Philip Glass

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

B&F Magazine Issue 31

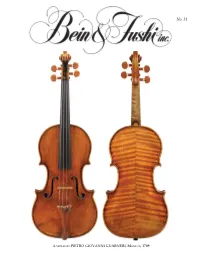

No. 31 A VIOLIN BY PIETRO GIOVANNI GUARNERI, MANTUA, 1709 superb instruments loaned to them by the Arrisons, gave spectacular performances and received standing ovations. Our profound thanks go to Karen and Clement Arrison for their dedication to preserving our classical music traditions and helping rising stars launch their careers over many years. Our feature is on page 11. Violinist William Hagen Wins Third Prize at the Queen Elisabeth International Dear Friends, Competition With a very productive summer coming to a close, I am Bravo to Bein & Fushi customer delighted to be able to tell you about a few of our recent and dear friend William Hagen for notable sales. The exquisite “Posselt, Philipp” Giuseppe being awarded third prize at the Guarneri del Gesù of 1732 is one of very few instruments Queen Elisabeth Competition in named after women: American virtuoso Ruth Posselt (1911- Belgium. He is the highest ranking 2007) and amateur violinist Renee Philipp of Rotterdam, American winner since 1980. who acquired the violin in 1918. And exceptional violins by Hagen was the second prize winner Camillo Camilli and Santo Serafin along with a marvelous of the Fritz Kreisler International viola bow by Dominique Peccatte are now in the very gifted Music Competition in 2014. He has hands of discerning artists. I am so proud of our sales staff’s Photo: Richard Busath attended the Colburn School where amazing ability to help musicians find their ideal match in an he studied with Robert Lipsett and Juilliardilli d wherehh he was instrument or bow. a student of Itzhak Perlman and Catherine Cho. -

2006 Fall Newsletter

THE ENVIROTECH NEWSLETTER Fall 2006 Volume 6, Number 2 Some Great Envirotech Films By Numerous Generous Envirotech Members Inside this issue: Editor’s Note: Last spring Jeffrey Stine made the good suggestion that it might be useful to begin compiling a list of films on envirotech subjects. The following list is the first install- ment in that project. Perhaps a dozen or so of you were kind enough of send in titles and Vegas Session Report 2 brief descriptions. My thanks to you all! But two Envirotechies—Lindy Biggs and Pat Mun- day—really outdid themselves by contributing long lists of films with richly detailed descrip- ET News 3 tions. Indeed, I did not have space to include all of Lindy’s good suggestions. But again following a suggestion from Jeffrey Stine, I propose to continue to compile and periodically Member news 4 publish further additions to this list in the future. So for those of you who perhaps did not have the time to send in your suggestions this go-around, keep the project in mind for the ASEH Sneak Preview 8 spring. Likewise, whenever you discover a new film of value, please take a few moments to send me an e-mail so I can include it in future editions of the newsletter and add it to the Position Available 9 master list. Note that for convenience and to maintain uniformity I have generally not included the names of individual contributors except where necessary to obtain the film. But I do Conferences & Calls 10 (Continued on page 13) Update on the Envirotech Book Project By Stephen Cutcliffe Important Dates: • December 1: Deadline Several years ago the Envirotech lected essays that would “challenge conven- for nominations for the special interest group began a very interest- tional thinking about the relationship be- Envirotech prize for ing list serve discussion on what constitutes tween technology and nature and about hu- best article—see page our human technological relationship with mankind’s relationship with both” in a way 5 the natural world. -

Cardiovascular and Other Outcomes Postintervention

CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE AND DIABETES Diabetes Care Volume 39, May 2016 709 Cardiovascular and Other ORIGIN Trial Investigators* Outcomes Postintervention With Insulin Glargine and Omega-3 Fatty Acids (ORIGINALE) Diabetes Care 2016;39:709–716 | DOI: 10.2337/dc15-1676 OBJECTIVE The Outcome Reduction With Initial Glargine Intervention (ORIGIN) trial reported neutral effects of insulin glargine on cardiovascular outcomes and cancers and reduced incident diabetes in high–cardiovascular risk adults with dysglycemia after 6.2 years of active treatment. Omega-3 fatty acids had neutral effects on cardiovascular outcomes. The ORIGIN and Legacy Effects (ORIGINALE) study mea- sured posttrial effects of these interventions during an additional 2.7 years. RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS Surviving ORIGIN participants attended up to two additional visits. The hazard of clinical outcomes during the entire follow-up period from randomization was calculated. RESULTS Of 12,537 participants randomized, posttrial data were analyzed for 4,718 originally allocated to insulin glargine (2,351) versus standard care (2,367), and 4,771 originally allocated to omega-3 fatty acid supplements (2,368) versus placebo (2,403). Posttrial, small differences in median HbA1c persisted (glargine 6.6% [49 mmol/mol], standard care 6.7% [50 mmol/mol], P = 0.025). From randomization to the end of posttrial follow-up, no differences were found between the glargine and standard care groups in myocardial infarction, stroke, or cardiovascular death (1,185 vs. 1,165 Corresponding author: Zubin Punthakee, zubin. events; hazard ratio 1.01 [95% CI 0.94–1.10]; P = 0.72); myocardial infarction, stroke, [email protected]. cardiovascular death, revascularization, or hospitalization for heart failure (1,958 vs. -

ED351261.Pdf

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 351 261 SO 022 575 AUTHOR Farnbach, Beth Earley, Ed. TITLE The Bill of Rights Alive! INSTITUTION Temple Univ., Philadelphia, PA. School of Law. SPONS AGENCY Commission on the Bicentennial of the United States Constitution, Washington, DC. PUB DATE 92 CONTRACT 91-CB-CX-0054 NOTE 100p.; Funding also received from the Pennsylvania Trial Lawyers Association. PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Use Teaching Guides (For Teacher) (052) EARS PRICE MF01/PC04 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Civil Liberties; Constitutional History; *Constitutional Law; Elementary Secondary Education; *Law Related Education; Learning Activities; Social Studies; Teaching Methods; United States History IDENTIFIERS *Bill of Rights; *United States Constitution ABSTRACT This collection of lesson plans presents ideas for educators and persons in the law and justice communityto teach young people about the Bill of Rights. The lesson plansare: "Mindwalk: An Introduction to the Law or How the Bill of Rights AffectsOur Liver"; "Bill of Rights Bingo"; "The Classroom 'ConstitutionalConvention': Writing A Constitution for Your Class"; "Rewriting the Billof Rights in Everyday Language"; "If James Madison Had Been inCharge of the World"; "Ranking Your Rights and Freedoms"; "Photojournalismand the Bill of Rights"; "Freedom Challenge"; "Do God andCountry Mix? The Free Exercise Clause and the Flag Salute"; "Religionand Secular Purpose"; "A Mock Supreme Court Hearing: Lyngv. Northwest Indian Cemettry Protective Association"; "Away with the Manger";"Choose on Choice: Pennsylvania's School Choice Legislationand the Separation of Church and State"; "An Impartial Jury: Voir Direand the Bill of Rights"; "Do You Really Need a Lawyer? The SixthAmendment & the Right to Counsel"; "From Brown to Bakke: The 14thAmendment"; "Drawing on Your Rights"; and "Bill of RightsMock Trial." Each lesson contains the lesson title, an overview, gradelevel, goals, a list of materials, possibleuses of outside resources, procedures/activities, and reflectionson the lesson. -

Sydney Film Festival Announces Essential Scorsese

MEDIA RELEASE THURSDAY 31 MARCH 2016 DAVID STRATTON CURATES SCORSESE RETROSPECTIVE Sydney Film Festival, Australian Centre for the Moving Image (ACMI) and the National Film and Sound Archive of Australia (NFSA) announce that David Stratton will present a program of 10 essential films directed by Martin Scorsese. The curated films will screen as the retrospective program during the 63rd Sydney Film Festival (8-19 June) and in Melbourne at ACMI (27 May-12 June) to coincide with ACMI’s exhibition SCORSESE (26 May-18 September). All 10 films will screen at the NFSA in Canberra (1-23 July) after Sydney Film Festival’s screenings. The retrospective program of ten titles, including specially imported 35mm prints, curated by David Stratton, entitled Essential Scorsese: Selected by David Stratton, features works by one of the most influential directors of our time, including Taxi Driver, Goodfellas, Raging Bull and The Age of Innocence. The renowned critic and broadcaster, was appointed director of the Sydney Film Festival 50 years ago, and held the position from 1966 to 1983. Stratton will introduce selected screenings in the retrospective program. David Stratton says: “Scorsese talks in a rapid-fire style as though he doesn’t have enough time to describe everything he knows. He’s like a character in a 1930s movie. His films are passionate too. His best are explosive in their impact, crammed with information and detail. On the one hand, his Catholic upbringing leads him to tackle religious subjects (The Last Temptation of Christ, Kundun) while the Saturday matinee kid in him revels in the trashy gore of his gangster films.” Essential Scorsese: Selected by David Stratton will screen over two weekends during the Festival (8 – 19 June) at the Art Gallery of NSW. -

Violinist Tim Fain and Google Introduce New Virtual Reality Video for Youtube

Dick Huey // Founder // [email protected] Peter Zimmerman // Head of Publicity // [email protected] Violinist Tim Fain and Google Introduce New Virtual Reality Video for YouTube NEW YORK, NY – NOVEMBER 5, 2015 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE To offer fans a more immersive experience, violinist Tim Fain today released a new virtual reality (VR) video for YouTube based on his original composition Resonance. In a close collaboration with Google, the VR video was filmed using Jump (g.co/Jump), which not only gives fans a vivid 360° experience, but also a realistic sense of depth so they can feel like they’re actually there. Turn in every direction to enjoy Fain’s mesmerizing performance. The VR video is best viewed with a Google Cardboard viewer using the YouTube app available for Android smartphones (iOS coming soon). You can also view the video in non-VR mode on desktop and iOS. Filmed by Jessica Brillhart, the Principal Filmmaker for VR at Google, and produced by Nick Kadner at Greencard Pictures, the video depicts Fain, who Vanity Fair magazine said “plays like a virtuoso and thinks like a cinematographer,” performing his own new work for solo violin and orchestra entitled Resonance with Eric Jacobsen (of The Knights) conducting a group of some of the finest musicians in New York City. Tim Fain commented “the potential of virtual reality for storytelling is so huge, and no one really knows where it's going to go, but I'm really excited to be right there at the forefront of what's unfolding. When director Jessica Brillhart first approached me about writing some music for RESONANCE, we talked about a song that could move very quickly from incredibly intimate (playing my violin softly for myself) all the way up to a full orchestra, and then back again in the space of a few minutes; it’s as if everything is happening in my imagination, evoking a feeling of the world unfolding in the moment as we are living it. -

Dissertation Revision

Harmonic Centricity in Philip Glass’ “The Grid” and “Cowboy Rock’n’Roll USA,” an original composition by Matthew Donald Aelmore B.M., Wichita State University, 2009 M.M., Manhattan School of Music, 2011 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music Composition and Theory University of Pittsburgh 2015 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences This dissertation was presented by Matthew Donald Aelmore It was defended on March 26, 2015 and approved by Marcia Landy, PhD, Professor of English/Film Studies Eric Moe, PhD, Professor of Music Composition and Theory Andrew Weintraub, PhD, Professor of Ethnomusicology Dissertation Advisor: Amy Williams, PhD, Professor of Music Composition and Theory ii Harmonic Centricity in Philip Glass’ “The Grid” and “Cowboy Rock’n’Roll USA,” an original composition Matthew Donald Aelmore, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2015 Copyright © by Matthew Donald Aelmore 2015 iii Harmonic Centricity in Philip Glass’ “The Grid” and “Cowboy Rock’n’Roll USA,” an original composition Matthew Aelmore, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2015 This dissertation analyzes the harmonic syntax of Philip Glass’ music for the scene “The Grid,” from the 1982 Godfrey Reggio film Koyaanisqatsi. Chapter 1 focuses on the five harmonic cycles, which are presented in twenty-one harmonic sections. Due to the effects of repetition, Glass’ harmonic cycles are satiated from the relationships of consonance and dissonance that characterize tonal harmony. The five harmonic cycles, which appear in twenty-one sections, are analyzed in terms of the type of harmonic centricity they assert: tonally harmonic centricity, contextually asserted harmonic centricity, and no harmonic centricity. -

Verbal Features of Film Reviews in the Modern American Media Discourse

Online Journal of Communication and Media Technologies, 2020, 10(3), e202020 e-ISSN: 1986-3497 Verbal Features of Film Reviews in the Modern American Media Discourse Marina R. Zheltukhina 1* 0000-0001-7680-4003 56669701900 A-7301-2015 Gennady G. Slyshkin 2 0000-0001-8121-0250 57191286505 G-1470-2014 Galina N. Gumovskaya 3 0000-0002-5823-792X Ekaterina A. Baranova 4 0000-0003-1794-9936 57211620013 AAF-3744-2019 Natalia G. Sklyarova 5 0000-0002-2875-3317 57193058610 K-3848-2017 Ksenya S. Vorkina 6 0000-0002-3804-3925 Lyudmila A. Donskova 7 0000-0002-7432-3908 1 Institute of Foreign Languages, Volgograd State Socio-Pedagogical University, Volgograd, RUSSIA 2 Institute of Linguistics and Intercultural Communication, I.M. Sechenov First Moscow State Medical University (Sechenov University), Institute of Law and National Security, Russian Presidential Academy of National Economy and Public Administration, Moscow, RUSSIA 3 Foreign Languages Department, National Research University Higher School of Economics, Moscow, RUSSIA 4 Communicative Management Department, Journalism Chair, Russian State Social University, Moscow, RUSSIA 5 Institute of philology, journalism and cross-cultural communication, Southern Federal University, Rostov-on-Don, RUSSIA 6 Faculty of Philology, Peoples’ Friendship University of Russia (RUDN University), Moscow, RUSSIA 7 Department of Foreign Languages, Kuban State Agrarian University, Krasnodar, RUSSIA * Corresponding author: [email protected] Citation: Zheltukhina, M. R., Slyshkin, G. G., Gumovskaya, G. N., Baranova, E. A., Sklyarova, N. G., Vorkina, K. S., & Donskova, L. A. (2020). Verbal Features of Film Reviews in the Modern American Media Discourse. Online Journal of Communication and Media Technologies, 10(3), e202020. https://doi.org/10.30935/ojcmt/8386 ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Received: 18 Feb 2020 The article discusses the verbal specifics of film reviews. -

Orientalist Commercializations: Tibetan Buddhism in American Popular Film

Journal of Religion & Film Volume 2 Issue 2 October 1998 Article 5 October 1998 Orientalist Commercializations: Tibetan Buddhism in American Popular Film Eve Mullen Mississippi State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf Recommended Citation Mullen, Eve (1998) "Orientalist Commercializations: Tibetan Buddhism in American Popular Film," Journal of Religion & Film: Vol. 2 : Iss. 2 , Article 5. Available at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf/vol2/iss2/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Religion & Film by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Orientalist Commercializations: Tibetan Buddhism in American Popular Film Abstract Many contemporary American popular films are presenting us with particular views of Tibetan Buddhism and culture. Unfortunately, the views these movies present are often misleading. In this essay I will identify four false characterizations of Tibetan Buddhism, as described by Tibetologist Donald Lopez, characterizations that have been refuted by post-colonial scholarship. I will then show how these misleading characterizations make their way into three contemporary films, Seven Years in Tibet, Kundun and Little Buddha. Finally, I will offer an explanation for the American fascination with Tibet as Tibetan culture is represented in these films. This article is available in Journal of Religion & Film: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf/vol2/iss2/5 Mullen: Orientalist Commercializations Tibetan religion and culture are experiencing an unparalleled popularity. Tibetan Buddhism and Tibetan history are commonly the subjects of Hollywood films. -

A More Attractive ‘Way of Getting Things Done’ Freedom, Collaboration and Compositional Paradox in British Improvised and Experimental Music 1965-75

A more attractive ‘way of getting things done’ freedom, collaboration and compositional paradox in British improvised and experimental music 1965-75 Simon H. Fell A thesis submitted to the University of Huddersfield in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Huddersfield September 2017 copyright statement i. The author of this thesis (including any appendices and/or schedules to this thesis) owns any copyright in it (the “Copyright”) and he has given The University of Huddersfield the right to use such Copyright for any administrative, promotional, educational and/or teaching purposes. ii. Copies of this thesis, either in full or in extracts, may be made only in accordance with the regulations of the University Library. Details of these regulations may be obtained from the Librarian. This page must form part of any such copies made. iii. The ownership of any patents, designs, trade marks and any and all other intellectual property rights except for the Copyright (the “Intellectual Property Rights”) and any reproductions of copyright works, for example graphs and tables (“Reproductions”), which may be described in this thesis, may not be owned by the author and may be owned by third parties. Such Intellectual Property Rights and Reproductions cannot and must not be made available for use without the prior written permission of the owner(s) of the relevant Intellectual Property Rights and/or Reproductions. 2 abstract This thesis examines the activity of the British musicians developing a practice of freely improvised music in the mid- to late-1960s, in conjunction with that of a group of British composers and performers contemporaneously exploring experimental possibilities within composed music; it investigates how these practices overlapped and interpenetrated for a period. -

Advance Program Notes Powaqqatsi: Life in Transformation Philip Glass Ensemble Friday, November 1, 2013, 8 PM

Advance Program Notes Powaqqatsi: Life in Transformation Philip Glass Ensemble Friday, November 1, 2013, 8 PM These Advance Program Notes are provided online for our patrons who like to read about performances ahead of time. Printed programs will be provided to patrons at the performances. Programs are subject to change. CENTER FOR THE ARTS AT VIRGINIA TECH presents POWAQQATSI LIFE IN TRANSFORMATION The CANNON GROUP INC. A FRANCIS FORD COPPOLA and GEORGE LUCAS Presentation Music by Directed by PHILIP GLASS GODFREY REGGIO Photography by Edited by GRAHAM BERRY IRIS CAHN/ ALTON WALPOLE LEONIDAS ZOURDOUMIS Performed by PHILIP GLASS and the PHILIP GLASS ENSEMBLE conducted by Michael Riesman with the Blacksburg Children’s Chorale Patrice Yearwood, artistic director PHILIP GLASS ENSEMBLE Philip Glass, Lisa Bielawa, Dan Dryden, Stephen Erb, Jon Gibson, Michael Riesman, Mick Rossi, Andrew Sterman, David Crowell Guest Musicians: Ted Baker, Frank Cassara, Nelson Padgett, Yousif Sheronick The call to prayer in tonight’s performance is given by Dr. Khaled Gad Music Director MICHAEL RIESMAN Sound Design by Kurt Munkacsi Film Executive Producers MENAHEM GOLAN and YORAM GLOBUS Film Produced by MEL LAWRENCE, GODFREY REGGIO and LAWRENCE TAUB Production Management POMEGRANATE ARTS Linda Brumbach, Producer POWAQQATSI runs approximately 102 minutes and will be performed without intermission. SUBJECT TO CHANGE PO-WAQ-QA-TSI (from the Hopi language, powaq sorcerer + qatsi life) n. an entity, a way of life, that consumes the life forces of other beings in order to further its own life. POWAQQATSI is the second part of the Godfrey Reggio/Philip Glass QATSI TRILOGY. With a more global view than KOYAANISQATSI, Reggio and Glass’ first collaboration, POWAQQATSI, examines life on our planet, focusing on the negative transformation of land-based, human- scale societies into technologically driven, urban clones. -

The Philip Glass Ensemble in Downtown New York, 1966-1976 David Allen Chapman Washington University in St

Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs) Spring 4-27-2013 Collaboration, Presence, and Community: The Philip Glass Ensemble in Downtown New York, 1966-1976 David Allen Chapman Washington University in St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/etd Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Chapman, David Allen, "Collaboration, Presence, and Community: The hiP lip Glass Ensemble in Downtown New York, 1966-1976" (2013). All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs). 1098. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/etd/1098 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs) by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY IN ST. LOUIS Department of Music Dissertation Examination Committee: Peter Schmelz, Chair Patrick Burke Pannill Camp Mary-Jean Cowell Craig Monson Paul Steinbeck Collaboration, Presence, and Community: The Philip Glass Ensemble in Downtown New York, 1966–1976 by David Allen Chapman, Jr. A dissertation presented to the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2013 St. Louis, Missouri © Copyright 2013 by David Allen Chapman, Jr. All rights reserved. CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES ....................................................................................................................