Edinburgh Research Explorer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Humanoid Robots (Figures 41, 42)

A Roboethics Framework for the Development and Introduction of Social Assistive Robots in Elderly Care Antonio M. M. C. Espingardeiro Salford Business School University of Salford, Manchester, UK Submitted in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy, September 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter 1 - Introduction ......................................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter 2 - Literature review ................................................................................................................................. 9 2.1. Ethics in the digital world ................................................................................................................................ 9 2.2. Exploratory work in roboethics ..................................................................................................................... 14 2.2. Roboethics rules and guidance ...................................................................................................................... 18 2.3. “In-situ” practical workshops with SARs ........................................................................................................ 23 2.4. Summary ........................................................................................................................................................ 24 Chapter 3 - Human robotics interactions and ethical principles ......................................................................... -

Robotic Art and Cultural Imagination

http://dx.doi.org/10.14236/ewic/EVAC18.48 Robotic Art and Cultural Imagination Bojana Romic School of Arts and Communication Nordenskiöldsgatan 1, 211 19 Malmö, Sweden [email protected] In this article, I aim to accentuate the importance of the cultural imagination about robots, observing it 'as a mixed register of fantasy and an actual practice' (Kakoudaki 2007, 165). I emphasise the field of robotic art, which, I argue, is in a fluid state of exchange with other areas of robotic research, equally benefiting from the larger context of the cultural imagination about robots. Furthermore, I discuss artworks that offer a valuable commentary on robots even though they are not defined as robotic art in a narrow sense (Penny 2013), given that they feature only the representation of robots or robot-like characters. Nevertheless, these artworks contribute to the circulation of symbolic registers that revolve around the multifaceted figure of a robot. Robot. Robotic Art. Cultural imagination. Cultural robotics. 1. INTRODUCTION imagination: I do not probe deeper into ideological, religious and societal reasons for imaginaries that In recent years, there has been an ongoing debate are characteristic of particular societies (e.g. about the notion and (possible) function of robotic Japanese, US, Korean, etc.). Instead, I focus on culture. With the development of the new generation phenomenological aspects of cultural imagination in of drones, as well as the advancement in social and robotic art in general. health robotics, questions about the robot culture seem to open a variety of discussions (Kim & Kim 2013, Samani et al. 2013, Šabanović et al. -

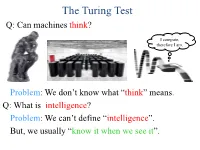

The Turing Test Q: Can Machines Think?

The Turing Test Q: Can machines think? I compute, therefore I am. Problem: We don’t know what ―think‖ means. Q: What is intelligence? Problem: We can’t define ―intelligence‖. But, we usually ―know it when we see it‖. The Turing Test Q: Which of the following can think? The Turing Test Q: Can you distinguish a machine from a person? ≡ Can a machine impersonate a person? The Turing Test • The first deep investigation into whether machines can ―behave intelligently‖ • Helped usher in field of AI • Decoupled ―intelligence‖ from ―human‖ • Based ―intelligence‖ on I/O, not entity’s ―look and feel‖ • Proposed a practical, formal test for intelligence • Definitions & test are operational & easily implementable • Turing test variants: ―immortality‖, ―fly-on-wall‖, ―meta‖, ―reverse‖, ―subject matter expert‖, ―compression‖, ―minimum intelligent signal‖ Turing Test Milestones Turk (von Kempelen), 1770: • Played a strong game of chess • Toured the world for 84 years • Generated much interest in automata • Was a hoax (hidden human operator) Turing Test Milestones Eliza (Weizenbaum), 1966: • First ―chatterbot‖ • Named after ―Eliza Doolittle‖ of Shaw’s Pygmalion • Simulated Rogerian psychotherapist • Often convinced people it is human • Influence computer games (e.g., Dungeon, Adventure) • Inspired Arthur C. Clarke’s HAL 9000 • Chatterbots appear today in chatrooms and dating services • Chatterbot competitions (Turing Test format): – Loebner Prize – Chatterbox Challenge, 2010 Turing Test Milestones Elbot, 2008: • Won 2008 Loebner Prize • Fooled 3 of 12 judges (Turing: >30%) • Typical excerpt: Judge: What's your favourite novel? Elbot: I often read telephone books, or dadaist poetry: Brä brä brä Judge: Typical computer! Elbot: You tend towards generalizations. -

Sensorimotor Control of Octopus-Inspired Soft Robots

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2013 Learning from the octopus: sensorimotor control of octopus-inspired soft robots Li, Tao Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich ZORA URL: https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-91630 Dissertation Published Version Originally published at: Li, Tao. Learning from the octopus: sensorimotor control of octopus-inspired soft robots. 2013, University of Zurich, Faculty of Economics. Department of Informatics Learning from the Octopus: Sensorimotor Control of Octopus-Inspired Soft Robots A dissertation submitted to the Faculty of Economics, Business Administration and Information Technology of the University of Zurich for the degree of Doctor of Science (Ph.D.) by Tao Li from China Accepted on the recommendation of Prof. Dr. Rolf Pfeifer Prof. Akio Ishiguro, Ph.D. 2013 The Faculty of Economics, Business Administration and Information Technol- ogy of the University of Zurich herewith permits the publication of the afore- mentioned dissertation without expressing any opinion on the views contained therein. Zurich, October 23, 2013 Head of the Ph.D. committee for informatics: Prof. Abraham Bernstein, Ph.D Abstract Soft robotics is one of the most promising, yet challenging, research topics in bio-inspired robotics. In terms of morphological and behavioral flexibility as well as interaction safety, soft robots have significant advantages over traditional articulated rigid robots. However, it is difficult to achieve autonomous sensorimotor control of a soft robot by conventional engineering approaches primar- ily because of its complex nonlinear soft body dynamics. Most soft robots are currently controlled only in an open-loop scheme. -

The Perception and Measurement of Human-Robot Trust

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2013 The Perception And Measurement Of Human-robot Trust Kristin Schaefer University of Central Florida Part of the Psychology Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Doctoral Dissertation (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Schaefer, Kristin, "The Perception And Measurement Of Human-robot Trust" (2013). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 2688. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/2688 THE PERCEPTION AND MEASUREMENT OF HUMAN-ROBOT TRUST by KRISTIN E. SCHAEFER B. A. Susquehanna University, 2003 M. S. University of Central Florida, 2009 A dissertation submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Modeling and Simulation in the College of Sciences at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Summer Term 2013 Major Professor: Peter A. Hancock © 2013 Kristin E. Schaefer ii ABSTRACT As robots penetrate further into the everyday environments, trust in these robots becomes a crucial issue. The purpose of this work was to create and validate a reliable scale that could measure changes in an individual’s trust in a robot. Assessment of current trust theory identified measurable antecedents specific to the human, the robot, and the environment. Six experiments subsumed the development of the 40 item trust scale. -

Writing a Moral Code: Algorithms for Ethical Reasoning by Humans and Machines

religions Article Writing a Moral Code: Algorithms for Ethical Reasoning by Humans and Machines James McGrath 1,* ID and Ankur Gupta 2 1 Butler University, Department of Philosophy, Religion, and Classics, 4600 Sunset Avenue, Indianapolis, IN 46208, USA 2 Butler University, Department of Computer Science, 600 Sunset Avenue, Indianapolis, IN 46208, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-317-940-9364 Received: 31 July 2018; Accepted: 7 August 2018; Published: 9 August 2018 Abstract: The moral and ethical challenges of living in community pertain not only to the intersection of human beings one with another, but also our interactions with our machine creations. This article explores the philosophical and theological framework for reasoning and decision-making through the lens of science fiction, religion, and artificial intelligence (both real and imagined). In comparing the programming of autonomous machines with human ethical deliberation, we discover that both depend on a concrete ordering of priorities derived from a clearly defined value system. Keywords: ethics; Isaac Asimov; Jesus; Confucius; Socrates; Euthyphro; commandments; robots; artificial intelligence; programming; driverless cars 1. Introduction Ethical reasoning, when it is done effectively, involves prioritizing between competing options. Philosophical thought experiments such as the “trolley problem” highlight the human tendency to avoid making decisions about situations in which there is no good outcome. However, the history of both religion -

Socially Believable Robots Socially Believable Robots

DOI: 10.5772/intechopen.71375 Chapter 1 Provisional chapter Socially Believable Robots Socially Believable Robots Momina Moetesum and Imran Siddiqi Momina Moetesum and Imran Siddiqi Additional information is available at the end of the chapter Additional information is available at the end of the chapter http://dx.doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.71375 Abstract Long-term companionship, emotional attachment and realistic interaction with robots have always been the ultimate sign of technological advancement projected by sci-fi literature and entertainment industry. With the advent of artificial intelligence, we have indeed stepped into an era of socially believable robots or humanoids. Affective com- puting has enabled the deployment of emotional or social robots to a certain level in social settings like informatics, customer services and health care. Nevertheless, social believability of a robot is communicated through its physical embodiment and natural expressiveness. With each passing year, innovations in chemical and mechanical engi- neering have facilitated life-like embodiments of robotics; however, still much work is required for developing a “social intelligence” in a robot in order to maintain the illusion of dealing with a real human being. This chapter is a collection of research studies on the modeling of complex autonomous systems. It will further shed light on how different social settings require different levels of social intelligence and what are the implications of integrating a socially and emotionally believable machine in a society driven by behaviors and actions. Keywords: social robots, human computer interaction, social intelligence, cognitive systems, anthropomorphism, humanoids, roboethics 1. Introduction Robots have been an important part of the industrial setups around the globe for many years now. -

From Cybermen to the TARDIS: How the Robots of Doctor Who Portray a Nuanced View of Humans and Technology

From Cybermen to the TARDIS: How the Robots of Doctor Who Portray a Nuanced View of Humans and Technology GWENDELYN S. NISBETT AND NEWLY PAUL Critics and fans have praised the 2000s reboot of the science fiction classic Doctor Who for its increasing use of social commentary and politically relevant narratives. The show features the adventures of the Doctor and his companions, who have historically been humans, other aliens, and occasionally robots. They travel through time and space on a spaceship called the TARDIS (which is shaped like a 1960s British police box). The show is meant for younger audiences, but the episodes involve political and social commentary on a range of issues, such as racism, sexism, war, degradation of the environment, and colonialism. The Doctor is an alien from Gallifrey and can (and does) regenerate into new versions of the Doctor. Scholars have commented extensively about the show in the context of gender and race, political messaging, transmedia storytelling, and fandom. In this project, we examine the portrayal of robots and labor, a topic that is underexplored in relation to this show. Doctor Who makes for an interesting pop culture case study because, though the show has a huge global fan base, its heart remains in children’s programming. The series originated in 1963 on the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) as a show for children that incorporates lessons related to courage, ingenuity, kindness, and other such qualities, which it continues to do to this day. Doctor Who is also interesting because the Doctor has a history of machines as companions: K-9 the GWENDELYN S. -

Machine Ethics and Robot Ethics the Library of Essays on the Ethics of Emerging Technologies

MACHINE ETHICS AND ROBOT ETHICS THE LIBRARY OF ESSAYS ON THE ETHICS OF EMERGING TECHNOLOGIES Series editor: Wendell Wallach Titles in the series The Ethical Challenges of Emerging Medical Technologies Edited by Arthur L. Caplan and Brendan Parent The Ethics of Biotechnology Edited by Gaymon Bennett The Ethics of Nanotechnology, Geoengineering, and Clean Energy Edited by Andrew Maynard and Jack Stilgoe The Ethics of Sports Technologies and Human Enhancement Edited by Thomas H. Murray and Voo Teck Chuan Emerging Technologies Edited by Gary E. Marchant and Wendell Wallach The Ethics of Information Technologies Edited by Keith W. Miller and Mariarosaria Taddeo Machine Ethics and Robot Ethics Edited by Wendell Wallach and Peter Asaro The Ethics of Military Technology Edited by Braden Allenby Machine Ethics and Robot Ethics Wendell Wallach, Yale University, USA, and Peter asaro, New School for Public Engagement, USA THE LIBRAY OF ESSAYS ON THE ETHICS OF EMERGING TECHNOLOGIES First published 2017 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN and by Routledge 711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business Editorial material and selection © 2017 Wendell Wallach and Peter Asaro; individual owners retain copyright in their own material. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. Trademark notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe. -

Figures Bibliography Curriculum Vitae

Cover Page The handle https://hdl.handle.net/1887/3134626 holds various files of this Leiden University dissertation. Author: Siglé, J.A. Title: From monsters to mediators: The evolution of the theme of altruism in early robotic science fiction texts Issue Date: 2021-01-28 List of Figures Figure 1: “The Steam-Powered Robot of 1868.” The Saturday Evening Post, 10 Mar. 2016, www.saturdayeveningpost.com/2016/03/10/history/post-perspective/the-steam-powered- robot-of-1868.html. Figure 2: “Zadoc Dederick.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 4 Nov. 2016 Figure 3: Scientific American (1845-1908); Apr 15, 1893; Vol. LXVIII., No. 15.; American Periodicals pg. 233 Figure 4: “The Steam-Powered Robot of 1868.” The Saturday Evening Post, 10 Mar. 2016, www.saturdayeveningpost.com/2016/03/10/history/post-perspective/the-steam-powered- robot-of-1868.html. Figure 5: Ebenstein, Joanna. The Anatomical Venus: Wax, God, Death & the Ecstatic. Distributed Art Publishers, 2016. Figure 6: “R.U.R.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 16 Mar. 2018, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/R.U.R. Figure 7: “R.U.R.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 16 Mar. 2018, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/R.U.R. Figure 8: Catalan, Cristobal. “Metropolis at 90: You'll Never See a Movie Like This Again.” The American Conservative, 2 Nov. 2017, www.theamericanconservative.com/blog/author/cristobal-catalan/. 200 Works Cited Aamoth, Doug. “Interview: Eugene Goostman Passes the Turing Test.” Time, Time, 9 June 2014, time.com/2847900/eugene-goostman-turing-test/. Adams, Douglas. The Hitch Hiker's Guide to the Galaxy. Picador, 2002. Alkon, Paul K. Science Fiction Before 1900: Imagination Discovers Technology. -

Dobby the Robot: the Science Fiction in Harry Potter

Volume 38 Number 1 Article 10 October 2019 Dobby the Robot: the Science Fiction in Harry Potter Emily Strand Mt. Carmel College of Nursing and Mythgard Institute Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation Strand, Emily (2019) "Dobby the Robot: the Science Fiction in Harry Potter," Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: Vol. 38 : No. 1 , Article 10. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol38/iss1/10 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Mythopoeic Society at SWOSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature by an authorized editor of SWOSU Digital Commons. An ADA compliant document is available upon request. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To join the Mythopoeic Society go to: http://www.mythsoc.org/join.htm Mythcon 51: A VIRTUAL “HALFLING” MYTHCON July 31 - August 1, 2021 (Saturday and Sunday) http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-51.htm Mythcon 52: The Mythic, the Fantastic, and the Alien Albuquerque, New Mexico; July 29 - August 1, 2022 http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-52.htm Abstract Science fiction author Arthur C. Clarke has famously argued that “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.” This paper starts by exploring a few general ways in which science fiction influences Harry Potter, then focuses attention on one key element of science fiction which Potter quite clearly appropriates: the classic trope of the robot or created servant. -

Robots and Their Multi Dimensional Skills in Literature

Journal of Information and Computational Science ISSN: 1548-7741 ROBOTS AND THEIR MULTI DIMENSIONAL SKILLS IN LITERATURE Author1 and Author2 1 S. Akila Research Scholar Department of English Annamalai University Chidambaram 2 Dr. A. Glory Research Supervisor Assistant Professor of English Department of English Annamalai University Chidambaram ABSTRACT The field of ‘Robotics’ has its origin in science fiction. The fictional world introduced robots in literature through the cybernetic tales. The term ‘robotics’ has been originated in the field of Literature and the genre science fiction planted the possibilities of the usage of robots in common world. Simultaneously it created attentiveness about this technology. This cybernetic imagination cropped up from the epic period itself. In Greek and Tamil mythology, the Gods created metal creature to assist the human being. In Homer’s Iliad, the Greek God Hephaistos had created two golden maids which could speak, spin, weave and do other works. In Tamil mythology, the speaking statue in Vikaramathiyan’s throne is the example for metal made creation. There are thirty two Bronze lady statues in the throne which depicted thirty two moral stories to Boja Rajan, the ruler. The purpose of creating artificial being is to facilitate the humanity. So from the mythological period, there has been need for artificial creatures that were said to be created by supernatural beings. Keywords: Robotics, Laws of Robotics, Positronic Brain, and Technophobia Science fiction has no doubt contributed to the development of robotics, by planting ideas in the minds of young people who might embark on career in robotics, and by creating awareness among the public about this technology.