Cadden-Et-Al2018.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Death Studies )

JNDAE7 20(4) 211-286 (2002) ISSN 0891-4494 http://www.wkap.n1/journalhome.htm/O89 1-4494 Journal of I Lear -Death Studies ) s Editor's Foreword " Bruce Greyson, M.D. A Prospective Analysis of Near-Death Experiences in Cardiac Arrest Patients " Janet Schwaninger, R.N., B.S.N., Paul R. Eisenberg, M.D., M.P.H., Kenneth B. Schechtman, Ph.D., and Alan N. Weiss, M.D., FA.C.C. The Evidential Value of Near-Death Experiences for Belief in Life After Death " Michael Potts, Ph.D. Book Reviews: The Final Entrance: Journeys Beyond Life, by Susan L. Schoenbeck " Reviewed by Dianne Arcangel, M.S. Cosmic Cradle: Souls Waiting in the Wings for Birth, by Elizabeth M. Carman and Neil J. Carman e Reviewed by David B. Chamberlain, Ph.D. Letters to the Editor " P M. H. Atwater, L. H. D., and Harold A. Widdison, Ph.D. Volume 20, Number 4, Summer 2002 www.iands.org Journal of Near-Death Studies EDITOR Bruce Greyson, M.D., University of Virginia, Charlottesville, Virginia CONSULTING EDITORS James E. Alcock, Ph.D., C.Psych., York University, Toronto, Ontario, Canada Carlos Alvarado, Ph.D., Parapsychology Foundation, New York, New York J. Kenneth Arnette, Ph.D., Eastern Washington University, Cheney, Washington Boyce Batey, Academy of Religion and Psychical Research, Bloomfield, Connecticut Carl B. Becker, Ph.D., Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan Paul Bernstein, Ph.D., Institute for Psychological and Spiritual Development, Cambridge, Massachusetts Diane K. Corcoran, R.N., Ph.D., Senior University, Richmond, British Columbia, Canada Elizabeth W. Fenske, Ph.D., Spiritual Frontiers Fellowship International, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania John C. -

Team-Fly® Power up Your Mind

Power Up Your Mind:Y L Learn faster,F work smarterM A E T Bill Lucas NICHOLAS BREALEY PUBLISHING Team-Fly® Power Up Your Mind Learn faster, work smarter Bill Lucas N ICHOLAS B REALEY P UBLISHING LONDON First published by Nicholas Brealey Publishing in 2001 Reprinted (twice) 2002 3–5 Spafield Street PO Box 700 Clerkenwell, London Yarmouth EC1R 4QB, UK Maine 04096, USA Tel: +44 (0)20 7239 0360 Tel: (888) BREALEY Fax: +44 (0)20 7239 0370 Fax: (207) 846 5181 http://www.nbrealey-books.com http://www.powerupyourmind.com © Bill Lucas 2001 The right of Bill Lucas to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. ISBN 1-85788-275-X British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Lucas, Bill. Power up your mind : learn faster, work smarter / Bill Lucas. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1-85788-275-X 1. Learning, Psychology of. 2. Work--Psychological aspects. I. Title. BF318 .L83 2001 153.1′5--dc21 2001035940 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording and/or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publishers. This book may not be lent, resold, hired out or otherwise disposed of by way of trade in any form, binding or cover other than that in which it is published, without the prior consent of the publishers. -

Truly Transformative: Assessing the Impacts of Learning Focused Intention Technique®

TRULY TRANSFORMATIVE: ASSESSING THE IMPACTS OF LEARNING FOCUSED INTENTION TECHNIQUE® By KATHERINE BIRD Integrated Studies Project submitted to Reinekke Lengelle in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts – Integrated Studies Athabasca, Alberta March, 2012 Truly Transformative Assessing the impacts of learning Focused Intention Technique Katherine Bird Table of Contents Abstract 1 Introduction 2 Defining Formal and Non-formal Education 4 Theoretical Background 7 The transformative education perspective 8 The feminist perspective 11 The Question of Legitimacy 13 The Training 17 The Research Project 36 The research intention 36 The method 38 The results 40 Conclusion 56 Sources 60 Appendix 1 66 Appendix 2 67 i Truly Transformative Assessing the impacts of learning Focused Intention Technique Katherine Bird List of Figures Figure 1 The Whole Self Model 21 Figure 2 Participant Demographics 40 Figure 3a Stated Issues: Physical/Health 42 Figure 3b Stated Issues: Physical/Social/Environment 44 Figure 3c Stated Issues: Spiritual/Belief 45 Figure 3d Stated Issues: Mental/cognitive 46 Figure 3e Stated Issues: Emotional 47 Figure 4 Holistic Assessment Part 1: Mean Scores 48 Figure 5 Holistic Assessment Part 2: Participant Totals 50 Figure 6 Holistic Assessment Part 2: Mean Scores 51 Figure 7 Percentage Reduction Totals 52 Figure 8 HRV Score Comparisons 53 ii Truly Transformative Assessing the impacts of learning Focused Intention Technique Katherine Bird Abstract Throughout North America there are scores of well-attended programs training participants to apply alternative/complementary health approaches for their own or professional use. While the exclusive influence of the medical discipline is beginning to accept that patients are seeking alternative roads to mental and emotional healing, empirical evidence remains the crux of formal recognition by mainstream health systems. -

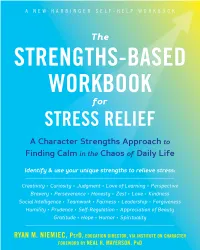

The Strengths-Based Workbook for Stress Relief, Niemiec Shows How Your Strengths Can Be a Resource Both for Joy and Resilience

“In The Strengths-Based Workbook for Stress Relief, Niemiec shows how your strengths can be a resource both for joy and resilience. This workbook will help readers craft a more meaningful and rewarding life, whether they are seeking to amplify what’s good in their lives or find a way through difficult times.” —Kelly McGonigal, PhD, author of The Upside of Stress and The Willpower Instinct “I’ve worked for decades at the intersection of mind-body health, healing, and stress management. Ryan Niemiec’s book championing the use of character strengths to manage stress is a milestone in mind-body wellness, the first of its kind. It offers a template for shifting how you think about and handle your daily stress. This book is a well-being booster, a resilience enhancer, and a stress manager all in one! At the least, you’ll be freshly empowered to handle your future stressors; and at best, you’ll transform your life while uplifting those around you.” —Joan Borysenko, PhD, New York Times bestselling author of Minding the Body, Mending the Mind “In this groundbreaking workbook, Ryan Niemiec takes the reader on a journey of discovery, pro- viding help in identifying their stress and character strengths. This process is linked to a range of excellent tools to tackle stress. At the end of each chapter the Learn, Practice, SHARE section assists in embedding what has been learned. This easy-to-read, positive psychology–informed book takes a self-coaching approach and promotes personal growth and development. This book could possibly change your life.” —Stephen Palmer PhD, professor of practice at the Wales Institute for Work-Based Learning at the University of Wales Trinity Saint David, founder and director of the Centre for Stress Management, and coauthor of How to Deal with Stress “This book is a breakthrough addition to the field of health and wellness. -

Qalb E Saleem (Pure Heart) and Qalb E Mareez (Diseased Heart): Insight from Scriptures and Medical Science

Central Journal of Cardiology & Clinical Research Review Article *Corresponding author Iqbal Akhtar Khan, Independent Scholar, Lahore-54792, Pakistan, Email: [email protected] Qalb e Saleem (Pure Heart) Submitted: 30 January 2021 Accepted: 26 February 2021 and Qalb e Mareez (Diseased Published: 28 February 2021 ISSN: 2373-9312 Copyright Heart): Insight from Scriptures © 2021 Khan IA, et al. OPEN ACCESS and Medical Science Keywords • Qalb e Saleem Iqbal Akhtar Khan1* and Hamza Iltaf Malik2 • Qalb e Mareez • Healthy heart 1Independent Scholar, Pakistan • Diseased heart 2 Northampton General Hospital, UK • Brain in the heart Abstract Human heart, “a wondrous magic casket”, has been believed to be the seat of intelligence, emotion and sensation in ancient scriptures and non-Abrahamic religions. According to monotheistic religions, it has psychological, moral and spiritual functions. It could either be healthy or diseased. The modern scientific research has proved that an emotional brain is formed long before a rational one, and the heart has its own independent complex nervous system known as ‘the brain in the heart.’ The heart sends out electromagnetic field which controls our emotions. Whereas the theory of cellular memories states that memories, as well as personality traits, are not only stored in the brain but may also be stored in organs such as the heart, it has been reported that the heart transplant recipients seem to be the most susceptible to significant changes in personality, the possible mechanism being the transfer of memory through heart. The heart also manufactures and secretes oxytocin, referred as “love or social-bonding hormone”. Moreover, its role in cognition, tolerance, trust and friendship and the establishment of enduring pair-bonds has been well recognized. -

The Author Has Granted an Irrevocable Non-Exclusive

Narotmi uurary trialorneque riaiuMW of Canada du Canada Acquisitions and Direclion des acquisitions et Biùiiographii Services Branch des seMces bibliographiques THE AUTHOR HAS GRANTED AN L'AUTEUR A ACCORDE UNE LICENCE IRREVOCABLE NON-EXCLUSIVE iRREVOCABLE ET NON EXCLUSIVE LICENCE ALLOWMG THE NATIONAL PERMETTANT A LA BIBLIOTHEQUE LIBRARY OF CANADA TO NATIONALE DU CANADA DE REPRODUCE, LOAN, DISTRIBUTE OR RE:PRODüIRE, PRETER, DISTRIBUER SELL COPIES OF HISEIER THESIS BY OU VENDRE DES COPIES DE SA ANY MEANS AND IN ANY FORM OR THESE DE QUELQUL MAWIERE ET FORMBT, MAKING THIS THESIS SOUS QUELQUE FORME QUE CE SOU AVAILABLE TO INTEPESTED POUR METTRE DES EXEMPLAIRES DE PERSONS. CETTE THESE A LA DISPOSïïION DES PERSONNE INTERESSEES. THE AUTHOR RETAINS OWNERSHIE' L'AUTEUR CONSERVE LA PROPRETE OF THE COPYRIGHT M HISMER DU DROIT D'AUTEUR QUI PROTEGE THESIS. NEITHER THE THESIS NOR SA THESE. NI LA THESE NI DES SUBSTANTIAL EXTRACTS FROM IT EXTRAirrS SUBSTANTIELS DE CELLE- MAY BE PRINTED OR OTHERWISE CI .NE DONENT ETRE IMPRIMES OU REPRODUCED WITHOUT HIS/HER AUTREMENT REPRODUITS SANS SON PERMISSION. AUTORISATION. ISBN 0-612-01998-5 Nom \n&d\ny' A cd c. r%ln ~irse&'on Abstracts ~nierndondis arracged by brwd. general subiect categories . Please select the one svbiect which most mrlydescribes ths content of ywr dissertation. Enter the corresponding four-digit code in the spoces provided. n~tcAT (\ ldGTE4 UMI SUBJM CODE SUIIIM TERM Subject Categories 1111 HUMANlTllS AND SOCIAL SCIENCES PHILOSOPHY. RELIGION AND Ancient ..............................0579 COMMUWICAIIOHS MDTHE ARTS Psycholqy ...............................0525 Mediwol ...........................0581 ArchiWre ..............................0729 Raoding ..................................0535 THEOLOGY Modern ............................0582 ~r(Hisw ..................... ...... 0377 ibligiws ..................................0527 Phil-hy ........... -

The Interviews

Jeff Schechtman Interviews December 1995 to April 2017 2017 Marcus du Soutay 4/10/17 Mark Zupan Inside Job: How Government Insiders Subvert the Public Interest 4/6/17 Johnathan Letham More Alive and Less Lonely: On Books and Writers 4/6/17 Ali Almossawi Bad Choices: How Algorithms Can Help You Think Smarter and Live Happier 4/5/17 Steven Vladick Prof. of Law at UT Austin 3/31/17 Nick Middleton An Atals of Countries that Don’t Exist 3/30/16 Hope Jahren Lab Girl 3/28/17 Mary Otto Theeth: The Story of Beauty, Inequality and the Struggle for Oral Health 3/28/17 Lawrence Weschler Waves Passing in the Night: Walter Murch in the Land of the Astrophysicists 3/28/17 Mark Olshaker Deadliest Enemy: Our War Against Killer Germs 3/24/17 Geoffrey Stone Sex and Constitution 3/24/17 Bill Hayes Insomniac City: New York, Oliver and Me 3/21/17 Basharat Peer A Question of Order: India, Turkey and the Return of the Strongmen 3/21/17 Cass Sunstein #Republic: Divided Democracy in the Age of Social Media 3/17/17 Glenn Frankel High Noon: The Hollywood Blacklist and the Making of an American Classic 3/15/17 Sloman & Fernbach The Knowledge Illusion: Why We Think Alone 3/15/17 Subir Chowdhury The Difference: When Good Enough Isn’t Enough 3/14/17 Peter Moskowitz How To Kill A City: Gentrification, Inequality and the Fight for the Neighborhood 3/14/17 Bruce Cannon Gibney A Generation of Sociopaths: How the Baby Boomers Betrayed America 3/10/17 Pam Jenoff The Orphan's Tale: A Novel 3/10/17 L.A. -

Pdf/44/5/255/39702/4447499.Pdf by Guest on 29 September 2021

The Anmerican BIOLOGYTEACHER MAY 1982 * VOLUME 44, NUMBER 5 Downloaded from http://online.ucpress.edu/abt/article-pdf/44/5/255/39702/4447499.pdf by guest on 29 September 2021 I g 'S~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~-W, t :;00;L00V:;fu:t Top quality materials from a name you can trust... Carolina's b Natural Bone Skeletons Downloaded from http://online.ucpress.edu/abt/article-pdf/44/5/255/39702/4447499.pdf by guest on 29 September 2021 Carolina has led in supplying educators with quality scientific materials for over 50 years. Every, order we ship is backed with unsurpassed service and care from a skilled staff. and human skeleton " materials are no exception. We have AKi.. 3 an extensive of the finest inventory w - * natural bone and plastic specimens. f s0.'0 and like every product we sell, each is OK unconditionally guaranteed. Order .4/0 f - from a name you can trust order frorn Carolina. Write LiS and we'll send you a free. fUll-color comprehensive catalog of Carolina natural bone and plastic skeletons. Carolina Biological > SuoPlu ComPany IIA oI 2700 York Road ? ?' \_ Burlington, North Carolina 27215 X /_ Box 187 wa r Gladstone, Oregon 97027 #& 4 p I You can lose PERMANENT your valuable eAIRTIGHT biological and SPECIMEN geological collections PRESERVATION through with *~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ Improper storage! SCIENCECABINETS Downloaded from http://online.ucpress.edu/abt/article-pdf/44/5/255/39702/4447499.pdf by guest on 29 September 2021 l ~ - g.> . iifff:000-i .. I. ............... BOTANY SPECIMEN ENTOMOLOGY ZOOLOGY-ORNITHOLOGY GEOLOGY-PALEONTOLOGY CABINETS SPECIMEN CABINETS SPECIMEN CABINETS SPECIMEN CABINETS * I LaneScience Equipment Corp. -

PAUL PEARSALL, Ph.D

The Heart s Qode Othar Books by Paul Paarsall, Ph.D. Superimmunity: Master Your Emotions and Improve Your Health Super Marital Sex: Loving for Life Super Joy: Learning to Celebrate Everyday Life The Power of the Family: Strength, Comfort, and Healing Making Miracles The Ten Laws of Lasting Love A Healing Intimacy: The Power of Loving Connections The Pleasure Prescription: To Love, To Work, To Play—Life in the Balance Write Your Own Pleasure Prescription: 60 Ways to Create Balance and Joy in Your Life PAUL PEARSALL, Ph.D. The \ Tapping the Wisdom and Power of Our Heart Energy The New Findings About Cellular Memories and Their Role in the Mind / Body / Spirit Connection BROADWAY BOOKS NEW YORK BROADWAY A hardcover edition of this book was published in 1998 by Broadway Books. THE HEART'S CODE. Copyright ® 1998 by Paul Pearsall. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of Amer- ica. No pan of this book may be reproduced or transmit- ted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher. For information, address Broadway Books, a division of Random House, Inc., 1740 Broadway, New Yoik, NY 10036. Broadway Books tides may be purchased for business or promotional use or for special sales. For information, please write to: Special Markets Department, Random House, Inc., 1540 Broadway, New York, NY 10036. BROADWAY BOOKS and its logo, a letter B bisected on the diagonal, are trademarks of Broadway Books, a division of Random House, Inc. -

Water and People: Challenges at the Interface of Symbolic and Utilitarian Values

United States Department of Water and People: Challenges Agriculture Forest Service at the Interface of Symbolic Pacific Northwest and Utilitarian Values Research Station General Technical Report PNW-GTR-729 January 2008 The Forest Service of the U.S. Department of Agriculture is dedicated to the principle of multiple use management of the Nation’s forest resources for sus- tained yields of wood, water, forage, wildlife, and recreation. Through forestry research, cooperation with the States and private forest owners, and manage- ment of the national forests and national grasslands, it strives—as directed by Congress—to provide increasingly greater service to a growing Nation. The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability, and where applicable, sex, marital status, familial status, parental status, religion, sexual orientation, genetic information, political beliefs, reprisal, or because all or part of an individual’s income is derived from any public assistance program. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination write USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, 1400 Independence Avenue, S.W. Washington, DC 20250-9410, or call (800) 795- 3272 (voice) or (202) 720-6382 (TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. Editors Stephen F. McCool was a professor (now retired) of Wildland Recreation Manage- ment, College of Forestry, University of Montana, Missoula, MT 59812. -

PSYCHOLOGY Copy.Pages

QUOTES ON PSYCHOLOGY ! ! Mental health problems do not affect three or four out of every five persons but one out of one. ! --Dr. William Menninger Human beings are not perfectible. They are improvable. ! --Eric Sevareid When you look directly at an insane man, all you see is a reflection of your own knowledge that he’s insane, which is not to see him at all. To see him you must see what he saw. ! --Robert Pirsig We can escape from the level of society, but not from the level of intelligence to which we were born. ! --Randall Jarrell All human activity is prompted by desire. ! --Bertrand Russell Psychology is the science of mental life. ! —William James We see the world, not as it is, but as we are -- or, as we are conditioned to see it. When we open our mouths to describe what we see, we in effect describe ourselves, our perceptions, our paradigms. ! —Stephen R. Covey The childhood shows the man As morning shows the day. ! --John Milton Woman’s basic fear is that she will lose love. ! --Sigmund Freud Men are what their mother made them. --Ralph Waldo Emerson ! - !1 - Man is a wanting animal--as soon as one of his needs is satisfied, another appears in its place. This process is unending. It continues from birth to death. ! --Douglas McGregor There is no one on this earth who is not twisted by fear and insecurity. ! --Doris Lessing Depression is the inability to construct a future. ! --Rollo May Schizophrenic behaviour is a special strategy that a person invents in order to live in an unlivable situation. -

What Have They Told Us About Gangs? a Content Analysis of Twentieth Century Texts on U.S. Gangs

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Dissertations Graduate College 6-2002 What Have They Told Us About Gangs? A Content Analysis of Twentieth Century Texts on U.S. Gangs Douglas Lee Gilbertson Western Michigan University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations Part of the Social Control, Law, Crime, and Deviance Commons, and the Sociology of Culture Commons Recommended Citation Gilbertson, Douglas Lee, "What Have They Told Us About Gangs? A Content Analysis of Twentieth Century Texts on U.S. Gangs" (2002). Dissertations. 1227. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations/1227 This Dissertation-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WHAT HAVE THEY TOLD US ABOUT GANGS? A CONTENT ANALYSIS OF TWENTIETH CENTURY TEXTS ON U.S. GANGS by Douglas Lee Gilbertson A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Sociology Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan June 2002 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. WHAT HAVE THEY TOLD US ABOUT GANGS? A CONTENT ANALYSIS OF TWENTIETH CENTURY TEXTS ON U.S. GANGS Douglas Lee Gilbertson, Ph.D. Western Michigan University, 2002 Inspired by a scholarly desire to understand and explain things, formal theoretical explanations for the social problem of gangs have been around just about as long as gangs themselves.