fell A thesis submitted to the University of Huddersfield in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Huddersfield September 2017 copyright statement i. The author of this thesis (including any appendices and/or schedules to this thesis) owns any copyright in it (the “Copyright”) and he has given The University of Huddersfield the right to use such Copyright for any administrative, promotional, educational and/or teaching purposes. ii. Copies of this thesis, either in full or in extracts, may be made only in accordance with the regulations of the University Library. Details of these regulations may be obtained from the Librarian. This page must form part of any such copies made. iii. The ownership of any patents, designs, trade marks and any and all other intellectual property rights except for the Copyright (the “Intellectual Property Rights”) and any reproductions of copyright works, for example graphs and tables (“Reproductions”), which may be described in this thesis, may not be owned by the author and may be owned by third parties. Such Intellectual Property Rights and Reproductions cannot and must not be made available for use without the prior written permission of the owner(s) of the relevant Intellectual Property Rights and/or Reproductions. 2 abstract This thesis examines the activity of the British musicians developing a practice of freely improvised music in the mid- to late-1960s, in conjunction with that of a group of British composers and performers contemporaneously exploring experimental possibilities within composed music; it investigates how these practices overlapped and interpenetrated for a period. -

Sprechen Über Neue Musik

Sprechen über Neue Musik Eine Analyse der Sekundärliteratur und Komponistenkommentare zu Pierre Boulez’ Le Marteau sans maître (1954), Karlheinz Stockhausens Gesang der Jünglinge (1956) und György Ligetis Atmosphères (1961) Dissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades der Philosophie (Dr. phil.) vorgelegt der Philosophischen Fakultät II der Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg, Institut für Musik, Abteilung Musikwissenschaft von Julia Heimerdinger ∗∗∗ Datum der Verteidigung 4. Juli 2013 Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Wolfgang Auhagen Prof. Dr. Wolfgang Hirschmann I Inhalt 1. Einleitung 1 2. Untersuchungsgegenstand und Methode 10 2.1. Textkorpora 10 2.2. Methode 12 2.2.1. Problemstellung und das Programm MAXQDA 12 2.2.2. Die Variablentabelle und die Liste der Codes 15 2.2.3. Auswertung: Analysefunktionen und Visual Tools 32 3. Pierre Boulez: Le Marteau sans maître (1954) 35 3.1. „Das Glück einer irrationalen Dimension“. Pierre Boulez’ Werkkommentare 35 3.2. Die Rätsel des Marteau sans maître 47 3.2.1. Die auffällige Sprache zu Le Marteau sans maître 58 3.2.2. Wahrnehmung und Interpretation 68 4. Karlheinz Stockhausen: Gesang der Jünglinge (elektronische Musik) (1955-1956) 85 4.1. Kontinuum. Stockhausens Werkkommentare 85 4.2. Kontinuum? Gesang der Jünglinge 95 4.2.1. Die auffällige Sprache zum Gesang der Jünglinge 101 4.2.2. Wahrnehmung und Interpretation 109 5. György Ligeti: Atmosphères (1961) 123 5.1. Von der musikalischen Vorstellung zum musikalischen Schein. Ligetis Werkkommentare 123 5.1.2. Ligetis auffällige Sprache 129 5.1.3. Wahrnehmung und Interpretation 134 5.2. Die große Vorstellung. Atmosphères 143 5.2.2. Die auffällige Sprache zu Atmosphères 155 5.2.3. -

Icebreaker: Apollo

Icebreaker: Apollo Start time: 7.30pm Running time: 2 hours 20 minutes with interval Please note all timings are approximate and subject to change Martin Aston looks into the history behind Apollo alongside other works being performed by eclectic ground -breaking composers. When man first stepped on the moon, on July 20th, 1969, ‘ambient music’ had not been invented. The genre got its name from Brian Eno after he’d released the album Discreet Music in 1975, alluding to a sound ‘actively listened to with attention or as easily ignored, depending on the choice of the listener,’ and which existed on the, ‘cusp between melody and texture.’ One small step, then, for the categorisation of music, and one giant leap for Eno’s profile, which he expanded over a series of albums (and production work) both song-based and ambient. In 1989, assisted by his younger brother Roger (on piano) and Canadian producer Daniel Lanois, Eno provided the soundtrack for Al Reinert’s documentary Apollo: the trio’s exquisitely drifting, beatific sound profoundly captured the mood of deep space, the suspension of gravity and the depth of tranquillity and awe that NASA’s astronauts experienced in the missions that led to Apollo 11’s Neil Armstrong taking that first step on the lunar surface. ‘One memorable image in the film was a bright white-blue moon, and as the rocket approached, it got much darker, and you realised the moon was above you,’ recalls Roger Eno. ‘That feeling of immensity was a gift: you just had to accentuate the majesty.’ In 2009, to celebrate the 40th anniversary of that epochal trip, Tim Boon, head of research at the Science Museum in London, conceived the idea of a live soundtrack of Apollo to accompany Reinert’s film (which had been re-released in 1989 in a re-edited form, and retitled For All Mankind. -

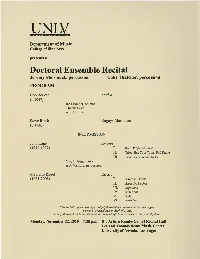

Doctoral Ensemble Recital Jeremy Meronuck, Percussion Luke Thatcher, Percussion PROGRAM

Department of Music College of Fine Arts presents a Doctoral Ensemble Recital Jeremy Meronuck, percussion Luke Thatcher, percussion PROGRAM Bob Becker Mudra (b.1947) Jack Steiner, soloist Charlie Gott A.J. Merlino Steve Reich Nagoya Marimbas (b.1936) INTERMISSION John Cage A mores (1912-1992) I. Solo: Prepared Piano II. Trio: ine Tom Toms, Pod Rattle ill. Trio: Seven Woodblocks Otto Ehling, piano A.J. Merlino, percussion Mauricio Kagel Rrrrrrr (1931-2008) I. Railroad Drama II. Ranz des Vaches III. Rigaudon IV. Rim Shot v. Ruff VI. Rutscher This recital is presented in partial fulfillment ofthe requirements for the degree Doctor ofMusical Arts in Applied Music. Jeremy Meronuck and Luke Thatcher are students ofDean Gronemeier and Timothy Jones. Monday, November 22,2010 7:30p.m. Dr. Arturo Rando-Grillot Recital Hall Lee and Thomas Beam Music Center University of Nevada, Las Vegas PROGRAM NOTES Mudra consists of music, which was originally composed to accompany the dance Mudra by choreographer Joan Phillips. Commissioned by INDE '90 and premiered in Toronto in March, 1990, as part of the DuMaurier Quay Works series, Mudra was awarded the National Art Centre Award for best collaboration between composer and choreographer. The music was subsequently edited and re-orchestrated as a concert piece for the percussion group NEXUS during May, 1990. Mudra is scored for marimba, vibraphone, songbells, glockenspiel, crotales, prepared drum and bass drum. Mudra was created, for the most part, using the "dance first" approach, in which the music is composed to fit pre-existing choreography. Thus, the rhythmic structure and overall form reflect the episodic and gestural character of the original choreography, which dealt with the conflict of traditional and modern issues in a multi-cultural urban society. -

Philip Glass

DEBARTOLO PERFORMING ARTS CENTER PRESENTING SERIES PRESENTS MUSIC BY PHILIP GLASS IN A PERFORMANCE OF AN EVENING OF CHAMBER MUSIC WITH PHILIP GLASS TIM FAIN AND THIRD COAST PERCUSSION MARCH 30, 2019 AT 7:30 P.M. LEIGHTON CONCERT HALL Made possible by the Teddy Ebersol Endowment for Excellence in the Performing Arts and the Gaye A. and Steven C. Francis Endowment for Excellence in Creativity. PROGRAM: (subject to change) PART I Etudes 1 & 2 (1994) Composed and Performed by Philip Glass π There were a number of special events and commissions that facilitated the composition of The Etudes by Philip Glass. The original set of six was composed for Dennis Russell Davies on the occasion of his 50th birthday in 1994. Chaconnes I & II from Partita for Solo Violin (2011) Composed by Philip Glass Performed by Tim Fain π I met Tim Fain during the tour of “The Book of Longing,” an evening based on the poetry of Leonard Cohen. In that work, all of the instrumentalists had solo parts. Shortly after that tour, Tim asked me to compose some solo violin music for him. I quickly agreed. Having been very impressed by his ability and interpretation of my work, I decided on a seven-movement piece. I thought of it as a Partita, the name inspired by the solo clavier and solo violin music of Bach. The music of that time included dance-like movements, often a chaconne, which represented the compositional practice. What inspired me about these pieces was that they allowed the composer to present a variety of music composed within an overall structure. -

Holmes Electronic and Experimental Music

C H A P T E R 2 Early Electronic Music in Europe I noticed without surprise by recording the noise of things that one could perceive beyond sounds, the daily metaphors that they suggest to us. —Pierre Schaeffer Before the Tape Recorder Musique Concrète in France L’Objet Sonore—The Sound Object Origins of Musique Concrète Listen: Early Electronic Music in Europe Elektronische Musik in Germany Stockhausen’s Early Work Other Early European Studios Innovation: Electronic Music Equipment of the Studio di Fonologia Musicale (Milan, c.1960) Summary Milestones: Early Electronic Music of Europe Plate 2.1 Pierre Schaeffer operating the Pupitre d’espace (1951), the four rings of which could be used during a live performance to control the spatial distribution of electronically produced sounds using two front channels: one channel in the rear, and one overhead. (1951 © Ina/Maurice Lecardent, Ina GRM Archives) 42 EARLY HISTORY – PREDECESSORS AND PIONEERS A convergence of new technologies and a general cultural backlash against Old World arts and values made conditions favorable for the rise of electronic music in the years following World War II. Musical ideas that met with punishing repression and indiffer- ence prior to the war became less odious to a new generation of listeners who embraced futuristic advances of the atomic age. Prior to World War II, electronic music was anchored down by a reliance on live performance. Only a few composers—Varèse and Cage among them—anticipated the importance of the recording medium to the growth of electronic music. This chapter traces a technological transition from the turntable to the magnetic tape recorder as well as the transformation of electronic music from a medium of live performance to that of recorded media. -

Third Coast Percussion

Third Coast Percussion Start time: 8pm Running time: 1 hour 45 minutes – including interval Please note all timings are approximate and subject to change Ruth Kilpatrick delves into tonight’s programme, and the ensemble’s passion for collaborative new composition. Chicago’s Third Coast Percussion is a Grammy Award winning ensemble, world renowned for their impressive arrangements of classic works, powerful new pieces and always inspiring performances. This concert sees them at the Barbican for the first time, with a programme celebrating the wealth of possibility that comes from open, honest collaboration. Featuring four UK premieres, the evening begins with Philip Glass’s Madeira River; re-named after the Amazon River and its tributaries by Brazilian group Uakti for their own custom-made instruments back in 1999. For their 2017 album Paddle To The Sea, Third Coast Percussion took inspiration from both the original piano works and the Uakti arrangement, to create their own six-minute piece. Perhaps their most well-known work to date, the classically trained quartet released an album of Steve Reich’s works in celebration of his 80th birthday in 2016, on Cedille Records, winning the Grammy for Best Chamber Music / Small Ensemble Performance. Reich’s influence on modern composition is vast; with Mallet Quartet offering a more melodic take on his perhaps more minimalist past. Scored for two marimbas and two vibraphones, the three movements over fifteen-minutes offer rhythmic energy and room for reflection all at once. The last piece of the first half is Perpetulum; composed for and in collaboration with Third Coast Percussion by Philip Glass. -

Supplement to the Music of Mauricio Kagel

Heile, Bjorn (2014) Supplement to the Music of Mauricio Kagel. Copyright © 2014 The Author Available under License Creative Commons Attribution Non-commercial No Derivatives. http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/96021/ Deposited on: 14 August 2014 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk Supplement To The Music of Mauricio Kagel (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2006) Björn Heile University of Glasgow Edition 1.0 Glasgow, August 2014 Table of Contents Illustrations ............................................................................................................................................ iii About this Publication ............................................................................................................................ iv Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................................. v Errata ...................................................................................................................................................... vi Early Work and Career ............................................................................................................................ 1 Dodecaphony ........................................................................................................................................ 34 The Late Work ...................................................................................................................................... -

Rethinking Minimalism: at the Intersection of Music Theory and Art Criticism

Rethinking Minimalism: At the Intersection of Music Theory and Art Criticism Peter Shelley A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2013 Reading Committee Jonathan Bernard, Chair Áine Heneghan Judy Tsou Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Music Theory ©Copyright 2013 Peter Shelley University of Washington Abstract Rethinking Minimalism: At the Intersection of Music Theory and Art Criticism Peter James Shelley Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Dr. Jonathan Bernard Music Theory By now most scholars are fairly sure of what minimalism is. Even if they may be reluctant to offer a precise theory, and even if they may distrust canon formation, members of the informed public have a clear idea of who the central canonical minimalist composers were or are. Sitting front and center are always four white male Americans: La Monte Young, Terry Riley, Steve Reich, and Philip Glass. This dissertation negotiates with this received wisdom, challenging the stylistic coherence among these composers implied by the term minimalism and scrutinizing the presumed neutrality of their music. This dissertation is based in the acceptance of the aesthetic similarities between minimalist sculpture and music. Michael Fried’s essay “Art and Objecthood,” which occupies a central role in the history of minimalist sculptural criticism, serves as the point of departure for three excursions into minimalist music. The first excursion deals with the question of time in minimalism, arguing that, contrary to received wisdom, minimalist music is not always well understood as static or, in Jonathan Kramer’s terminology, vertical. The second excursion addresses anthropomorphism in minimalist music, borrowing from Fried’s concept of (bodily) presence. -

Vendredi 10 Février Ensemble Intercontemporain Ensemble In

Roch-Olivier Maistre, Président du Conseil d’administration Laurent Bayle, Directeur général Vendredi 10 février Ensemble intercontemporain Dans le cadre du cycle Des pieds et des mains Du 10 au 12 février Vendredi 10 février 10 Vendredi | Vous avez la possibilité de consulter les notes de programme en ligne, 2 jours avant chaque concert, à l’adresse suivante : www.citedelamusique.fr Ensemble intercontemporain Ensemble intercontemporain Cycle Des pieds et des mains L’Ensemble intercontemporain présente deux concerts dans le cadre du cycle Des pieds et des mains à la Cité de la musique. Inori (un mot japonais qui signie « invocation, adoration ») est une expérience totale. La mimique quasi dansée des deux « solistes » emprunte le code de ses gestes de prière à diverses religions du monde. À chaque mouvement des mains correspond une note : Inori est en 1974 l’une des premières pièces de Stockhausen à se fonder sur une « formule », sorte d’hyper-mélodie qui non seulement est entendue comme telle mais se retrouve pour ainsi dire étirée à l’échelle de l’œuvre dans son entier, dont elle dicte et caractérise les diérentes parties. Enn, chacune des sections d’Inori se concentre sur un aspect du discours musical – dans l’ordre : rythme, dynamique, mélodie, harmonie et polyphonie –, si bien que la partition, selon le compositeur, « se développe comme une histoire de la musique » reparcourue en accéléré, depuis l’origine jusqu’à nos jours. Dans le saisissant Pas de cinq de Mauricio Kagel, composé en 1965, les cinq exécutants, munis d’une canne, parcourent et sillonnent une surface délimitée en forme de pentagone couvert de diérents matériaux.