Joshua Nielson the Werewolf's Mate

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pros and Cons Celebrity Client List.Pages

Pros And Cons, www.prosandconsla.com, is a professional talent booking company specializing in connecting celebrity talent, from all walks of pop culture, to comic conventions and other fan events around the globe. Film, TV, Comics, Star Wars, Vampires, Fantasy, Crime and More! Pros And Cons has the talent you need to make your Pop Culture Event a FANtastic success! The following actors are currently available: T.J. Thyne starred in Fox TV’s Bones for 12 seasons, playing Dr. Jack Hodgins, the resident “bug guy” and conspiracy theorist. Along with his long running character on Bones, TJ is loved for playing Stu Lou Who in How The Grinch Stole Christmas starring Jim Carrey and Gerald in How High. In addition, TJ has a dedicated following around the world for the award winning inspirational short film, Validation, directed by Kurt Kuenne (Batkid Begins, Dear Zachary). TJ’s other notable TV appearances include Angel, Friends, 24, Walker, Texas Ranger, Huff and more! ! Michaela Conlin starred in Fox TV’s Bones for 12 seasons, playing forensic artist, Angela Montenegro. Prior to her work on Bones, she played Dr. Maggie Yang on the TV medical drama, MDs. She can be seen in the feature films Enchanted, Baby, Baby, Baby, The Disappointments Room and Open Window. Michaela’s other notable TV appearances include JAG, Law & Order, The Lincoln Lawyer, The D.A., The Division and more! ! Tamara Taylor starred in Fox TV’s Bones for 11 years, playing Dr. Camille Saroyan. She can now be seen on Netflix, starring as Oumou Prescott on the Sci-Fi series Altered Carbon. -

Jeudi 05 Août 2021

Jeudi 23 septembre 2021 7.00 Le double expresso son côté, McGee espère 18.50 Les Marseillais vs le Héloïse Martin, Rayane passer la nuit dans la maison Bensetti, Sylvie Testud, Cyril RTL2 d'un collègue : une tempête a, reste du monde Gueï, Lou Gala Divertissement en effet, provoqué des pannes Déconseillé aux moins de 10 de courant dans la ville.... Série 15.00 NCIS Saison 6 9.00 W9 Hits Cela fait 6 ans que la famille Série avec Mark Harmon, Clips des Marseillais et la famille du Michael Weatherly, Pauley Reste du Monde s'affrontent Perrette, Sean Murray, David sans relâche pour soulever la McCallum 10.30 W9 Hits Gold coupe ! À ce stade, 3 victoires Saison 13 pour les Marseillais contre Clips De profundis seulement 2 pour le Reste du Quand un scaphandrier est Monde. Mais cette année, assassiné sur son lieu de attention : la famille du Reste 11.35 W9 Hits travail, son corps, ainsi que du Monde, conduite par Nikola, Avec ses kilos en trop, Tamara se présente dans cette Clips ses collègues suspectés du n'est pas bien dans sa peau. meurtre, doivent rester dans compétition plus soudée que Pour faire taire ses camarades une chambre de jamais et super entrainée, prête qui se moquent d'elle, elle parie décompression pendant quatre à tout pour dominer le jeu ! avec sa meilleure amie qu'elle 12.45 Météo jours entiers. Les agents du Dans ce duel implacable, parviendra à sortir avec le Météo NCIS en profitent pour faire aucune des deux familles ne prochain garçon qui se avancer cette enquête peu sera épargnée : l'heure de présentera en classe. -

John Boyd and John Warden: Air Power's Quest for Strategic Paraylsis

John Boyd and John Warden Air Power’s Quest for Strategic Paralysis DAVID S. FADOK, Major, USAF School of Advanced Airpower Studies THESIS PRESENTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE SCHOOL OF ADVANCED AIRPOWER STUDIES, MAXWELL AIR FORCE BASE, ALABAMA, FOR COMPLETION OF GRADUATION REQUIREMENTS, ACADEMIC YEAR 1993–94 Air University Press Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama February 1995 Disclaimer This publication was produced in the Department of Defense school environment in the interest of academic freedom and the advancement of national defense-related concepts. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of Defense or the United States government. This publication has been reviewed by security and policy review authorities and is cleared for public release. ii Contents Chapter Page DISCLAIMER . ii ABSTRACT . v ABOUT THE AUTHOR . vii 1 INTRODUCTION . 1 Notes . 4 2 THE NOTION OF STRATEGIC PARALYSIS . 5 Notes . 10 3 BOYD’S THEORY OF STRATEGIC PARALYSIS . 13 Notes . 20 4 WARDEN’S THEORY OF STRATEGIC PARALYSIS . 23 Notes . 30 5 CLAUSEWITZ AND JOMINI REVISITED . 33 Notes . 37 6 BOYD, WARDEN, AND THE EVOLUTION OF AIR POWER THEORY . 39 The Past—Paralysis by Economic Warfare and Industrial Targeting . 39 The Present—Paralysis by Control Warfare and Command Targeting . 41 The Future—Paralysis by Control Warfare and Informational Targeting . 42 Notes . 44 7 CONCLUSION . 47 Notes . 50 BIBLIOGRAPHY . 51 Illustrations Figure 1 Boyd’s OODA Loop . 16 2 Boyd’s Theory of Conflict . 17 3 Warden’s Five Strategic Rings . 25 4 Warden’s Theory of Strategic Attack . -

Restoring Law and Order Black Patch War

Restoring Law and Order: The Kentucky State Guard in the Black Patch War of 1907-1909 A Monograph by MAJ Andrew J. Bates Kentucky Army National Guard School of Advanced Military Studies United States Army Command and General Staff College Fort Leavenworth, Kansas AY 2011 Approved for Public Release; Distribution is Unlimited Form Approved REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE OMB No. 074-0188 Public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instructions, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing this collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden to Washington Headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports, 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302, and to the Office of Management and Budget, Paperwork Reduction Project (0704-0188), Washington, DC 20503 1. AGENCY USE ONLY (Leave blank) 2. REPORT DATE 3. REPORT TYPE AND DATES COVERED March 21, 2011 Monograph, 1907-1909 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5. FUNDING NUMBERS Restoring Law and Order: The Kentucky State Guard in the Black Patch War of 1907-1909 6. AUTHOR(S) Major Andrew J. Bates 7. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 8. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION REPORT NUMBER School of Advanced Military Studies 250 Gibbon Avenue Fort Leavenworth, KS 66027-2134 9. SPONSORING / MONITORING AGENCY NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 10. SPONSORING / MONITORING Command and General Staff College AGENCY REPORT NUMBER 731 McClellan Avenue Fort Leavenworth, KS 66027-1350 11. -

Champagne and Meatballs: Adventures of a Canadian Communist by Bert Whyte, Edited and with an Introduction by Larry Hannant

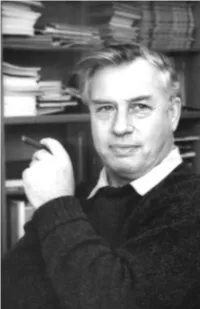

Champagne_and_Meatballs_Interior.indd 1 11/01/11 1:45 PM Whyte in his prime, cigar at the ready, in Moscow, about 1968 Champagne_and_Meatballs_Interior.indd 2 11/01/11 1:45 PM Champagne and Meatballs Champagne_and_Meatballs_Interior.indd 3 11/01/11 1:45 PM Working Canadians: Books from the CCLH Series editors: Alvin Finkel and Greg Kealey The Canadian Committee on Labour History is Canada’s or- ganization of historians and other scholars interested in the study of the lives and struggles of working people throughout Canada’s past. Since 1976, the CCLH has published Labour/Le travail, Canada’s pre-eminent scholarly journal of labour stud- ies. It also publishes books, now in conjunction with AU Press, that focus on the history of Canada’s working people and their organizations. The emphasis in this series is on materials that are accessible to labour audiences as well as university audi- ences rather than simply on scholarly studies in the labour area. This includes documentary collections, oral histories, auto biographies, bio graphies, and provincial and local labour movement histories with a popular bent. Series Titles Champagne and Meatballs: Adventures of a Canadian Communist by Bert Whyte, edited and with an introduction by Larry Hannant Champagne_and_Meatballs_Interior.indd 4 11/01/11 1:45 PM Champagne and MEATBALLS ADVENTURES of a CANADIAN COMMUNIST Bert Whyte edited and with an introduction by Larry Hannant Canadian Committee on Labour History Champagne_and_Meatballs_Interior.indd 5 11/01/11 1:45 PM © 2011 Larry Hannant Published by AU Press, Athabasca University 1200, 10011–109 Street Edmonton, AB T5J 3S8 Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Whyte, Bert, 1909–1984 Champagne and meatballs : adventures of a Canadian communist / Bert Whyte ; edited and with an introduction by Larry Hannant. -

Over the Years the Fife Family History Society Journal Has Reviewed Many Published Fife Family Histories

PUBLISHED FAMILY HISTORIES [Over the years The Fife Family History Society Journal has reviewed many published Fife family histories. We have gathered them all together here, and will add to the file as more become available. Many of the family histories are hard to find, but some are still available on the antiquarian market. Others are available as Print on Demand; while a few can be found as Google books] GUNDAROO (1972) By Errol Lea-Scarlett, tells the story of the settlement of the Township of Gundaroo in the centre of the Yass River Valley of NSW, AUS, and the families who built up the town. One was William Affleck (1836-1923) from West Wemyss, described as "Gundaroo's Man of Destiny." He was the son of Arthur Affleck, grocer at West Wemyss, and Ann Wishart, and encourged by letters from the latter's brother, John (Joseph Wiseman) Wishart, the family emigrated to NSW late in October 1854 in the ship, "Nabob," with their children, William and Mary, sole survivors of a family of 13, landing at Sydney on 15 February 1855. The above John Wishart, alias Joseph Wiseman, the son of a Fife merchant, had been convicted of forgery in 1839 and sentenced to 14 years transportation to NSW. On obtaining his ticket of leave in July 1846, he took the lease of the Old Harrow, in which he established a store - the "Caledonia" - and in 1850 added to it a horse-powered mill at Gundaroo some 18 months later. He was the founder of the family's fortunes, and from the 1860s until about 1900 the Afflecks owned most of the commercial buildings in the town. -

Honkif You Want to Sue Lakeside

C M C M Y K Y K THESE LAKERS ARE WINNING FLU SEASON SWOCC men top Umpqua, B1 Boston declares emergency situation, A6 Serving Oregon’s South Coast Since 1878 THURSDAY,JANUARY 10, 2013 theworldlink.com I 75¢ Verger to Honk if you want to sue Lakeside Dems: Don’t lose City fires humility its latest I Former state senator manager urges lawmakers BY DANIEL SIMMONS-RITCHIE toward moderation The World BY TIM NOVOTNY LAKESIDE – It’s déjà vu all over The World again. The city is hunting once more NORTH BEND — Calling it her for a manager after councilors “shot across the bow,” Joanne voted in December to fire their Verger warned state Democrats on newest recruit. Wednesday to remember why they To complicate matters, another have been sent to Salem. key city employee resigned after The longtime Coos Bay politi- eloping with the mayor. cian stepped away from politics City Manager Harry Staven, this year, choosing not to run for formerly from Washington state, re-election in the state Senate. She was terminated by the council in a delivered her remarks to local 5-2 vote after beginning the business leaders at the Bay Area $48,000-per-year position in Chamber of Commerce. August. “It is far too easy to be drunk on Councilor Dean Warner said the sense of importance,”she said. By Alysha Beck, The World Staven appeared to have misled She says politicians have to Genie Corso stands in her Lakeside backyard Wednesday with her pet goose Khloe. The City Council voted to remove Khloe after the council about his abilities. -

00 Cover F.Qxd

22 19 FEATURES CAS Career Achievement Award . 15 Edward J. Greene is this year’s recipient David Hewitt Inducted Into the Hall of Fame. 16 Studio 424 . 19 John Ross builds his home luxury theater Drumming in the Dark. 22 What’s New in Pro Tools 7.2? . 24 David Bondelevitch, CAS, MPSE gives us the lowdown DEPARTMENTS The President’s Letter . 5 16 From the Editors . 7 Technically Speaking . 8 G. John Garrett, CAS discusses radio interference Been There Done That . 29 The members check in The Lighter Side . 38 15 CAS QUARTERLY FALL 2006 3 Welcome to the fourth edition of the CAS Quarterly, which is a smashing success. I would like to thank co-editors Peter Damski, CINEMA AUDIO SOCIETY CAS and Aletha Rodgers, CAS who is stepping down and a MISSION STATEMENT thank-you to David Bondelevitch, CAS, MPSE who will assume Aletha’s responsibilities. You’ve all To educate and inform the general public and the motion done a terrific job! picture and television industry that effective sound is It’s been a great year for the CAS as well. We achieved by a creative, artistic and technical blending of completed the third seminar on Audio Workflow diverse sound elements.To provide the motion picture and From Production Through Post Production and we television industry with a progressive society of master will be releasing the first “white paper” on this craftsmen specialized in the art of creative cinematic subject before year’s end. Just a few weeks ago, sound recording. To advance the specialized field of cine- CAS members and guests were invited to an exclu- THE PRESIDENT’S LETTER sive tour of the spectacular new Warner Brothers matic sound recording by exchange of ideas, methods, and Sound Facilities. -

Failure to Launch: a Study Into the North American Soccer League And

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 8-2008 Failure to Launch: A study into the North American Soccer League and the Women’s United Soccer Association and their factors of failures through Michael Porter’s Models of Strategy Formation Fraser John Boyd University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the Sports Studies Commons Recommended Citation Boyd, Fraser John, "Failure to Launch: A study into the North American Soccer League and the Women’s United Soccer Association and their factors of failures through Michael Porter’s Models of Strategy Formation. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2008. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/3668 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Fraser John Boyd entitled "Failure to Launch: A study into the North American Soccer League and the Women’s United Soccer Association and their factors of failures through Michael Porter’s Models of Strategy Formation." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Master of Science, with a major in Sport Studies. Dr. Damon Andrew, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: Dr. -

DINOSAUR TRACKS: Lost and Found and Lost Again

DINOSAUR TRACKS: Lost and Found and Lost Again FEBRUARY 2006 DudeDude RanchRanch GuideGuide Environmentalist Ranchers NavajoNavajo BullriderBullrider My Heroes Have Always Been CowboysCowboys Lake Powell Grand Canyon Navajo Indian {also inside} National Park Reservation FEBRUARY 2006 2 DEAR EDITOR Greasewood Aubrey Valley Springs 3 ALL WHO WANDER PRESCOTT MAYER Lions or lambs, ranchers or Castle Hot wilderness: Must we choose? Springs Resort Aravaipa My Heroes Have PHOENIX Canyon 26 Portfolio: Long 4 VIEWFINDER Always Been pages 8–24 Grapevine Views to Savor Remembering a mentor. TUCSON Canyon Ranch Photographer Jerry Sieve has gathered 5 TAKING THE OFF-RAMP Huachuca Cowboys Mountains favorite scenic views for 28 years. Explore Arizona oddities, Malpais attractions and pleasures. Borderlands 8 Navajo Rodeo Traditions POINTS OF INTEREST FEATURED IN THIS ISSUE 34 Artist and Man Tracker A multigenerational love of the arena 40 ALONG THE WAY A skilled Indian tracker can hunt down demonstrates the spiritual lessons of a currycomb. The Old West lives on — in a plant shop. bad guys, but art is his real passion. BY LEO W. BANKS PHOTOGRAPHS BY EDWARD MCCAIN BY PAULY HELLER PHOTOGRAPHS BY DAVID HELLER 42 FOCUS ON NATURE 14 Environmentalist Ranchers Feral ferrets cheer, prairie dogs boo. 36 Dinosaur Tracks: Borderland ranchers prove cattle and 44 BACK ROAD ADVENTURE healthy grasslands can coexist. Historic Castle Hot Springs Lost and Found BY TERRY GREENE STERLING A journey through myth and sunlight A photographer races to document stunning PHOTOGRAPHS BY DAVID ZICKL acts as a fountain of youth. trackways before a rising lake drowns them. BY SCOTT THYBONY 48 HIKE OF THE MONTH PHOTOGRAPHS BY ANDRE DELGALVIS 20 Dude Ranch Fantasies Huachuca Mountains’ Perimeter Trail Wannabe cowboys and a cynical writer flutters with butterflies and history. -

Motherless Brooklyn the Irishman Bad Boys for Life

SOCIETY OF CAMERA OPERATORS . WINTER 2020 MOTHERLESS BROOKLYN THE IRISHMAN BAD BOYS FOR LIFE SOC.ORG · WINTER 2020SOC.ORG · VOL. 29, NO.1 STAR WARS: THE RISE OF SKYWALKER CONTENTS DEPARTMENTS FEATURES 4 16 LETTER FROM THE PRESIDENT MOTHERLESS BROOKLYN "Same Place, Different Time" 6 an interview with Craig Haagensen, NEWS & NOTES SOC by Kate McCallum SOC Member David Fredrick 22 Teaches Workshop at AFI, SOC Underwater Camera Operating STAR WARS: THE RISE OF 16 Workshop SKYWALKER 8 "The Force Will Be With You… Always" ESTABLISHING SHOT an interview with Colin Anderson, SOC an interview with Dave Levisohn, by David Daut SOC by Kate McCallum 28 38 THE IRISHMAN THE 2020 SOC LIFETIME "I Heard You Paint Houses" an interview with P. Scott Sakamoto, ACHIEVEMENT AWARDS SOC by Kate McCallum by David Daut 32 42 BAD BOYS FOR LIFE TECH TALK "They’re Back!" "SOC Technical Achievement by Christopher T.J. McGuire, SOC Award 2020: Sony’s VENICE Rialto Extension System" 22 ON THE COVER: BTS; EDWARD NORTON- Lionel Essrog, © 2018 Warner Bros. Entertainment 44 Inc. All Rights Reserved. Photo by Glen Wilson INSIGHT Meet the Members 45 SOC ROSTER 48 SOCIAL SOC 28 32 CAMERA OPERATOR · WINTER 2020 1 Society of Camera Operators OFFICERS Dale Myrand, Benjamin Spek, CONTRIBUTORS Niko Tavernise Dave Thompson, Dan Turrett, Glen Wilson Gary Adock Rob Vuona Board of Governors Colin Anderson, SOC Charities Brian Taylor TRIVIA George Billinger, SOC Membership Drive Lisa Stacilauskas Source imdb.com President George Billinger Peter Cavaciuti, SOC, ACO, Historical Mike Frediani