The Way We Eat Now

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Register Now on Improve Your Premises

FFT.ie International Edition May 2019 Food For Thought THE IRISH HOSPITALITY GLOBAL DIGEST Dublin Beer Cup Awards Who took home the top gongs at this The Mind of the Palate year’s event ..................................p14 with BWG Foodservice The pleasures of the table throughout the event. Spence tray), plus a large conch shell reside in the mind, not is perhaps best known for his with headphones which plays “in the mouth” – perhaps work with Heston Blumenthal, seagulls and crashing waves to the primary message that and Sound of the Sea, the dish evoke a seaside atmosphere Professor Charles Spence of they created in 2007, has been while you eat tasty morsels Somerville College Oxford on the Fat Duck’s menu ever that originated there. has been demonstrating since. “It may seem obvious to us at Catex 2019 in the RDS While the seafood varies with now that the sound of the sea Simmonscourt. the season, the appearance would enhance the experience Grid Finance Professor Spence was of the dish has remained of eating shellfish, but it simply What to look for in your wait staff invited to Catex by BWG much the same - with edible wasn’t before we did it in .......................................................p15 Foodservice and has been sand and foam surrounding 2007,” says Spence. giving fascinating mini- the seafood (and actual sand Spence is proposing nothing symposia at regular times visible below it through a glass less than “a new science of cont. p17 Jägermeister Opens 2019 Scholarship Applications ollowing on from the successful 2018 edition, Jägermeister has opened F In Conversation with.. -

Ireland's Top Places to Eat: the Restaurants and Cafes Serving the Very Best Food in the Country

Technological University Dublin ARROW@TU Dublin Media Publications 2017 Ireland's Top Places to Eat: the Restaurants and Cafes Serving the Very Best Food in the Country Catherine Cleary Irish Times Newspaper Aoife McElwain Irish Times Newspaper Follow this and additional works at: https://arrow.tudublin.ie/gsmed Recommended Citation Cleary, Catherine and McElwain, Aoife, "Ireland's Top Places to Eat: the Restaurants and Cafes Serving the Very Best Food in the Country" (2017). Media. 1. https://arrow.tudublin.ie/gsmed/1 This Other is brought to you for free and open access by the Publications at ARROW@TU Dublin. It has been accepted for inclusion in Media by an authorized administrator of ARROW@TU Dublin. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 4.0 License The 100 best places to eat in Ireland From fish-finger sandwiches to fine dining, we recommend the restaurants and cafes serving the best food in the country Sat, Mar 18, 2017, 06:00 Updated: Sat, Mar 18, 2017, 12:01 Catherine Cleary, Aoife McElwain 7 Video Images Good value: * indicates main course for under €15 CAFES Hatch and Sons Irish Kitchen* The Little Museum of Dublin, 15 St Stephens Green, Dublin 2. 01-6610075. hatchandsons.co The people behind Hatch and Sons could just have traded on their looks, with their basement kitchen on Stephens Green like a timepiece from an Upstairs Downstairs set. But they reached a bit further and made the cafe at the bottom of The Little Museum of Dublin a showpiece for Irish ingredients. -

15Th September

7 NIGHTS IN LISBON INCLUDINGWIN! FLIGHTS 2019 6th - 15th September www.atasteofwestcork.com Best Wild Atlantic Way Tourism Experience 2019 – Irish Tourism & Travel Industry Awards 1 Seaview House Hotel & Bath House Seaview House Hotel & Bath House Ballylickey, Bantry. Tel 027 50073 Join us for Dinner served nightly or Sunday [email protected] House in Hotel our Restaurant. & Bath House Perfect for Beara & Sheep’s Head walkingAfternoon or aHigh trip Tea to theor AfternoonIslands Sea served on Saturday by reservation. September 26th – 29th 2019 4 Star Country Manor House Enjoy an Organic Seaweed Hotel, set in mature gardens. Enjoy an Organic Seaweed Bath in one IARLA Ó LIONÁIRD, ANTHONY KEARNS, ELEANOR of Bathour Bath in one Suites, of our or Bath a Treatment Suites, in the Highly acclaimed by ornewly a Treatment developed in the Bath newly House. SHANLEY, THE LOST BROTHERS, YE VAGABONDS, Michelin & Good Hotel developed Bath House with hand Guides as one of Ireland’s top 4**** Manor House Hotel- Ideal for Small Intimate Weddings, JACK O’ROURKE, THOMAS MCCARTHY. craftedSpecial woodburning Events, Private Dining outdoor and Afternoon Tea. destinations to stay and dine saunaSet within and four ac rhotes of beaut tub;iful lya manicu perfectred and mature gardens set 4**** Manor House Hotel- Ideal for Small Intimate Weddings, back from the Sea. Seaview House Hotel is West Cork’s finest multi & 100 best in Ireland. recoverySpecial followingEvents, Private Diningactivities and Afternoon such Tea. award winning Country Manor Escape. This is a perfect location for discovering some of the worlds most spectacular scenery along the Wild ****************** Set withinas four walking acres of beaut andifully manicu cycling.red and mature gardens set Atlantic Way. -

'Food & Wine' December 2010

Food & Wine December 2010 PRICE £2.50 The Journal of The International Wine & Food Society Europe & Africa Committee Free to European & African Region Members - one per address - Issue 105 A Woman with a Mission Dispatches from the Fairest Cape The True Roast Beef of Old England © The Hereford Cattle Society CONTRIBUTORS Darina Allen has been acclaimed as the “Julia Child of Ireland”. Her fifteenth book, „Forgotten Skills of Cooking‟ is CHAIRMAN’S a treasure trove of recipes. At 61 Darina still has more energy than many of her students at her cookery school. In an MESSAGE interview for The Irish Times she explained that her mission in life is to educate the next generation in the “forgotten skills”. Martin Fine who was born in Birkenhead, graduated Dear Members from Cardiff College of Food Technology and com- I send my heartfelt sympathy and prayers to the incoming Society Chairman Alec menced his hotel career at Murray. With his wife, Irene, he travelled from his home in Canada for the annual „face the famous Grosvenor to face‟ meeting of Council and the Regional Festival in Sydney. Whilst Alec attended House Hotel, London and the Council meeting that confirmed his new position Irene fell down stairs in the hotel the George V in Paris. Library and badly broke her leg. She has now had 3 operations and there have been further complications resulting in their return home being indefinitely postponed. While working in France It is only 3 months since I last wrote a Chairman‟s column but they have been he met his wife, Pauline, a very eventful. -

New Irish Cuisine a Comprehensive Study of Its Nature and Recent Popularity

New Irish cuisine A comprehensive study of its nature and recent popularity An MSc thesis New Irish cuisine A comprehensive study of its nature and recent popularity Pedro Martínez Noguera [email protected] 950723546110 Study program: MSc Food Technology (MFT) Specialisation: Gastronomy Course code: RSO-80433 Rural Sociology Supervisor: dr. Oona Morrow Examiner: prof.dr.ing. JSC Wiskerke June, 2020 Acknowledgements I would like to express my sincere gratitude to various people without whom nothing of this would have been possible. First, thank you Oona for your fantastic supervision. Digging into the sociology of food has been truly eye-opening. Second, many thanks to all the warmhearted Irish people I have had the pleasure to meet throughout this journey: chefs, foodies, colleagues of the postgrad office at UCC, and the marvelous friends I made in Cork and Galway. Third, thanks to Irene and Gio. Their generosity deserves space on these lines. Finally, this thesis is especially dedicated to my family, my brothers and particularly my parents, for their incalculable support and for having let me freely pursue all my dreams. 3 Abstract Irish gastronomy has experienced a great transformation in the last couple of decades. High-end restaurants have gone from being predominantly French or British throughout the 20th century to depicting today a distinctive Irish tone. I have referred to this fashion as new Irish cuisine (NIC), a concept that attempts to enclose all fine-dining ventures that serve modern Irish food in Ireland and their common cooking ethos. This research has aimed to investigate thoroughly the nature of this culinary identity from a Bourdieuian perspective and to contextualize its emergence. -

Copyrighted Material

Index A Arklow Golf Club, 212–213 Bar Bacca/La Lea (Belfast), 592 Abbey Tavern (Dublin), 186 Armagh, County, 604–607 Barkers (Wexford), 253 Abbey Theatre (Dublin), 188 Armagh Astronomy Centre and Barleycove Beach, 330 Accommodations, 660–665. See Planetarium, 605 Barnesmore Gap, 559 also Accommodations Index Armagh City, 605 Battle of Aughrim Interpretative best, 16–20 Armagh County Museum, 605 Centre (near Ballinasloe), Achill Island (An Caol), 498 Armagh Public Library, 605–606 488 GENERAL INDEX Active vacations, best, 15–16 Arnotts (Dublin), 172 Battle of the Boyne Adare, 412 Arnotts Project (Dublin), 175 Commemoration (Belfast Adare Heritage Centre, 412 Arthur's Quay Centre and other cities), 54 Adventure trips, 57 (Limerick), 409 Beaches. See also specifi c Aer Arann Islands, 472 Arthur Young's Walk, 364 beaches Ahenny High Crosses, 394 Arts and Crafts Market County Wexford, 254 Aille Cross Equestrian Centre (Limerick), 409 Dingle Peninsula, 379 (Loughrea), 464 Athassel Priory, 394, 396 Donegal Bay, 542, 552 Aillwee Cave (Ballyvaughan), Athlone Castle, 487 Dublin area, 167–168 433–434 Athlone Golf Club, 490 Glencolumbkille, 546 AirCoach (Dublin), 101 The Atlantic Highlands, 548–557 Inishowen Peninsula, 560 Airlink Express Coach Atlantic Sea Kayaking Sligo Bay, 519 (Dublin), 101 (Skibbereen), 332 West Cork, 330 Air travel, 292, 655, 660 Attic @ Liquid (Galway Beaghmore Stone Circles, Alias Tom (Dublin), 175 City), 467 640–641 All-Ireland Hurling & Gaelic Aughnanure Castle Beara Peninsula, 330, 332 Football Finals (Dublin), 55 (Oughterard), -

ROTYA 2017 Shortlists UPDATE for Press Release.Indd

Café of the Year Hotel Restaurant Restaurant with Best for Wine Best for Brunch Award of the Year Award Rooms Award Lovers Award Award Assassination Custard, George V, Aldridge Lodge, 64 Wine, Brother Hubbard North, Dublin 8 Ashford Castle, New Ross, County Wexford Sandycove, Dublin 1 County Mayo County Dublin Country Choice, Blairscove Restaurant, Cloud Café, Nenagh, County Tipperary Gregans Castle Hotel, Durrus, County Cork Chapter One, North Strand, County Clare Dublin 1 Dublin 3 Deanes Deli Bistro, Inis Meáin Restaurant Belfast La Fougere, & Suites, Aran Islands, Forest & Marcy, Eastern Seaboard Knockranny House Hotel, County Galway Dublin 4 Bar & Grill, Dooks Fine Foods, County Mayo County Louth Fethard, Tipperary MacNean House and Green Man Wines, Longueville House Hotel, Restaurant, Blacklion, Dublin 6 Hadskis, Firehouse Bakery, County Cork County Cavan Belfast Delgany, County Wicklow L’attitude 51 Wine Café, AN River Room Restaurant, QC’s Seafood Restaurant Cork Herbstreet Restaurant, L D Grow HQ, E ’S Galgorm Resort & Spa, and Townhouse, Dublin 2 R Waterford Ox, I Antrim Cahersiveen, County Kerry Belfast Meet Me In The Morning, Kalbos Café, Tavern at The Dylan Hotel, Rayanne House, Dublin 8 A Skibbereen, County Cork Dublin 4 Holywood, County Down Piglet Wine Bar, W 7 Dublin 2 Roberta’s, 1 Press Café, Dublin 2 A 0 The Catalina Restaurant, King Sitric Restaurant R 2 The National Print Museum, Lough Erne Resort, & Accommodation, Restaurant Patrick D S Dublin 4 Guilbaud, Dublin 2 San Lorenzo’s, County Fermanagh Howth, County Dublin Dublin 2 The Farmgate Café, The Lady Helen Restaurant, The Old Convent, The Black Pig, Old English Market, Cork Kinsale, Cork The Fumbally, Mount Juliet, Kilkenny Cahir, County Tipperary Dublin 8 Two Boys Brew, Whelehans, The Marker Hotel, The Tannery, Two Boys Brew, Dublin 7 Dublin 2 Dungarvan, The Silver Tassie, The shortlist Dublin 18 Dublin 7 County Waterford The Mitre, We’re excited to announce the shortlist for the all-new FOOD&WINE Awards 2017. -

TU Dublin School of Culinary Arts and Food Technology Newsletter Autumn 2019

TU Dublin School of Culinary Arts and Food Technology Newsletter Autumn 2019 Joint first place for David & Eugenia at International Competition. Congratulations to David Hurley and Eugenia Xynada from TU sisting both David and Eugenia throughout their preparations and Dublin, School of Culinary Arts and Food Technology who participation in this prestigious International competition. achieved joint first place in the student category of the Note by http://www2.agroparistech.fr/The-event.html Further report details Note contest which took place at AgroParisTech, Paris re- (AgroParisTech, Paris). cently. Both students are undertaking the Advanced Molecular https://www.dit.ie/newsandevents/news/archive2019/news/title175000en.html Gastronomy module on their programme studies. The final took Update (TU Dublin’s Newsletter) report. place following the 9th International Workshop of Molecular and Physical Gastronomy, attended by scientists and professors from 15 countries. Competitors from 20 countries were required to prepare dishes that used as many pure compounds as possible without fruits, vegetable, meat, fish or spices. The jury which included chef Patrick Terrien, Yolanda Rigault, Michael Pontif, and Sandrine Kault-Perrin, also evaluated the students on innovation, complexity and flavour. According to Dr. Roisin Burke, Senior Lecturer, TU Dublin, the dishes created by the two students met the judges' criteria. "David created a cocktail which appeared as Eggnog but tasted of bacon, and what appeared to be a bacon crisp but had a flavour of Eggnog. His main dish included a Note by Note beetroot protein cake, horseradish jelly and beetroot cremeaux. It was presented in the form of a meat muscle and put under a smoked filled lid." For her part, Eugenia created a Note by Note version of a breakfast dish with what appeared to be eggs, layered pork sausage and jellied beans, bacon flakes and the tomato element were created in the form of a Note by Note ‘Bloody Mary’ cocktail. -

Ireland IRELAND

Ireland I.H.T. Airports - with unpaved runways: total: 27 914 to 1,523 m: 2 under 914 m: 25 IRELAND (1999 est.) Visa: not required from nationals of the EU, America, Canada, and Japan Duty Free: goods permitted: 200 cigarettes or 100 cigarillos or 50 cigars or 250g of tobacco, 1 litre of spirits (more than 22%) or 2 litres of other alcoholic beverages, including sparking or fortified wine, plus 2 litres of table wine, 50g of perfume and 250ml of eau de toilette, goods to the value of IR£32 Health: no specific precautions. HOTELS●MOTELS●INNS ACHILL ISLAND MAYO GRAY'S GUESTHOUSE,Dugort, Achill Island, Co. Mayo.,Tel: 098 43244 or 098 43315, [email protected] , www.grays-guesthouse.ie ANTRIM BALLYCASTLE MARINE HOTEL 1-3 NORTH STREET, BALLYCASTLE CO. ANTRIM BALLYCASTLE ANTRIM IRELAND 012657-62222 012657-69507, [email protected] , http://www.marinehotel.net ANTRIM BROUGHSHANE TULLYMORE HOUSE 2 CARNLOUGH ROAD, BROUGHSHANE BALLYMENA, CO. ANTRIM BROUGHSHANE ANTRIM IRELAND 01266-861233 01266- 862238 ANTRIM PORTBALLINTRAE BEACH HOUSE HOTEL 61 BEACH ROAD, PORTBALLINTRAE BUSHMILLS, Country Dialling Code (Tel/Fax): ++353 CO. ANTRIM PORTBALLINTRAE ANTRIM IRELAND 012657-31214 Bord failte Eireann: Baggot Street Bridge Dublin 2 Tel: (1) 602 4000 Fax: (1) 602 , 012657-31664 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.ireland.travel.ie ANTRIM PORTRUSH Europe Map References: EGLINTON HOTEL 49 EGLINTON STREET, PORTRUSH CO. ANTRIM total: 70,280 sq km land: 68,890 sq km water: 1,390 sq km Area: PORTRUSH ANTRIM IRELAND 01265-822371 01265-823155 , Climate: temperate maritime; modified by North Atlantic Current; mild winters, cool [email protected] summers; consistently humid; overcast about half the time MAGHERABUOY HOUSE HOTEL 41 MAGHERABOY ROAD PORTRUSH, CO. -

From the Dark Margins to the Spotlight: the Evolution of Gastronomy and Food Studies in Ireland

Technological University Dublin ARROW@TU Dublin Books/Book Chapters School of Culinary Arts and Food Technology 2021 From the Dark Margins to the Spotlight: The Evolution of Gastronomy and Food Studies in Ireland Máirtín Mac Con Iomaire Technological University Dublin, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://arrow.tudublin.ie/tschafbk Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Mac Con Iomaire, M. (2021) ‘From the Dark Margins to the Spotlight: The Evolution of Gastronomy and Food Studies in Ireland’, in Catherine Maignant, Sylvain Tondour and Déborah Vandewoude (eds), Margins and Marginalities in Ireland and France: A Socio-cultural Perspective (Oxford: Peter Lang, 2021), 129-153. This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Culinary Arts and Food Technology at ARROW@TU Dublin. It has been accepted for inclusion in Books/Book Chapters by an authorized administrator of ARROW@TU Dublin. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 4.0 License 1 From the Dark Margins to the Spotlight: The Evolution of Gastronomy and Food Studies in Ireland Máirtín Mac Con Iomaire, Technological University Dublin, Ireland For many years, food was seen as too quotidian and belonging to the domestic sphere, and therefore to women, which excluded it from any serious study or consideration in academia.1 This chapter tracks the evolution of gastronomy and food studies in Ireland. It charts the development of gastronomy as a cultural field, originally in France, to its emergence as an academic discipline with a particular Irish inflection. -

Dublin Institute of Technology, Dublin Máirtín Mac Con Iomaire Identified by Taste: the Chef As Artist?

Mac Con Iomaire The chef as artist Dublin Institute of Technology, Dublin Máirtín Mac Con Iomaire Identified by taste: the chef as artist? Abstract: This article discusses the role of taste among the senses using fictional depictions of taste, including Proust’s madeleine episode; Suskind’s Perfume: the story of a murderer; Esquivel’s Como aqua para chocolate; Harris’s Chocolate and Blixen’s Babette’s feast. The discussion also provides three historical case studies which highlight how an individual chef was identified against the odds by the individualistic taste of his or her cooking. Biographical note: Dr. Máirtín Mac Con Iomaire is a lecturer in culinary arts in the Dublin Institute of Technology. He was the first Irish chef to be awarded a PhD, for his research on the Influence of French haute cuisine on the emergence and development of Dublin restaurants, using oral history. He is a regular attendee and contributor at the Oxford Symposium on Food & Cookery. He is also keen contributor to the media and has hosted two series of cookery programmes for Irish television. He is the founding chair of the Dublin Gastronomy Symposium and co-editor of ‘Tickling the palate’: gastronomy in Irish literature and culture published by Peter Lang (2014). Keywords: Creative writing – Taste – Food writing – Fiction – Chefs TEXT Special Issue 26: Taste and, and in, writing and publishing 1 eds Donna Lee Brien and Adele Wessell, April 2014 Mac Con Iomaire The chef as artist The American sociologist Gary Alan Fine has studied professional kitchens and described the work of chefs as ranging from that of artist to that of manual labourer. -

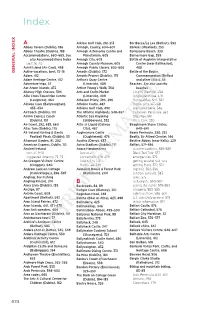

Restaurant Index

15_598929_bindex.qxd 8/4/06 12:05 PM Page 407 ACCOMMODATIONS INDEX Note: Page numbers of accommodation profiles are in boldface type. A Conrad Hotel, Dublin, 111 Crescent Townhouse, Belfast, 370, 373–74 Abbeyglen Castle Hotel, Clifden, 300, 327–28 Adare Country House, Adare, 269–70 D Adare Manor, Adare, 29, 93, 270–71 Days Inn Talbot Street, Dublin, 111 Ashford Castle, Cong, 93, 300, 332–33 Delphi Mountain Resort and Spa, Westport, Ash-Rowan House, Belfast, 370, 372, 373 300, 333–34 Atlantic Coast Doyle’s Townhouse, Dingle, 237, 256 Doolin, 299, 300 Dromoland Castle, Ennis, 93, 270, 286–87 Westport, 300, 333 Dunraven Arms, Adare, 270, 271–72 Avenue House, Belfast, 370, 372–73 F B The Fitzwilliam, Dublin, 31, 112, 113, 115 Ballymaloe House, Midleton, 29, 186, 216 Foley’s, Kenmare, 236, 237 Ballynahinch Castle, Recess, 30, 300, 328 Foyles Hotel, Clifden, 300, 328–29 Barnabrow Country House, Midleton, 186, Frewin, North Donegal, 30, 342, 362 216–17 Friar’s Lodge, Kinsale, 186, 225–26 Bewleys Hotel, Dublin, 112, 113–14 Brownes Hotel, Dublin, 112, 113, 114 G Bushmills Inn, Antrim Coast, 30, 373, 400–401 Glenlo Abbey, Galway, 300, 312, 317 Butler Court, Kilkenny, 184, 186–87 Glenview House, Midleton, 30, 186, 217–18 Butler House,COPYRIGHTED Kilkenny, 184, 186, 187 Great Southern MATERIAL Hotel, Galway, 300, 312–13, 317 C Greenmount House, Dingle, 30, 237, Captains House, Dingle, 237, 255 256–57 Castle Grove Country House Hotel, North The Gresham, Dublin, 112, 113, 115–16 Donegal, 342, 361–62 Castlewood House, Dingle, 237, 255–56 H Chart House,