Economic Development (2-Downloads)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Contemporary Theories of Economic Development

Development Economics 355 Lecture Notes 3-1 Week 3-4 notes (TS ch. 4, E. ch. 8) Contemporary Theories of Economic Development • These notes cover some more recent theories of economic growth and development. • We look at departures from the neoclassical framework of unique equilibrium and perfectly functioning markets. I. Underdevelopment as coordination failure • Emphasis on complementarities between various conditions necessary for successful development • Complementarity: when an action taken by one firm or individual increases the incentives of (makes it more profitable or less costly for) other economic agents to take similar actions (this action does not have to be a good thing!) • Examples: corruption, not throwing garbage on the street; using Windows, QWERTY, etc. Ask students for more examples! * complementarities involve positive externalities across agents (the more I do something, the cheaper for you is to do the same; the more people do something, the cheaper/better for others to do the same). * can create status quo bias – being stuck in a possibly bad situation (e.g. most people using Windows today because DOS was very successful early on). Very hard to make people switch. * In contrast, when we have negative externalities (e.g. congestion), doing more of something makes it harder/more expensive to do the same (e.g. traffic on two bridges) – everyone wants to do the opposite (not the same) action (e.g. take the other bridge). 2. Coordination failure : a state of affairs in which agents’ inability to coordinate their behavior (choices) leads to a stable outcome (equilibrium) in which they are all worse off than in an alternative situation (also equilibrium). -

An Application of a Big Push Model to Nigerian Economy

International Journal of Economics, Commerce and Management United Kingdom Vol. III, Issue 4, April 2015 http://ijecm.co.uk/ ISSN 2348 0386 ENTREPRENEURIAL INNOVATION AND CO-ORDINATION FAILURE: AN APPLICATION OF A BIG PUSH MODEL TO NIGERIAN ECONOMY Kadiri Kayode School of Management Science National, Open University Of Nigerian, Nigeria [email protected] Genevieve Kelikume Center For Lifelong Learning National, Open University Of Nigeria, Nigeria [email protected] Atoyebi Kehinde Olusegun Lagos State University, Department Of Economics, Faculty of Social Sciences, Nigeria [email protected] Abstract This study critically examines the interconnectivity between entrepreneur innovation and co- ordination failure in Nigeria. This study follows the standard assumption of the big-push model by developing a model that analyses the causes of co-ordination failure as well as the government failure. This study observes that as a result of the structure of Nigeria economy presently, state intervention in the establishment of state owned enterprises should be reduced to enhance entrepreneur participation in employment generation and productivity improvement because of the rent seeking behaviour by a particular interest group who may disallowing successfulness of government policy. Though, the big-push policy is needed to pave way for industrialization. Keywords: Entrepreneurs innovation, co-ordination failure, big push, state owned enterprises. Licensed under Creative Common Page 1 © Kadiri, Genevieve & Atoyebi INTRODUCTION Entrepreneur’s innovation according to Schumpeter (1928,1939) is a perpetual gales of creative destruction which serves as the driving forces of growth rates in a capitalist system. Schumpeter is was not a technological determinist but recognized the social and organization forces that played the key role in his cyclical process of industrial change. -

DEVELOPMENT THEORY and the ECONOMICS of GROWTH Jaime

1 DEVELOPMENT THEORY AND THE ECONOMICS OF GROWTH Jaime Ros University of Notre Dame June 1999 DRAFT 2 Contents Introduction 1. The book’s aim and scope 2. Overview of the book 1. Some stylized facts 1. Incomes per capita across the world 2. Growth rates since 1965 Appendix 2. A mature economy: growth and factor accumulation 1. The Solow model 2. Empirical shortcomings 3. Extensions: technology and human capital 4. Endogenous investment rates Appendix 3. Labor surplus economies 1. The Lewis model 2. Are savings rates correlated with profit shares? 3. Surplus labor and the elasticity of labor supply 4. Efficiency wages and underemployment Appendix 4. Increasing returns, external economies, and multiple equilibria 3 1. Increasing returns to scale and efficiency wages 2. Properties and extensions 3. Empirical evidence Appendix 5. Internal economies, imperfect competition and pecuniary externalities 1. The big push in a multisectoral economy 2. Economies of specialization and a Nurksian trap 3. Vertical externalities: A Rodan-Hirschman model 6. Endogenous growth and early development theory 1. Models of endogenous growth 2. Empirical assessment 3. A development model with increasing returns and skill acquisition 7. Trade, industrialization, and uneven development 1. Openness and growth in the neoclassical framework 2. The infant industry argument as a case of multiple equilibria 3. Different rates of technical progress 4. Terms of trade and uneven development Appendix 8. Natural resources, the Dutch disease, and the staples thesis 1. On Graham's paradox 2. The Dutch disease under increasing returns 3. Factor mobility, linkages, and the staple thesis 4. An attempt at reconciliation: Two hybrid models Appendix 9. -

P1-13 Layout 1

SUBSCRIPTION THURSDAY, DECEMBER 11, 2014 SAFAR 19, 1436 AH www.kuwaittimes.net Girls sued Unwelcome The Real Fouz: Prosecutors will for ‘offensive’ dogs find Dos and seek murder social media care at rare don’ts for conviction video, images3 Iran13 shelter healthy37 nails against15 Pistorius Ban on Indian workers Min 09º Max 26º looms as spat escalates High Tide 01:27 & 15.52 Low Tide Meeting to resolve maid guarantee dispute fails 09:08 & 21:03 40 PAGES NO: 16369 150 FILS By Staff Reporter Kuwait Sunil Jain and officials from the for- Delhi in protest against the decision. Filipinos 185,000 and Bangladeshis at eign and interior ministries, during which According to the sources, immigration 180,000. ‘Bomb’ found KUWAIT: A threat to ban the recruitment the issue was discussed at length. departments could start the ban on Indians The Indian embassy has repeatedly of Indian laborers into Kuwait may be Assistant undersecretary for passports from today or from next week unless a com- explained that the bank guarantee is a near ministry implemented as soon as today after a high- and residency Maj Gen Mazen Al-Jarrah promise is reached. Based on the latest offi- decision taken by the Indian government level diplomatic meeting failed to resolve was present at the meeting. Jarrah has cial figures, the number of Indians in Kuwait in 2007 and has been applied in several the dispute over an Indian decision to repeatedly blasted the decision and threat- has rapidly swelled to close to 800,000, countries including all other Gulf states. KUWAIT: A suspected bomb was found near the impose a $2,500 (KD730) bank guarantee ened to impose a ban on Indians. -

Development Economics

Development Economics Alessandra Pelloni Lectures II April 2018 Alessandra Pelloni (Lectures II) Development April2018 1/38 We will introduce some key ideas that can explain persistent underdevelopment Complementarities and coordination failures Big push Capital Market Imperfections and Inequality O’ring Growth diagnostics But before that: Early Theories of Economic Growth and Development Alessandra Pelloni (Lectures II) Development April2018 2/38 1950s and 1960s Theories of Economic Growth and Development Scientific interest in development began following World War II. Economist had as a guide the experience of the Marshall Plan, under which massive amounts of U.S. financial and technical assistance enabled the war-torn countries of Europe to rebuild and modernize their economies in a matter of years as well as the lessons of economic history: after all modern industrial nations were once undeveloped agrarian societies. Theorists of the 1950s and 1960s viewed the process of development as a series of successive stages of economic growth through which all countries must pass. Alessandra Pelloni (Lectures II) Development April2018 3/38 Rostow’sStages of Economic Growth model (1960) According to the american economic historian the five basic stages in which all countries can be classified are: Traditional society (subsistence agriculture or hunting and gathering);Transitional society(more productive, commercial agriculture, urbanization, formation of national identities); Take-off( industrialization, technological breakthroughs).Mature stage (Diversification of the industrial base, Transport infrastructure); and society of mass consumption. Alessandra Pelloni (Lectures II) Development April2018 4/38 The Harrod Domar model The right mixture of saving, investment, and foreign aid were then all that was necessary to enable developing nations to proceed along an economic growth path that had historically been followed by the more developed countries. -

FOR GROWTH and SUSTAINABILITY in AFRICA - EVIDENCE from GHANA 1 1 1 Kwamina E

“THE GREATER PUSH” FOR GROWTH AND SUSTAINABILITY IN AFRICA - EVIDENCE FROM GHANA 1 1 1 Kwamina E. Banson+ , Nam C. Nguyen , Ockie J. H. Bosch 1. Systems Design and Complexity Management, School of Marketing and Management, University of Adelaide Business School, SA 5005 Australia ABSTRACT Over six decades, agricultural policies attempting to increase the competitiveness of project performance had limited success. This is due to the use of traditional project management methods that do not address the complex challenges encountered in a systemic way. This paper provides an example of how a systemic approach is applied to agricultural development. The findings are based on a series of workshops conducted in Ghana in 2013 and 2014. Findings include an established community development model, the “Greater Push” and a new way of measuring, monitoring and evaluating sustainable development with Bayesian Belief Network modelling that satisfies the ‘Bellagio Principles’ for measuring sustainable development indicators. This research contributes to systemic application in project management and can help policy-makers across the world to identify threats to sustainable economic growth and help them to anticipate unintended consequences of their decisions and actions before it is too late to reverse the trend. Keywords- Adaptive management; development model; economic growth; policy- makers; systems thinking; Agriculture; sustainable development; development indicators. INTRODUCTION Agriculture and its related industries are vital components not only for African but world’s developing economy (Porter, 2000). More than 90 % of Africa’s producers are small scale farmers having limited access to resources compared to their competitive counterparts in developed countries (Leichenko & O'Brien, 2002). -

Technological Capabilities and Collusion

INDUSTRIAL DEVELOPMENT AND INTERNATIONAL TRADE: TECHNOLOGICAL CAPABILITIES AND COLLUSION Leopoldo Jose Yanes Thesis submitted for the degree of Ph.D. in Economics London School of Economics September 2005 UMI Number: U61564B All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U615643 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 77 H tE |. ' /■ •'■-lyn-f 1 I / i ! British Ubm.yof ' lr«»l \ j and Economic S..*nce / C7 ° \ 5 d7 A bstract This thesis presents a theoretical analysis of industrialization. Two kinds of models are developed. The first type incorporates the following features: 1 ) Oligopolistic behaviour and strategic interaction. 2) Endogenous technological capability and market structure. 3) A general equilibrium framework. 4) A dualistic structure (characteristic of many developing countries). 5) Asymmetries in initial conditions. In part I, chapter 2 develops the benchmark model in autarky. Chapter 3 opens the econ omy. Under symmetry, trade is welfare improving. Asymmetric initial conditions imply that a backward nation may not benefit from trade with an advanced country, while the advanced nation will always benefit from trade with the backward nation. -

Economic Development As Self Discovery 7

ECONOMICS OF LESS DEVELOPED COUNTRIES EC3040b Spring 2018 Lecture 1 Michael King 1 EC3040b Economics of Less Developed Countries Course Details 1. Contact Details: [email protected] www.michaelking.ie OFFice Hours: Monday 10.30 – 12.30, Room 3002. 2. Marks For the course will be allocated as Follows: – 20% For group presentation/assignment. – 20% For essay due in Week 11. – 60% For relevant section in summer examination. 2 EC3040b Economics of Less Developed Countries Assessment 1. Group assignment (20%) – Paper Review – Personal Attendance in Tutorials (5%) – Presentation (5%) – Joint Academic Paper Review (10%) 2. Essay (20%) – topic to be announced. 3. Summer Examination (60%) 3 EC3040b Economics of Less Developed Countries Tutorials Schedule Weeks • Week 4 and 6 • Week 8, 9 and 10 • Reading week is week 7 (not lectures or tutorials) Attendance is taken and percentage awarded. Time and Room • Tutorial 1: Thursday 17.00 in Room Maxwell (Hamilton Building) • Tutorial 2: Friday 10.00 in Room 3071 4 EC3040b Economics of Less Developed Countries Understanding the Journey 5 EC3040b Economics of Less Developed Countries Course Outline 1. Contemporary Theories of Economic Development 2. Policymaking: What Role For the State in development? 3. The Role oF Institutions in Development 4. Aid: Does it work? 5. Trade: Engine oF growth or obstacle to development? 6. Domestic and International Finance: Opportunities and instability 7. Economic Growth and Environmental Sustainability 6 EC3040b Economics of Less Developed Countries Part 1: Contemporary Theories oF Economic Development 1. Historical Trends in Economic Growth 2. Review oF the Classic Theories oF Economic Growth 3. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses British political relation with Kuwait 1890-1921 Al-Khatrash, F. A. How to cite: Al-Khatrash, F. A. (1970) British political relation with Kuwait 1890-1921, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/9812/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. BRITISH POLITICAL RELATIONS WITH KUWAIT 1890-1921 . by F.A. AL-KHATRASH B.A. 'Ain Shams "Cairo" A thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Arts in the University of Durham October 1970 CONTENTS Page Preface i - iii / Chapter One General History of Kuwait from 1890-1899 1 References 32 Chapter Two International Interests in Kuwait 37 References 54 Chapter Three Turkish Relations with Kuwait 1900-1906 57 References 84 J Chapter Four British Political Relations with Kuwait 1904-1921 88 References 131 Conclusion 135 Appendix One Exclusive Agreement: The Kuwaiti sheikh and Britain 23 January 1899 139 Appendix Two British Political Representation in the Persian Gulf 1890-1921 141 Appendix Three United Kingdom*s recognition of Kuwait as an Independent State under British Protection. -

Table of Contents

Table of Contents Beacon Conference Description and Steering Committee Members………………………………………….3 Community College Sponsors, Other Sponsors…………………………………………………………………………..4 Outstanding Papers Jon Carlson The Balance of Nature and the Hunger of Children: An Ethical Exploration of Genetically Modified Organisms………………………….…….…………………5 Sarah Chan Redefining Beauty Standards: The Negative Influence of the Western Aesthetic of Thinness……………………………………………………….…………..15 Rakesh Chopde ‘Caste-ing’ Call for the Social Network: Leveling the Playing Field in India…………35 Antonio Concolino So What’s the Deal with the Value of the Renminbi Anyway?..............................53 Laura Duran Shakespeare’s Ariel and Caliban: The Others…………………………………………………….63 Erica Espinosa The Good, the Bad, and the Hope: Remittances & Globalization……………….………73 Samuel Han The End of Religion: An Epistemo-personal Exploration……………….……………………90 Adrianne Kirk Medical Miracles: The Price of Creativity? Posthumous Diagnoses of Three Great Artists…………………………………………………………………………………….104 Hannah Knowlton The Irish Potato Famine: Act of Genocide………………………………………………………..122 Diane Lameira Creating the Terrorist: The Psychology of Group Dynamics……………………………..133 1 Ryan McGrail The DeLacey Family; the True Creators of Frankenstein’s Creature………………….149 Joselida Mercado Sowing Wild Oates: Sex, Fairy Tales and Rock and Roll……………………………………157 Siomara Parada Containing the Scourge of AIDS: A Case Study on Brazil…………………………………..164 Theresa Price Kidneys Anyone?.................................................................................................182 -

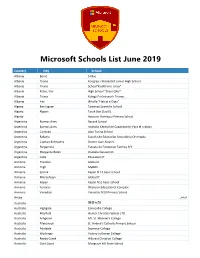

Microsoft Schools List June 2019

Microsoft Schools List June 2019 Country City School Albania Berat 5 Maj Albania Tirane Kongresi i Manastirit Junior High School Albania Tirane School"Kushtrimi i Lirise" Albania Patos, Fier High School "Zhani Ciko" Albania Tirana Kolegji Profesional i Tiranës Albania Fier Shkolla "Flatrat e Dijes" Algeria Ben Isguen Tawenza Scientific School Algeria Algiers Tarek Ben Ziad 01 Algeria Azzoune Hamlaoui Primary School Argentina Buenos Aires Bayard School Argentina Buenos Aires Instituto Central de Capacitación Para el Trabajo Argentina Cordoba Alan Turing School Argentina Rafaela Escuela de Educación Secundaria Orientada Argentina Capitan Bermudez Doctor Juan Alvarez Argentina Pergamino Escuela de Educacion Tecnica N°1 Argentina Margarita Belen Graciela Garavento Argentina Caba Educacion IT Armenia Hrazdan Global It Armenia Tegh MyBOX Armenia Syunik Kapan N 13 basic school Armenia Mikroshrjan Global IT Armenia Kapan Kapan N13 basic school Armenia Yerevan Ohanyan Educational Complex Armenia Vanadzor Vanadzor N19 Primary School الرياض Aruba Australia 坦夻易锡 Australia Highgate Concordia College Australia Mayfield Hunter Christian School LTD Australia Ashgrove Mt. St. Michael’s College Australia Ellenbrook St. Helena's Catholic Primary School Australia Adelaide Seymour College Australia Wodonga Victory Lutheran College Australia Reedy Creek Hillcrest Christian College Australia Gold Coast Musgrave Hill State School Microsoft Schools List June 2019 Country City School Australia Plainland Faith Lutheran College Australia Beaumaris Beaumaris North Primary School Australia Roxburgh Park Roxburgh Park Primary School Australia Mooloolaba Mountain Creek State High School Australia Kalamunda Kalamunda Senior High School Australia Tuggerah St. Peter's Catholic College, Tuggerah Lakes Australia Berwick Nossal High School Australia Noarlunga Downs Cardijn College Australia Ocean Grove Bellarine Secondary College Australia Carlingford Cumberland High School Australia Thornlie Thornlie Senior High School Australia Maryborough St. -

Indian Migrant Workers in West Asia Workers In

INDIAN MIGRANT WORKERS IN WEST ASIA Report on a survey of Emigrant workers in UAE and Kuwait (FINAL REPORT) B.A. Prakash Professor, RGIDS RAJIV GANDHI INSTITUTE OF DEVELOPMENT STUDIES (RGIDS) THIRUVANANTHAPURAM – 695 010 July 2014 Indian Migrant Workers in West Asia Page 1 Preface The Ministry of Overseas Indian Affairs, Government of India, has granted financial assistance to set up a Research Programme on International Migration at Rajiv Gandhi Institute of Development Studies (RGIDS), Thiruvananthapuram. The objective is to conduct research relating to various issues and problems of emigration from Kerala as well as India, to organise discussions with emigrants and return emigrants and suggest measures to improve their socio'economic conditions. As part of the Research Programme, RGIDS has conducted a study on return emigration from the West Asia and published its first report during 2013. During the second year, RGIDS conducted a research study on Indian Migrant Workers in UAE and Kuwait and prepared this report. The study has examined the profile of Indian emigrants, employment, wages and working conditions, expenditure, savings and remittances and problems of emigrants in UAE and Kuwait. For collecting primary data, we have conducted a sample survey of 200 Indian emigrant workers in UAE and 165 persons in Kuwait. The study gives an overall situation about the issues and problems of Indian emigrant workers in UAE and Kuwait. Based on the findings of the study, we have given a few recommendations. This research project has been undertaken by Prof. B.A. Prakash, Project Director of the Programme. We are grateful to Shri.