Chlorpyrifos

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Global Insecticide Use for Vector-Borne Disease Control

WHO/CDS/NTD/WHOPES/GCDPP/2007.2 GLOBAL INSECTICIDE USE FOR VECTOR-BORNE DISEASE CONTROL M. Zaim & P. Jambulingam DEPARTMENT OF CONTROL OF NEGLECTED TROPICAL DISEASES (NTD) WHO PESTICIDE EVALUATION SCHEME (WHOPES) First edition, 2002 Second edition, 2004 Third edition, 2007 © World Health Organization 2007 All rights reserved. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted lines on maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement. The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by the World Health Organization in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. Errors and omissions excepted, the names of proprietary products are distinguished by initial capital letters. All reasonable precautions have been taken by the World Health Organization to verify the information contained in this publication. However, the published material is being distributed without warranty of any kind, either express or implied. The responsibility for the interpretation and use of the material lies with the reader. In no event shall the World Health Organization be liable for damages arising from its use. The named authors alone are responsible for the views expressed in this publication. CONTENTS Page Acknowledgements i Introduction 1 Collection of information 2 Data analysis and observations on reporting 3 All uses in vector control 6 Malaria vector control 22 Dengue vector control 38 Chagas disease vector control 48 Leishmaniasis vector control 52 Other vector-borne disease control 56 Selected insecticides – DDT 58 Selected insecticides – Insect growth regulators 60 Selected insecticides – Bacterial larvicides 62 Country examples 64 Annex 1. -

What Is the Difference Between Pesticides, Insecticides and Herbicides? Pesticide Effects on Food Production

What is the Difference Between Pesticides, Insecticides and Herbicides? Pesticides are chemicals that may be used to kill fungus, bacteria, insects, plant diseases, snails, slugs, or weeds among others. These chemicals can work by ingestion or by touch and death may occur immediately or over a long period of time. Insecticides are a type of pesticide that is used to specifically target and kill insects. Some insecticides include snail bait, ant killer, and wasp killer. Herbicides are used to kill undesirable plants or “weeds”. Some herbicides will kill all the plants they touch, while others are designed to target one species. Pesticide Effects on Food Production As the human population continues to grow, more and more crops are needed to meet this growing demand. This has increased the use of pesticides to increase crop yield per acre. For example, many farmers will plant a field with Soybeans and apply two doses of Roundup throughout the growing year to remove all other plants and prepare the field for next year’s crop. The Roundup is applied twice through the growing season to kill everything except the soybeans, which are modified to be pesticide resistant. After the soybeans are harvested, there is little vegetative cover on the field creating potential erosion issues for the reason that another crop can easily be planted. With this method, hundreds of gallons of chemicals are introduced into the environment every year. All these chemicals affect wildlife, insects, water quality and air quality. One greatly affected “good” insect are bees. Bees play a significant role in the pollination of the foods that we eat. -

Novel Approach to Fast Determination of 64 Pesticides Using of Ultra-Performance Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry

Novel approach to fast determination of 64 pesticides using of ultra-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (UPLC-MS/MS) Tomas Kovalczuk, Ondrej Lacina, Martin Jech, Jan Poustka, Jana Hajslova To cite this version: Tomas Kovalczuk, Ondrej Lacina, Martin Jech, Jan Poustka, Jana Hajslova. Novel approach to fast determination of 64 pesticides using of ultra-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (UPLC-MS/MS). Food Additives and Contaminants, 2008, 25 (04), pp.444-457. 10.1080/02652030701570156. hal-00577414 HAL Id: hal-00577414 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00577414 Submitted on 17 Mar 2011 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Food Additives and Contaminants For Peer Review Only Novel approach to fast determination of 64 pesticides using of ultra-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (UPLC-MS/MS) Journal: Food Additives and Contaminants Manuscript ID: TFAC-2007-065.R1 Manuscript Type: Original Research Paper Date Submitted by the 07-Jul-2007 Author: Complete List of Authors: -

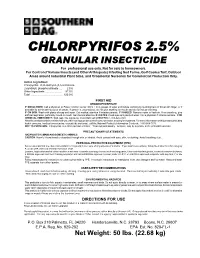

CHLORPYRIFOS 2.5% GRANULAR INSECTICIDE for Professional Use Only

CHLORPYRIFOS 2.5% GRANULAR INSECTICIDE For professional use only. Not for sale to homeowners. For Control of Various Insects (and Other Arthropods) Infesting Sod Farms, Golf Course Turf, Outdoor Areas around Industrial Plant Sites, and Ornamental Nurseries for Commercial Production Only. Active Ingredient: Chlorpyrifos: O,O-diethyl-0-(3,5,6-trichloro- 2-pyridinyl) phosphorothioate .... 2.5% Other Ingredients ....................... 97.5% Total ............................................ 100.0% FIRST AID ORGANOPHOSPHATE IF SWALLOWED: Call a physician or Poison Control Center. Drink 1 or 2 glasses of water and induce vomiting by touching back of throat with finger, or if available by administering syrup of ipecac. If person is unconscious, do not give anything by mouth and do not induce vomiting. IF ON SKIN: Wash with plenty of soap and water. Get medical attention if irritation persists. IF INHALED: Remove victim to fresh air. If not breathing, give artificial respiration, preferably mouth-to-mouth. Get medical attention. IF IN EYES: Flush eyes with plenty of water. Call a physician if irritation persists. FOR CHEMICAL EMERGENCY: Spill, leak, fire, exposure, or accident call CHEMTREC 1-800-424-9300. Have the product container or label with you when calling a poison control center or doctor, or going for treatment. For more information on this product (including health concerns, medical emergencies, or pesticide incidents), call the National Pesticide Information Center at: 1-800-858-7378. NOT TO PHYSICIAN: Chlorpyrifos is a cholinesterase inhibitor. Treat symptomatically. Atropine, only by injection, is the preferable antidote. PRECAUTIONARY STATEMENTS HAZARDS TO HUMANS AND DOMESTIC ANIMALS CAUTION: Harmful if swallowed or absorbed through skin or inhaled. -

Development of a CEN Standardised Method for Liquid Chromatography Coupled to Accurate Mass Spectrometry

Development of a CEN standardised method for liquid chromatography coupled to accurate mass spectrometry CONTENTS 1. Aim and scope ................................................................................................................. 2 2. Short description ................................................................................................................ 2 3. Apparatus and consumables ......................................................................................... 2 4. Chemicals ........................................................................................................................... 2 5. Procedure ........................................................................................................................... 3 5.1. Sample preparation ................................................................................................... 3 5.2. Recovery experiments for method validation ...................................................... 3 5.3. Extraction method ...................................................................................................... 3 5.4. Measurement .............................................................................................................. 3 5.5. Instrumentation and analytical conditions ............................................................ 4 5.5.1. Dionex Ultimate 3000 .......................................................................................... 4 5.5.2. QExactive Focus HESI source parameters ..................................................... -

Historical Use of Lead Arsenate and Survey of Soil Residues in Former Apple Orchards in Virginia

HISTORICAL USE OF LEAD ARSENATE AND SURVEY OF SOIL RESIDUES IN FORMER APPLE ORCHARDS IN VIRGINIA by Therese Nowak Schooley Thesis submitted to the faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE IN LIFE SCIENCES in Entomology Michael J. Weaver, Chair Donald E. Mullins, Co-Chair Matthew J. Eick May 4, 2006 Blacksburg, Virginia Keywords: arsenic, lead, lead arsenate, orchards, soil residues, historical pesticides HISTORICAL USE OF LEAD ARSENATE AND SURVEY OF SOIL RESIDUES IN FORMER APPLE ORCHARDS IN VIRGINIA Therese Nowak Schooley Abstract Inorganic pesticides including natural chemicals such as arsenic, copper, lead, and sulfur have been used extensively to control pests in agriculture. Lead arsenate (PbHAsO4) was first used in apple orchards in the late 1890’s to combat the codling moth, Cydia pomonella (Linnaeus). The affordable and persistent pesticide was applied in ever increasing amounts for the next half century. The persistence in the environment in addition to the heavy applications during the early 1900’s may have led to many of the current and former orchards in this country being contaminated. In this study, soil samples were taken from several apple orchards across the state, ranging from Southwest to Northern Virginia and were analyzed for arsenic and lead. Based on naturally occurring background levels and standards set by other states, two orchards sampled in this study were found to have very high levels of arsenic and lead in the soil, Snead Farm and Mint Spring Recreational Park. Average arsenic levels at Mint Spring Recreational Park and Snead Farm were found to be 65.2 ppm and 107.6 ppm, respectively. -

Guidance for POP Pesticides

Guidance for POP pesticides 1. Background on POP pesticides POPs Pesticides originate almost entirely from anthropogenic sources and are associated largely with the manufacture, use and disposition of certain organic chemicals. Of the initial 12 POPs chemicals, eight are POPs pesticide. In the new POP list, five chemicals may be categorised as pesticides. These are alpha hexachlorocyclohexane (alpha-HCH), beta hexachlorocyclohexane (beta-HCH), Chlordecone, Lindane (gamma, 1,2,3,4,5,6- hexaclorocyclohexane) and Pentachlorobenzene. This module addresses baseline data gathering and assessment of POPs pesticides. Particular care is required to address DDT due to its use for vector control and Lindane due to its use for control of ecto-parasites in veterinary and human application, which may be under the responsibility of authorities other than those responsible for primarily agricultural chemicals. In addition, it is important that all uses of HCB, alpha hexachorocyclohexane, beta hexachlorocyclohexane and pentachlorobenzene (industrial as well as pesticide) be properly addressed. Specialists with knowledge of each of these areas might be included in the task teams. 2. Objective To review and summarize the production, use, import and export of the chemicals listed in Annex A and Annex B of the Convention (excluding other chemicals listed under Annex A and B which are not considered as pesticides). To gather information on stockpiles and wastes containing, or thought to contain, POPs pesticides. To assess the legal and institutional framework for control of the production, use, import, export and disposal of the chemicals listed in Annex A and Annex B (excluding other chemicals which are not classed as pesticides) of the Convention. -

162998571.Pdf

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Liverpool Repository Please do not adjust margins Investigating the breakdown of the nerve agent simulant methyl paraoxon and chemical warfare agents GB and VX using nitrogen containing bases Received 00th January 20xx, Accepted 00th January 20xx Craig Wilson,a Nicholas J. Cooper,b Michael E. Briggs,a Andrew I. Cooper,*a and Dave J. Adams*c DOI: 10.1039/x0xx00000x A range of nitrogen containing bases was tested for the hydrolysis of a nerve agent simulant, methyl paraoxon (MP), and www.rsc.org/ the chemical warfare agents, GB and VX. The product distribution was found to be highly dependant on the basicity of the base and the quantity of water used for the hydrolysis. This study is important in the design of decontamination technology, which often involve mimics of CWAs. production of EA-2192 Introduction (S-(2-diisopropylaminoethyl) methylphosphonothioic acid), which exhibits roughly the same toxicity as VX itself.12 The Chemical warfare agents (CWAs) have a devastating effect on blister agent HD (Fig. 1d) can also undergo deactivation via the body and will disable or kill on exposure. Blister agents, such hydrolysis.13 However, its poor water solubility reduces the as sulfur mustard (HD, bis(2-chloroethyl) sulfide), target the skin efficiency of this decontamination method.14 As a result, and respiratory system causing severe pain and damage to the oxidation to the sulfoxide, or the addition of a co-solvent is most body whereas nerve agents, such as sarin (GB, isopropyl commonly used for HD deactivation.15-17 methylphosphonofluoridate) and VX (O-ethyl The high toxicity of CWAs means that research into their S-[2-(diisopropylamino)ethyl] methylphosphonothioate), target deactivation is often carried out using simulants. -

Past Use of Chlordane, Dieldrin, And

The Hazard Evaluation and Emergency Response Office (HEER Office) is part of the Hawai‘i Department of Health (HDOH) Environmental Health Administration, whose mission is to protect human health and the environment. The HEER Office provides leadership, support, and partnership in preventing, planning for, responding to, and enforcing environmental laws relating to releases or threats of releases of hazardous substances. Past Use of Chlordane, Dieldrin, and other Organochlorine Pesticides for Termite Control in Hawai‘i: Safe Management Practices around Treated Foundations or during Building Demolition This fact sheet provides building owners, demolition and construction contractors, developers, realtors, and others with an overview of the potential environmental concerns associated with the past use of organochlorine termiticides (pesticides used to control termites) in Hawai‘i. In addition, this fact sheet discusses methods for reducing exposure to organochlorine termiticides during building demolition or around the foundations of treated buildings and identifies resources for further information. What are organochlorine termiticides? Organochlorine termiticides are a group of pesticides that were used for termite control in and around wooden buildings and homes from the mid-1940s to the late 1980s. These organochlorine pesticides included chlordane, aldrin, dieldrin, heptachlor, and dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT). They were used primarily by pest control operators in Hawaii’s urban areas, but also by homeowners, the military, the state, and counties to protect buildings against termite damage. In the 1970s and 1980s, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) banned all uses of these organochlorine pesticides except for heptachlor, which can be used today only for control of fire ants in underground power transformers. -

Chlorpyrifos (Dursban) Ddvp (Dichlorvos) Diazinon Malathion Parathion

CHLORPYRIFOS (DURSBAN) DDVP (DICHLORVOS) DIAZINON MALATHION PARATHION Method no.: 62 Matrix: Air Procedure: Samples are collected by drawing known volumes of air through specially constructed glass sampling tubes, each containing a glass fiber filter and two sections of XAD-2 adsorbent. Samples are desorbed with toluene and analyzed by GC using a flame photometric detector (FPD). Recommended air volume and sampling rate: 480 L at 1.0 L/min except for Malathion 60 L at 1.0 L/min for Malathion Target concentrations: 1.0 mg/m3 (0.111 ppm) for Dichlorvos (PEL) 0.1 mg/m3 (0.008 ppm) for Diazinon (TLV) 0.2 mg/m3 (0.014 ppm) for Chlorpyrifos (TLV) 15.0 mg/m3 (1.11 ppm) for Malathion (PEL) 0.1 mg/m3 (0.008 ppm) for Parathion (PEL) Reliable quantitation limits: 0.0019 mg/m3 (0.21 ppb) for Dichlorvos (based on the RAV) 0.0030 mg/m3 (0.24 ppb) for Diazinon 0.0033 mg/m3 (0.23 ppb) for Chlorpyrifos 0.0303 mg/m3 (2.2 ppb) for Malathion 0.0031 mg/m3 (0.26 ppb) for Parathion Standard errors of estimate at the target concentration: 5.3% for Dichlorvos (Section 4.6.) 5.3% for Diazinon 5.3% for Chlorpyrifos 5.6% for Malathion 5.3% for Parathion Status of method: Evaluated method. This method has been subjected to the established evaluation procedures of the Organic Methods Evaluation Branch. Date: October 1986 Chemist: Donald Burright Organic Methods Evaluation Branch OSHA Analytical Laboratory Salt Lake City, Utah 1 of 27 T-62-FV-01-8610-M 1. -

EPA Listed Wastes Table 1: Maximum Concentration of Contaminants For

EPA Listed Wastes Table 1: Maximum concentration of contaminants for the toxicity characteristic, as determined by the TCLP (D list) Regulatory HW No. Contaminant CAS No. Level (mg/L) D004 Arsenic 7440-38-2 5.0 D005 Barium 7440-39-3 100.0 D0018 Benzene 71-43-2 0.5 D006 Cadmium 7440-43-9 1.0 D019 Carbon tetrachloride 56-23-5 0.5 D020 Chlordane 57-74-9 0.03 D021 Chlorobenzene 108-90-7 100.0 D022 Chloroform 67-66-3 6.0 D007 Chromium 7440-47-3 5.0 D023 o-Cresol 95-48-7 200.0** D024 m-Cresol 108-39-4 200.0** D025 p-Cresol 106-44-5 200.0** D026 Cresol ------------ 200.0** D016 2,4-D 94-75-7 10.0 D027 1,4-Dichlorobenzene 106-46-7 7.5 D028 1,2-Dichloroethane 107-06-2 0.5 D029 1,1-Dichloroethylene 75-35-4 0.7 D030 2,4-Dinitrotoluene 121-14-2 0.13* D012 Endrin 72-20-8 0.02 D031 Heptachlor 76-44-8 0.008 D032 Hexachlorobenzene 118-74-1 0.13* D033 Hexachlorobutadiene 87-68-3 0.5 D034 Hexachloroethane 67-72-1 3.0 D008 Lead 7439-92-1 5.0 D013 Lindane 58-89-9 0.4 D009 Mercury 7439-97-6 0.2 D014 Methoxychlor 72-43-5 10.0 D035 Methyl ethyl ketone 78-93-3 200.0 D036 Nitrobenzene 98-95-3 2.0 D037 Pentachlorophenol 87-86-5 100.0 D038 Pyridine 110-86-1 5.0* D010 Selenium 7782-49-2 1.0 D011 Silver 7740-22-4 5.0 D039 Tetrachloroethylene 127-18-4 0.7 D015 Toxaphene 8001-35-2 0.5 D040 Trichloroethylene 79-01-6 0.5 D041 2,4,5-Trichlorophenol 95-95-4 400.0 D042 2,4,6-Trichlorophenol 88-06-2 2.0 D017 2,4,5-TP (Silvex) 93-72-1 1.0 D043 Vinyl Chloride 74-01-4 0.2 * Quantitation limit is greater than the calculated regulatory level. -

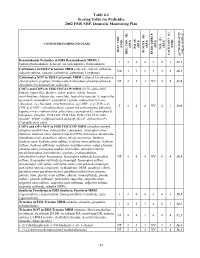

2002 NRP Section 6, Tables 6.1 Through

Table 6.1 Scoring Table for Pesticides 2002 FSIS NRP, Domestic Monitoring Plan } +1 0.05] COMPOUND/COMPOUND CLASS * ) (EPA) (EPA) (EPA) (EPA) (EPA) (FSIS) (FSIS) PSI (P) TOX.(T) L-1 HIST. VIOL. BIOCON. (B) {[( (2*R+P+B)/4]*T} REG. CON. (R) * ENDO. DISRUP. LACK INFO. (L) LACK INFO. {[ Benzimidazole Pesticides in FSIS Benzimidazole MRM (5- 131434312.1 hydroxythiabendazole, benomyl (as carbendazim), thiabendazole) Carbamates in FSIS Carbamate MRM (aldicarb, aldicarb sulfoxide, NA44234416.1 aldicarb sulfone, carbaryl, carbofuran, carbofuran 3-hydroxy) Carbamates NOT in FSIS Carbamate MRM (carbaryl 5,6-dihydroxy, chlorpropham, propham, thiobencarb, 4-chlorobenzylmethylsulfone,4- NT 4 1 3 NV 4 4 13.8 chlorobenzylmethylsulfone sulfoxide) CHC's and COP's in FSIS CHC/COP MRM (HCB, alpha-BHC, lindane, heptachlor, dieldrin, aldrin, endrin, ronnel, linuron, oxychlordane, chlorpyrifos, nonachlor, heptachlor epoxide A, heptachlor epoxide B, endosulfan I, endosulfan I sulfate, endosulfan II, trans- chlordane, cis-chlordane, chlorfenvinphos, p,p'-DDE, p, p'-TDE, o,p'- 3444NV4116.0 DDT, p,p'-DDT, carbophenothion, captan, tetrachlorvinphos [stirofos], kepone, mirex, methoxychlor, phosalone, coumaphos-O, coumaphos-S, toxaphene, famphur, PCB 1242, PCB 1248, PCB 1254, PCB 1260, dicofol*, PBBs*, polybrominated diphenyl ethers*, deltamethrin*) (*identification only) COP's and OP's NOT in FSIS CHC/COP MRM (azinphos-methyl, azinphos-methyl oxon, chlorpyrifos, coumaphos, coumaphos oxon, diazinon, diazinon oxon, diazinon met G-27550, dichlorvos, dimethoate, dimethoate