The Archival Record of German-Language Groups in Canada: a Survey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

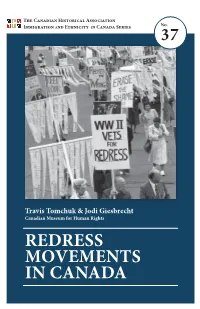

Redress Movements in Canada

Editor: Marlene Epp, Conrad Grebel University College University of Waterloo Series Advisory Committee: Laura Madokoro, McGill University Jordan Stanger-Ross, University of Victoria Sylvie Taschereau, Université du Québec à Trois-Rivières Copyright © the Canadian Historical Association Ottawa, 2018 Published by the Canadian Historical Association with the support of the Department of Canadian Heritage, Government of Canada ISSN: 2292-7441 (print) ISSN: 2292-745X (online) ISBN: 978-0-88798-296-5 Travis Tomchuk is the Curator of Canadian Human Rights History at the Canadian Museum for Human Rights, and holds a PhD from Queen’s University. Jodi Giesbrecht is the Manager of Research & Curation at the Canadian Museum for Human Rights, and holds a PhD from the University of Toronto. Cover image: Japanese Canadian redress rally at Parliament Hill, 1988. Photographer: Gordon King. Credit: Nikkei National Museum 2010.32.124. REDRESS MOVEMENTS IN CANADA Travis Tomchuk & Jodi Giesbrecht Canadian Museum for Human Rights All rights reserved. No part of this publication maybe reproduced, in any form or by any electronic ormechanical means including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the Canadian Historical Association. Ottawa, 2018 The Canadian Historical Association Immigration And Ethnicity In Canada Series Booklet No. 37 Introduction he past few decades have witnessed a substantial outpouring of Tapologies, statements of regret and recognition, commemorative gestures, compensation, and related measures -

The Impact of Anti-German Hysteria in New Ulm, Minnesota and Kitchener, Ontario: a Comparative Study Christopher James Wright Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Graduate Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2011 The impact of anti-German hysteria in New Ulm, Minnesota and Kitchener, Ontario: a comparative study Christopher James Wright Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Wright, Christopher James, "The impact of anti-German hysteria in New Ulm, Minnesota and Kitchener, Ontario: a comparative study" (2011). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 12043. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd/12043 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The impact of anti-German hysteria and the First World War in New Ulm, Minnesota and Kitchener, Ontario: a comparative study By Christopher James Wright A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ART Major: History Program of Study Committee: Kathleen Hilliard, Major Professor Charles Dobbs Michael Dahlstrom Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2011 Copyright © Christopher James Wright, 2011. All rights reserved . ii TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 2. 14 MILES EAST TO BERLIN 13 CHAPTER 3. ARE YOU IN FAVOR OF CHANGING THE NAME 39 OF THIS CITY? NO!! CHAPTER 4. COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS AND CONCLUSION 66 APPENDIX 81 REFERENCES CITED 85 1 CHAPTER ONE INTRODUCTION New Ulm, Minnesota is home to one of the most ethnically German communities outside of Germany. -

German Culture. INSTITUTION Manitoba Univ., Winnipeg

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 282 074 CE 047 326 AUTHOR Harvey, Dexter; Cap, Orest TITLE Elderly Service Workers' Training Project. Block B: Cultural Gerontology. Module B.2: German Culture. INSTITUTION Manitoba Univ., Winnipeg. Faculty of Education. SPONS AGENCY Department of National Health and Welfare, Ottawa (Ontario). PUB DATE 87 GRANT 6553-2-45 NOTE 42p.; For related documents, see ED 273 809=819 and CE 047 321-333. AVAILABLE FROMFaculty of Education, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada R3T 2N2. PUB TYPE Guides - Classroom use Materials (For Learner) (051) EDRS PRICE MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Aging (Individuals); Client Characteristics (Human Services); *Counselor Training; *Cross Cultural Training; *Cultural Background; *Cultural Context; Cultural Education; Ethnic Groups; Foreign Countries; German; Gerontology; Human Services; Immigrants; Interpersonal Competence; Learning Modules; Older Adults; Postsecondary Education IDENTIFIERS *German Canadians; *Manitoba ABSTRACT This learning module, which is part of a three-block Series intended to help human service workers develop the skills necessary to solve the problems encountered in their daily contact With elderly clients of different cultural backgrounds, deals with German culture. The first section provides background information about the German migrations to Canada and the German heritage. The module's general objectives are described next. The remaining Sections deal with German settlements in Manitoba, the bond between those who are able to understand and speak the German language, the role of religion and its importance in the lives of German-speaking Canadians, the value of family ties to German-speaking Canadians, customs common to German Canadians, and the relationship between the German-Canadian family and the neighborhood/community. -

1.4.3 We Are All Canadians, No Matter Which Origin Immediately After the Beginning of the War in September 1914 Some German-Cana

1.4.3 We are all Canadians, no matter which origin Immediately after the beginning of the War in September 1914 some German-Canadians felt that Canada should not be involved in Britain’s war and that German-Canadians’ taxes should not go to the war effort. Count Alfred von Hammerstein, who had founded the Alberta Herold and then made his name in the early 1900s exploring Alberta’s North for oil in what would be called the oil sands, came onto the political scene in February 1915 with the Canada First Movement, an attempt to remove all foreign influences from politics which might endanger the good relationships among the various ethnic groups in Canada, among them Canadians of German, Austrian, French, English or American nationality, and to stay out of the War.1 The principles of the Canada First Movement included: equality of all citizens, no matter whether they were of British origin or not; election of representatives who represented the Germans’ traditional ideals of honesty, integrity and hard work in government; employment of naturalized citizens in high and low positions in government. Canada should not be forgotten over the war in Europe; the government should create work; Canada should be able, after the war’s end, to make its own decisions on peace or war. The Movement promoted a single Canadian identity: there should no longer be French-Canadians, English-Canadians, German-Canadians or foreigners, but only “Canadian citizens.”2 Von Hammerstein said that he was willing to run for office in the next Dominion election to lend a voice to the Germans in the House of Commons if his offer found a sufficiently large echo among the Germans in the province. -

The People of Scarborough

~THE SCARf>OROUGH PuBLIC LIBF{\RY I BOARP THE PEOPLE OF SCARBOROUGH Map of Scarborough ,.; .; .,; ::. .,; .,; .,; "'""- :;, -< "" -< "" "" 'ti "" "" S.teele~ Ave. V IV Finch Avenue III Sileppail.d Ave. 11 D St. REFERENCE POINTS 1. Thomson Park Z. Bluffer's Park J 3. civic Centre 4. Kennedy Subway 5. Metro Zoo Ikml 6. Guild Inn 1 mile! Map of Scarborough courtesy of Rick Schofield, Heritage Scarborough THE PEOPLE OF SCARBOROUGH The City of Scarborough Public Library Board Copyright© The City of Scarborough Public Library Board 1997 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, by photocopying, recording or otherwise for purposes of resale. Published by The City of Scarborough Public Library Board Grenville Printing 25 Scarsdale Rd. Don Mills, Ontario M3B 2R2 Raku ceramic Bicentennial Collector Plate and cover photo by Tom McMaken, 1996. Courtesy of The City of Scarborough. Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data Myrvold, Barbara The People of Scarborough: a history Includes index. ISBN 0-9683086-0-0 1. Scarborough (Ont.) - History. I. Fahey, Curtis, 1951- . II Scarborough Public Library Board. III. Title. FC3099.S33M97 1997 971.3'541 C97-932612-5 F1059.5.T686S35 1997 iv Greetings from the Mayor As Mayor of the City of Scarborough, and on behalf of Members of Council, I am pleased that The People of Scarborough: A History, has been produced. This book provides a chronological overview of the many diverse peoples and cultures that have contributed to the city's economic, cultural and social fabric. -

The Identity of Post World War Ii Ethnic German Immigrants

RELATIVES AND STRANGERS: THE IDENTITY OF POST WORLD WAR II ETHNIC GERMAN IMMIGRANTS By Hans P. Werner A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS Department of History University of Manitoba Winnipeg, Manitoba ©by Hans P. Werner, February 1996 TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract . -. ii Acknowledgments . iv Introduction . • . 1 Chapter One: 'Official' Identity and the Politics of Migration .......................... 10 Chapter Two: The Burden of Memory ......................... ·................... 29 Chapter Three: Reconstructed Identity: The Politics of Socialization ..................... 46 Chapter Four: 'Making It': Work and Consumption .................................. 66 Chapter Five: Family: Kinder, Kuche, Kirche ...................................... 86 Chapter Six: Church, Language and Association: Contesting and Consolidating New Identities .............................................................. 106 Conclusion: Identity as Process . 122 Bibliography ............ -.............................................. 126 i Abstract The years after the end of World War Il were characterized by the constant arrival of new Canadians. ~etween 1946 and 1960, Canada opened its doors to over two mmion ----·--··'"___ ~ .. --immigrants and approximately 13 per cent of them were Geonau. The first ten years of German immigration to Canada were dominated by the arrival of ethnic Germans ..Ethnic Germans. or Volksdeutsche, were German speaking irnn)igrants who were born in countries other than the Germany of 1939. This thesis explores the identity of these ethnic German immigrants. It has frequently been noted that German immigrants to Canada were inordinately quick to adapt to their new society. As a result, studies of German immigrants in Canada have tended to focus on the degree and speed with which they adopted the social framework of the dominant society. -

Deutscher Bund

3.6.2 Deutscher Bund1 The New Germany’s attempts to attract German-Canadians to the National Socialist ideology were carried out by the Deutscher Bund, Canada [Canadian Society for German Culture], organized in January 1934 with its western headquarters located in Winnipeg. It defined itself as the organisierte Volksgemeinschaft des canadischen Deutschtums [the organized Volk community of the German-Canadians];2 its objective was “to unify Germans from coast to coast.” The Bund’s banner was a combination of a swastika and a maple leaf, and its members wore swastika armbands at their meetings. The group published a newspaper from Winnipeg, the Deutsche Zeitung für Canada (see 5.1.4). The Bund spawned local groups with German-language schools, cultural facilities and recreational clubs. Across Canada, it attracted an estimated 2,000 members nationwide (but far fewer in Alberta and B.C. than in Saskatchewan and Ontario3), in part because it claimed to pursue cultural, not political, goals. Its affiliate, the German Labour Front, had an estimated 500 Canadian members. The numbers may appear small, but the Bund had no intention to become a mass organization: it wanted to be an elite group that would train and indoctrinate other Germans in Canada with völkisch beliefs and attitudes. In spite of apparent ideological overlaps with certain other groups the Bund did not have formal associations with Canadian fascist organizations such as the National Unity Party. Karl Gerhard, the group’s leader during its first few years, was an NSDAP member under the direction of the Hamburg-based Auslandsorganisation der NSDAP, which dealt with Party matters abroad. -

DEBATES and PROCEEDINGS

Third Session - Thirty-Eighth Legislature of the Legislative Assembly of Manitoba DEBATES and PROCEEDINGS Official Report (Hansard) Published under the authority of The Honourable George Hickes Speaker Vol. LVI No. 42A - 10 a.m., Thursday, May 5, 2005 MANITOBA LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY Thirty-Eighth Legislature Member Constituency Political Affiliation AGLUGUB, Cris The Maples N.D.P. ALLAN, Nancy, Hon. St. Vital N.D.P. ALTEMEYER, Rob Wolseley N.D.P. ASHTON, Steve, Hon. Thompson N.D.P. BJORNSON, Peter, Hon. Gimli N.D.P. BRICK, Marilyn St. Norbert N.D.P. CALDWELL, Drew Brandon East N.D.P. CHOMIAK, Dave, Hon. Kildonan N.D.P. CULLEN, Cliff Turtle Mountain P.C. CUMMINGS, Glen Ste. Rose P.C. DERKACH, Leonard Russell P.C. DEWAR, Gregory Selkirk N.D.P. DOER, Gary, Hon. Concordia N.D.P. DRIEDGER, Myrna Charleswood P.C. DYCK, Peter Pembina P.C. EICHLER, Ralph Lakeside P.C. FAURSCHOU, David Portage la Prairie P.C. GERRARD, Jon, Hon. River Heights Lib. GOERTZEN, Kelvin Steinbach P.C. HAWRANIK, Gerald Lac du Bonnet P.C. HICKES, George, Hon. Point Douglas N.D.P. IRVIN-ROSS, Kerri Fort Garry N.D.P. JENNISSEN, Gerard Flin Flon N.D.P. JHA, Bidhu Radisson N.D.P. KORZENIOWSKI, Bonnie St. James N.D.P. LAMOUREUX, Kevin Inkster Lib. LATHLIN, Oscar, Hon. The Pas N.D.P. LEMIEUX, Ron, Hon. La Verendrye N.D.P. LOEWEN, John Fort Whyte P.C. MACKINTOSH, Gord, Hon. St. Johns N.D.P. MAGUIRE, Larry Arthur-Virden P.C. MALOWAY, Jim Elmwood N.D.P. MARTINDALE, Doug Burrows N.D.P. -

The Canadian People

VOL. 44, NO. 6 HEAD OFFICE: MONTREAL, JUNE 1963 The CanadianPeople THECENSUS OF 1961provides us witha stock-takingof a numberof birthswhich exceeded the numberin ourselvesin anticipationof Canada’sone-hundredth Quebecfor the first time in a singledecade, increased birthdayas a Confederation. by 35.6 per cent.Quebec’s growth during the ten It is convenientand interesting to divide the report yearswas 29.7per cent,made up of abouta million into sections:How many of us are there? Where by naturalincrease and 205,000by net immigration. do we live? Wheredid we comefrom ? Whatsort of Newfoundland,whose birth-rate was 34 per peopleare we ? Whatare we tryingto become? thousandof the population,considerably over the Thereare manyfigures involved in thissurvey. nationalaverage of 27.5per thousand,increased its Thatis necessary,because the only way to learnwhat totalpopulation by 26.7per cent.Manitoba popula- sortof peoplemake up the Canadiannation is through tionwent up 18.7per cent;Saskatchewan, 11.2 per figures.These figures answer many questions we ask cent; Nova Scotia14.7 per cent; New Brunswick ourselvesfrom time to timewithout having any handy 15.9per cent,and Prince Edward Island 6.3 per cent. wayof findingthe facts. The threemaritime provinces suffered net losses The firstcensus in 1666recorded a totalof 3,215 throughthe excessof emigrationover immigration. peoplein the colonyof New France.By 1763,New Theirbirth-rates varied from 31 to 27 per thousand. Francehad a populationof 60,000,and when the How many workers ? modernnation was formedthrough confederation in For statisticalpurposes the labour force in Canada 1867Canada had 3,500,000people. At the timeof the is definedas all persons14 yearsand overwho are 1961census the totalhad grownto 18,238,247,and eitherworking or lookingfor work.There are, of an estimatemade by the Bureauof Statisticsplaced course,some exclusions: those in the armedforces, thefigure at 18,767,000as we entered1963. -

How Inclusive Are Canadians@150? Public Opinion

How inclusive are Canadians @ 150? Public opinion and vulnerable group experience Presentation to the YMCA Canada National Conference Edmonton, Alberta June 23, 2017 Michael Adams, President Environics Institute for Survey Research Environics Institute for Survey Research • Non-profit research institute founded in 2006 • Mission: To promote relevant and original public opinion and social research on important issues of public policy and social change. • Research focuses on Canada – using social science-based evidence to help organizations and citizens better understand Canada and Canadians - especially those we rarely, if ever, meet. • Wholly separate entity from the commercial Environics companies • All research is publicly released and open source access 2 TheWhy historical survey record…not research greatis important • 1800s: Poor treatment of Irish migrants • 1930s: Anti-semitism (“None is too many”) • 1940s: Internment of Japanese and German Canadians • 21st century: Police profiling racialized minorities • 1800s – today: “Long assault” on Indigenous Peoples But Whysome survey positive research signs is important • 1800s: Welcoming Black American refugees from slavery • 1960s: Opening the door to widespread immigration • Late 1970’s: Accepting 70,000 South-east Asian refugees • 2015: TRC report and 94 “Calls to Action” • 2015-16: Welcoming 35,000 Syrian refugees So how do Canadians feel about their country today? We are proud to be Canadian, even nearly half of Quebec 1985 - 2016 Would you say you are very, somewhat, not very or not -

German-Canadian Studies Fellowship

Department of History Chair in German-Canadian Studies German-Canadian Studies Fellowship 1997-2021 Publications Report Alexander Freund Chair in German-Canadian Studies The University of Winnipeg Report Compiled by Karen Brglez June 2021 E: [email protected] / [email protected] 515 Portage Avenue / Winnipeg / Manitoba / Canada / R3B 2E9 / P: 204.786.9009 / F: 204.774.4134 / http://history.uwinnipeg.ca http://germancanadian.uwinnipeg.ca Summary Between 1997 and 2021, the Chair in German-Canadian Studies at the University of Winnipeg enabled nineteen doctoral students, ten Master’s students, and thirty-nine university and community researchers to conduct high-quality research in the field of German-Canadian Studies. Nine outstanding undergraduate students were awarded the German-Canadian Studies Undergraduate Essay Prize for excellent research essays produced for a variety of courses. The Chair awarded one German-Canadian Studies Master’s thesis Prize and five German-Canadian Studies Dissertation Prizes to outstanding graduate students. In 2019, the program established the German-Canadian Studies Postdoctoral Fellowship to conduct research on German-Canadian migration or German-Canadian relations. One excellent candidate began research in the 2019- 2020 academic year at the University of Winnipeg under the supervision of the Chair in German- Canadian Studies. Fellowship recipients have researched a wide range of topics, from an archeological dig at a former prisoner-of-war camp in Riding Mountain, Manitoba to the encounters between West German citizens and Canadian soldiers in West Germany during the Cold War. Other researchers compared the German communities of Buenos Aires and Kitchener, Ontario as well as the German and Canadian media reporting of the Karl-Heinz Schreiber Affair. -

REDRESS MOVEMENTS in CANADA Editor: Marlene Epp, Conrad Grebel University College University of Waterloo

The Canadian Historical Association No. Immigration And Ethnicity In Canada Series 37 Travis Tomchuk & Jodi Giesbrecht Canadian Museum for Human Rights REDRESS MOVEMENTS IN CANADA Editor: Marlene Epp, Conrad Grebel University College University of Waterloo Series Advisory Committee: Laura Madokoro, McGill University Jordan Stanger-Ross, University of Victoria Sylvie Taschereau, Université du Québec à Trois-Rivières Copyright © the Canadian Historical Association Ottawa, 2018 Published by the Canadian Historical Association with the support of the Department of Canadian Heritage, Government of Canada ISSN: 2292-7441 (print) ISSN: 2292-745X (online) ISBN: 978-0-88798-296-5 Travis Tomchuk is the Curator of Canadian Human Rights History at the Canadian Museum for Human Rights, and holds a PhD from Queen’s University. Jodi Giesbrecht is the Manager of Research & Curation at the Canadian Museum for Human Rights, and holds a PhD from the University of Toronto. Cover image: Japanese Canadian redress rally at Parliament Hill, 1988. Photographer: Gordon King. Credit: Nikkei National Museum 2010.32.124. REDRESS MOVEMENTS IN CANADA Travis Tomchuk & Jodi Giesbrecht Canadian Museum for Human Rights All rights reserved. No part of this publication maybe reproduced, in any form or by any electronic ormechanical means including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the Canadian Historical Association. Ottawa, 2018 The Canadian Historical Association Immigration And Ethnicity In Canada Series Booklet No. 37 Introduction he past few decades have witnessed a substantial outpouring of Tapologies, statements of regret and recognition, commemorative gestures, compensation, and related measures on behalf of all levels of government in Canada in order to acknowledge the historic wrongs suffered by diverse ethnic and immigrant groups.