Robotic Art and Cultural Imagination

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AI, Robots, and Swarms: Issues, Questions, and Recommended Studies

AI, Robots, and Swarms Issues, Questions, and Recommended Studies Andrew Ilachinski January 2017 Approved for Public Release; Distribution Unlimited. This document contains the best opinion of CNA at the time of issue. It does not necessarily represent the opinion of the sponsor. Distribution Approved for Public Release; Distribution Unlimited. Specific authority: N00014-11-D-0323. Copies of this document can be obtained through the Defense Technical Information Center at www.dtic.mil or contact CNA Document Control and Distribution Section at 703-824-2123. Photography Credits: http://www.darpa.mil/DDM_Gallery/Small_Gremlins_Web.jpg; http://4810-presscdn-0-38.pagely.netdna-cdn.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/ Robotics.jpg; http://i.kinja-img.com/gawker-edia/image/upload/18kxb5jw3e01ujpg.jpg Approved by: January 2017 Dr. David A. Broyles Special Activities and Innovation Operations Evaluation Group Copyright © 2017 CNA Abstract The military is on the cusp of a major technological revolution, in which warfare is conducted by unmanned and increasingly autonomous weapon systems. However, unlike the last “sea change,” during the Cold War, when advanced technologies were developed primarily by the Department of Defense (DoD), the key technology enablers today are being developed mostly in the commercial world. This study looks at the state-of-the-art of AI, machine-learning, and robot technologies, and their potential future military implications for autonomous (and semi-autonomous) weapon systems. While no one can predict how AI will evolve or predict its impact on the development of military autonomous systems, it is possible to anticipate many of the conceptual, technical, and operational challenges that DoD will face as it increasingly turns to AI-based technologies. -

Review of Advanced Medical Telerobots

applied sciences Review Review of Advanced Medical Telerobots Sarmad Mehrdad 1,†, Fei Liu 2,† , Minh Tu Pham 3 , Arnaud Lelevé 3,* and S. Farokh Atashzar 1,4,5 1 Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, New York University (NYU), Brooklyn, NY 11201, USA; [email protected] (S.M.); [email protected] (S.F.A.) 2 Advanced Robotics and Controls Lab, University of San Diego, San Diego, CA 92110, USA; [email protected] 3 Ampère, INSA Lyon, CNRS (UMR5005), F69621 Villeurbanne, France; [email protected] 4 Department of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering, New York University (NYU), Brooklyn, NY 11201, USA 5 NYU WIRELESS, Brooklyn, NY 11201, USA * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +33-0472-436035 † Mehrdad and Liu contributed equally to this work and share the first authorship. Abstract: The advent of telerobotic systems has revolutionized various aspects of the industry and human life. This technology is designed to augment human sensorimotor capabilities to extend them beyond natural competence. Classic examples are space and underwater applications when distance and access are the two major physical barriers to be combated with this technology. In modern examples, telerobotic systems have been used in several clinical applications, including teleoperated surgery and telerehabilitation. In this regard, there has been a significant amount of research and development due to the major benefits in terms of medical outcomes. Recently telerobotic systems are combined with advanced artificial intelligence modules to better share the agency with the operator and open new doors of medical automation. In this review paper, we have provided a comprehensive analysis of the literature considering various topologies of telerobotic systems in the medical domain while shedding light on different levels of autonomy for this technology, starting from direct control, going up to command-tracking autonomous telerobots. -

February8-2016-Ihmcbodminutes

IHMC Board of Directors Meeting Minutes Monday February 8, 2016 8:30 a.m. CST/9:30 a.m. EST Teleconference Meeting Roll Call Chair Ron Ewers Chair’s Greetings Chair Ron Ewers Action Items 1. Approval of December 7, 2015 Minutes Chair Ron Ewers 2. Approval of IHMC Conflict of Interest Policy Chair Ron Ewers Chief Executive Officer’s Report 1. Update on Pensacola Expansion Dr. Ken Ford 2. Research Update Dr. Ken Ford 3. Federal Legislative Update Dr. Ken Ford 4. State Legislative Update Dr. Ken Ford Other Items Adjournment IHMC Chair Ron Ewers called the meeting to order at 8:30 a.m. CST. Directors in attendance included: Dick Baker, Carol Carlan, Bill Dalton, Ron Ewers, Eugene Franklin, Hal Hudson, Jon Mills, Mort O’Sullivan, Alain Rappaport, Martha Saunders, Gordon Sprague and Glenn Sturm. Also in attendance were Ken Ford, Bonnie Dorr, Pam Dana, Sharon Heise, Row Rogacki, Phil Turner, Ann Spang, and Julie Sheppard. Chair Ewers welcomed and thanked everyone who dialed in this morning. He informed the Board that the next meeting is an in person meeting scheduled for Pensacola on Sunday, June 5 and Monday, June 6, 2016 adding that we would begin the event late Sunday afternoon with a dinner at the Union Public House and have a half day Board meeting in Pensacola on Monday the 6th. He asked all Board members to place this meeting date on their calendar as soon as possible and let Julie know if you are able to attend so we can solidify arrangements and book hotel rooms for out of town guests. -

2017 File Sesi

f e s t i v a l international l a n g u a g e festival internacionalelectronic de linguagem eletrônica o borbulhar de universos b u b b l i n g u n i v e r s e s Realização | Accomplishment FILE SÃO PAULO 2017 festival internacional de linguagem eletrônica file.org.br FILE FILE SÃO PAULO 2017 electronic l a n g u a g e international f e s t i v a l f e s t i v a l international l a n g u a g e festival internacionalelectronic de linguagem eletrônica o borbulhar de universos b u b b l i n g u n i v e r s e s Realização | Accomplishment FILE SÃO PAULO 2017 festival internacional de linguagem eletrônica file.org.br FILE FILE SÃO PAULO 2017 electronic l a n g u a g e international f e s t i v a l o borbulhar de universos b u b b l i n g u n i v e r s e s FILE SÃO PAULO 2017 festival internacional de linguagem eletrônica electronic l a n g u a g e international f e s t i v a l Dados Internacionais de Catalogação na Publicação (CIP) (Câmara Brasileira do Livro, SP, Brasil) o borbulhar de universos FILE São Paulo 2017 : Festival Internacional de Linguagem Eletrônica : o borbulhar de universos = FILE São Paulo b u b b l i n g u n i v e r s e s 2017 : Electronic Language International Festival : bubbling universes / organizadores Paula Perissinotto e Ricardo Barreto. -

Multisensory Real-Time Space Telerobotics

MULTISENSORY REAL-TIME SPACE TELEROBOTICS. DEVELOPMENT AND ANALYSIS OF REAL-TIME TELEROBOTICS SYSTEMS FOR SPACE EXPLORATION 1 3 Marta Ferraz , Edmundo Ferreira2, Thomas Krueger 1European Space Agency, Human-Robot Interaction Lab, Netherlands, E-mail: [email protected] 2European Space Agency, Human-Robot Interaction Lab, Netherlands, E-mail: [email protected] 3European Space Agency, Human-Robot Interaction Lab, Netherlands, E-mail: [email protected] space environments. The rationale in support of this ABSTRACT later argument is the difficulties in achieving human We introduce a research project whose goal is the exploration - due to current technical limitations on development and analysis of real-time telerobotic spacecraft and EVA technology (i.e., spacesuits) [31]. control setups for space exploration in stationary orbit Another key goal of space telerobotics has been and from deep-space habitats. We suggest a new preparing direct human space exploration - approach to real-time space telerobotics - Multisensory terraforming planetary bodies in order to support Real-time Space Telerobotics - in order to improve human expedition and, ultimately, Earth-like life [34]. perceptual functions in operators and surpass sensorimotor perturbations caused by altered gravity Lately, there has been a strong investment on the conditions. We submit that telerobotic operations, in preparation of Crew Surface Telerobotics (CST) such conditions, can be improved by offering enhanced missions for space exploration - the crew remotely sources of sensory information to the operator: operates surface robots from a spacecraft or deep-space combined visual, auditory, chemical and habitats [10]. These missions include Moon, Mars and somatosensory stimuli. We will characterize and Near-Earth Asteroid exploration [4, 16, 34]. -

The Meteron Supvis-Justin Telerobotic Experiment and the Solex Proving Ground

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: http://www.researchgate.net/publication/277268674 SIMULATING AN EXTRATERRESTRIAL ENVIRONMENT FOR ROBOTIC SPACE EXPLORATION: THE METERON SUPVIS-JUSTIN TELEROBOTIC EXPERIMENT AND THE SOLEX PROVING GROUND CONFERENCE PAPER · MAY 2015 READS 16 8 AUTHORS, INCLUDING: Neal Y. Lii Daniel Leidner German Aerospace Center (DLR) German Aerospace Center (DLR) 20 PUBLICATIONS 43 CITATIONS 10 PUBLICATIONS 28 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Benedikt Pleintinger German Aerospace Center (DLR) 9 PUBLICATIONS 11 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Available from: Neal Y. Lii Retrieved on: 24 September 2015 SIMULATING AN EXTRATERRESTRIAL ENVIRONMENT FOR ROBOTIC SPACE EXPLORATION: THE METERON SUPVIS-JUSTIN TELEROBOTIC EXPERIMENT AND THE SOLEX PROVING GROUND Neal Y. Lii1, Daniel Leidner1, Andre´ Schiele2, Peter Birkenkampf1, Ralph Bayer1, Benedikt Pleintinger1, Andreas Meissner1, and Andreas Balzer1 1Institute of Robotics and Mechatronics, German Aerospace Center (DLR), 82234 Wessling, Germany, Email: [email protected], [email protected] 2Telerobotics and Haptics Laboratory, ESA, 2201 AZ Noordwijk, The Netherlands, Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT This paper presents the on-going development for the Supvis-Justin experiment lead by DLR, together with ESA, planned for 2016. It is part of the ESA initiated Me- teron telerobotics experiment suite aimed to study differ- ent forms of telerobotics solutions for space applications. Supvis-Justin studies the user interface design, and super- vised autonomy aspects of telerobotics, as well as tele- operated tasks for a humanoid robot by teleoperating a dexterous robot on earth (located at DLR) from the Inter- national Space Station (ISS) with the use of a tablet PC. Figure 1. -

Humanoid Robots (Figures 41, 42)

A Roboethics Framework for the Development and Introduction of Social Assistive Robots in Elderly Care Antonio M. M. C. Espingardeiro Salford Business School University of Salford, Manchester, UK Submitted in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy, September 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter 1 - Introduction ......................................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter 2 - Literature review ................................................................................................................................. 9 2.1. Ethics in the digital world ................................................................................................................................ 9 2.2. Exploratory work in roboethics ..................................................................................................................... 14 2.2. Roboethics rules and guidance ...................................................................................................................... 18 2.3. “In-situ” practical workshops with SARs ........................................................................................................ 23 2.4. Summary ........................................................................................................................................................ 24 Chapter 3 - Human robotics interactions and ethical principles ......................................................................... -

The Roar Vol. 1, Edition 02 Rgb Final

Vol . 1 -2 1 | The Roar Monday, October 19, 2015 the ROAR LCHS NEWS LIVING IN THE SHADOW OF A SIBLING ! JACQUELINE RYAN Your older sibling does not define you. They set their W HAT’ S INSIDE… Junior High Writer own bar, but you should know that you do not have to ! compete with them. Do not put them on a pedestal, because no one is perfect. As Romans 3:23 says, “All L IVING IN THE SHADOW OF A SIBLING You may be wondering: “What does it Jacqueline Ryan mean to live in the shadow of an older have sinned and fallen short of the glory of God.” sibling?” It means that because your ! STUDENT SPOTLIGHT: JONAH sibling is successful, you feel as though Find your own strengths and do something new! You H INTON’ S PAPER you must also be successful in order to don’t have to join the same clubs as your siblings, nor Sydney Beech feel a sense of accomplishment and self- do you have to play the same sports. Learn from their worth. mistakes, as well as the good things they did. You are J OKES FROM DR . SHUMAN ! your own person. God created you. You are unique. Tom Scoggin Quite a few junior high students at LCHS are younger ! While I was talking to Grace Jones, she said she feels T HE TWO DOLLAR DILEMMA siblings to upperclassmen. On the first day of school, a Tom Scoggin few of you probably heard a teacher say, “I know your like she has to live up to her older sisters because they brother/sister” as they were reading roll call. -

A Study of Potential Applications of Automation and Robotics Technology in Construction, Maintenance and Operation of Highway Systems: a Final Report

A Study of Potential Applications of Automation and Robotics Technology in Construction, Maintenance and Operation of Highway Systems: A Final Report Ernest Kent Intelligent Systems Division U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE Technology Administration National Institute of Standards and Technology Bldg. 220 Rm. B124 Gaithersburg, MD 20899 QC 100 .U56 NIST NO. 5667 1995 V.1 A Study of Potential Applications of Automation and Robotics Technology in Construction, Maintenance and Operation of Highway Systems: A Final Report Ernest Kent Intelligent Systems Division U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE Technoiogy Administration Nationai Institute of Standards and Technology Bldg. 220 Rm. B124 Gaithersburg, MD 20899 June 1995 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE Ronaid H. Brown, Secretary TECHNOLOGY ADMiNISTRATION Mary L. Good, Under Secretary for Techrwlogy NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF STANDARDS AND TECHNOLOGY Arati Prabhakar, Director FINAL REPORT VOLUME: 1 To: FEDERAL HIGHWAY ADMINISTRATION Prepared by: NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF STANDARDS AND TECHNOLOGY Dr. Ernest Kent ' Vi \1 ;i ;4i V’jI’4 vP '’'. ^'^' .^. '-i'^- :'ii: ji I^.v • </ V; y :j 1,-'^ TABLE OF CONTENTS Volume: 1 ***This Volume*** Section Acknowledgments 1 Executive Summary 2 Overview of the Study 3 Summary of Results and Recommendations 4 White Papers on Selected Topics 5 Bibliographic Study 6 Volume: 2 Technology Proposals Submitted for Evaluation 7 CERF Cost/Benefits Analysis of Technology Proposals Measures of Merit 8 Volume: 3 1st Workshop Report: Industry Views and Requirements 9 2nd Workshop Report: Technical State of the Art 1 0 Volume: 4 Final Proposals for Potential Research Efforts 11 Abstract. The National Institute of Standards and Technology, at the request of the Federal Highway Administration, has conducted a study of potential appli- cations of automation and robotics technology in construction, maintenance, and operation of highway systems. -

The Ranger Telerobotic Shuttle Experiment: an On-Orbit Satellite Servicer

THE RANGER TELEROBOTIC SHUTTLE EXPERIMENT: AN ON-ORBIT SATELLITE SERVICER Joseph C. Parrish NASA Headquarters Office of Space Science, Advanced Technologies & Mission Studies Division Mail Code SM, Washington, DC, 20546-0001, U.S.A. phone: +1 301 405 0291, fax: +1 209 391 9785, e-mail: [email protected] Abstract 1 Introduction As space operations enter the 21st century, the role The Ranger Telerobotic Shuttle Experiment (RTSX) of robotic satellite servicing systems will increase dra- is a Space Shuttle-based flight experiment to demon- matically. Several such systems are currently in de- strate key telerobotic technologies for servicing as- velopment for use on the International Space Sta- sets in Earth orbit. The flight system will be tele- tion, including the Canadian Mobile Servicing Sys- operated from onboard the Space Shuttle and from a tem (MSS)[2] and the Japanese Experiment Module ground control station at the NASA Johnson Space Remote Manipulator System (JEM-RMS). Another Center. The robot, along with supporting equipment Japanese system, the Experimental Test System VII and task elements, will be located in the Shuttle pay- (ETS-VII) [I],has already demonstrated the ability for load bay. A number of relevant servicing operations rendezvous and docking, followed by ORU manipula- will be performed-including extravehicular activity tion under supervisory control. Under development by (EVA) worksite setup, orbit replaceable unit (ORU) the United States, the Ranger Telerobotic Shuttle Ex- exchange, and other dexterous tasks. The program periment (RTSX)[3] is progressing toward its mission is underway toward an anticipated launch date in on the NASA Space Shuttle to demonstrate telerobotic CY2001, and the hardware and software for the flight servicing of orbital assets. -

Telepresence Enclosure: VR, Remote Work, and the Privatization of Presence in a Shrinking Japan

Telepresence Enclosure: VR, Remote Work, and the Privatization of Presence in a Shrinking Japan The MIT Faculty has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters. Citation Roquet, Paul. "Telepresence Enclosure: VR, Remote Work, and the Privatization of Presence in a Shrinking Japan." Media Theory 4, 1 (November 2020): 33-62. As Published https://journalcontent.mediatheoryjournal.org/index.php/mt/article/ view/109 Publisher Pubilc Knowledge Project Version Final published version Citable link https://hdl.handle.net/1721.1/130241 Terms of Use Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs License Detailed Terms http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Article Telepresence Enclosure: Media Theory Vol. 4 | No. 1 | 33-62 © The Author(s) 2020 VR, Remote Work, and the CC-BY-NC-ND http://mediatheoryjournal.org/ Privatization of Presence in a Shrinking Japan PAUL ROQUET Massachusetts Institute of Technology, USA Abstract Virtual reality proponents often promise the technology will allow a more fully embodied sense of presence at a distance, or what researchers have called ‗telepresence.‘ Departing from telepresence‘s original focus on providing access to dangerous environments, VR and robotics researchers in Japan now promote everyday service and factory work via telerobots as a solution to the country‘s rapidly shrinking workforce. Telepresence becomes a way to access the physical labor of the elderly, persons with disabilities, and foreign workers, while at the same time keeping them fixed in place at home or behind closed borders. This essay theorizes the perceptual segregation imposed by these immersive labor platforms as a form of telepresence enclosure: the mediated privatization of presence itself. -

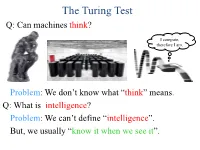

The Turing Test Q: Can Machines Think?

The Turing Test Q: Can machines think? I compute, therefore I am. Problem: We don’t know what ―think‖ means. Q: What is intelligence? Problem: We can’t define ―intelligence‖. But, we usually ―know it when we see it‖. The Turing Test Q: Which of the following can think? The Turing Test Q: Can you distinguish a machine from a person? ≡ Can a machine impersonate a person? The Turing Test • The first deep investigation into whether machines can ―behave intelligently‖ • Helped usher in field of AI • Decoupled ―intelligence‖ from ―human‖ • Based ―intelligence‖ on I/O, not entity’s ―look and feel‖ • Proposed a practical, formal test for intelligence • Definitions & test are operational & easily implementable • Turing test variants: ―immortality‖, ―fly-on-wall‖, ―meta‖, ―reverse‖, ―subject matter expert‖, ―compression‖, ―minimum intelligent signal‖ Turing Test Milestones Turk (von Kempelen), 1770: • Played a strong game of chess • Toured the world for 84 years • Generated much interest in automata • Was a hoax (hidden human operator) Turing Test Milestones Eliza (Weizenbaum), 1966: • First ―chatterbot‖ • Named after ―Eliza Doolittle‖ of Shaw’s Pygmalion • Simulated Rogerian psychotherapist • Often convinced people it is human • Influence computer games (e.g., Dungeon, Adventure) • Inspired Arthur C. Clarke’s HAL 9000 • Chatterbots appear today in chatrooms and dating services • Chatterbot competitions (Turing Test format): – Loebner Prize – Chatterbox Challenge, 2010 Turing Test Milestones Elbot, 2008: • Won 2008 Loebner Prize • Fooled 3 of 12 judges (Turing: >30%) • Typical excerpt: Judge: What's your favourite novel? Elbot: I often read telephone books, or dadaist poetry: Brä brä brä Judge: Typical computer! Elbot: You tend towards generalizations.