Urban America: Goals Andm Ro

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1960 National Gold Medal Exhibition of the Building Arts

EtSm „ NA 2340 A7 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from LYRASIS Members and Sloan Foundation http://archive.org/details/nationalgoldOOarch The Architectural League of Yew York 1960 National Gold Medal Exhibition of the Building Arts ichievement in the Building Arts : sponsored by: The Architectural League of New York in collaboration with: The American Craftsmen's Council held at: The Museum of Contemporary Crafts 29 West 53rd Street, New York 19, N.Y. February 25 through May 15, i960 circulated by The American Federation of Arts September i960 through September 1962 © iy6o by The Architectural League of New York. Printed by Clarke & Way, Inc., in New York. The Architectural League of New York, a national organization, was founded in 1881 "to quicken and encourage the development of the art of architecture, the arts and crafts, and to unite in fellowship the practitioners of these arts and crafts, to the end that ever-improving leadership may be developed for the nation's service." Since then it has held sixtv notable National Gold Medal Exhibitions that have symbolized achievement in the building arts. The creative work of designers throughout the country has been shown and the high qual- ity of their work, together with the unique character of The League's membership, composed of architects, engineers, muralists, sculptors, landscape architects, interior designers, craftsmen and other practi- tioners of the building arts, have made these exhibitions events of outstanding importance. The League is privileged to collaborate on The i960 National Gold Medal Exhibition of The Building Arts with The American Crafts- men's Council, the only non-profit national organization working for the benefit of the handcrafts through exhibitions, conferences, pro- duction and marketing, education and research, publications and information services. -

Trinity Tripod, 1960-09-26

Inside Pages •Aisle Say' Goes Editorials Nightcl ubing. No Bottles Trough Windows I *By George' Begins Today, Polices: Interested Page 4. - drinify or Curious? Voi. LVUV, TRINITY COLLEGE, HARTFORD, CONN. MONDAY, SEPTEMBER 26, I960 Tabled Curriculum Revisions Dick, Cabot Victorious Face Oct. 15 Trustees Verdict Vernon St. Takes 135; SEPT. 22—The new curric-, the Trustees consider approv- ulum which last year was! ing - the curriculum at their Student Body Gives passed by the faculty and next meeting, Oct. 15. 23 Pledge Grow While tabled temporarily by the .Constuction on the North jTrrustees has not "been aban-1 Campus, a dormitory building jdoned, President Jacobs said i between Allen Place and Ver- GOP 371-142 Mandate i today. i non Street, will begin "as 5 Join D. Phi Splinter | He said only a few points! early this fall as possible," Dr. SEPT. 22—K the Trinity, i remain to be studied before J Jacobs said. College student body was aj1. Which candidate do vou favor for President? Vernon Street's Annual quest Fraternity Ruling- for now blood end or! last week political weathervane, tihe wor- j KENNEDY 142 NIXON 371 UNDECIDED 48. The struct urt will house Glum Spectators ries of Richard Nixon and his | 2. Which candidate will your parents most likely wild 136 students pledged Profs' Smut Pics some fraternity and unalfili- from 200 eligible. campaign staff would'be over. favor? j ated students who wish to be An overwhelming majority The three-week-old "Q.K.D," KENNEDY 103 NIXON 210 DON'T KNOW 104 Prompt Smith Wit ; assigned there. -

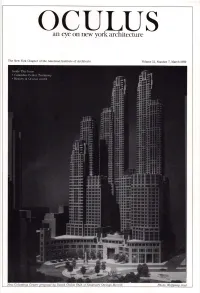

An Eye on New York Architecture

OCULUS an eye on new york architecture The New York Chapter of the American Institute of Architects Volume 51, Number 7, March 1989 ew Co lumbus Center proposal by David Childs FAIA of Skidmore Owings Merrill. 2 YC/AIA OC LUS OCULUS COMING CHAPTER EVENTS Volume 51, Number 7, March 1989 Oculus Tuesday, March 7. The Associates Tuesday, March 21 is Architects Lobby Acting Editor: Marian Page Committee is sponsoring a discussion on Day in Albany. The Chapter is providing Art Director: Abigail Sturges Typesetting: Steintype, Inc. Gordan Matta-Clark Trained as an bus service, which will leave the Urban Printer: The Nugent Organization architect, son of the surrealist Matta, Center at 7 am. To reserve a seat: Photographer: Stan Ri es Matta-Clark was at the center of the 838-9670. avant-garde at the end of the '60s and The New York Chapter of the American Institute of Architects into the '70s. Art Historian Robert Tuesday, March 28. The Chapter is 457 Madison Avenue Pincus-Witten will be moderator of the co-sponsoring with the Italian Marble New York , New York 10022 evening. 6 pm. The Urban Center. Center a seminar on "Stone for Building 212-838-9670 838-9670. Exteriors: Designing, Specifying and Executive Committee 1988-89 Installing." 5:30-7:30 pm. The Urban Martin D. Raab FAIA, President Tuesday, March 14. The Art and Center. 838-9670. Denis G. Kuhn AIA, First Vice President Architecture and the Architects in David Castro-Blanco FAIA, Vice President Education Committees are co Tuesday, March 28. The Professional Douglas Korves AIA, Vice President Stephen P. -

The Social and Political Thought of Paul Goodman

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 1980 The aesthetic community : the social and political thought of Paul Goodman. Willard Francis Petry University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses Petry, Willard Francis, "The aesthetic community : the social and political thought of Paul Goodman." (1980). Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014. 2525. https://doi.org/10.7275/9zjp-s422 This thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DATE DUE UNIV. OF MASSACHUSETTS/AMHERST LIBRARY LD 3234 N268 1980 P4988 THE AESTHETIC COMMUNITY: THE SOCIAL AND POLITICAL THOUGHT OF PAUL GOODMAN A Thesis Presented By WILLARD FRANCIS PETRY Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS February 1980 Political Science THE AESTHETIC COMMUNITY: THE SOCIAL AND POLITICAL THOUGHT OF PAUL GOODMAN A Thesis Presented By WILLARD FRANCIS PETRY Approved as to style and content by: Dean Albertson, Member Glen Gordon, Department Head Political Science n Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2016 https://archive.Org/details/ag:ptheticcommuni00petr . The repressed unused natures then tend to return as Images of the Golden Age, or Paradise, or as theories of the Happy Primitive. We can see how great poets, like Homer and Shakespeare, devoted themselves to glorifying the virtues of the previous era, as if it were their chief function to keep people from forgetting what it used to be to be a man. -

Nixon Announces Cease-Fire

Nixon announces cease-fire; settlement effective Saturday by Mark Fisher on nationwide TV and radio, reading a withdrawn from Indochina within 60 The full text of the agreement, as well as President Richard M. Nixon statement he said was being days of the date of the cease-fire, the the protocols to carry it out, will be announced last night that an agreement simultaneously issued by the North President said. issued today, he said. has been reached with North Vietnam to Vietnamese. Nixon said the agreement, which was Nixon said his decision not to discuss end the Vietnam War. The agreement "meets the goals and initialed yesterday by Henry Kissinger the progress of the recent negotiations Nixon said the agreement included has the full support of President Nguyen and Hanoi negotiator Le Due Tho, met was based on a desire not to jeopardize provisions for a cease-fire beginning 7 Van Thieu and the government of South all the conditions he had laid down for a the progress of the peace talks. p.m. Saturday EST and for release of all Vietnam," Nixon said. He said the cease-fire in his speech last May 8. The "The important thing was not to talk U.S. prisoners of war within 60 days agreement recognizes the Thieu agreement will be formally signed about peace but to get peace," he said. from the time the cease-fire takes effect. government as the "sole legitimate Saturday. "This we have done." He said the agreement would "end government of South Vietnam" and that Nixon's address followed As Nixon was speaking, Thieu the war and bring peace with honor in the United States will continue to give consultations held earlier with his announced the agreement in South Southeast Asia." South Vietnam military aid. -

Agnew Announces Resignation

(tanrrttrul latin GlamjmB Serving Storrs Since 1896 VOL. LXXI NO. 24 STORRS.CONN. THURSDAY, OCTOBER 11, 1973 5 CENTS OFF CAMPUS Agnew announces resignation Israel launches raids behind Arab lines Premier Meir Agnew pleads warns Jordan no contest to avoid war to tax evasion (UPI) - Prime Minister Golda Men- By DEB NO YD said Wednesday night Israeli forces have Spiro T. Agnew, S9th Vice President pushed the Syrians off the Golan of the United States, announced his Heights and are driving back Egyptian resignation 2 p.m. yesterday. President troops holding the East Bank of the Richard M. Nixon was informed of Suez Canal. Jordan's King Hussein called Agnew's decision 6 p.m. Tuesday and up reserve troops but Mrs. Meir advised met with members of the House and him to stay out of the war. Senate Wednesday night. A communique issued in Damascus Agnew spent most of the day in the said, however, that heavy fighting Executive Office Building adjacent to the White House and called in his staff continued along the frontier. "Our forces on the frontlines foiled in the early afternoon to inform them of all enemy attempts and inflicted on it his decision. Previous to his announcement of heavy losses in personnel and equipment resignation, Agnew pleaded no contest and prevent it from any success," the to a charge of evading income taxes in statement said. 1967 in U.S. District Court in Baltimore Mrs. Meir spoke in a televised in a court proceeding that took 36 address to the nation after a day that minutes. -

Jewish Dimensions in Modern Visual Culture: Antisemitism, Assimilation, Affirmation

Fairfield University DigitalCommons@Fairfield History Faculty Book Gallery History Department 2009 Jewish Dimensions in Modern Visual Culture: Antisemitism, Assimilation, Affirmation Rose-Carol Washton Long Matthew Baigell Milly Heyd Gavriel D. Rosenfeld Fairfield University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fairfield.edu/history-books Copyright 2009 Brandeis University Press Content archived her with permission from the copyright holder. Recommended Citation Washton Long, Rose-Carol; Baigell, Matthew; Heyd, Milly; and Rosenfeld, Gavriel D., "Jewish Dimensions in Modern Visual Culture: Antisemitism, Assimilation, Affirmation" (2009). History Faculty Book Gallery. 14. https://digitalcommons.fairfield.edu/history-books/14 This item has been accepted for inclusion in DigitalCommons@Fairfield by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Fairfield. It is brought to you by DigitalCommons@Fairfield with permission from the rights- holder(s) and is protected by copyright and/or related rights. You are free to use this item in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses, you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 12 Gavriel D. Rosenfeld Postwar Jewish Architecture and the Memory of the Holocaust When Daniel Libeskind was named in early 2003 as the mas- ter planner in charge of redeveloping the former World Trade Center site in lower Manhattan, most observers saw it as a personal triumph that tes- tifi ed to his newfound status as one of the world’s most respected architects. -

01Connectorjul

The CONNector - JULY 2001 JULY 2001 Volume 3 Number 3 IN THIS ISSUE The State Librarian's Column The State Librarian s reflects upon the vast network of close collaboration between the State Library and all segments of the library community. State Library Board Notes Significant activities of the State Library Board as per the May 21, 2001 meeting. Governor's Service Awards - July 2000 - July, 2001 Congratulations to four of our CSL employees for excellent service. CSL Affirmative Action Plan 2001 The State Commission on Human Rights and Opportunities (CHRO) gave approval of the 2001 Affirmative Action Plan. A message from Kendall Wiggin to CHRO Director Cynthia Watts Elder confirms our commitment to affirmative action. Employee Recognition Awards for Years of State Service Employees were recognized for their years of state service in Memorial Hall, Museum of Connecticut History on June 11, 2001. Partnerships Eagle Scout Candidate Creates "Sensory Garden" This "Sensory Garden" garden spans the entire front of the library comes alive for people with different disabilities. LBPH is grateful to James Dossot for leading the team to create this wonderful environment for its patrons. History Day Students and the Connecticut State Library Students participating in the 2001 National History Day competition were shown the collections and resources the Connecticut State Library has to offer. Connecticut State Library New Hours The new hours of the Connecticut State Library starting July 28, 2001. Honoring the Past Biographies of Judges & Attorneys Selected biographies, obituaries and remarks of notable judges and attorneys can be found in the original early volumes of the Connecticut Report, including comprehensive information about Noah Webster. -

AMERICAN MEMORIAL to SIX MILLION JEWS of EUROPE,Me

AMERICAN MEMORIAL TO SIX MILLION JEWS OF EUROPEme, . 165 WEST 46th STREET Suite 814 NEW YORK 19, N. Y. - Tel. PLaza 7-8430 Circle 6-2880 HONORARY SPONSORS COMMITTEE: BOARD OF DIRECTORS ADVISORY DESIGN COMMITTEE: Honorary Chairman Honorary Chairman CHARLES NAGEL, JR. HON. WILLIAM O'DWYER HON. HUGO E. ROGERS Director, Brooklyn Museum of Art and Sciences Mayor, The City of New York President, Borough of Manhattan Chairman GEOFFREY PARSONS HON. ROBERT MOSES, Member ex-officio I. ROGOSIN Editor, New York Herald Tribune Committee and Board Members: Secretary REV. DR. D. de SOLA POOL Rev. Carlyle Adams PROF. JAMES H. SHELDON FRANCIS HENRY TAYLOR Rabbi Isaac Alcalay Director, Metropolitan Museum of Art Congressman Walter G. Andrews Administrative Chairman Murray Antkies A. R. LERNER Joseph R. Apfel Hon. Thurman Arnold Sholem Asch Rev. Henry A. Atkinson Hon. Joseph C. Baldwin Prof. Salo W. Baron Hon. John J. Bennett B. Bialostotsky February 2, 1950 Justice Hugo L. Black Joseph G. Blum Gay H. Brown Hon. James A. Burke Congressman William T. Byrne Rudolph Callman The Rev. Dr. D. de Sola i^ool Eddie Cantor Hon. John Cashmore 99 Central Park West Congressman Emanuel Celler Prof. Emanuel Chapman New York 23, N. Harry Woodburn Chase Alexander P. Chopin Stuart Constable Hon. Edward Corsi My dear Dr. de Sola Pool: Myer Dorfman Justice William O. Douglas Congressman Edward J. Elsaesser Mrs. Moses P. Epstein In reply to your letter of January 31st, I wi3h Rev. Frederick L. Fagley Hon. James A. Farley to inform you that Mr. Joseph Ho veil was never asked to Abraham Feinberg Rabbi Abraham J. -

Report for Congress Received Through the CRS Web

Order Code RL31497 Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web Creation of Executive Departments: Highlights from the Legislative History of Modern Precedents Updated July 30, 2002 Thomas P. Carr Analyst in American National Government Government and Finance Division Congressional Research Service ˜ The Library of Congress Creation of Executive Departments: Highlights from the Legislative History of Modern Precedents Summary Congress is now considering proposals to create a Department of Homeland Security. Since World War II, Congress has created or implemented major reorganizations of seven of the now existing 14 Cabinet departments. This report describes the principal elements of legislative process that established the Departments of Defense; Health, Education, and Welfare (HEW) (now, in part, Health and Human Services); Housing and Urban Development; Transportation; Energy; Education; and Veterans Affairs. Congressional consideration of legislation establishing Cabinet departments has generally exhibited certain common procedural elements. In each case, successful congressional action was preceded by a presidential endorsement, the submission of draft legislation, or, in one instance, a reorganization plan by the President. In the Congress in which they were approved, these proposals were considered by the House Committee on Government Operations and the Senate Committee on Governmental Affairs (or their predecessors). The bill creating the Department of Defense (considered by the Senate Armed Services Committee), and the bill creating the Department of Energy (considered in part by the House Post Office and Civil Service Committee), were the two exceptions to this procedure. With the exception of the Defense and Veterans Affairs Departments, all the departmental creation proposals were considered in the House under provisions of an open rule. -

Office of the Public Records Administrator and State Archives

Guide to the Archives in the Connecticut State Library Fourth Edition Office of the Public Records Administrator and State Archives Connecticut State Library Hartford, Connecticut August 1, 2002 COMPILED BY Mark H. Jones, State Archivist Bruce Stark, Assistant State Archivist Nancy Shader, Archivist OFFICE OF THE PUBLIC RECORDS ADMINISTRATOR AND STATE ARCHIVES Eunice G. DiBella, CRM, Public Records Administrator Dr. Mark H. Jones, State Archivist STATE LIBRARY BOARD Ann M. Clark, Chair Dr. Edmund B. Sullivan, Vice-Chair Honorable Joseph P. Flynn Richard D. Harris, Jr. Honorable Francis X. Hennessy Joy Hostage Dr. Mollie Keller Larry Kibner E. Frederick Petersen Dr. Betty Sternberg Edwin E. Williams LIBRARY ADMINISTRATIVE STAFF Kendall F. Wiggin, State Librarian Richard Kingston, Director, Administrative Services Lynne Newell, Director, Division of Information Services Sharon Brettschneider, Director, Division of Library Development Eunice G. DiBella, Public Records Administrator Dean Nelson, Museum Administrator Office of the Public Records Administrator and State Archives Guide to the Archives in the Connecticut State Library Fourth Edition Connecticut State Library Hartford, Connecticut August 1, 2002 FRONT COVER RG 005: Governor Oliver Wolcott, Jr., Incoming Correspondence, Box 4 BACK COVER RG 005, Governor Alexander H. Holley, Incoming Correspondence, Broadside of Resolution, Box 11 i Introduction Since 1855, the Connecticut State Library has acquired archival records documenting the evolution and implementation of state government policies, the rights and claims of its citizens, and the history of its nongovernmental institutions, economy, ethnic and social groups, politics, military history, families and individuals. In 1909, the General Assembly recognized in law the State Library’s unique role by making it the official repository, or State Archives, for state and local public records. -

Danbury Prison Fire: What Happened? What Has Been Done to Prevent Recurrence

REPORT BY THE Comptroller General OF THE UNITED STATES ' The Danbury Prison Fire- What Happened? What Has Been Done To Prevent Recurrence? GAO reconstructs the events of the morning of July 7, 1977, when a fire at the Danbury Federal Correctional Institution in Connect- icut took the lives of five inmates and in- jured many others. The report discusses the fire's origin, the activities of correctional staff and inmates, the factors contributing to the tragedy, and the actions taken by the Bureau of Prisons to investigate the fire and make improvements GGD-78-82 HE~QC~~~~CKOZJF~~~~~ ~AUGUST 4, 1978 COMPTROLLER GENERAL'S REPORT THE DANBURY PRISON FIRE-- TO TOE HONORABLE ABRAHAM WHAT HAPPENED? RIBICOFF AND THE HONCRABLE WHAT HAS BEEN DONE TO LOWELL WEICKER, JR. PREVENT RECURREPNCE? UNITED STATES SENATE DIGEST GAO was asked by Senators Ribicoff and Weicker to investigate the objectivity, accuracy, and completeness of the Bureau of Prisons investigation and report on the July 7, 1977, fire at the Federal Correc- tional Institution in Danbury, Connecticut. The fire killed five inmates and injured many others. The Bureau of Prisons had convened a Board of Inquiry composed of Bureau personnel, none of whom were experts in fire safety investigations. This raised questions re- garding the Bureau's objectivity and ability to effectively investigate the Danbury fire. Subsequently, the Connecticut chapter of the National Association for the Advance- ment of Colored People reported that institu- tional staff members did not adhere to estab- lished policies and procedures during the fire. (See chs. 1 and 5.) GAO found no evidence that the Board of Inquiry was not objective in its investi- gation of the fire.