Urban Planning and Policy Development Program

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1960 National Gold Medal Exhibition of the Building Arts

EtSm „ NA 2340 A7 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from LYRASIS Members and Sloan Foundation http://archive.org/details/nationalgoldOOarch The Architectural League of Yew York 1960 National Gold Medal Exhibition of the Building Arts ichievement in the Building Arts : sponsored by: The Architectural League of New York in collaboration with: The American Craftsmen's Council held at: The Museum of Contemporary Crafts 29 West 53rd Street, New York 19, N.Y. February 25 through May 15, i960 circulated by The American Federation of Arts September i960 through September 1962 © iy6o by The Architectural League of New York. Printed by Clarke & Way, Inc., in New York. The Architectural League of New York, a national organization, was founded in 1881 "to quicken and encourage the development of the art of architecture, the arts and crafts, and to unite in fellowship the practitioners of these arts and crafts, to the end that ever-improving leadership may be developed for the nation's service." Since then it has held sixtv notable National Gold Medal Exhibitions that have symbolized achievement in the building arts. The creative work of designers throughout the country has been shown and the high qual- ity of their work, together with the unique character of The League's membership, composed of architects, engineers, muralists, sculptors, landscape architects, interior designers, craftsmen and other practi- tioners of the building arts, have made these exhibitions events of outstanding importance. The League is privileged to collaborate on The i960 National Gold Medal Exhibition of The Building Arts with The American Crafts- men's Council, the only non-profit national organization working for the benefit of the handcrafts through exhibitions, conferences, pro- duction and marketing, education and research, publications and information services. -

An Eye on New York Architecture

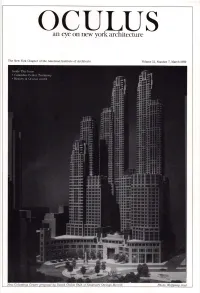

OCULUS an eye on new york architecture The New York Chapter of the American Institute of Architects Volume 51, Number 7, March 1989 ew Co lumbus Center proposal by David Childs FAIA of Skidmore Owings Merrill. 2 YC/AIA OC LUS OCULUS COMING CHAPTER EVENTS Volume 51, Number 7, March 1989 Oculus Tuesday, March 7. The Associates Tuesday, March 21 is Architects Lobby Acting Editor: Marian Page Committee is sponsoring a discussion on Day in Albany. The Chapter is providing Art Director: Abigail Sturges Typesetting: Steintype, Inc. Gordan Matta-Clark Trained as an bus service, which will leave the Urban Printer: The Nugent Organization architect, son of the surrealist Matta, Center at 7 am. To reserve a seat: Photographer: Stan Ri es Matta-Clark was at the center of the 838-9670. avant-garde at the end of the '60s and The New York Chapter of the American Institute of Architects into the '70s. Art Historian Robert Tuesday, March 28. The Chapter is 457 Madison Avenue Pincus-Witten will be moderator of the co-sponsoring with the Italian Marble New York , New York 10022 evening. 6 pm. The Urban Center. Center a seminar on "Stone for Building 212-838-9670 838-9670. Exteriors: Designing, Specifying and Executive Committee 1988-89 Installing." 5:30-7:30 pm. The Urban Martin D. Raab FAIA, President Tuesday, March 14. The Art and Center. 838-9670. Denis G. Kuhn AIA, First Vice President Architecture and the Architects in David Castro-Blanco FAIA, Vice President Education Committees are co Tuesday, March 28. The Professional Douglas Korves AIA, Vice President Stephen P. -

The Social and Political Thought of Paul Goodman

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 1980 The aesthetic community : the social and political thought of Paul Goodman. Willard Francis Petry University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses Petry, Willard Francis, "The aesthetic community : the social and political thought of Paul Goodman." (1980). Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014. 2525. https://doi.org/10.7275/9zjp-s422 This thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DATE DUE UNIV. OF MASSACHUSETTS/AMHERST LIBRARY LD 3234 N268 1980 P4988 THE AESTHETIC COMMUNITY: THE SOCIAL AND POLITICAL THOUGHT OF PAUL GOODMAN A Thesis Presented By WILLARD FRANCIS PETRY Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS February 1980 Political Science THE AESTHETIC COMMUNITY: THE SOCIAL AND POLITICAL THOUGHT OF PAUL GOODMAN A Thesis Presented By WILLARD FRANCIS PETRY Approved as to style and content by: Dean Albertson, Member Glen Gordon, Department Head Political Science n Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2016 https://archive.Org/details/ag:ptheticcommuni00petr . The repressed unused natures then tend to return as Images of the Golden Age, or Paradise, or as theories of the Happy Primitive. We can see how great poets, like Homer and Shakespeare, devoted themselves to glorifying the virtues of the previous era, as if it were their chief function to keep people from forgetting what it used to be to be a man. -

Jewish Dimensions in Modern Visual Culture: Antisemitism, Assimilation, Affirmation

Fairfield University DigitalCommons@Fairfield History Faculty Book Gallery History Department 2009 Jewish Dimensions in Modern Visual Culture: Antisemitism, Assimilation, Affirmation Rose-Carol Washton Long Matthew Baigell Milly Heyd Gavriel D. Rosenfeld Fairfield University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fairfield.edu/history-books Copyright 2009 Brandeis University Press Content archived her with permission from the copyright holder. Recommended Citation Washton Long, Rose-Carol; Baigell, Matthew; Heyd, Milly; and Rosenfeld, Gavriel D., "Jewish Dimensions in Modern Visual Culture: Antisemitism, Assimilation, Affirmation" (2009). History Faculty Book Gallery. 14. https://digitalcommons.fairfield.edu/history-books/14 This item has been accepted for inclusion in DigitalCommons@Fairfield by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Fairfield. It is brought to you by DigitalCommons@Fairfield with permission from the rights- holder(s) and is protected by copyright and/or related rights. You are free to use this item in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses, you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 12 Gavriel D. Rosenfeld Postwar Jewish Architecture and the Memory of the Holocaust When Daniel Libeskind was named in early 2003 as the mas- ter planner in charge of redeveloping the former World Trade Center site in lower Manhattan, most observers saw it as a personal triumph that tes- tifi ed to his newfound status as one of the world’s most respected architects. -

AMERICAN MEMORIAL to SIX MILLION JEWS of EUROPE,Me

AMERICAN MEMORIAL TO SIX MILLION JEWS OF EUROPEme, . 165 WEST 46th STREET Suite 814 NEW YORK 19, N. Y. - Tel. PLaza 7-8430 Circle 6-2880 HONORARY SPONSORS COMMITTEE: BOARD OF DIRECTORS ADVISORY DESIGN COMMITTEE: Honorary Chairman Honorary Chairman CHARLES NAGEL, JR. HON. WILLIAM O'DWYER HON. HUGO E. ROGERS Director, Brooklyn Museum of Art and Sciences Mayor, The City of New York President, Borough of Manhattan Chairman GEOFFREY PARSONS HON. ROBERT MOSES, Member ex-officio I. ROGOSIN Editor, New York Herald Tribune Committee and Board Members: Secretary REV. DR. D. de SOLA POOL Rev. Carlyle Adams PROF. JAMES H. SHELDON FRANCIS HENRY TAYLOR Rabbi Isaac Alcalay Director, Metropolitan Museum of Art Congressman Walter G. Andrews Administrative Chairman Murray Antkies A. R. LERNER Joseph R. Apfel Hon. Thurman Arnold Sholem Asch Rev. Henry A. Atkinson Hon. Joseph C. Baldwin Prof. Salo W. Baron Hon. John J. Bennett B. Bialostotsky February 2, 1950 Justice Hugo L. Black Joseph G. Blum Gay H. Brown Hon. James A. Burke Congressman William T. Byrne Rudolph Callman The Rev. Dr. D. de Sola i^ool Eddie Cantor Hon. John Cashmore 99 Central Park West Congressman Emanuel Celler Prof. Emanuel Chapman New York 23, N. Harry Woodburn Chase Alexander P. Chopin Stuart Constable Hon. Edward Corsi My dear Dr. de Sola Pool: Myer Dorfman Justice William O. Douglas Congressman Edward J. Elsaesser Mrs. Moses P. Epstein In reply to your letter of January 31st, I wi3h Rev. Frederick L. Fagley Hon. James A. Farley to inform you that Mr. Joseph Ho veil was never asked to Abraham Feinberg Rabbi Abraham J. -

Banning Cars from Manhattan

Paul and Percival Goodman Banning Cars from Manhattan 1961 The Anarchist Library Contents Peripheral Parking.......................... 4 Roads.................................. 4 Means, etc................................ 6 Conclusion............................... 6 2 We propose banning private cars from Manhattan Island. Permitted mo- tor vehicles would be buses, small taxis, vehicles for essential services (doctor, police, sanitation, vans, etc.), and the trucking used in light industry. Present congestion and parking are unworkable, and other proposed solu- tions are uneconomic, disruptive, unhealthy, nonurban, or impractical. It is hardly necessary to prove that the actual situation is intolerable. “Motor trucks average less than six miles per hour in traffic, as against eleven miles per hour for horse drawn vehicles in 1911.” “During the ban on nonessential vehicles during the heavy snowstorm of February 1961, air pollution dropped 66 per cent.” (New York Times, March 13, 1961.) The street widths of Manhattan were designed, in 1811, for buildings of one to four stories. By banning private cars and reducing traffic, we can, in most areas, close off nearly nine out of ten cross-town streets and every second north-south avenue. These closed roads plus the space now used for off-street parking will give us a handsome fund of land for neighborhood relocation. At present over 35 percent of the area of Manhattan is occupied by roads. Instead of the present grid, we can aim at various kinds of enclosed neighborhoods, in approximately 1200-foot to 1600-foot superblocks. It would be convenient, however, to leave the existing street pattern in the main midtown shopping and business areas, in the financial district, and wherever the access for trucks and service cars is imperative. -

The Museum of Modern Art for RELEASE: Thursday, October I7, I968 11 West 53 Street, New York, N.Y

^^. The Museum of Modern Art FOR RELEASE: Thursday, October I7, I968 11 West 53 Street, New York, N.Y. 10019 Tel. 245-3200 Cable: Modernart PRESS PREVIEW: Wednesday, October I6, I968 2-6 P.M. A six-foot scale model of Louis Kahn^s Monument to the Six Million Jewish Martyrs will have its first public showing at The Museum of Modern Art from October I7 through November I5. Commissioned by the Committee to Commemorate the Six Million Jewish Martyrs representing nearly 50 national and local Jewish organizations, the monument was designed for a site in Battery Park, alongside the Promenade near the Emma Lazarus Tablet and overlooking the Statue of Liberty. It has been approved in principle by the Parks Department and by the City Art Commission, and it is hoped that work can be completed by 1970. Arthur Drexler, Director of the Museum*s Department of Architecture and Design, says that the monument offers a physical embodiment of hope as well as despair. It consists of seven glass piers each 10* square and 11* high placed on a 66^ square granite pedestal. The center pier has been given the character of a small chapel into which people may enter. The walls of the chapel will be inscribed. The six piers around the center, all of equal dimensions^ are blank. "The one - the chapel - speaks; the other six are silent," the architect says. The piers are constructed of solid blocks of glass that interlock without the use of mortar, "Changes of light, the seasons of the year, the play of the weather, and the drama of movement on the river will transmit their life to the monument," Mr. -

June 2020 Landmarks Minutes

Alida Camp 505 Park Avenue, Suite 620 Chair New York, NY 10022 (212) 758-4340 Will Brightbill (212) 758-4616 (Fax) District Manager [email protected] – E-Mail www.cb8m.com – Website The City of New York Community Board 8 Manhattan Landmarks Committee Monday, May 18, 2020 – 6:30PM Please note: The resolutions contained in the committee minutes are recommendations submitted by the committee chair to the Community Board. At the monthly full board meeting, the resolutions are discussed and voted upon by all members of Community Board 8 Manhattan. PLEASE NOTE: When evaluating Applications for Certificates of Appropriateness, the Landmarks Committee of Community Board 8M ONLY considers the appropriateness of the proposal to the architecture of the building and, in the case of a building within an Historic District, the appropriateness of the proposal to the character of that Historic District. All testimony should be related to such appropriateness. The Committee recommends a Resolution to the full Community Board, which votes on a Resolution to be sent to the Landmarks Preservation Commission. These Resolutions are advisory; the decision of the Landmarks Preservation Commission is binding. Applicants and members of the public who are interested in the issues addressed are invited, but not required, to attend the Full Board meeting on Wednesday, June 17, 2020 via Zoom at 6:30PM. They may testify for up to three minutes in the Public Session, which they must sign up for no later than 6:45PM. Members of the Board will discuss the items in executive session; if a member of the public wishes a comment made or a question asked at this time, he or she must ask a Board Member to do it. -

Robert Fishman Curriculum Vitae Page 1 Professor of Architecture and Urban Planning the Taubman College of Architecture and Urba

Robert Fishman Curriculum vitae Page 1 Professor of Architecture and Urban Planning The Taubman College of Architecture and Urban Planning The University of Michigan 2000 Bonisteel Boulevard Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109-2069; 734 764-6885; fax: 734 763-2322; [email protected] . Education: Ph.D. Harvard University, 1974. History. A.M. Harvard University, 1969. History. A.B. Stanford University, 1968. History. Employment: Professor of Architecture and Urban Planning, The Taubman College of Architecture and Urban Planning, The University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, 2000- Emil Lorch Professor, 2006-2009. Professor of History, Faculty of Arts and Sciences, Rutgers University, Camden. 1988-2000; (Associate Professor with tenure, 1978-88; Assistant Professor, 1974-78). Adjunct Visiting Professor, Department of Urban Studies and Planning, Hunter College, City University of New York, Fall 1998. Adjunct Visiting Professor of History and Urban Studies, University of Pennsylvania, 1990-92. Visiting Associate Professor, Urban Studies, Barnard College, Columbia University, Fall 1984. Honors Laurence Gerckens Prize for Lifetime Achievement in Scholarship and Teaching, 2009. Society for American City and Regional Planning History. Shared with Eugenie Birch, U. of Pennsylvania. Distinguished Visiting Scholar, Cornell University College of Architecture and Planning, 2007. Associate Editor, Journal of the American Planning Association, 2005-2008. Member, Editorial Board, 2008- President, The Urban History Association, 2003. The Urban Studies Lectureship, The University of Pennsylvania, 2002. Robert Fishman Curriculum vitae Page 2 The Lansdowne Lectureship, The University of Victoria, British Columbia, 2002. Board, The Society for City and Regional Planning History, 1999-2003. Public Policy Scholar, Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, 1999. Cass Gilbert Visiting Professor, School of Architecture, University of Minnesota, March, 1998. -

THE WORLD of PAUL GOODMAN Anarchy 11

THE WORLD OF PAUL GOODMAN Reviews of COMMUNITAS, UTOPIAN ESSAYS and GROWING UP ABSURD Paul Goodman THE CHILDREN AND PSYCHOLOGY Harold Drasdo THE CHARACTER BUILDERS A% S. Neill SUMMERHILL vs. STANDARD EDUCATION Ana$&'( 1) A JOURNAL OF ANARCHIST IDEAS 1s 6d or 25 cents inside front cover Con.ents of No%)) *an!a$( )/+, The World of Paul Goodman John Ellerby 1 Communitas Revisited 3 Youth and Absurdity 14 Practical Proposals 17 The Children and Psychology Paul Goodman 20 The Character Builders Harold Drasdo 25 Summerhill Education vs. Standard Education A. S. Neill 29 Cover: Bibliography for the New Commune (from Communitas) O.'e$ iss!es of ANARCHY: No.1. Alex Comfort on Sex-and-Violence, Nicolas Walter on the New Wave, and articles on education, opportunity, and Galbraith. No.2. A symposium on Workers' Control. No.3. What does anarchism mean today?, and articles on Africa, the 'Long Revolution' and exceptional children. No.4. George Molnar on conflicting strains in anarchism, Colin Ward on the breakdown of institutions. No.5. A symposium on the Spanish Revolution of 1936. No.6. Anarchy and Cinema: articles on Vigo, Buñuel and Flaherty. Two experimental film-makers discuss their work. No.7. A symposium on Adventure Playgrounds. No.8. Anarchists and Fabians, Kenneth Maddock on action anthropology, Reg Wright on erosion inside capitalism, Nicolas Walter on Orwell. No.9. A symposium on Prison. No.10. Alan Sillitoe's Key to the Door, Colin MacInnes on crime, Augustus John on utopia, Committee of 100 seminar on industry and workers' control. Subscribe to ANARCHY single copies 1s. -

Messenger Sivan-Tammuz-Av 5779

Volume 160 Number 11 The Temple of Loving - Kindness July-August 2019 Messenger Sivan-Tammuz-Av 5779 Temple Hesed, 1 Knox Road, Scranton, PA 18505 Annual Meeting renews Rabbi’s Contract for 1 year Rabbi Daniel Swartz has agreed to a Steve Seitchik and Esther Adelman will one-year contract so the Temple can remain co-presidents for the upcoming make plans for the building and howdecide to year. handlehow to handleits deficit. its deficit. A portion of the building fund will be used to clear The other officers are: The congregation will also sell off an 1st Vice President, Cheryl Friedman; this year’s deficit. unused portions of its cemetery to the 2nd Vice President, Larry Milliken; Special points of interest: DunmoreThe congregation Cemetery will Association also sell off and an use Treasurer, Jeffrey Leventhal; Secretary, • Yiddish classes aunused portion portion of the ofbuilding its cemetery fund to to clear the Jennifer Novak; Assistant Secretary, thisDunmore year’s Cemetery deficit. Association with the Joan Davis. money going to the Cemetery Fund to • Davidow memorial The deficit comes with the loss of the Board members: Start Date Expiration pay for perpetual care. NativityMiguel school which rented the of Term • Walls Chanting Circle lowerThe deficit level comesclassrooms. from theHeinerfeld loss of theReal EstateNativityMiguel has been school hired which to find rented a tenant the Natalie Gelb 9/1/17—8/31/20 • Back-to-School backpacks Paula Kane 9/1/17—8/31/20 forlower the level now classrooms.-vacant space. Hinerfeld Com- mercial Real Estate has been hired to Carol Leventhal 9/1/18—8/31/20 Mark Davis will head the long-range Judith Golden 9/1/18—8/31/21 find a tenant for the now-vacant space. -

BATTLING for BROOKLYN HEIGHTS by Martin L

1 BATTLING FOR BROOKLYN HEIGHTS by Martin L. Schneider Introduction Anthony C. Wood Preservation in New York City has achieved such a level of success that it risks being taken for granted by new generations of New Yorkers; a fate that could translate into a future of unnecessarily lost buildings and disfigured historic neighborhoods. December 2009 saw the designation of the city’s 100th historic district and 2010 marks the 45th anniversary of the passage of New York City’s hard won landmarks law. Preservation in New York certainly has come of age. Contributing to the possibility that future New Yorkers may misguidedly assume preservation is now the city’s default policy position (tragically ignoring the cold reality that the blood of most New York powerbrokers still races at the mere mention of real estate development) is the fact that preservationists have largely failed to tell their stories of the often heroic efforts required to save the city’s landmarks and historic districts. One wonderful exception to this is the story of the saving of Brooklyn Heights. Thanks to the prescience and dedication of those involved in this battle, the struggle to save Brooklyn Heights is the best documented of all New York City’s preservation sagas. Today we are fortunate to have available to us extensive newspaper accounts from that time, numerous original documents, oral histories and personal remembrances. If only the same could be said for other significant chapters in preservation’s history. Thanks to Martin L. Schneider, we now can add to the existing material on Brooklyn Heights, this compelling narrative “Battling for Brooklyn Heights.” Told through the eyes of a witness to history and capturing the emotions of one who lived through it, Mr.