THE WORLD of PAUL GOODMAN Anarchy 11

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1960 National Gold Medal Exhibition of the Building Arts

EtSm „ NA 2340 A7 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from LYRASIS Members and Sloan Foundation http://archive.org/details/nationalgoldOOarch The Architectural League of Yew York 1960 National Gold Medal Exhibition of the Building Arts ichievement in the Building Arts : sponsored by: The Architectural League of New York in collaboration with: The American Craftsmen's Council held at: The Museum of Contemporary Crafts 29 West 53rd Street, New York 19, N.Y. February 25 through May 15, i960 circulated by The American Federation of Arts September i960 through September 1962 © iy6o by The Architectural League of New York. Printed by Clarke & Way, Inc., in New York. The Architectural League of New York, a national organization, was founded in 1881 "to quicken and encourage the development of the art of architecture, the arts and crafts, and to unite in fellowship the practitioners of these arts and crafts, to the end that ever-improving leadership may be developed for the nation's service." Since then it has held sixtv notable National Gold Medal Exhibitions that have symbolized achievement in the building arts. The creative work of designers throughout the country has been shown and the high qual- ity of their work, together with the unique character of The League's membership, composed of architects, engineers, muralists, sculptors, landscape architects, interior designers, craftsmen and other practi- tioners of the building arts, have made these exhibitions events of outstanding importance. The League is privileged to collaborate on The i960 National Gold Medal Exhibition of The Building Arts with The American Crafts- men's Council, the only non-profit national organization working for the benefit of the handcrafts through exhibitions, conferences, pro- duction and marketing, education and research, publications and information services. -

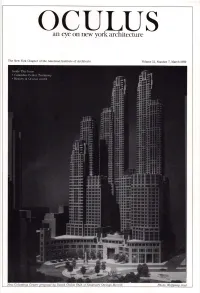

An Eye on New York Architecture

OCULUS an eye on new york architecture The New York Chapter of the American Institute of Architects Volume 51, Number 7, March 1989 ew Co lumbus Center proposal by David Childs FAIA of Skidmore Owings Merrill. 2 YC/AIA OC LUS OCULUS COMING CHAPTER EVENTS Volume 51, Number 7, March 1989 Oculus Tuesday, March 7. The Associates Tuesday, March 21 is Architects Lobby Acting Editor: Marian Page Committee is sponsoring a discussion on Day in Albany. The Chapter is providing Art Director: Abigail Sturges Typesetting: Steintype, Inc. Gordan Matta-Clark Trained as an bus service, which will leave the Urban Printer: The Nugent Organization architect, son of the surrealist Matta, Center at 7 am. To reserve a seat: Photographer: Stan Ri es Matta-Clark was at the center of the 838-9670. avant-garde at the end of the '60s and The New York Chapter of the American Institute of Architects into the '70s. Art Historian Robert Tuesday, March 28. The Chapter is 457 Madison Avenue Pincus-Witten will be moderator of the co-sponsoring with the Italian Marble New York , New York 10022 evening. 6 pm. The Urban Center. Center a seminar on "Stone for Building 212-838-9670 838-9670. Exteriors: Designing, Specifying and Executive Committee 1988-89 Installing." 5:30-7:30 pm. The Urban Martin D. Raab FAIA, President Tuesday, March 14. The Art and Center. 838-9670. Denis G. Kuhn AIA, First Vice President Architecture and the Architects in David Castro-Blanco FAIA, Vice President Education Committees are co Tuesday, March 28. The Professional Douglas Korves AIA, Vice President Stephen P. -

The Counter Culture in American Environmental History Jean

Cercles 22 (2012) NEW BEGINNING: THE COUNTER CULTURE IN AMERICAN ENVIRONMENTAL HISTORY JEAN-DANIEL COLLOMB Université Jean Moulin, Lyon Although it appears to have petered out in the early 1970s, the counter culture of the previous decade modified many aspects of American life beyond recognition. As a matter of fact, there is a wealth of evidence to suggest that its transformative effects are still being felt in American society today. The ideas nurtured by the counter culture have deeply affected the institution of the family, the education system, and the definition of gender roles, to name only the most frequently debated cases. It should come as no surprise, therefore, that American environmentalism was no exception. Indeed, the American environmental movement as it has unfolded since the 1970s bears little resemblance to its earlier version. Up until the 1960s, American environmentalism had been dominated by small-sized, rather exclusive and conservative organizations, like the Sierra Club, whose main focus had been wilderness preservation. By contrast, contemporary American environmentalism has now turned into a mass movement whose membership ranges from old-style nature lovers to radical anti-capitalist activists. Contemporary environmentalists now concern themselves not Just with wilderness preservation but also with quality-of-life issues, the effects of high consumption and of the so-called American way of life, and pollution. Such a shift in style and obJectives begs several important questions: in what way did the counter culture of the 1960s reshape and redefine American environmentalism? More important still, why were the ideas advocated by the counter-culturists so easily integrated into the environmental agenda? Put differently, one may wonder whether the rapprochement between counter-cultural thinking and environmental activism was inevitable. -

Intellectuals In

Intellectuals in The Origins of the New Left and Radical Liberalism, 1945 –1970 KEVIN MATTSON Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Mattson, Kevin, 1966– Intellectuals in action : the origins of the new left and radical liberalism, 1945–1970 / Kevin Mattson. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-271-02148-9 (cloth : alk. paper) — ISBN 0-271-02206-X (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. New Left—United States. 2. Radicalism—United States. 3. Intellectuals— United States—Political activity. 4. United States and government—1945–1989. I. Title. HN90.R3 M368 2002 320.51Ј3Ј092273—dc21 2001055298 Copyright ᭧ 2002 The Pennsylvania State University All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Published by The Pennsylvania State University Press, University Park, PA 16802–1003 It is the policy of The Pennsylvania State University Press to use acid-free paper for the first printing of all clothbound books. Publications on uncoated stock satisfy the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992. For Vicky—and making a family together In my own thinking and writing I have deliberately allowed certain implicit values which I hold to remain, because even though they are quite unrealizable in the immediate future, they still seem to me worth displaying. One just has to wait, as others before one have, while remembering that what in one decade is utopian may in the next be implementable. —C. Wright Mills, “Commentary on Our Country, Our Culture,” 1952 Contents Acknowledgments ix Introduction: Why Go Back? 1 1 A Preface to the politics of Intellectual Life in Postwar America: The Possibility of New Left Beginnings 23 2 The Godfather, C. -

The Social and Political Thought of Paul Goodman

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 1980 The aesthetic community : the social and political thought of Paul Goodman. Willard Francis Petry University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses Petry, Willard Francis, "The aesthetic community : the social and political thought of Paul Goodman." (1980). Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014. 2525. https://doi.org/10.7275/9zjp-s422 This thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DATE DUE UNIV. OF MASSACHUSETTS/AMHERST LIBRARY LD 3234 N268 1980 P4988 THE AESTHETIC COMMUNITY: THE SOCIAL AND POLITICAL THOUGHT OF PAUL GOODMAN A Thesis Presented By WILLARD FRANCIS PETRY Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS February 1980 Political Science THE AESTHETIC COMMUNITY: THE SOCIAL AND POLITICAL THOUGHT OF PAUL GOODMAN A Thesis Presented By WILLARD FRANCIS PETRY Approved as to style and content by: Dean Albertson, Member Glen Gordon, Department Head Political Science n Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2016 https://archive.Org/details/ag:ptheticcommuni00petr . The repressed unused natures then tend to return as Images of the Golden Age, or Paradise, or as theories of the Happy Primitive. We can see how great poets, like Homer and Shakespeare, devoted themselves to glorifying the virtues of the previous era, as if it were their chief function to keep people from forgetting what it used to be to be a man. -

Jewish Dimensions in Modern Visual Culture: Antisemitism, Assimilation, Affirmation

Fairfield University DigitalCommons@Fairfield History Faculty Book Gallery History Department 2009 Jewish Dimensions in Modern Visual Culture: Antisemitism, Assimilation, Affirmation Rose-Carol Washton Long Matthew Baigell Milly Heyd Gavriel D. Rosenfeld Fairfield University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fairfield.edu/history-books Copyright 2009 Brandeis University Press Content archived her with permission from the copyright holder. Recommended Citation Washton Long, Rose-Carol; Baigell, Matthew; Heyd, Milly; and Rosenfeld, Gavriel D., "Jewish Dimensions in Modern Visual Culture: Antisemitism, Assimilation, Affirmation" (2009). History Faculty Book Gallery. 14. https://digitalcommons.fairfield.edu/history-books/14 This item has been accepted for inclusion in DigitalCommons@Fairfield by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Fairfield. It is brought to you by DigitalCommons@Fairfield with permission from the rights- holder(s) and is protected by copyright and/or related rights. You are free to use this item in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses, you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 12 Gavriel D. Rosenfeld Postwar Jewish Architecture and the Memory of the Holocaust When Daniel Libeskind was named in early 2003 as the mas- ter planner in charge of redeveloping the former World Trade Center site in lower Manhattan, most observers saw it as a personal triumph that tes- tifi ed to his newfound status as one of the world’s most respected architects. -

AMERICAN MEMORIAL to SIX MILLION JEWS of EUROPE,Me

AMERICAN MEMORIAL TO SIX MILLION JEWS OF EUROPEme, . 165 WEST 46th STREET Suite 814 NEW YORK 19, N. Y. - Tel. PLaza 7-8430 Circle 6-2880 HONORARY SPONSORS COMMITTEE: BOARD OF DIRECTORS ADVISORY DESIGN COMMITTEE: Honorary Chairman Honorary Chairman CHARLES NAGEL, JR. HON. WILLIAM O'DWYER HON. HUGO E. ROGERS Director, Brooklyn Museum of Art and Sciences Mayor, The City of New York President, Borough of Manhattan Chairman GEOFFREY PARSONS HON. ROBERT MOSES, Member ex-officio I. ROGOSIN Editor, New York Herald Tribune Committee and Board Members: Secretary REV. DR. D. de SOLA POOL Rev. Carlyle Adams PROF. JAMES H. SHELDON FRANCIS HENRY TAYLOR Rabbi Isaac Alcalay Director, Metropolitan Museum of Art Congressman Walter G. Andrews Administrative Chairman Murray Antkies A. R. LERNER Joseph R. Apfel Hon. Thurman Arnold Sholem Asch Rev. Henry A. Atkinson Hon. Joseph C. Baldwin Prof. Salo W. Baron Hon. John J. Bennett B. Bialostotsky February 2, 1950 Justice Hugo L. Black Joseph G. Blum Gay H. Brown Hon. James A. Burke Congressman William T. Byrne Rudolph Callman The Rev. Dr. D. de Sola i^ool Eddie Cantor Hon. John Cashmore 99 Central Park West Congressman Emanuel Celler Prof. Emanuel Chapman New York 23, N. Harry Woodburn Chase Alexander P. Chopin Stuart Constable Hon. Edward Corsi My dear Dr. de Sola Pool: Myer Dorfman Justice William O. Douglas Congressman Edward J. Elsaesser Mrs. Moses P. Epstein In reply to your letter of January 31st, I wi3h Rev. Frederick L. Fagley Hon. James A. Farley to inform you that Mr. Joseph Ho veil was never asked to Abraham Feinberg Rabbi Abraham J. -

Banning Cars from Manhattan

Paul and Percival Goodman Banning Cars from Manhattan 1961 The Anarchist Library Contents Peripheral Parking.......................... 4 Roads.................................. 4 Means, etc................................ 6 Conclusion............................... 6 2 We propose banning private cars from Manhattan Island. Permitted mo- tor vehicles would be buses, small taxis, vehicles for essential services (doctor, police, sanitation, vans, etc.), and the trucking used in light industry. Present congestion and parking are unworkable, and other proposed solu- tions are uneconomic, disruptive, unhealthy, nonurban, or impractical. It is hardly necessary to prove that the actual situation is intolerable. “Motor trucks average less than six miles per hour in traffic, as against eleven miles per hour for horse drawn vehicles in 1911.” “During the ban on nonessential vehicles during the heavy snowstorm of February 1961, air pollution dropped 66 per cent.” (New York Times, March 13, 1961.) The street widths of Manhattan were designed, in 1811, for buildings of one to four stories. By banning private cars and reducing traffic, we can, in most areas, close off nearly nine out of ten cross-town streets and every second north-south avenue. These closed roads plus the space now used for off-street parking will give us a handsome fund of land for neighborhood relocation. At present over 35 percent of the area of Manhattan is occupied by roads. Instead of the present grid, we can aim at various kinds of enclosed neighborhoods, in approximately 1200-foot to 1600-foot superblocks. It would be convenient, however, to leave the existing street pattern in the main midtown shopping and business areas, in the financial district, and wherever the access for trucks and service cars is imperative. -

PAUL GOODMAN (1911-1972) Edgar Z

The following text was originally published in Prospects : the quarterly review of comparative education (Paris, UNESCO : International Bureau of Education), vol . XXIII, no . 3/4, June 1994, p. 575-95. ©UNESCO: International Bureau of Education, 1999 This document may be reproduced free of charge as long as acknowledgement is made of the source. PAUL GOODMAN (1911-1972) Edgar Z. Friedenberg1 Paul Goodman died of a heart attack on 2 August 1972, a month short of his 61st birthday. This was not wholly unwise. He would have loathed what his country made of the 1970s and 1980s, even more than he would have enjoyed denouncing its crassness and hypocrisy. The attrition of his influence and reputation during the ensuing years would have been difficult for a figure who had longed for the recognition that had eluded him for many years, despite an extensive and varied list of publications, until Growing up absurd was published in 1960, which finally yielded him a decade of deserved renown. It is unlikely that anything he might have published during the Reagan-Bush era could have saved him from obscurity, and from the distressing conviction that this obscurity would be permanent. Those years would not have been kind to Goodman, although he was not too kind himself. He might have been and often was forgiven for this; as well as for arrogance, rudeness and a persistent, assertive homosexuality—a matter which he discusses with some pride in his 1966 memoir, Five years, which occasionally got him fired from teaching jobs. However, there was one aspect of his writing that the past two decades could not have tolerated. -

“For a World Without Oppressors:” U.S. Anarchism from the Palmer

“For a World Without Oppressors:” U.S. Anarchism from the Palmer Raids to the Sixties by Andrew Cornell A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Social and Cultural Analysis Program in American Studies New York University January, 2011 _______________________ Andrew Ross © Andrew Cornell All Rights Reserved, 2011 “I am undertaking something which may turn out to be a resume of the English speaking anarchist movement in America and I am appalled at the little I know about it after my twenty years of association with anarchists both here and abroad.” -W.S. Van Valkenburgh, Letter to Agnes Inglis, 1932 “The difficulty in finding perspective is related to the general American lack of a historical consciousness…Many young white activists still act as though they have nothing to learn from their sisters and brothers who struggled before them.” -George Lakey, Strategy for a Living Revolution, 1971 “From the start, anarchism was an open political philosophy, always transforming itself in theory and practice…Yet when people are introduced to anarchism today, that openness, combined with a cultural propensity to forget the past, can make it seem a recent invention—without an elastic tradition, filled with debates, lessons, and experiments to build on.” -Cindy Milstein, Anarchism and Its Aspirations, 2010 “Librarians have an ‘academic’ sense, and can’t bare to throw anything away! Even things they don’t approve of. They acquire a historic sense. At the time a hand-bill may be very ‘bad’! But the following day it becomes ‘historic.’” -Agnes Inglis, Letter to Highlander Folk School, 1944 “To keep on repeating the same attempts without an intelligent appraisal of all the numerous failures in the past is not to uphold the right to experiment, but to insist upon one’s right to escape the hard facts of social struggle into the world of wishful belief. -

Paul Goodman and the Biography of Sexual Modernity David S

Document generated on 10/02/2021 9:40 p.m. Journal of the Canadian Historical Association Revue de la Société historique du Canada Paul Goodman and the Biography of Sexual Modernity David S. Churchill The Biographical (Re)Turn Article abstract Volume 21, Number 2, 2010 This article is a preliminary exploration of the relationship between the auto-biographical writings of radical US intellectual Paul Goodman and his URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1003087ar theorizing of sexuality’s links to the project of political liberation. Goodman’s DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1003087ar life writing was integrated into his social and political critique of mid-twentieth century society, as well as his more scholarly pursuits of See table of contents psychology and sociology. In this way, Goodman’s work needs to be seen as generative of the dialectic of sexually modernity, which integrated intimate queer sexual experiences with conceptual, intellectual, and elite discourses on sexuality. Publisher(s) The Canadian Historical Association / La Société historique du Canada ISSN 0847-4478 (print) 1712-6274 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Churchill, D. S. (2010). Paul Goodman and the Biography of Sexual Modernity. Journal of the Canadian Historical Association / Revue de la Société historique du Canada, 21(2), 47–60. https://doi.org/10.7202/1003087ar All Rights Reserved © The Canadian Historical Association / La Société This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit historique du Canada, 2010 (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. -

VOID and MEDIUM in POSTWAR US CULTURE by Matthew Allen

THE PROJECTOR RESTS ON A PILE OF BOOKS: VOID AND MEDIUM IN POSTWAR U.S. CULTURE By Matthew Allen Tierney A.B., Cornell University, 2000 M.A., University of California—Santa Cruz, 2006 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Modern Culture and Media at Brown University. Providence, Rhode Island 2012 © Copyright 2012 by Matthew Allen Tierney ii This dissertation by Matthew Allen Tierney is accepted in its present form by the Department of Modern Culture and Media as satisfying the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Date Ellen Rooney, Advisor Recommended to the Graduate Council Date Rey Chow, Reader Date Daniel Kim, Reader Date Michael Silverman, Reader Approved by the Graduate Council Date Peter M. Weber, Dean of the Graduate School iii MATTHEW ALLEN TIERNEY EDUCATION Ph.D., Modern Culture & Media, Brown University (Providence, RI)—2012 M.A., Literature, University of California (Santa Cruz, CA)—2006 A.B. Cum Laude, American Studies, Cornell University (Ithaca, NY)—1999 PUBLICATIONS “Oh no, not again!: Representability and a Repetitive Remark.” Image & Narrative 11:2 (2010) Review of Jonathan Auerbach, Dark Borders: Film Noir & American Citizenship. Film Criticism 36:2 (2012) SELECTED PRESENTATIONS: “A Breath of Dissent: Novel Histories and Political Denarration” Society for Novel Studies, 2012 “Breathing, Talking Politics: Disastrous Liberalism and the Prose of Mere Dissent” American Comparative Literature Association,