Boris Horošavin Art Historian

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Academic Communications – Promise for the Future 1 Donald G Perrin

International Journal of Instructional Technology and Distance Learning INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF INSTRUCTIONAL TECHNOLOGY AND DISTANCE LEARNING July – August - September 2018 Volume 15 Number 7–8-9 Editorial Board Donald G. Perrin Ph.D. Executive Editor Brent Muirhead Ph.D. Senior Editor Muhammad Betz, Ph.D. Editor ISSN 1550-6908 July – September 2018 i Vol. 15 No.7 - 9. International Journal of Instructional Technology and Distance Learning PUBLISHER'S DECLARATION Research and innovation in teaching and learning are prime topics for the Journal of Instructional Technology and Distance Learning (ISSN 1550-6908). The Journal was initiated in January 2004 to facilitate communication and collaboration among researchers, innovators, practitioners, and administrators of education and training involving innovative technologies and/or distance learning. The Journal is monthly, refereed, and global. Intellectual property rights are retained by the author(s) and a Creative Commons Copyright permits replication of articles and eBooks for education related purposes. Publication is managed by DonEl Learning Inc. supported by a host of volunteer editors, referees and production staff that cross national boundaries. IJITDL is committed to publish significant writings of high academic stature for worldwide distribution to stakeholders in distance learning and technology. In fourteen years, the Journal logged over fifteen million page views and more than two and one half million downloads of Acrobat files of monthly journals and eBooks. Donald G. Perrin, Executive Editor Brent Muirhead, Senior Editor Muhammad Betz, Editor July – September 2018 ii Vol. 15 No.7 - 9. International Journal of Instructional Technology and Distance Learning Vol. 15. No. 7 - 9 ISSN 1550-6908 Table of Contents – July - September 2018 Editorial: Academic communications – promise for the future 1 Donald G Perrin An instructor’s experience in using a flipped classroom with deaf 3 students: a self-study Millicent M. -

Magazines: 15 On-Line Magazines: 27

Clippings summary Serbia, Croatia and Slovenia, 30. April 2009 To date coverage received: 42 Print magazines: 15 On-line magazines: 27 Print magazines 1. Digital! Magazine, Serbia About magazine: • Monthly IT magazine • Circulation: 11.000 • Readership: • Readers: Man 16- 40 Date: 01.04.2009 1. English title: Cebit 2009 reportage 4. Mobilni Magazine, Serbia About magazine: • Monthly Lifestyle-Gadget magazine • Circulation: 10.000 • Readership: • Readers: Man 14- 55, Woman 17-35 Date: 01.04.2009 1. English title: Postcard Cebit 2009.reportage 2. English title: Win Great Prizes- Verbatim sound isolating earphones…- Quiz 2. English title: Verbatim presented new USB memories News section 6. MIKRO (PC World), Serbia About magazine: • Monthly IT magazine • Circulation: 10.000 • Readership: • Readers: Man 20-55 Date: 01.04.2009 English title: Communicative device Review- Positive 7. VIDI Magazine, Croatia About magazine: • Monthly IT magazine • Circulation: 25.000 • Readership: • Readers: Man 14- 55 Date: 01.04.2009 English title: SSD wining market Reportage- Cebit 2009- Neutral 10.BUG, Croatia About magaziBUGne: • Monthly IT magazine • Circulation: 43.000 • Readership: • Readers: Man 14- 55 Date: 01.04.2009 English title: Verbatim Store’n’Go Micro 8GB, SDHC Pro 32GB, Portable Hard Drive 500GB, USB Executive 32GB; Page: 28 Review-HARDVARE- Four short reviews- Neutraly to Positively written 12. Moj Mikro Magazine, Slovenia About magazine: • Monthly IT magazine • Circulation: 10.000 • Readership: • Readers: Man 16-60 Date: 01.04.2009 English title: Verbatim Rapier V2 Review- Neutral to Positive 6/10 13. Men’s Health Magazine, Croatia About magazine: • Monthly lifestyle magazine • Circulation: 20.000 • Readership: • Readers: Man 25-55 Date: 01.04.2009 English title: Five colors: Hard Coverage: Verbatim 2.5” external HDD 320GB; Page: 36 13. -

GSA-Report-2009.Pdf

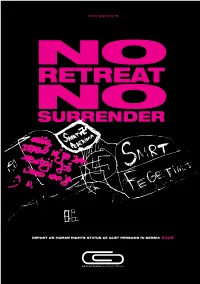

www.gsa.org.rs REPORT ON HUMAN RIGHTS STATUS OF GLBT PERSONS IN SERBIA 2009 CONTENTS PREFACE BY BORIS DITTRICH 09 OPENING WORD BY ULRIKE LUNACEK 11 I SUMMARY 13 II INTRODUCTION 15 III RIGHT TO LIFE 17 IV RIGHT TO PHYSICAL AND PSYCHOLOGICAL INTEGRITY 21 V RIGHT TO FAIR TRIAL AND EQUAL PROTECTION 33 UNDER THE LAW VI FREEDOM OF ASSEMBLY 39 VII HEALTH PROTECTION 57 VIII RIGHT TO EDUCATION 63 IX ATTITUDE OF THE STATE TOWARDS GLBT POPULATION 67 AUTHORS Boris Milićević, Nenad Sarić, Lazar Pavlović, Mirjana Bogdanović, Veroljub Đukić, Nemanja Ćirilović X THE ATTITUDE OF POLITICAL PARTIES TOWARDS 77 GLBT POPULATION TRANSLATION Ljiljana Madžarević, Vesna Gajišin, Vladimir Lazić XI THE ATTITUDE OF NATIONAL AND INTERNATIONAL 93 DIZAJN & LAYOUT ORGANIZATIONS TOWARDS GLBT POPULATION Dragan Lončar OTHER CONTRIBUTORS XII MEDIA VIEW ON GLBT POPULATION IN SERBIA 97 Miroslav Janković, Monika Lajhner, Jelena Đorđević, Dragan Popović, Zdravko Janković, Marina Marković, Jovana Zlatković, Darko Kenig, Jelisaveta Belić, Ivan Knežević, Nebojša Muljava COVER ILLUSTRATION XIII GLBT MOVEMENT IN SERBIA 99 Stylized photo of a school desk of one gay secondary school student on which are drawn swastikas, messages “death to fagots”, etc.. However, on the desk someone also wrote: “I’m glad there is someone like me. N. :)” XIV RECOMMENDATIONS 101 THANKS! Members of the Gay Straight Alliance Victims of the violence and discrimination who courageously spoke publicly and reported the incidents Civil Rights Defenders and Fund for an Open Society for financial support to create -

Yugoslav Home Computers of the 80'S

Yugoslav home computers of the 80's When the whole world started making home computers, former Yugoslavia had an import law that practically forbade import of such machines. In 1984 the first Yugoslav home computer appeared (completely open source, by today's standards) and started a revolution in home computing... Who am I... ● Passionate about old 8-,16- and 32-bit home computers (not x86 PC!) ● One of the founders of Once Uopn a Byte nonprofit organization, www.onceuponabyte.org Night of Museums Novi Sad, 2012 Night of Museums, Novi Sad, 2013 LUGoNS BarCamp 1,2 BalCCon 2013 Novi Sad More professional background... ● Linux user and promoter since 2006, member of Linux User Group of Novi Sad www.lugons.org – BalCCon, LUGoNS BarCamp ● Teaching assistant/assistant professor at Faculty of Technical Sciences, University of Novi Sad ● zzarko at lugons.org, uns.ac.rs Yugoslavia, 1956 CER-10, 1956-1960 CER-12, 1971 World, 1971-1977 1975 1974 1971 1976 1975, 8080A 1976, 6502 1977, Z80 World, 1977-1984 1982 1983 1981 Z80A 6502 Z80A 1981 1977 9900 6502 1979 6502 1981 6502 1981 1982 6502A 6510 Home computers in Yugoslavia, 1980- 1984 ● 50DM limit on import of any foreign goods ● Relatively poor domestic integrated circuit industry, no microprocessors ● Draconian import charges ● 1982: EL-82, Z80, 16kB RAM, 6000DM So, how could average person (salary) in Yugoslavia obtain a home computer? First solution... CUSTOMS Smuggling, of course! [ It's a dishwasher part... “Spectrum Superwash”... Beleive me... See, it's made of rubber, that's because of all the water... ] ...second... Legally importing foreign computers, and selling them for 2,3 or more times the price outside Yugoslavia … and finally, the third one! A vision of one man – VoJa Antonić 1983 2013 How to make an affordable computer 1. -

Building Computers in Serbia: the First Half of the Digital Century

DOI: 10.2298/CSIS110505021P Building Computers in Serbia: The First Half of the Digital Century Jelica Protić1 and Dejan Ristanović2 1 University of Belgrade, School of Electrical Engineering, Bulevar kralja Aleksandra 73 11000 Belgrade, Serbia [email protected] 2 PC Press, Osmana Đikića 4 11000 Belgrade, Serbia [email protected] Abstract. In this paper, we describe the early development of CER-10, the first digital computer built in Serbia, honor its inventors, and follow the professional path of its chief designers, prof. Rajko Tomovic and prof. Tihomir Aleksic, who became the first university professor of computer engineering in Serbia. We also give a short overview of CER family of computers that were developed after the CER-10 till mid- seventies. In the early eighties, computer revolution continued with personal computers, so we show the early attempts to produce this kind of computers in Serbia, from "build it yourself" campaigns to the industrial production, and we analyze implications of these attempts to the development of user community and evolution to the information society. Keywords: history of computing, CER family, personal computers, computer industry. 1. Introduction During the Second World War, the interest to speed up computation was driven by the need to decipher codes and to run ballistics calculations. A group of women called "human computers" were employed to use differential analyzer, a mechanical analogue computer designed to solve differential equations at The Moore School of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. But on the backstage, John W. Mauchly and J. Presper Eckert were developing ENIAC, the first computer that could perform ballistics calculations faster by a factor of 1,440. -

08/06/2019 Country Count Algeria 1 Argentina 2

Report date: 08/06/2019 Country count Algeria 1 Argentina 2 Australia 6 Austria 20 Bangladesh 1 Belgium 6 Brazil 2 Bulgaria 5 Canada 4 China 1 Croatia 10 Czech Republic 11 Denmark 11 Estonia 4 Finland 1 France 42 Germany 299 Greece 14 Hungary 9 India 4 Israel 13 Italy 96 Japan 20 Korea 1 Lithuania 1 Malta 1 Netherlands 44 Nigeria 3 Pakistan 1 Poland 31 Portugal 1 Qatar 3 Romania 8 Russia 5 Russian Federation 1 Saudi Arabia 1 Serbia 6 Serbia and Montenegro 2 Singapore 1 Slovakia 5 Slovenia 5 South Africa 3 South Korea 1 Spain 17 Sweden 13 Switzerland 11 Taiwan 1 Tunisia 1 Ukraine 6 United Arab Emirates 2 United Kingdom 69 USA 110 Vietnam 1 Publication Lastname Country #GeekTalk Hepp Germany @GillyBerlin Israel Germany 24kMedia / MacTrast Rauschnot USA 24net Papadopoulos Czech Republic 360inspiration Skalska Netherlands 9to5Mac.com / Next Media Esposito USA Abavala.com Campion France Aftonbladet Pettersson Sweden Agentur Baganz Laurent Germany Agentur Baganz Baganz Germany Agentur ET-Media Wagner Germany Agentur Queer Media Waldau Germany Al Jazeera Network Al-Banna Qatar Al Jazeera Network "Smart Lif AbdelTawab Qatar Al Jazeera Network "Smart Lif Hamideh Qatar Alt om Data Andersen Denmark andreagaleazzi.com Galeazzi Italy Android Authority Zeman USA Android Central Huseman USA AndroidAuthority.com Westenberg USA AndroidAuthority.com Rayner Germany AndroidAuthority.com Banerjee India AndroidAuthority.com Carlon USA AndroidAuthority.com Petrovan Canada AndroidAuthority.com Gordon Germany AndroidAuthority.com Imel USA AndroidAuthority.com -

Co-Financing Internet Projects .Срб .Србија & .Срб .Србија &

No 2 JULY 2010. Co-financing Internet projects RNIDS and organisations that participated in the competition signed contracts on co-financing projects at Vuk’s Foundation in Belgrade, on 21st July 2010. Out of 35 projects that applied, RNIDS will co-finance 13 projects from the field of marketing, service and Internet development and organisation of events. RNIDS will participate in co- Contracts on co-financing financing of the selected projects with more than2,800,000 RSD . signed at Vuk’s Foundation THE COMPETITION FOR CO-FINANCING PROJECTS that fulfil the basic aims of RNIDS, defined in Fund Rules and other acts of RNIDS, was published on 26th April 2010. On 1 st June the Commission selected projects from the following categories: - supporting marketing activities of registrars In Focus: - supporting development of new services and Internet popularisation - supporting organisation of expert conventions Projects of four registrars will be co-financed: -"Madnet" from Pančevo, for project REGISTRUJ.RS -"Ninet" from Niš, for the project of educating Internet users in southern Serbia -"Dream Technologies Group" from Belgrade, for promoting .RS domain as a brand -"StanCo" from Petrovac na Mlavi, for portal preduzetnici.rs, dedicated to businessmen from south-eastern Serbia The proposal for the Serbian Cyrillic IDN ccTLD: For the development of new services and Internet popularisation, financial assets will be granted to: -"Connect" from Novi Pazar, for an Internet portal for the territory of .срб& .србија Sandžak, dedicated to increasing -

Excellence in E-Content and Creativity Cairo Egypt

Excellence in e-Content and Creativity Cairo Egypt Turning the UN WSIS targets on local content into global action towards 2015 EXCELLENCE IN E-CONTENT AND CREATIVITY 2011 www.wsis-award.org WSA Strategic Under the patronage of UNESCO Partners and Sponsors United Nations Cultural Organization WSA Winners Events Hosts and Partners WSA Grand Jury Hosts and Sponsors Turning the UN WSIS targets on local content into global action towards 2015 World Summit Award Board of Directors Peter A. Bruck, Chairman, World Summit Award Alexander Felsenberg, CEOFelsenberg Consulting, Jak Boumans, Managing Director, Electronic Media CEO and Chief Researcher, Research Studios Austria Düsseldorf / Berlin, GERMANY Reporting, NETHERLANDS Forschungsgesellschaft, AUSTRIA Dorothy K. Gordon, Director-General, Ghana-India Anya Sverdlov, Managing Director, Actis Christian Rupp, Federal Executive Secretary, Kofi Annan Centre of Excellence in ICT, GHANA Wunderman, RUSSIAN FEDERATION eGovernment, Chancellery Office, AUSTRIA Osama Manzar, Founder & Director, Digital Lumko Mtimde, Chief Executive Officer, Media Catherine Warren, President, FanTrust Empowerment Foundation, INDIA Development and Diversity Agency (MDDA), Entertainment Strategies, CANADA Alfredo Ronchi, General Secretary, MEDICI SOUTH AFRICA Framework, ITALY Elizabeth Quat, Founder & Immediate Past, Reshan Dewapura , Chief Executive Officer, ICT President, Internet Professional Association (iProA), Manar Alhashash, Secretary General, Kuwait Agency of Sri Lanka (ICTA), SRI LANKA CHINA e-Award; e-Leader, UN GAID, KUWAIT Ralph Simon, CEO & Founder, Mobilium Effat El Shooky, Director of Online Distance Latif Ladid, President, IPv6 Forum, LUXEMBOURG International, Chairman Emeritus & Founder, Learning Program, Cairo Regional Center for Mobile Entertainment Forum-Americas, UNITED Rudy Laddaga Lopez Training on Conflict Resolution and Peacekeeping in KINGDOM CEO and Co-Founder, U-TOUR, MEXICO Africa -CCCPA- Cairo, EGYPT WSA e-Content & Creativity _2011 3 CAIRO, H.E. -

Central & Eastern Europe Market & Mediafact 2009 Edition

Central & Eastern Europe Market & MediaFact 2009 Edition Compiled by: Anne Austin, Nicola Hutcheon Produced by: David Parry © 2010 ZenithOptimedia All rights reserved. This publication is protected by copyright. No part of it may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without written permission from the copyright owners. ISSN 1469-6622 Every effort has been made in the preparation of this book to ensure accuracy of the contents, but the publishers and copyright owners cannot accept liability in respect of errors or omissions. Readers will appreciate that the data is only as up-to-date as printing schedules will allow and is subject to change. ZENITHOPTIMEDIA ZenithOptimedia is one of the world's leading ZenithOptimedia is committed to delivering to global media services agencies with 218 offices clients the best possible return on their in 72 countries. advertising investment. Key clients include AlcatelLucent, Beam Global This approach is supported by a unique system Spirits & Wine, British Airways, Darden for strategy development and implementation, Restaurants, Electrolux, General Mills, Giorgio The ROI Blueprint. At each stage, proprietary Armani Parfums, Kingfisher, Mars, Nestlé, ZOOM (ZenithOptimedia Optimisation of Media) L'Oréal, Puma, Polo Ralph Lauren, Qantas, tools have been designed to add value and Richemont Group, Sanofi-Aventis, Siemens, insight. Thomson Multimedia, Toyota/Lexus, Verizon, Whirlpool and Wyeth. The ZenithOptimedia -

Digital 3D Technology and Cultural Heritage: Standards and Innovations

Преглед НЦД 21 (2012), 25–33 Boris Horošavin Art historian/CG Artist DIGITAL 3D TECHNOLOGY AND CULTURAL HERITAGE: STANDARDS AND INNOVATIONS Abstract: In recent years cultural heritage practice has overtaken decisive steps towards new digital technolo- gies. Various projects have been conducted in our region employing these new methods. The efficiency and utility of digital 3D technology has been proved beyond any doubt, especially considering its multipurpose char- acter. Its implementation can be multifarious, ranging from digital scanning and documenting an object to creat- ing elaborate 3D visualizations as a vital part of conservation project documentation. However, conservation and restoration practice in our region isn’t yet fully in tune with rapid techno- logical development. Basic technical documentation for many significant objects is still kept in hand drawn or analogue form and concomitant photo-material is old, inadequate and practically unusable. There is a strong need for closer connection between traditional documenting, conservation and restoration processes and techni- cal innovations. These are the main questions this article will try to answer: How to gather and process data in a manner compatible with digital techniques? What are new tools and methods in recording and documenting ma- terial? What are the benefits and advantages of implementing 3D and overall digital technology in conservation and restoration procedures? Keywords: Cultural heritage, Digitalization, 3D technology, Architecture, Archeology 1. Introduction -

Kompjuteri Blog ~ Zbornik IT Tekstova Sa Bloga Kompjuteri ~

Darth Ewok & Windu Jet Kompjuteri Blog ~ Zbornik IT tekstova sa bloga Kompjuteri ~ ©2014 Kompjuteri Blog Tim, pod uslovima CC-BY-SA O blogu Kompjuteri - Opste kompjuterske teme. Pitanja i odgovori, pomoc korisnicima, igre, emulatori, operativni sistemi, grafika, programiranje, internet... - Prvobitno je postojao klub Kompjuteri na nekadasnjem sajtu Urbae, ali je zbog reorganizacije sajta i promene dizajna i funkcionalnosti, klub Kompjuteri morao biti zatvoren, jer, novonastale promene umesto da poboljsaju funkcionalnost klubova, samo su upropastile do tada solidnu platformu za funkcionisanje klubova. - Zatim je osnovana grupa Kompjuteri na Fejsbuku, koja je takodje zatvorena zbog prelaska na novi format grupa, za koji tvrde da donosi poboljsanja, ali umesto poboljsanja, funkcionalnost grupa je upropastena. - Zbog toga sam otvorio ovaj blog na WordPressu. Nadam se da WordPress nece, kao i Urbae i Fejsbuk, nekim nazovi poboljsanjima upropastiti funkcionalnost bloga. ---------------------------------------------------- - Saveti, programi i internet adrese koje sam pomenuo u blogu su provereni i bezbedni. Ne odgovaram za bilo kakvu eventualnu stetu nastalu koriscenjem saveta, programa i ostalih stvari pomenutih u blogu. Jer, kao sto napisah, sve je probano i provereno, tako da ako nesto nije u redu, znaci da nesto niste dobro odradili. - Internet adrese i linkovi prema drugim sajtovima koji se pominju u tekstovima, su provereni u vreme pisanja samih tekstova. S obzirom da su mnogi tekstovi stari i vise od godinu dana, moze se desiti da su neke adrese u medjuvremenu promenjene, pa samim tim i ti linkovi nece raditi. Ako primetite da neka adresa prema drugom sajtu vise nije aktuelna, slobodno ostavite komentar. Ja cu u najkracem mogucem roku to ispraviti. ~ Darth Ewok O ovoj knjizi Ebook je nastao sa idejom da se citaocima da lep i koristan poklon povodom Nove godine. -

Child Labour in the Republic of Serbia

MEDIA REPORTING ON CHILD LABOUR IN THE REPUBLIC OF SERBIA Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work Branch (FUNDAMENTALS) International Labour Organization (ILO) Copyright © International Labour Organization 2018 First published 2018 Publications of the International Labour Office enjoy copyright under Protocol 2 of the Universal Copyright Convention. Nevertheless, short excerpts from them may be reproduced without authorization, on condition that the source is indicated. For rights of reproduction or translation, application should be made to ILO Publications (Rights and Licensing), International Labour Office, CH-1211 Geneva 22, Switzerland, or by email: [email protected]. The International Labour Office welcomes such applications. Libraries, institutions and other users registered with a reproduction rights organization may make copies in accordance with the licences issued to them for this purpose. Visit www.ifrro.org to find the reproduction rights organization in your country. FUNDAMENTALS Media reporting on child labour in the Republic of Serbia, International Labour Office, Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work Branch (FUNDAMENTALS), Geneva: ILO, 2018. ISBN: 978-92-2-132173-6 (Print); 978-92-2-132174-3 (Web PDF) International Labour Office; ILO Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work Branch Also available in Serbian: Izveštavanje medija o zloupotrebi dečjeg rada u Republici Srbiji, ISBN: 978-92-2-132175-0 (Print); 978-92-2-132176-7 (Web PDF), Geneva, 2018. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Funding for this ILO publication is provided by the United States Department of Labor (USDOL) under cooperative agreement number IL-24943-13-75-K of the Project “Country Level Engagement and Assistance to Reduce Child Labour (CLEAR)” (GLO/13/22/USA). This publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the United States Department of Labor, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the United States Government.