Rethinking Minimalism: at the Intersection of Music Theory and Art Criticism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In the Player Piano Conventional Piano

;- THE AMICA NEWS BULLETIN OF THE AUTOMATIC MUSICAL INSTRUMENT COLLECTORS' ASSOCIATION NOVEMBER 1978 VOLUME 15 NUMBER 9 INTERNATlONAL OFFICERS CHAPTER OFFICERS PRESIDENT Bob Rosencrans 36 Hampden Rd. NO. CALIFORNIA Upper Darby, PA 19082 Pres.: Howard Koff Vice Pres: Phil McCoy VICE PRESIDENT Sec. David Fryman Bill Eicher Treas.: Bob Wilcox 465 Winding Way Reporter: Stuart Hunter Dayton, OH 45429 SO. CALIFORNIA Pres.: Francis Cherney SECRETARY Vice Pres.: Mary Lilien Jim Weisenborne Sec.: Greg Behnke AMICA MEMBERSHIP RATES: 73 Nevada St. Treas.: Roy Shelso Rochester, MI 48063 Reporter: Bill Toeppe Continuing Members: $1 S Dues TEXAS New Members, add $S processing fee PUBLISHER Pres.: Haden Vandiver Tom Beckett Vice Pres.: Bill Flynt Lapsed Members, add $3 processing fee 681 7 CI iffbrook SeclTreas.: Charlie Johnson Dallas, TX 75240 Reporter: Dick Barnes MIDWEST MEMBERSHIP SECRETARY Pres.: Bennet Leedy (New memberships and Vice Pres .. Jim Prendergast mailing problems) Sec.: Jim Weisenborne THE AMICA NEWS BULLETIN Charlie W Johnson Treas.: Alvin Wulfekuhl PO. Box 38623 Reporter: Molly Yeckley Dallas, Texas 75238 PHILADELPHIA AREA TREASURER Pres.: Mike Naddeo Published by the Automatic Musical Instrument Collectors' Jack & Mary Riffle Vice Pres. John Berry Association, a non-profit club devoted to the restoration, distribu 5050 Eastside Calpella Rd. Sec. Dick Price tion and enjoyment of musical instruments using perforated paper Ukiah, CA 95482 Treas: Claire Lambert music rolls. Reporter: Allen Ford Contributions: All subjects of interest to readers of the bulletin BOARD REPRESENTATIVES SOWNY (So. Ontario, West NY) are encouraged and invited by the publisher. All articles must be N. Cal. Frank Loob Pres.: Chuck Hannen received by the 10th of the preceding month. -

The Present Position of Authenticity

Performance Practice Review Volume 2 Article 2 Number 2 Fall The rP esent Position of Authenticity Robert Donington Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr Part of the Music Practice Commons Donington, Robert (1989) "The rP esent Position of Authenticity," Performance Practice Review: Vol. 2: No. 2, Article 2. DOI: 10.5642/ perfpr.198902.02.2 Available at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr/vol2/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Claremont at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Performance Practice Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. On Behalf of Historical Performance The Present Position of Authenticity Robert Donington Not for the first time, the great divide is opening up between those of us, such as the readers of this Review, who aspire to authenticity in performing early music, and those others who argue, on the contrary, that authenticity is either unattainable or undesirable or both. It is also possible to take up a middle position, allowing for a measure of compromise adjusted to the practical circumstances of a given situation. But even so, it is the basic orientation of the performer which really counts. The effect of it is by no means merely theoretical. The differences in performing practice at the present time are startling, and their significance for every variety of our musical experience is growing all the time. It is not only for early music that the issue is getting to be so very topical. -

City Research Online

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Pace, I. (2017). Michael Finnissy - The Piano Music (10 and 11) - Brochure from Conference 'Bright Futures, Dark Pasts'. This is the other version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/17523/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] BRIGHT FUTURES, DARK PASTS Michael Finnissy at 70 Conference at City, University of London January 19th-20th 2017 Bright Futures, Dark Pasts Michael Finnissy at 70 After over twenty-five years sustained engagement with the music of Michael Finnissy, it is my great pleasure finally to be able to convene a conference on his work. This event should help to stimulate active dialogue between composers, performers and musicologists with an interest in Finnissy’s work, all from distinct perspectives. It is almost twenty years since the publication of Uncommon Ground: The Music of Michael Finnissy (Aldershot: Ashgate, 1998). -

Minimal Music And

SE Volker Straebel: Minimal Music and Art | TU Berlin – Fachgebiet Audiokommunikation WiSe 2012/13 | 3135 L 350 | E-N 324 | Donnerstag 12-14 | [email protected] Ausgehend von den klassischen Positionen der Minimal Music der 1960er und 70er Jahr (Philip Glass, Steve Reich, Terry Riley, La Monte Young) sollen zunächst charakteristische Kompositionsverfahren analysiert werden. Deren Wirkung wird sowohl wahrnehmungspsychologisch wie rezeptionsästhetisch betrachtet. Die vergleichende Lektüre von Schlüsseltexten zur Minimal Art soll schließlich zur Diskussion der Interdependenz der beiden Kunstformen führen. 18.10. Einführung 25.10. Wiederholungen, Pattern, Serien Andreas Stahl: "Kriterien der Wiederholung: Zum Umgang mit einem Phänomen", in: Dissonanz , Nr. 84 (Dez. 2003), S. 10-17 [UdK Bibliothek] Sol LeWitt . New York: The Museum of Modern Art 1978, S. 56-85 [SeAp] 01.11. Steve Reichs Tape Music Steve Reich: It's Gonna Rain [Audio] Steve Reich: Come Out [Audio] Keith Potter: Four Musical Minimalists: La Monte Young, Terry Riley, Steve Reich, Philip Glass . Cambridge - New York: Cambridge University Press 2000, S. 160-170, 176-180 [SeAp] 08.11. Steve Reich: Music as a gradual process Steve Reich: Piano Phase [Audio/SeAp] Steve Reich: Four Organs [Audio/SeAp] Steve Reich: Writings on Music, 1965-2000 , hrsg. v. Paul Hiller. New York: Oxford University Press 2000, S. 22- 36, 38-50 [SeAp] 15.11. Steve Reich: Drumming und Music for 18 Musicians Steve Reich: Drumming [Audio/SeAp] Steve Reich: Music for 18 Musicians [Audio/SeAp] Steve Reich: Writings on Music, 1965-2000 , hrsg. v. Paul Hiller. New York: Oxford University Press 2000, S. 63- 67, 87-90 [SeAp] 22.11. -

Discovering the Contemporary

of formalist distance upon which modernists had relied for understanding the world. Critics increasingly pointed to a correspondence between the formal properties of 1960s art and the nature of the radically changing world that sur- rounded them. In fact formalism, the commitment to prior- itizing formal qualities of a work of art over its content, was being transformed in these years into a means of discovering content. Leo Steinberg described Rauschenberg’s work as “flat- bed painting,” one of the lasting critical metaphors invented 1 in response to the art of the immediate post-World War II Discovering the Contemporary period.5 The collisions across the surface of Rosenquist’s painting and the collection of materials on Rauschenberg’s surfaces were being viewed as models for a new form of realism, one that captured the relationships between people and things in the world outside the studio. The lesson that formal analysis could lead back into, rather than away from, content, often with very specific social significance, would be central to the creation and reception of late-twentieth- century art. 1.2 Roy Lichtenstein, Golf Ball, 1962. Oil on canvas, 32 32" (81.3 1.1 James Rosenquist, F-111, 1964–65. Oil on canvas with aluminum, 10 86' (3.04 26.21 m). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. 81.3 cm). Courtesy The Estate of Roy Lichtenstein. New Movements and New Metaphors Purchase Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Alex L. Hillman and Lillie P. Bliss Bequest (both by exchange). Acc. n.: 473.1996.a-w. Artists all over the world shared U.S. -

A Heretic in the Schoenberg Circle: Roberto Gerhard's First Engagement with Twelve-Tone Procedures in Andantino

Twentieth-Century Music 16/3, 557–588 © Cambridge University Press 2019. This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. doi: 10.1017/S1478572219000306 A Heretic in the Schoenberg Circle: Roberto Gerhard’s First Engagement with Twelve-Tone Procedures in Andantino DIEGO ALONSO TOMÁS Abstract Shortly before finishing his studies with Arnold Schoenberg, Roberto Gerhard composed Andantino,a short piece in which he used for the first time a compositional technique for the systematic circu- lation of all pitch classes in both the melodic and the harmonic dimensions of the music. He mod- elled this technique on the tri-tetrachordal procedure in Schoenberg’s Prelude from the Suite for Piano, Op. 25 but, unlike his teacher, Gerhard treated the tetrachords as internally unordered pitch-class collections. This decision was possibly encouraged by his exposure from the mid- 1920s onwards to Josef Matthias Hauer’s writings on ‘trope theory’. Although rarely discussed by scholars, Andantino occupies a special place in Gerhard’s creative output for being his first attempt at ‘twelve-tone composition’ and foreshadowing the permutation techniques that would become a distinctive feature of his later serial compositions. This article analyses Andantino within the context of the early history of twelve-tone music and theory. How well I do remember our Berlin days, what a couple we made, you and I; you (at that time) the anti-Schoenberguian [sic], or the very reluctant Schoenberguian, and I, the non-conformist, or the Schoenberguian malgré moi. -

Microsoft Outlook

Dave M. Peck From: Squidco <[email protected]> Sent: Thursday, September 14, 2017 10:11 AM To: Dave M. Peck Subject: SQUIDCO Email Update September 14, 2017 UPDATE September 14, 2017 We wanted to make a new art— new expressions of art— in an art world that was, for us, traditional." —Herman Nitsch Essential Labels Alga Marghen KARLRECORDS Art Yard Matchless Clang Mikroton Recordings Confront Room40 Creative Sources Someone Good / Room40 Discus Taping Policies Evil Clown Trost Records Fragment Factory Wide Hive Holidays Records Creative Artists 1 • Abecassis, Eryck / Francisco Meirino • Derek Bailey / Mick Beck / Paul Hession • Borbetomagus • Tony Buck • Deep Tide Quartet (Archer / Macari / Cole / Shaw) • The Elks (Fagaschinski/Allbee/Roisz/Zapparoli) • Georg Graewe / Mark Sanders • Haco • Junk & The Beast (Petr Vrba / Veronika Mayer) • Alice Kemp • Leap of Faith • Kurt Liedwart • Roscoe Mitchell • Dafna Naphtali / Gordon Beeferman • Hermann Nitsch • Orfeo 5 (Blezard/Bourne/Jafrate w/ Prince/Oliver/Kane) • Charlemagne Palestine • Pat Patrick And The Baritone Saxophone Retinue • Massimo Pupillo / Alexandre Babel / Caspar Brotzmann • Ernesto Rodrigues / Ulrike Brand / Olaf Rupp • Sakata / Mota / Di Domenico / Calleja • Udo Schindler • String Theory [Boston, USA] • String Theory [PORTUGAL] • Eckard Vossas 4 (Vossas / Fields / Henkel / Nabatov) • Christian Wolfarth / Jason Kahn • Christian Wolff / Eddie Prevost • Nate Wooley / Daniele Martini / Joao Lobo • Zeitkratzer / Svetlana Spajic/Dragana Tomic/Obrad Milic • Zeitkratzer + Elliott Sharp Jazz & Improvisation Bailey, Derek / Mick Beck / Paul Hession: Meanwhile, Back In Sheffield... (Discus) Free improvising guitar legend Derek Bailey was invited to perform in his home town of Sheffield, England in 2004 with the trio of Mick Beck on tenor sax, bassoon, and whistles, and Paul Hession on drums, Bailey's first visit in many years, and a joyful occasion as the collective group explores a wide range of approaches to creating instant compositions. -

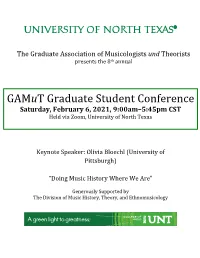

8Th Annual Gamut Conference Program

The Graduate Association of Musicologists und Theorists presents the 8th annual GAMuT Graduate Student Conference Saturday, February 6, 2021, 9:00am–5:45pm CST Held via Zoom, University of North Texas Keynote Speaker: Olivia Bloechl (University of Pittsburgh) “Doing Music History Where We Are” Generously Supported by The Division of Music History, Theory, and Ethnomusicology Program 9:00 Welcome and Opening remarks Peter Kohanski, GAMuT President/Conference Co-Chair Benjamin Brand, PhD, Professor of Music History and Chair of the Division of Music History, Theory, and Ethnomusicology 9:15 Race and Culture in the Contemporary Music Scene Session Chair: Rachel Schuck “Sounds of the 'Hyperghetto': Sounded Counternarratives in Newark, New Jersey Club Music Production and Performance” Jasmine A. Henry (Rutgers University) “‘I Opened the Lock in My Mind’: Centering the Development of Aeham Ahmad’s Oriental Jazz Style from Syria to Germany” Katelin Webster (Ohio State University) “Keeping the Tradition Alive: The Virtual Irish Session in the time of COVID-19” Andrew Bobker (Michigan State University) 10:45 Break 11:00 Reconsidering 20th-Century Styles and Aesthetics Session Chair: Rachel Gain “Diatonic Chromaticism?: Juxtaposition and Superimposition as Process in Penderecki's Song of the Cherubim” Jesse Kiser (University of Buffalo) “Adjusting the Sound, Closing the Mind: Foucault's Episteme and the Cultural Isolation of Contemporary Music” Paul David Flood (University of California, Irvine) 12:00 Lunch, on your own 1:00 Keynote Address Session -

Lucie Vítková (1985, Boskovice, CZ); +1 347 967 2997; [email protected];

Lucie Vítková (1985, Boskovice, CZ); +1 347 967 2997; [email protected]; http://www.vitkovalucie.com. I am a composer, performer and improviser of accordion, harmonica, voice and dance from the Czech Republic. My work pursues two lines of enquiry: my compositional practice focuses on sonification (compositions based on abstract models derived from physical objects), while my improvisational practice explores characteristics of discrete spaces through the interaction between sound and movement. Recently, I have become particularly interested in the question of social relationships in music and their implications for the structural organization of musical pieces. I explore this theme in all aspects of my work. Education: [2013-present] Janacek Academy of Music and Performing Arts Brno (JAMU Brno), CZ: Doctorate in composition and music theory (Ph.D.) with Peter Graham; in the academic year 2014/2015 recipient of Nadace Český hudební fond scholarship. [1/2016-1/2017] Columbia University NYC, USA: Visiting scholar with Prof. George E. Lewis. [2/2015-12/2015] Universität der Künste Berlin, DE: Recipient of Erasmus Scholarship for studies in composition and music theory with Marc Sabat. [9/2014-1/2015] Universität der Künste Berlin: Recipient of DAAD scholarship (Deutscher Akademischer Austausch Dienst). [2011-13] JAMU Brno: Master’s Degree (MgA.) in composition with Martin Smolka and Peter Graham, including the following international exchanges: [2011-12] Royal Conservatoire The Hague, NL: Recipient of Erasmus Scholarship for studies in composition with Martijn Padding, Cornelis de Bondt, Gilius van Bergeijk and Yannis Kyriakides, and in sonology (a subset of sound studies) with Paul Berg, Joel Ryan, Peter Pabon, Richard Barrett and Kees Tazelaar. -

David Quigley Learning to Live: Preliminary Notes for a Program Of

David Quigley In an essay published in 2009, Boris could play in a broader social context influenced the founding director John Groys makes the claim that “today art beyond the narrow realm of the art Andrew Rice, as well as the professors Learning to Live: education has no definite goal, no world. Josef Albers, Merce Cunningham, Robert Preliminary Notes method, no particular content that can Motherwell, John Cage, and the poets be taught, no tradition that can be Performing Pragmatism: Robert Creeley and Charles Olson. for a Program of Art transmitted to a new generation—which Art as Experience Unlike other trajectories of the critique Education for the is to say, it has too many.”69 While one On the first pages of Dewey’s Art as of the art object, the Deweyian tradition might agree with this diagnosis, one Experience from 1934, we read: did not deny the special status of art in 21st Century. immediately wonders how we should itself but rather resituated it within a Après John Dewey assess it. Are we to merely tacitly “By one of the ironic perversities that continuum of human experience. Dewey, acknowledge this situation or does this often attend the course of affairs, the as a thinker of egalitarianism and critique imply a call for change? Is this existence of the works of art upon which democracy, created a theory of art lack (or paradoxical overabundance) of the formation of an aesthetic theory based on the fundamental continuity goals, methods or content inherent to depends has become an obstruction of experience and practice, making the very essence of art education, or is to theory about them. -

Alchemy of Seeing Much Spoken About Following Her Graduate Exhibition, Sean O’Toole Catches up with Young Cape Town Artist Daniella Mooney to Ask About an Oil Spill

BYT/02/2010 DANIELLA MOONEY Alchemy of seeing Much spoken about following her graduate exhibition, Sean O’Toole catches up with young Cape Town artist Daniella Mooney to ask about an oil spill TOP LEFT Daniella Mooney, Your Sky, 2009, mixed media, used engine oil, 244 x 244 x 25cm TOP RIGHT Warning note installed after ‘accident’ in studio BOTTOM Daniella Mooney, If the Doors of Perception were cleansed, 2009, Mahogany Sapele, airbrushed perspex, 35.5 x 35.5cm BYT/02/2010 The context: a graduate exhibition at the Michaelis School She mentions the Danish artist Olafur Eliasson, also James Turrell. Obvious of Fine Art. The time: early afternoon, December 2009. The venue: an references, once you think about it, unobvious when you consider how their artist’s studio on a first floor. The text on the wall explains that the sculptural ideas are engaged locally. Since we’re charting influences, I ask about her ex- objects on display belong to Daniella Mooney. One work in particular partner, the young Cape Town sculptor Rowan Smith: “I admire his skill. dominates the space. Entitled Your Sky, it is not easily described. Here It was great because we both love working with wood. He really opened my goes. Suspended in space by cable rigging, a square-shaped object hovers eyes to wood carving and assembling.” over two wooden ladders. The ladders are an invitation to poke your head Previously an assistant to Paul Edmunds and hard at work helping Julia through the bottom of the floating object. Naturally you do. It’s then that Rose Clark when we meet, I ask about the title to her graduate show. -

Experimental

Experimental Discussão de alguns exemplos Earle Brown ● Earle Brown (December 26, 1926 – July 2, 2002) was an American composer who established his own formal and notational systems. Brown was the creator of open form,[1] a style of musical construction that has influenced many composers since—notably the downtown New York scene of the 1980s (see John Zorn) and generations of younger composers. ● ● Among his most famous works are December 1952, an entirely graphic score, and the open form pieces Available Forms I & II, Centering, and Cross Sections and Color Fields. He was awarded a Foundation for Contemporary Arts John Cage Award (1998). Terry Riley ● Terrence Mitchell "Terry" Riley (born June 24, 1935) is an American composer and performing musician associated with the minimalist school of Western classical music, of which he was a pioneer. His work is deeply influenced by both jazz and Indian classical music, and has utilized innovative tape music techniques and delay systems. He is best known for works such as his 1964 composition In C and 1969 album A Rainbow in Curved Air, both considered landmarks of minimalist music. La Monte Young ● La Monte Thornton Young (born October 14, 1935) is an American avant-garde composer, musician, and artist generally recognized as the first minimalist composer.[1][2][3] His works are cited as prominent examples of post-war experimental and contemporary music, and were tied to New York's downtown music and Fluxus art scenes.[4] Young is perhaps best known for his pioneering work in Western drone music (originally referred to as "dream music"), prominently explored in the 1960s with the experimental music collective the Theatre of Eternal Music.