Peat and the Dutch Golden Age

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Regio Het Gooi Stads Taxi Prijzen: Hilversum: Hilversum – Hilversum 9

Regio Het Gooi Stads Taxi prijzen: Hilversum: Hilversum – Hilversum 9,50, Hilversum – Bussum 14,50, Hilversum – Naarden 19,50, Hilversum – Laren 14,50, Hilversum – Blaricum 19,50, Hilversum – Huizen 19,50, Hilversum – Eemnes 19,50, Hilversum – Baarn 14,50, Hilversum – Kortenhoef 14,50, Hilversum – s’Graveland 14,50, Hilversum – Nederhorst de berg 19,50, Hilversum – Ankeveen 14,50, Hilversum – Weesp 19,50, Hilversum – Muiden 19,50, Hilversum – Nigtevecht 19,50, Hilversum – Loenen a/d vecht 19,50, Hilversum – Vreeland 19,50, Hilversum – Loosdrecht 14,50 Bussum: Bussum – Bussum 9,50, Bussum – Hilversum 14,50, Bussum – Naarden 14,50, Bussum – Laren 14,50, Bussum – Blaricum 14,50, Bussum – Huizen 14,50, Bussum – Eemnes 19,50, Bussum – Baarn 19,50, Bussum – Kortenhoef 14,50, Bussum – s’Graveland 14,50, Bussum – Nederhorst den berg 19,50, Bussum – Ankeveen 14,50, Bussum – Weesp 19,50, Bussum – Muiden 19,50, Bussum – Nigtevecht 19,50, Bussum – Loenen a/d vecht 19,50, Bussum – Vreeland 19,50, Bussum – Loosdrecht 19,50 Naarden: Naarden – Naarden 9,50, Naarden – Hilversum 19,50, Naarden – Bussum 14,50, Naarden – Laren 14,50, Naarden – Blaricum 14,50, Naarden – Huizen 14,50, Naarden – Eemnes 19,50, Naarden – Baarn 19,50, Naarden – Kortenhoef 19,50, Naarden – s’Graveland 19,50, Naarden – Nederhorst den berg 19,50, Naarden – Ankeveen 19,50, Naarden – Weesp 14,50, Naarden – Muiden 14,50, Naarden – Nigtevecht 19,50, Naarden – Loenen a/d vecht 19,50, Naarden – Vreeland 19,50, Naarden – Loosdrecht 19,50 Laren: Laren – Laren 9,50, Laren – Hilversum 14,50, -

Fietsspeurtocht

Fietsspeurtocht Welkom bij de Fietsspeurtocht! Deze tocht is voor jong en oud. Bij elke locatie krijg je een vraag en moet je een antwoord geven. De letters uit de antwoorden vormen een zin. Deze kun je aan het einde van de tocht oplossen. Je kunt op elke locatie starten! De route is ca. 30 kilometer, dus wees goed voorbereid! Wat neem je mee en trek je aan? Neem iets te eten, drinken en eventueel een lekkere snack mee. Pleisters, mobiele telefoon en een vrolijke lach op je gezicht. Trek makkelijk zittende kleding aan en kleed je naar hoe het weer is. Onderweg kom je ook langs plekken waar je iets kunt kopen. Gooise Meren Beweegt is onderdeel van Sportfondsen Gooise Meren. Fietsspeurtocht Molen ‘de Onrust’ Molen ‘De Onrust’ is gebouwd in 1809 om het Naardermeer te be- malen. De 15 meter hoge molen regelt het waterpeil van dit bijna 700 ha grote moerasgebied, zonder ondersteuning van een ander gemaal. In het Naardermeer wordt de natuur met natuurlijke kracht onderhouden. Het scheprad verplaatst ongeveer 10 m³ water per omwenteling. Het wiekenkruis draait hiervoor twee keer rond. Om een peilverlaging van 1 cm te krijgen, is één dag (ongeveer 16 uur) met goede wind nodig. Door de wieken in een bepaalde stand stil te zetten kun je snel een boodschap doorgeven. Handig toen er nog geen telefoon was! Wieken in een plusteken betekent 'rust', wieken in een kruis met de hoogste wiek vlak voor het hoogste punt betekent 'vreugde'. Waterhuishouding Naardermeer Het Naardermeergebied heeft een eigen waterhuishouding. Vroeger was er genoeg water in het Naardermeer. -

Weesp, Almere/Hilversum, Utrecht

richting/direction Weesp, Almere/Hilversum, Utrecht AlmereAlmere PoortAlmere MuziekwijkAlmere CentrumAlmere ParkwijkAlmere Buiten Oostvaarders AmsterdamDuivendrechtDiemen RAI Weesp Zuid _` ` ` ` ` Naarden-BussumBussumHilversum ZuidHilversum MediaHilversumHollandsche Park SportparkUtrechtUtrecht Rading Overvecht Centraal ` _` ` _` De informatie op deze vertrekstaat kan zijn gewijzigd. Plan uw reis op ns.nl, in de app of raadpleeg de schermen met actuele vertrekinformatie op dit station. The information on this board may be subject to changes. Check your journey plan on ns.nl or consult the displays with real-time travel information at this station. Vertrektijd/ Treinen rijden op/ Spoor/ Soort trein/ Eindbestemming/ Vertrektijd/ Treinen rijden op/ Spoor/ Soort trein/ Eindbestemming/ Departure Trains run on Platf. Transportation Destination Departure Trains run on Platf. Transportation Destination 52 ma di wo do vr 2 Sprinter Utrecht Centraal via Duivendrecht-Weesp- 06 ma di wo do vr za zo 2 Sprinter Almere Oostvaarders via Duivendrecht-Weesp- 5 Naarden-Bussum-Hilversum 16 Almere C. 22 ma di wo do vr za zo 2 Sprinter Utrecht Centraal via Duivendrecht-Weesp- 06 ma di wo do vr 2 Sprinter Almere Oostvaarders via Duivendrecht-Weesp- Naarden-Bussum-Hilversum 6 Almere C. 36 ma di wo do vr za zo 2 Sprinter Almere Oostvaarders via Duivendrecht-Weesp- 22 ma di wo do vr 2 Sprinter Utrecht Centraal via Duivendrecht-Weesp- Almere C. Naarden-Bussum-Hilversum 52 ma di wo do vr za zo 2 Sprinter Utrecht Centraal via Duivendrecht-Weesp- 36 ma di wo do vr 2 Sprinter Almere Oostvaarders via Duivendrecht-Weesp- Naarden-Bussum-Hilversum Almere C. 52 ma di wo do vr za 2 Sprinter Utrecht Centraal via Duivendrecht-Weesp- 06 ma di wo do vr za zo 2 Sprinter Almere Oostvaarders via Duivendrecht-Weesp- Naarden-Bussum-Hilversum 17 Almere C. -

Living with Rivers Netherland Plain Polder Farmers' Migration to and Through the River Flatlands of the States of New York and New Jersey Part I

Living with Rivers Netherland Plain Polder Farmers' Migration to and through the River Flatlands of the states of New York and New Jersey Part I 1 Foreword Esopus, Kinderhook, Mahwah, the summer of 2013 showed my wife and me US farms linked to 1700s. The key? The founding dates of the Dutch Reformed Churches. We followed the trail of the descendants of the farmers from the Netherlands plain. An exci- ting entrance into a world of historic heritage with a distinct Dutch flavor followed, not mentioned in the tourist brochures. Could I replicate this experience in the Netherlands by setting out an itinerary along the family names mentioned in the early documents in New Netherlands? This particular key opened a door to the iconic world of rectangular plots cultivated a thousand year ago. The trail led to the first stone farms laid out in ribbons along canals and dikes, as they started to be built around the turn of the 15th to the 16th century. The old villages mostly on higher grounds, on cross roads, the oldest churches. As a sideline in a bit of fieldwork around the émigré villages, family names literally fell into place like Koeymans and van de Water in Schoonrewoerd or Cool in Vianen, or ten Eyck in Huinen. Some place names also fell into place, like Bern or Kortgericht, not Swiss, not Belgian, but Dutch situated in the Netherlands plain. The plain part of a centuries old network, as landscaped in the historic bishopric of Utrecht, where Gelder Valley polder villages like Huinen, Hell, Voorthuizen and Wekerom were part of. -

Naardermeer Nature Reserve (Netherlands)

Strasbourg, 2 January 2003 PE-S-DE (2002) 24 [diplome/docs/2003/de24e_03] Committee for the activities of the Council of Europe in the field of biological and landscape diversity (CO-DBP) Group of specialists – European Diploma for Protected Areas 20-21 January 2003 Room 2, Palais de l'Europe, Strasbourg Naardermeer Nature Reserve (Netherlands) Application for the European Diploma for Protected Areas Document established by the Directorate of Culture and Cultural and Natural Heritage This document will not be distributed at the meeting. Please bring this copy. Ce document ne sera plus distribué en réunion. Prière de vous munir de cet exemplaire. PE-S-DE (2003) 24 2 Council of Europe European Diploma Information form For Candidate Sites Site code 1. SITE IDENTIFICATION 1.1 SITE NAME NAARDERMEER 1.2 COUNTRY NETHERLANDS 1.3 DATE CANDIDATURE 1.4 SITE INFORMATION COMPILATION DATE 3 PE-S-DE (2003) 24 1.5 ADDRESSES: administrative Authorities National Authority Regional Authority Local Authority Ministerie van Landbouw, Provincie Noord Holland Gemeente Naarden Natuurbeheer en Visserij Dreef 3 Raadhuisstraat 2 Bezuidenhoutseweg 73 Postbus 123 1411EC NAARDEN Postbus 20401 2000 MD HAARLEM tel: 035-6957811 2500 EK DEN HAAG Tel. + 31 23 514 31 43 tel. + 31 70 3785770 Fax + 31 23 514 40 40 fax +31 70 3786146 Gemeente Hilversum Postbus 9900 1201 GM HILVERSUM Tel. 035 - 629 2111 Telefax : 035-6292129 E-mail : [email protected] Gemeente Muiden Postbus3 1398 ZG MUIDEN Telefoon 0294-210210 Telefax : 0294-261386 E-mail : [email protected] Gemeente Weesp Postbus 5099 1380 GB WEESP Telefoon 0294-491391 Telefax 0294-414251 E-mail [email protected] 1.6 ADRESSES: Site Authorities Site manager Site information Centre Council of Europe Contact G. -

Understanding Water Use Conflicts to Advance Collaborative Planning

water Article Understanding Water Use Conflicts to Advance Collaborative Planning: Lessons Learned from Lake Diefenbaker, Canada Jania S. Chilima 1,*, Jill Blakley 1,2, Harry P. Diaz 3 and Lalita Bharadwaj 1,4 1 School of Environment and Sustainability, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, SK S7N 5C8, Canada; [email protected] (J.B.); [email protected] (L.B.) 2 Department of Geography and Planning, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, SK S7N 5C8, Canada 3 Department of Sociology and Social Studies, University of Regina, Regina, SK S4S 0A2, Canada; [email protected] 4 School of Public Health, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, SK S7N 2Z4, Canada * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-306-262-6920 Abstract: Conflicts around the multi-purpose water uses of Lake Diefenbaker (LD) in Saskatchewan, Canada need to be addressed to meet rapidly expanding water demands in the arid Canadian prairie region. This study explores these conflicts to advance collaborative planning as a means for improving the current water governance and management of this lake. Qualitative methodology that employed a wide participatory approach was used to collect focus group data from 92 individuals, who formed a community of water users. Results indicate that the community of water users is unified in wanting to maintain water quality and quantity, preserving the lake’s aesthetics, and reducing water source vulnerability. Results also show these users are faced with water resource conflicts resulting from lack of coherence of regulatory instruments in the current governance regime, Citation: Chilima, J.S.; Blakley, J.; and acceptable management procedures of both consumptive and contemporary water uses that Diaz, H.P.; Bharadwaj, L. -

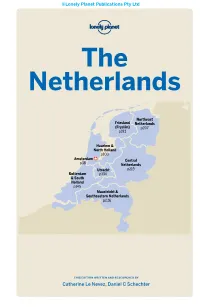

The Netherlands 6

©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd The Netherlands Northeast Friesland Netherlands (Fryslân) p207 p193 Haarlem & North Holland p100 #_ Amsterdam Central p38 Netherlands Utrecht p219 Rotterdam p134 & South Holland p145 Maastricht & Southeastern Netherlands p236 THIS EDITION WRITTEN AND RESEARCHED BY Catherine Le Nevez, Daniel C Schechter PLAN YOUR TRIP ON THE ROAD Welcome to the AMSTERDAM . 38 Texel . 121 Netherlands . 4 Muiden . 129 The Netherlands’ Map . 6 HAARLEM & NORTH Het Gooi . 130 The Netherlands’ HOLLAND . 100 Flevoland . 132 Top 10 . .. 8 North Holland . 102 Lelystad . 132 Need to Know . 14 Haarlem . 102 Urk . 133 Around Haarlem . 107 What’s New . 16 Zaanse Schans . 107 UTRECHT . 134 If You Like… . 17 Waterland Region . 108 Utrecht City . 135 Month by Month . 20 Alkmaar . 112 Around Utrecht City . 142 Itineraries . 23 Broek op Langedijk . 115 Kasteel de Haar . 142 Hoorn . 116 Utrechtse Heuvelrug Cycling in National Park . 142 the Netherlands . 26 Enkhuizen . 118 Medemblik . 120 Amersfoort . 143 Travel with Children . 31 Den Helder . 121 Oudewater . 144 Regions at a Glance . 34 STEVEN SWINNEN / GETTY IMAGES © IMAGES GETTY / SWINNEN STEVEN JEAN-PIERRE LESCOURRET / GETTY IMAGES © IMAGES GETTY / LESCOURRET JEAN-PIERRE CUBE HOUSES, ROTTERDAM P148 AMOSS / LONELY PLANET © PLANET LONELY / AMOSS DUTCH TULIPS P255 BRIDGE OVER SINGEL CANAL, AMSTERDAM P73 Contents UNDERSTAND ROTTERDAM Northwest Groningen . 215 The Netherlands & SOUTH Hoogeland . 215 Today . 252 HOLLAND . 145 Bourtange . 216 History . 254 South Holland . 147 Drenthe . 217 The Dutch Rotterdam . 147 Assen . 217 Way of Life . 264 Around Rotterdam . 161 Kamp Westerbork . 218 Dutch Art . 269 Dordrecht . 162 Dwingelderveld Architecture . 276 Biesbosch National Park . 218 National Park . 165 The Dutch Slot Loevestein . -

Langs Historische Plaatsen in Gooise Meren

Van Muiderberg naar Muiden (10 km) Van Muiden naar Bussum (14 km) Langs historische • Brink • terug: Weesperweg ð Amsterdamsestraat ï Zeestraat 8 Wilhelminaboom, Heinze monument [17] uitzicht bij Westbatterij 1851 • ñ Dorpsstraat Badlaan ï Zeeweg • terug ï, na de brug bij de Groote Zeesluis ð Herengracht plaatsen in 9 strand en uitzicht op Ymeer; Muiderberg is een stuw RK Heilige Nicolaaskerk, waterstaatskerk 1821 walopduiking in het veen met zand, grint, leem • ï Kerkstraat Gooise Meren • ï Flevolaan ð Brink Grote of Sint Nicolaaskerk uit 1400 met beeld Liudger (742809), missionaris, in tuin van Boskapel tufstenen toren uit 1150 bij Floriskei • ï Kloosterstraat ð Naarderstraat Tussen Middeleeuwen 11 • ñ ð Kerkpad • Richting Naarden, Zuidpolderweg langs Naardertrekvaart Kerkaanzee, 15e eeuw betonnen schuilplaatsen jaren ’30 in weilanden en 21e Eeuw [13] kerkaanzee, Muiderberg • bij Hakkelaarsbrug ð De Goog, viaduct over A1 De Goog • terug ð en volg Dijkweg en Noordpolderdijk over ruim [18] Molen de Onrust (1809) bij Naardermeer 4 km • ï en volg Meerkade en Overscheenseweg over 5 km langs zicht op Muiderslot en Naardermeer [14] Vesting Muiden [19] Naardermeer, natuurmonument, tevergeefs 10 drooggelegd in 1883 Stadzigt van Natuurmonumenten (koffie) • Voormeer ñ Gr W de Oudelaan ð Kon.Wilhelminalaan C. v.d. Lindenlaan ï Verl Fortlaan ð Santmannlaan [20] Houten huizen in verboden kring van Karnemelkslootforten. • ñ Floralaan Gudelalaan ð Koningslaan ï Beerensteinerlaan links Kom van Biegel 12 13 14 15 • ð Nieuwe Hilversumseweg Bussum, Naarden, Muiderberg en Muiden vormen Majellakapel/NPB • ð Ton Kootsingel • ð Iepenlaan ð TOP/Zandzee vanaf 2016 de gemeente Gooise Meren. -

Bijlage 1. Behorende Bij Artikel 8. Lid 3 Van Het Uitvoeringsbesluit Afvalstoffenverordening Regio Gooi En Vechtstreek 2020

Bijlage 1. Behorende bij Artikel 8. lid 3 van het Uitvoeringsbesluit Afvalstoffenverordening Regio Gooi en Vechtstreek 2020 Scholen/verenigingen e.d. die aangewezen zijn voor inzamelen papier en karton: (Bos)Hoeve, Smeekweg 98102 1251 VK LAREN 2e Montessorischool, Holleblok 10 1273 EG HUIZEN Alberdingk Thijm College, Laapersveld 9 1213 VB HILVERSUM Altius H'sum Voetbalvereniging, Kininelaantje 67 1216 BZ HILVERSUM Amaris de Veste, Anna van Burenlaan 2a 1411 EK NAARDEN Amicitia muziekvereniging, Postbus 185 1243ZK 'S GRAVELAND Argonauten, Scouting groep de, Erasmuslaan(flat) 0 1217 ST HILVERSUM Argonauten, Scoutinggroep de, Zeverijnstraat 0 HILVERUM Argus Korfbalvereniging, Papelaan 151 1382 RL WEESP Ark, OBS de, Salland 2 1274 KL HUIZEN AT Scholen Laar en Berg, Langsakker 4 1251 GB LAREN Augustinusschool, Kloosterlaan 11 1216 NH HILVERSUM B.M.O.L. Muziekvereniging, Kwakel 41 1241LD KORTENHOEF Bavinckschool, Bosdrift 21 1214 JS HILVERSUM Beatrix Drum & Bugleband, Neuweg 357 1215 JA HILVERSUM BHC, Voormeulenweg 24c 1402 TL BUSSUM Bijvank School, Levensboom 212 1261 MX BLARICUM Binckhorst - St Jan de, Eemnesserweg 17 1251 NA LAREN Blaricumse Voetbalvereniging (BVV), Schapendrift 1c 1261 HK BLARICUM Boomberg, Zorgcentrum, Vondellaan 0 HILVERSUM Brede School Kors Breijerschool, Papelaan 122a 1382 RP WEESP BZC. 2013, Jagerspaadje 30 1231 KJ LOOSDRECHT Calsschool, Minister, J.W. Frisolaan 33 109 1412 AG NAARDEN Calsschool, Minister, Verlengde Fortlaan 43 1412 CW NAARDEN Casaprus College, Prinses Irenelaan 8 1381 NA WEESP Catamaranschool, Bleekveld 1 1231 PR LOOSDRECHT Centraal Wonen Hilversumse Meent, Wandelmeent 52 1218 CP HILVERSUM Christelijke Brede Basisschool Avonturijn (v.h Kruispunt), Eemnesserweg 47 1221 CV HILVERSUM Comeniuscollege - (loc.Bisonlaan, Hilversum), Bisonlaan 1 1217 GH HILVERSUM Comeniusschool - (loc.C. -

Saskatchewan Water Governance Assessment Final Report

Saskatchewan Water Governance Assessment Final Report Unit 1E Institutional Adaptation to Climate Change Project H. Diaz, M. Hurlbert, J. Warren and D. R. Corkal October 2009 1 Table of Contents Abbreviations ………………………………………………………. 3 I Introduction ………………………………………………………… 5 II Methodology .……………………………………………………….. 5 III Integrative Discussion ……………………………………………… 9 IV Conclusions .………………………………………………………… 54 V References ………………………………………………………….. 60 VI Appendices …………………………………………………………. Appendix 1 - Organizational Overviews ..………………………… 62 Introduction ……………………………………………………… 62 Saskatchewan Watershed Authority ...……..………………….… 63 Saskatchewan Ministry for Environment …..………………….… 76 Saskatchewan Ministry for Agriculture .………………………… 85 SaskWater …………………………………….…………………. 94 Prairie Farm Rehabilitation Administration……………………… 103 Appendix 2 - Interview Summaries ……………………….……… 115 Saskatchewan Watershed Authority ……………………….……. 116 Saskatchewan Ministry for Environment ….…………………….. 154 Saskatchewan Ministry for Agriculture .…………………….…… 182 SaskWater ………………………………………………….……. 194 Prairie Farm Rehabilitation Administration …………………….. 210 Irrigation Proponents ……………………………………………. 239 Watershed Advisory Groups ……………………………………. 258 Environment Canada …………………………………………….. 291 SRC ..…………………………………………………………… 298 PPWB …………………………………………………………… 305 Focus Group …………………………………………………….. 308 Appendix 3 - Field Work Guide …………………………………. 318 2 Abbreviations AAFC – Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada ADD Boards – Agriculture Development and Diversification Boards AEGP - Agri-Environmental -

Tussen Vecht En Eem Nasfflen & Comenius

TVE 25e jrg. nr. 4, december 2007 Tussen Vecht en Eem schrift voor regionale geschiedenis M i V ; ' i & " ' t k i M m, 1 ■ l^ÉT tilTW fiSM Ë ® • I « — ' grj lip f e ' V - - pz*!?:-.. - 1 R lo L la n tL 11* - I Nasfflen & Comenius POLDERBEELDEN de Eempolder in beeld POLDERBEELDEN en poëzie de Kcmpolder in beeld en poëzie Een kalender met prachtige foto's van de larense fotograaf Nico Bierlaagh aangevuld met gedichten van de Eemnesser Tseard Veenstra. Beiden geïnspireerd door de Eempolder. De kalender is er in twee fotografie Nico Bierlaagh KALENDER gedichten Tseard Veenstra uitvoeringen. Als wandkalender en als bureaukalender Wandkalender Formaat: 34 x 48 cm Prijs: € 19.95 inch BTW m Uitgeverij VanWijland BV Bureaukalender Formaat 21 x 15 cm Te koop bij Kantoorboekhandel Appelboom of via Prijs: € 9.95 inch BTW www.uitgeverijvanwijland.nl Westland Verzekeringen Makelaars in Assurantiën Hypotheken Verzekeringen Pensioenen Golfstroom 18 • 1271 CP Huizen • Postbus 38 • 1270 AA Huizen Telefoon 035 52 61 370 • Fax 035-5240384 [email protected] • www.westland-verzekeringen.nl TVE 25e jrg. nr. 4, december 2007 Tussen Vecht en Eem Tijdschrift voor regionale geschiedenis mZÈ*M m m "O | * i ij 0 f-mv' m m ïé^fim/fEk .1'. *■•&*•** Het motto van Comenius: ‘Omnia sponte fluant, absit violentia rebus' 'Alles vloeit vanzelf, geweld is niet nodig' (uit Opera didactica omnia,). Uitgegeven door de Stichting Tussen Vecht en Eem Inhoud Dr. P. Rehwinkel, Frans Muthert burgemeester van Naarden Column - Jan Amos draait zich vast Woord vooraf 243 -

1 Lake Diefenbaker Reservoir Operating Plan Consultation

Lake Diefenbaker Reservoir Operating Plan Consultation Downstream Municipalities Meeting July 16, 2012, Park Town Hotel, Saskatoon Recorders: Robin Tod, Heather Davies Facilitator: Dazawray Landrie-Parker Stakeholders: Name Stakeholder Municipality Ben Boots Buffalo Pound Water Treatment Plant Paul Van Pul Hydraulic Archaeology James Harvey Pike Lake Rick Petrie RM of Canaan #225 Mel Henry RM of Corman Park Randy Ridgewell RM of Fertile Valley Eugene Matwishyn RM of Prince Albert Harvey Pippin RM of Vanscoy Brenda Wallace Saskatoon Galen Heinrichs Saskatoon Twyla Yoss Saskatoon Spencer Early Valley People Association Warren Rutherford Warman Russ McPherson Waterwolf Planning Commission William Lemisko Worldaway Farm Meeting Notes 10:00 am - Dazawray opened the meeting and asked the participants to introduce themselves. Dazawray went through an outline of the agenda. She ensured the stakeholders knew that the primary objective of the response session was to provide stakeholders the opportunity to share and discuss issues they perceive as relevant to the renewal of the Lake Diefenbaker Reservoir Operating Plan. Dazawray also reminded stakeholders to finish and send in their completed questionnaire to Robin Tod. The first part of the meeting was to discuss some of the challenges the downstream municipal stakeholders had related to the operation of Gardiner Dam. Challenges There was some concern that an audio recording of John Pomeroy’s presentation was not posted on the website. 1 Dam Safety o Concern was raised as to whether the Authority is collecting adequate data to ensure that Gardiner dam is safe. There was scepticism by participants that the Authority was providing accurate information when it came to the safety of Gardiner and other dams in the province.