The Persian Gulf in Modern Times, Edited by Lawrence G

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Economic Gateway for the Nation

Adani Ports and Special Economic Zone Limited An Economic Gateway for the Nation Thinking big Doing better Everyone has a philosophy or a set of rules they work by. Ours is Thinking big, Doing better. Over the course of 25 years, we discovered that starting a large scale business has served not only us, but also the nation. This in turn has affected millions of lives, making them simpler and better. This is why we think big, so we can do better. Each action we take ripples throughout the society and benefits people in ways we never even dreamt of. Adani Ports and Special Economic Zone Limited is an undisputed leader in the Indian port sector. 1 Adani Ports and Special Economic Zone APSEZ provides seamlessly integrated Exceptional features of APSEZ services across three verticals, i.e. Ports Ports, Logistics and SEZ • Deep water, all-weather, direct berthing • One stop solution for business facilities • Pan-India presence • Large scale mechanisation • Largest integrated infrastructure company • Connectivity to national highway and • Dedicated, committed and passionate rail networks team to provide superior services • Scope for major expansion at our ports • Technology driven system and processes • Operational benchmarks comparable to the best in the world 2 3 Strategic Advantages at Adani Kila - Raipur Patli Kishangarh Mundra Tuna Dahej Dhamra Hazira Vizag Ports Mormugao Terminals ICDs Kattupalli Ennore Vizhinjam Adani Ports: Pioneer on multiple fronts • Single window interface system for • Specialised infrastructure evolved customers that -

Ft1 . 17Og5z5aor C-Rs @

18. Copy of colour coded all bathymetry sheet/survey done for M/s AKBTPL in last three years for pocket berths, turning circle, approach channel, disposal ground etc. 1.9. Facilities/machinery/equipment available with M/s AKBTPL, Adani Group for existing and proposed dredging. 20. At a rate of proposed capital and maintenance dredging volume after expansion, disposal ground will fill after how many years? 21. Who is Port Authority and what is the role will be of Port Authority as per Table - 6 - 2. 22. List of technical staff of Port Authority in field of environment with details of educational qualification to look after the assigned role as per Table - 6 - 2. 23. Map showing mangroves cover around the 10 Km radius of M/s AKBTPL. 24. Please refer page 05 of 10 of Annexure-01. Copy of bifurcation made by GCMA regarding Active or Inactive mudflat. If not done, who will be the authority to ascertain the same and signification thereof in classification/preparation of CRZ Map. 25. Copy of Ietter forwarded to GCMA to ascertain Mudflat (active or inactive) by CRZ mapping a u t h o rity/P roject Proponent. 26. Copy of report prepared by M/s Central Water and Power Research Station, Pune for the studies related to dredging. 21. Copy of action plan to comply with lacuna mentioned in summery note (lmplementation status of conditions) by Dr. H. V. C. Chary Guntupalli of RO, MoEF, Bhopal attached as An nexu re-04. 28. Details of presence of flora and fauna having conservation status of as per IUCN Red data. -

Adani Kandla Bulk Terminal Pvt. Ltd

15 mm 2 mm 25 mm 18 mm FUGRO GEOTECH PVT. LTD. ADANI KANDLA BULK TERMINAL PVT. LTD. SUB-SOIL INVESTIGATION FOR JETTY & APPROACH TRESTLE FOR DRY BULK TERMINAL AT TUNA, KANDLA INDIA FINAL REPORT REPORT NO: FGTL/AKBTPL/ED/452/12/REV-4 FEBRUARY 06, 2013 FUGRO GEOTECH PVT. LTD. ADANI KANDLA BULK TERMINAL PVT. LTD. SUB-SOIL INVESTIGATION FOR JETTY & APPROACH TRESTLE FOR DRY BULK TERMINAL AT TUNA, KANDLA FINAL REPORT Report No. : FGTL/AKBTPL/ED/452/12/Rev-4 December 2012 REPORT ISSUE STATUS Report Date Report Status Checked Approved Issue No. <00> December 12, 2012 Report ISH ISH / SJ <01> December 19, 2012 Report ISH ISH / SJ <02> January 11, 2013 Report ISH ISH / SJ <03> February 02, 2013 Draft Final Report ISH ISH / SJ <04> February 06, 2013 Final Report ISH ISH / SJ Client: Geotechnical Contractor: ADANI KANDLA BULK TERMINAL PVT. LTD. FUGRO GEOTECH PVT. LTD. PMC House, Fugro Onshore Geotechnics Nr Mithakhali Circle, Plot No.51, Navrangpura, Sector-6, Sanpada, Ahmedabad 380 009 Navi Mumbai – 400 705 Gujarat (India) Maharashtra (India) FUGRO GEOTECH PVT. LTD. TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ....................................................................................................................... 4 LIST OF TABLES ................................................................................................................................. 5 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS ................................................................................................................... 6 APPENDICES ..................................................................................................................................... -

Economic Development (2-Downloads)

The Developed and Developing World Income GNI per capita, World Bank Atlas method, 2007 Greenland (Den) Low-income countries ($935 or less) Faeroe Lower-middle-income countries ($936–$3,705) Islands Iceland (Den) Upper-middle-income countries ($3,706–$11,455) Norw High-income countries ($11,456 or more) The Netherlands Canada United Kingdom no data Isle of Man (UK) Denm Ireland Ge Channel Islands (UK) Belgium Luxembourg France Switzerl I Liechtenstein Andorra Spain United States Monaco Portugal Bermuda Gibraltar (UK) (UK) Tu British Virgin Islands (UK) Middle East & North Africa Morocco The Bahamas Algeria Mexico Dominican $2,794 Former Republic Spanish Cayman Islands (UK) Puerto Sahara Cuba Rico (US) US Virgin St. Kitts and Nevis Islands (US) Antigua and Barbuda Mauritania Belize Jamaica Haiti Cape Verde Guadeloupe (Fr) Mali N Guatemala Honduras Aruba Dominica Senegal Martinique (Fr) El Salvador (Neth) St. Lucia The Gambia Nicaragua Barbados Guinea-Bissau Burkina Faso Guinea Panama Benin Costa Rica Trinidad St. Vincent and the Grenadines Niger and Tobago Grenada Sierra Leone Côte Ghana d'Ivoire Netherlands R.B. de French Guiana Liberia Ca Antilles (Neth) Venezuela Guyana (Fr) Togo Colombia Equato Kiribati Latin America & Caribbean Suriname São Tomé and Príncipe Ecuador $5,540 Peru Brazil French Polynesia (Fr) Bolivia Brazil Paraguay $5,910 Uruguay Chile Argentina Source: Data from Atlas of Global Development, 2nd ed., pp. 10–11. © Collins Bartholomew Ltd., 2010. Russian Federation Europe & Central Asia $7,560 $6,051 Sweden way Finland Russian Federation Estonia Latvia nmark Lithuania Czech Republic Belarus Slovak Republic Poland ermany Slovenia m Croatia Ukraine Kazakhstan Austria Hungary Moldova Serbia rland Romania Bosnia and Herzegovina Mongolia Italy FYR Macedonia Montenegro Bulgaria Uzbekistan Georgia Kyrgyz Republic Albania Azerbaijan Dem. -

Fertilizer Logistics Port Handling Operations and Coastal Shipping

FAI Programme on Fertilizer Logistics Port Handling Operations and Coastal Shipping 6-9 March, 2019 Quality Inn Palms, Gandhidham, Near Deendayal Port Trust, Kandla, Gujarat THE FERTILIZER ASSOCIATION OF INDIA ‘FAI House’, 10, Shaheed Jit Singh Marg, New Delhi Dear Friends, FAI has conducted fifteen programmes on Import, Shipping and Port Handling Operations in India and Abroad. In addition to organization of thirteen programmes at different port locations in India, two programmes were also conducted in Muscat (Sultanate of Oman) and Dubai. The next programme is scheduled at Gandhidham, Gujarat. The programme is designed to give exposure to practical as well as theoretical aspects of port handling operations of fertilizers/raw materials/intermediates, etc. Participants will be taken to the Deendayal Port, Kandla; Adani Port, Mundra and Tuna Port, Tuna to show them the activities being undertaken for handling of imported fertilizers/raw materials and further logistics operations at these ports. The programme is scheduled for four days during 6-9 March, 2019 at Quality Inn Palms, Gandhidham, Near Deendayal Port, Kandla, Gujarat. We are making our best efforts to bring the senior officials from the Department of Fertilizers, Ministry of Shipping, officials of the Deendayal Port Trust, Kandla; Adani Port, Mundra and Tuna Port, Tuna, General Insurance Company, Stevedoring and Handling Agencies and the Consultants to participate in the programme. The deliberations will be more interesting and meaningful with the participation of senior officials. The programme topics, registration form and other details are given in this brochure. We request you to send the nominations from your organization for this event. -

P1-13 Layout 1

SUBSCRIPTION THURSDAY, DECEMBER 11, 2014 SAFAR 19, 1436 AH www.kuwaittimes.net Girls sued Unwelcome The Real Fouz: Prosecutors will for ‘offensive’ dogs find Dos and seek murder social media care at rare don’ts for conviction video, images3 Iran13 shelter healthy37 nails against15 Pistorius Ban on Indian workers Min 09º Max 26º looms as spat escalates High Tide 01:27 & 15.52 Low Tide Meeting to resolve maid guarantee dispute fails 09:08 & 21:03 40 PAGES NO: 16369 150 FILS By Staff Reporter Kuwait Sunil Jain and officials from the for- Delhi in protest against the decision. Filipinos 185,000 and Bangladeshis at eign and interior ministries, during which According to the sources, immigration 180,000. ‘Bomb’ found KUWAIT: A threat to ban the recruitment the issue was discussed at length. departments could start the ban on Indians The Indian embassy has repeatedly of Indian laborers into Kuwait may be Assistant undersecretary for passports from today or from next week unless a com- explained that the bank guarantee is a near ministry implemented as soon as today after a high- and residency Maj Gen Mazen Al-Jarrah promise is reached. Based on the latest offi- decision taken by the Indian government level diplomatic meeting failed to resolve was present at the meeting. Jarrah has cial figures, the number of Indians in Kuwait in 2007 and has been applied in several the dispute over an Indian decision to repeatedly blasted the decision and threat- has rapidly swelled to close to 800,000, countries including all other Gulf states. KUWAIT: A suspected bomb was found near the impose a $2,500 (KD730) bank guarantee ened to impose a ban on Indians. -

Save the Coast, Save the Fishers

Save the Coast, Save the Fishers Report of “Machhimar Adhikar Rashtriya Abhiyan” May - November 2008 National Fishworkers’ Forum 20/4 Sil Lane, Kolkata, West Bengal, India Email: [email protected], [email protected] www.coastalcampaign.page.tl Save the Coast, Save the Fishers Report of “Machhimar Adhikar Rashtriya Abhiyan”, May - November 2008 Photographs Front cover: Debasis Shayamal (NFF) Back cover: Prem Piram (Jagar and Delhi Solidarity Group) Support: DISHA Printed at V & M PRINTS P LTD, No: 111, Kundrathur Road, “Porur Tower” Porur, Chennai - 600 116 Email: [email protected] Telephone No: 044 - 64582790 / 91 / 92 Fax No: 044 - 24828781 Published by National Fishworkers’ Forum 20/4 Sil Lane Kolkata – 700015 West Bengal Telefax: 033-23283989 Email: [email protected], [email protected] www.coastalcampaign.page.tl © NFF 2008 Save the Coast, Save the Fishers Report of “Machhimar Adhikar Rashtriya Abhiyan” May - November 2008 National Fishworkers’ Forum 20/4 Sil Lane, Kolkata, West Bengal, India Email: [email protected], [email protected] www.coastalcampaign.page.tl Contents Foreword ........................................................................................... iii Acknowledgements ........................................................................................... v Introduction ........................................................................................... vii Hotspots: Map of India ......................................................................................... viii NFF Dharna: New Delhi -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses British political relation with Kuwait 1890-1921 Al-Khatrash, F. A. How to cite: Al-Khatrash, F. A. (1970) British political relation with Kuwait 1890-1921, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/9812/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. BRITISH POLITICAL RELATIONS WITH KUWAIT 1890-1921 . by F.A. AL-KHATRASH B.A. 'Ain Shams "Cairo" A thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Arts in the University of Durham October 1970 CONTENTS Page Preface i - iii / Chapter One General History of Kuwait from 1890-1899 1 References 32 Chapter Two International Interests in Kuwait 37 References 54 Chapter Three Turkish Relations with Kuwait 1900-1906 57 References 84 J Chapter Four British Political Relations with Kuwait 1904-1921 88 References 131 Conclusion 135 Appendix One Exclusive Agreement: The Kuwaiti sheikh and Britain 23 January 1899 139 Appendix Two British Political Representation in the Persian Gulf 1890-1921 141 Appendix Three United Kingdom*s recognition of Kuwait as an Independent State under British Protection. -

Table of Contents

Table of Contents Beacon Conference Description and Steering Committee Members………………………………………….3 Community College Sponsors, Other Sponsors…………………………………………………………………………..4 Outstanding Papers Jon Carlson The Balance of Nature and the Hunger of Children: An Ethical Exploration of Genetically Modified Organisms………………………….…….…………………5 Sarah Chan Redefining Beauty Standards: The Negative Influence of the Western Aesthetic of Thinness……………………………………………………….…………..15 Rakesh Chopde ‘Caste-ing’ Call for the Social Network: Leveling the Playing Field in India…………35 Antonio Concolino So What’s the Deal with the Value of the Renminbi Anyway?..............................53 Laura Duran Shakespeare’s Ariel and Caliban: The Others…………………………………………………….63 Erica Espinosa The Good, the Bad, and the Hope: Remittances & Globalization……………….………73 Samuel Han The End of Religion: An Epistemo-personal Exploration……………….……………………90 Adrianne Kirk Medical Miracles: The Price of Creativity? Posthumous Diagnoses of Three Great Artists…………………………………………………………………………………….104 Hannah Knowlton The Irish Potato Famine: Act of Genocide………………………………………………………..122 Diane Lameira Creating the Terrorist: The Psychology of Group Dynamics……………………………..133 1 Ryan McGrail The DeLacey Family; the True Creators of Frankenstein’s Creature………………….149 Joselida Mercado Sowing Wild Oates: Sex, Fairy Tales and Rock and Roll……………………………………157 Siomara Parada Containing the Scourge of AIDS: A Case Study on Brazil…………………………………..164 Theresa Price Kidneys Anyone?.................................................................................................182 -

Adani Port Brochure 8Th July

Adani Ports and Special Economic Zone Limited An economic gateway for the nation Ports and Logistics Growth, the way it is meant to be. Growth, to us, isn't about the businesses we're involved in. Growth is about the real impact we can create. It's about the lives we can touch, the communities we can nourish, the future we can inspire. Vision With our sheer size of operations, we have been able to reach out to the remotest of geographies To be a world class leader in businesses that with ease. Be it power transmission or solar energy generation or agri logistics, we go for large scale enrich lives and contribute to nations in execution that benefits millions of Indians. building infrastructure through sustainable We are proud of this quality of our operations, which we have consciously extended beyond our value creation. businesses, to impact healthcare, education, employment generation and creation of sustainable livelihoods for the communities that deserve them. It is the belief that growth can lead to goodness, which inspires us and drives us. Adani Ports and Special Economic Zone The undisputed leader in Indian ports sector APSEZ provides seamlessly integrated Exceptional features of APSEZ Ports services across four verticals, i.e. Ports, Logistics, SEZ and Dredging. • Deep-water, all-weather, direct berthing facilities • One-stop solution for business • Large-scale mechanization • Pan-India presence • Connectivity to national highways and • Largest commercial port operator and rail networks integrated logistics player • Scope for major -

S.No. State Zone Type of Customs Stations(Port,ACC,ICD,C FS

Whether Type of Customs connecte Functioning Port S.No. State Zone Stations(Port,ACC,ICD,C Name of Station d / Non code FS and LCS) through functioning EDI Andaman and 1 Kolkata Port Port Blair INIXZ1 YES EDI enabled Nicobar Islands Andhra 2 Vishakahpatnam Port Gangavaram Port, Andhra Pradesh INGGV1 YES EDI enabled Pradesh Andhra 3 Vishakahpatnam ICD Icd Marripalam, District - Guntur, A.P. INGNR6 YES EDI enabled Pradesh Andhra 4 Vishakahpatnam Port Custom House Port Area Kakinada 533007 INKAK1 YES EDI enabled Pradesh Andhra 5 Vishakahpatnam Port Ices Krishnapatnam Port, Nellore-524003 INKRI1 YES EDI enabled Pradesh Andhra Icd Thimmapur, 11-60/5-7 Thimmapur 6 Hyderabad ICD INTMX6 YES EDI enabled Pradesh 509325 Ap Andhra Custom House Port Area Viskhapatnam 7 Vishakahpatnam Port INVTZ1 YES EDI enabled Pradesh 530035 Andhra 8 Vishakahpatnam ACC Air Cargo Complex Visakhapatnam INVTZ4 YES EDI enabled Pradesh 9 Assam GUWAHATI ICD Concor, Icd Amingaon, Guwahati- 781031 INAMG6 YES EDI enabled 10 Assam GUWAHATI ACC Guwahati Air Cargo INGAU4 YES EDI enabled Leveraging Technology For Serving Taxpayers Whether Type of Customs connecte Functioning Port S.No. State Zone Stations(Port,ACC,ICD,C Name of Station d / Non code FS and LCS) through functioning EDI 11 Bihar Patna LCS Bairgania INBGUB YES EDI enabled 12 Bihar Patna LCS Bhimnagar INBNRB YES EDI enabled 13 Bihar Patna LCS Bhitamore INBTMB YES EDI enabled 14 Bihar Patna LCS Galgalia INGALB YES EDI enabled 15 Bihar Patna LCS Jayanagar INJAYB YES EDI enabled 16 Bihar Patna LCS Lcs Jogbani, Dist:Araria, -

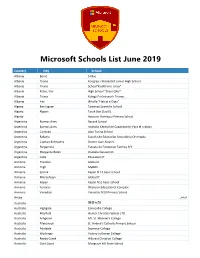

Microsoft Schools List June 2019

Microsoft Schools List June 2019 Country City School Albania Berat 5 Maj Albania Tirane Kongresi i Manastirit Junior High School Albania Tirane School"Kushtrimi i Lirise" Albania Patos, Fier High School "Zhani Ciko" Albania Tirana Kolegji Profesional i Tiranës Albania Fier Shkolla "Flatrat e Dijes" Algeria Ben Isguen Tawenza Scientific School Algeria Algiers Tarek Ben Ziad 01 Algeria Azzoune Hamlaoui Primary School Argentina Buenos Aires Bayard School Argentina Buenos Aires Instituto Central de Capacitación Para el Trabajo Argentina Cordoba Alan Turing School Argentina Rafaela Escuela de Educación Secundaria Orientada Argentina Capitan Bermudez Doctor Juan Alvarez Argentina Pergamino Escuela de Educacion Tecnica N°1 Argentina Margarita Belen Graciela Garavento Argentina Caba Educacion IT Armenia Hrazdan Global It Armenia Tegh MyBOX Armenia Syunik Kapan N 13 basic school Armenia Mikroshrjan Global IT Armenia Kapan Kapan N13 basic school Armenia Yerevan Ohanyan Educational Complex Armenia Vanadzor Vanadzor N19 Primary School الرياض Aruba Australia 坦夻易锡 Australia Highgate Concordia College Australia Mayfield Hunter Christian School LTD Australia Ashgrove Mt. St. Michael’s College Australia Ellenbrook St. Helena's Catholic Primary School Australia Adelaide Seymour College Australia Wodonga Victory Lutheran College Australia Reedy Creek Hillcrest Christian College Australia Gold Coast Musgrave Hill State School Microsoft Schools List June 2019 Country City School Australia Plainland Faith Lutheran College Australia Beaumaris Beaumaris North Primary School Australia Roxburgh Park Roxburgh Park Primary School Australia Mooloolaba Mountain Creek State High School Australia Kalamunda Kalamunda Senior High School Australia Tuggerah St. Peter's Catholic College, Tuggerah Lakes Australia Berwick Nossal High School Australia Noarlunga Downs Cardijn College Australia Ocean Grove Bellarine Secondary College Australia Carlingford Cumberland High School Australia Thornlie Thornlie Senior High School Australia Maryborough St.