Stretching Communities of Value Downward, Sideways and Forward

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thornton, Arland. Reading History Sideways: the Fallacy and Enduring Inpact of The

Thornton, Arland. Reading History Sideways: The Fallacy and Enduring Inpact of the Developmental Paradigm on Family Life. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 2005. x, 312 pp.$39 By “reading history sideways,” Arland Thornton means an approach that uses information from a variety of societies at one point in time to make inferences about change over time. He attacks this method as both pervasive and pernicious, influencing scholars, past and present, as well as ordinary people and governments around the world today. A well-known demographer and sociologist, Thornton first set forth his critique to a larger audience in his 2001 presidential address to the Population Association of America (PAA). In his intellectual history of the approach, he absolves Scottish and English writers of the Enlightenment of much blame. Lacking reliable information about the distant past of their own society, authors such as John Millar, Adam Smith, and Robert Malthus seized on data pouring in from European visitors to non-European worlds as a substitute for genuine historical information. Nevertheless, they launched an enduring and fatally flawed perspective. In this book, Thornton concentrates on subjects from his areas of expertise—demographic and family studies—as he criticizes the application of the traditional-to-modern paradigm. In my opinion, Thornton’s reading of the Enlightenment founders is not so much inaccurate as it is single-minded in its emphasis and vague in its documentation. Perhaps because of his narrow, relentless focus, Thornton does not bother to cite page numbers for his sources. In my view, these writers were not principally concerned with setting forth a historical account of change over time. -

Recommended Movies and Television Programs Featuring Psychotherapy and People with Mental Disorders Timothy C

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by OpenKnowledge@NAU Recommended Movies and Television Programs Featuring Psychotherapy and People with Mental Disorders Timothy C. Thomason Abstract This paper provides a list of 200 feature films and five television programs that may be of special interest to counselors, psychologists and other mental health professionals. Many feature characters who portray psychoanalysts, psychiatrists, psychologists, counselors, or psychotherapists. Many of them also feature characters who have, or may have, mental disorders. In addition to their entertainment value, these videos can be seen as fictional case studies, and counselors can practice diagnosing the disorders of the characters and consider whether the treatments provided are appropriate. It can be both educational and entertaining for counselors, psychologists, and others to view films that portray psychotherapists and people with mental disorders. It should be noted that movies rarely depict either therapists or people with mental disorders in an accurate manner (Ramchandani, 2012). Most movies are made for entertainment value rather than educational value. For example, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest is a wonderfully entertaining Academy Award-winning film, but it contains a highly inaccurate portrayal of electroconvulsive therapy. It can be difficult or impossible for a viewer to ascertain the disorder of characters in movies, since they are not usually realistic portrayals of people with mental disorders. Likewise, depictions of mental health professionals in the movies are usually very exaggerated or distorted, and often include behaviors that would be considered violations of professional ethical standards. Even so, psychology students and psychotherapists may find some of these movies interesting as examples of what not to do. -

A Mass Media-Centered Approach to Teaching the Course in Family Communication. INSTITUTION National Communication Association, Annandale, VA

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 439 463 CS 510 274 AUTHOR Mackey-Kallis, Susan; Kirk-Elfenbein, Sharon TITLE A Mass Media-Centered Approach to Teaching the Course in Family Communication. INSTITUTION National Communication Association, Annandale, VA. PUB DATE 1997-00-00 NOTE 17p. AVAILABLE FROM For full text: http://www.natcom.org/ctronline2/96-97mas.htm. PUB TYPE Opinion Papers (120) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Family Relationship; *Family (Sociological Unit); *Films; Higher Education; Mass Media Effects; Mass Media Role; Programming (Broadcast); *Television IDENTIFIERS *Family Communication ABSTRACT Teaching family communication is unique. However, unlike courses in small group and interpersonal communication, which illustrates communication processes in experiential settings, family communication courses cannot create "families" in the classroom. As such, film and television depictions of the family become all the more important in their ability to illustrate key concepts of family communication theory while providing common experiences for classroom discussion. Accordingly, this paper has two purposes:(1) to inform and affirm the ways in which films and television programming can be used to illustrate significant family concepts, relationships, and issues in family communication courses; and (2) to demonstrate how the examination of media families helps students to learn more about culture's representation of this most important social institution. After exploring the impact of mass media portrayals of families, the paper discusses ways in which such films as "Ordinary People," "Terms of Endearment," "On Golden Pond," and "Frances" can be used to teach various family communication concepts and topics. The use of films' and television shows' depictions of the family in a course stimulates students to take a closer look at their own families and themselves, and to understand how mass mediated images of the family shape their own expectations of family life. -

On-The-Waterfront-Study-Guide

On the Waterfront Study Guide Acknowledgements Writer: Susan Bye Education Programmer Australian Centre for the Moving Image Susan’s primary role at the Australian Centre for the Moving Image is to support the teaching of film as text to secondary school students. Initially trained as an English teacher, she studied and taught film and media at La Trobe University before joining ACMI in 2009. Study Guide > On the Waterfront 2 On the Waterfront: difficult choices in an uncertain world The purpose of this guide is to provide an introduction to On the Waterfront (PG, Elia Kazan, 103 mins, USA, 1954), an overview of the commentary and debate that the film has generated and some ideas that will help you form your own interpretation of this challenging film. Studying and Interpreting On the Waterfront On the Waterfront is a film that is as problematic as it is extraordinary. It carries with it an interesting history which has, over the years, affected the way people have responded to the film. On the Waterfront encourages different and conflicting interpretations, with its controversial ending being a particular source of debate. This study guide is intended as an informative resource, providing background information and a number of different ways of thinking about the film. One of the most exciting and satisfying aspects of the film is its capacity to invite and sustain different and multifaceted interpretations. On the Waterfront focuses on life’s uncertainty and confusion, depicting both Father Barry’s dogmatic certainty and Johnny Friendly’s egotistical self-confidence as dangerously blinkered. For some viewers, Father Barry’s vision of collective action and Terry Malloy’s confused struggle to be a better man belong in two different films; however, the contrast between these two ways of looking at, and responding to, life’s challenges highlights the limitations of each of these perspectives. -

July 4, 2021 the Fourteenth Sunday in Ordinary Time Parish Office

July 4, 2021 The Fourteenth Sunday in Ordinary Time Parish Office Pastor 6673 West Chatfield Avenue • Littleton, CO 80128 Rev. John Paul Leyba www.sfcparish.org Parochial Vicars 303-979-7688 Parish Office Rev. Israel Gonsalves, O.C.D. Open: Monday-Friday, 8:30am-5:00pm Rev. Ron Sequeira, O.C.D. (closed 12:00 noon-1:00pm daily) 303-979-7688 Voice mail access after 5:00pm 303-953-7777 Youth Office (Jr. & Sr. High, Young Adult) Deacons 303-972-8566 Fax Line Rev. Mr. Chet Ubowski 303-979-7688 SACRAMENTAL EMERGENCIES Rev. Mr. Marc Nestorick 24 hrs/day Rev. Mr. Brian Kerby St. Frances303-953-7770 Cabrini Weather/Emergency Hotline Rev. Mr. Spencer Thornber (for schedule changes due to inclement Rev. Mr. Paul Grimm (retired) weather/emergency situations) Rev. Mr. Witold Engel (retired) Welcome to Our Parish! We are glad you are here! If you are a visitor and would like to join our parish family, please pick up a registration form in the gathering space, visit the parish office during the week or you may visit our website to register. Sacramental Information Mass Schedule Infant Baptism: Please contact Deacon Chet at 303-953-7783. Weekend ... Saturday (Anticipatory) 4:15 pm; Sunday 7:15, 9:15, 11:15am & 5:15pm Marriage Preparation: Please contact Trudy at 303-953-7769 at Weekday .............. Monday-Friday 9:00 am; least 9-12 months prior to your wedding to make arrangements. Mon., Tues., Thurs., Fri. 6:30am RCIA: Interested in becoming Catholic or questions about the faith? First Saturday .............................. 10:00am Call Deacon Chet at 303-953-7783. -

The Return of the 1950S Nuclear Family in Films of the 1980S

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2011 The Return of the 1950s Nuclear Family in Films of the 1980s Chris Steve Maltezos University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons, and the Film and Media Studies Commons Scholar Commons Citation Maltezos, Chris Steve, "The Return of the 1950s Nuclear Family in Films of the 1980s" (2011). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/3230 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Return of the 1950s Nuclear Family in Films of the 1980s by Chris Maltezos A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Liberal Arts Department of Humanities College Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Daniel Belgrad, Ph.D. Elizabeth Bell, Ph.D. Margit Grieb, Ph.D. Date of Approval: March 4, 2011 Keywords: Intergenerational Relationships, Father Figure, insular sphere, mother, single-parent household Copyright © 2011, Chris Maltezos Dedication Much thanks to all my family and friends who supported me through the creative process. I appreciate your good wishes and continued love. I couldn’t have done this without any of you! Acknowledgements I’d like to first and foremost would like to thank my thesis advisor Dr. -

Needs of a Person Who Suffered from Autism As Portrayed in Winston Groom’S Forrest Gump

NEEDS OF A PERSON WHO SUFFERED FROM AUTISM AS PORTRAYED IN WINSTON GROOM’S FORREST GUMP A THESIS BY: TEGUH PERDANA DAMANIK REG.NO. 140705010 DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH FACULTY OF CULTURAL STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF SUMATERA UTARA MEDAN 2018 UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA NEEDS OF A PERSON WHO SUFFERED FROM AUTISM AS PORTRAYED IN WINSTON GROOM’S FORREST GUMP A THESIS BY TEGUH PERDANA DAMANIK REG. NO. 140705010 SUPERVISOR CO-SUPERVISOR Drs. Parlindungan Purba, M.Hum. Riko Andika Rahmat Pohan, S.S., M.Hum. NIP. 19630216 198903 1 003 NIP. 19580517198503 1 003 Submitted to Faculty of Cultural Studies University of Sumatera Utara Medan i n partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Sarjana Sastra from Department of English. DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH FACULTY OF CULTURAL STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF SUMATERA UTARA MEDAN 2018 UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA Approved by the Department of English, Faculty of Cultural Studies, University of Sumatera Utara (USU) Medan as thesis for The Sarjana Sastra Examination. Head Secretary Prof. T. Silvana Sinar, M. A., Ph. D Rahmadsyah Rangkuti, M.A., Ph. D. NIP. 19540916 198003 2 003 NIP. 19750209 200812 1 002 UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA Accepted by the Board of Examiners in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Sarjana Sastra from the Department of English, Faculty of Cultural Studies University of Sumatera Utara, Medan. The examination is held in Department of English Faculty of Cultural Studies University of Sumatera Utara on 15th August 2018 Dean of Faculty of Cultural Studies University of Sumatera Utara Dr. Budi Agustono, M.S. NIP. 19600805 198703 1 001 Board of Examiners Rahmadsyah Rangkuti, M.A., Ph.D. -

Ordinary People Press

ORDINARY PEOPLE Writer/director Dr. Jennifer Rutherford Producer Martha Ansara Film Australia Executive Producer Stefan Moore A FILM AUSTRALIA NATIONAL INTEREST PROGRAM PRODUCED WITH THE ASSISTANCE OF THE AUSTRALIAN FILM COMMISSION, THE NEW SOUTH WALES FILM AND TELEVISION OFFICE AND THE AUSTRALIAN BROADCASTING CORPORATION. © Film Australia ORDINARY PEOPLE SYNOPSIS Far right and anti-immigration politics are on the rise worldwide. In Australia, as in many other western countries, a new political force is drawing on the discontent of those who feel excluded from the promised benefits of globalisation. Rejecting the new world order and its transformation of their economies and cultures, these people are convinced that traditional political parties no longer represent them or their interests. They are desperate to make their voice heard. For Colene Hughes and her supporters, Pauline Hanson’s One Nation Party initially appears to offer a solution. It seems to promise true democracy, a way of knocking the country back into shape - giving people like them some power again. However, over time, their belief in the moral rightness of One Nation is confronted by the realities of the party’s internal politics. Once Colene starts to question the authoritarian control of the party’s executive members, the gloves come off. At the annual general meeting, the two forces collide. This revealing documentary follows Colene through two years and two election campaigns as a One Nation candidate in Ipswich, Queensland, heartland of One Nation. It travels with her on the campaign trail as her idealistic fervour slowly turns to disillusionment. It also gives the viewer an unparalleled look at One Nation - from the inside. -

A-Force-More-Powerful-Study-Guide

Production Credits Educational Outreach Advisors Written, Produced and Directed by: Steve York Dr. Kevin Clements, International Alert, London, England Narrated by: Ben Kingsley Martharose Laffey, former Executive Director, National Series Editor and Principal Content Advisor: Council for the Social Studies, Washington, D.C. Peter Ackerman Joanne Leedom-Ackerman, former Chair, Managing Producer: Miriam A. Zimmerman Writers in Prison Committee, International PEN Sheilah Mann, Director of Educational Affairs, Editors: Joseph Wiedenmayer and David Ewing American Political Science Association, Washington, D.C. Executive Producer: Jack DuVall Doug McAdam, Center for Advanced Study Senior Production Executives for WETA: in the Behavioral Sciences, Stanford University Richard Thomas, Polly Wells and Laurie Rackas Sidney Tarrow, Maxwell M. Upson Executive-in-Charge of Production: Dalton Delan Professor of Government, Cornell University Outreach/Study Guide Educational materials for A Force More Powerful: Writer: Jonathan Mogul A Century of Nonviolent Conflict were developed Editor: Barbara de Boinville in association with Toby Levine Communications, Inc., Potomac, Maryland. Project Staff, WETA Senior Vice President, Strategic Projects: To order the companion book, A Force More Francine Zorn Trachtenberg Powerful: A Century of Nonviolent Conflict, Project Manager, Educational Services by Peter Ackerman and Jack DuVall, call St. Martin’s & Outreach: Karen Zill Press at 1-800-221-7945, ext. 270. You will receive a Art Director: Cynthia Aldridge 20% discount when you order with a major credit card. Administrative Coordinator: Susi Crespo Intern: Justine Nelson Video Distribution To order videocassettes of the two 90-minute programs Web Development, WETA for home use, or the six 30-minute modules Director, Interactive Media: Walter Rissmeyer for educational/institutional use, please contact: Manager, Interactive Media: John R. -

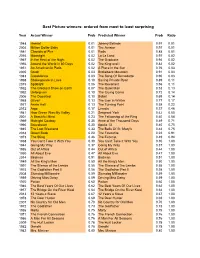

Best Picture Winners: Ordered from Most to Least Surprising

Best Picture winners: ordered from most to least surprising Year Actual Winner Prob Predicted Winner Prob Ratio 1948 Hamlet 0.01 Johnny Belinda 0.97 0.01 2004 Million Dollar Baby 0.01 The Aviator 0.97 0.01 1981 Chariots of Fire 0.01 Reds 0.88 0.01 2016 Moonlight 0.02 La La Land 0.97 0.02 1967 In the Heat of the Night 0.02 The Graduate 0.94 0.02 1956 Around the World in 80 Days 0.02 The King and I 0.82 0.02 1951 An American in Paris 0.02 A Place in the Sun 0.76 0.03 2005 Crash 0.03 Brokeback Mountain 0.91 0.03 1943 Casablanca 0.03 The Song Of Bernadette 0.90 0.03 1998 Shakespeare in Love 0.10 Saving Private Ryan 0.89 0.11 2015 Spotlight 0.06 The Revenant 0.56 0.11 1952 The Greatest Show on Earth 0.07 The Quiet Man 0.53 0.13 1992 Unforgiven 0.10 The Crying Game 0.72 0.14 2006 The Departed 0.10 Babel 0.69 0.14 1968 Oliver! 0.13 The Lion in Winter 0.77 0.17 1977 Annie Hall 0.13 The Turning Point 0.58 0.22 2012 Argo 0.17 Lincoln 0.37 0.46 1941 How Green Was My Valley 0.21 Sergeant York 0.42 0.50 2001 A Beautiful Mind 0.23 The Fellowship of the Ring 0.40 0.58 1969 Midnight Cowboy 0.35 Anne of the Thousand Days 0.49 0.71 1995 Braveheart 0.30 Apollo 13 0.40 0.75 1945 The Lost Weekend 0.33 The Bells Of St. -

Ambivalence As a Theme in "On the Waterfront" (1954): an Interdisciplinary Approach to Film Study Author(S): Kenneth Hey Source: American Quarterly, Vol

Ambivalence as a Theme in "On the Waterfront" (1954): An Interdisciplinary Approach to Film Study Author(s): Kenneth Hey Source: American Quarterly, Vol. 31, No. 5, Special Issue: Film and American Studies (Winter, 1979), pp. 666-696 Published by: The Johns Hopkins University Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2712431 Accessed: 02/07/2010 10:41 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=jhup. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The Johns Hopkins University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to American Quarterly. http://www.jstor.org AMBIVALENCE AS A THEME IN ON THE WATERFRONT (1954): AN INTERDISCIPLINARY APPROACH TO FILM STUDY KENNETH HEY BrooklynCollege of theCity University of New York THE STUDY OF FILM IN AMERICAN CULTURE POSES SOME INTERESTING challengesto theperson using an interdisciplinarymethod. -

Raging Bull (1980)

The Buffalo Film Seminars 4/19/2000 Angelika 8 Theater RAGING BULL (1980) Director Martin Scorsese Producers Robert Chartoff and Irwin Winkler Music Robbie Robertson and Pietro Mascagni Cinematographer Michael Chapman Film Editor Thelma Schoonmaker Sound Best David J. Kimball, Les Lazarowitz, Donald O. Mitchell and Bill Nicholson. Script Paul Schrader and Mardik Martin (the shooting script was by Scorsese and De Niro), loosely based on the book by Jake LaMotta, Joseph Carter& Peter Savage Robert De Niro Jake La Motta Frank Topham Toppy Cathy Moriarty Vickie La Motta Charles Scorsese Charlie - Man with Como Joe Pesci Joey La Motta Don Dunphy Himself/Radio Announcer Frank Vincent Salvy Bill Hanrahan Eddie Eagan Nicholas Colasanto Tommy Como Rita Bennett Emma - Miss 48's Theresa Saldana Lenore Johnny Barnes Sugar Ray Robinson Mario Gallo Mario Louis R aftis Marcel Cerdan Frank Adonis Patsy Johnny Turner Laurent Dauthuille Joseph Bono Guido Martin Scorsese Barbizon Stagehand De Niro and Schoonmaker won Academy Awards for this picture and nominations went to Scorsese, Chapman, Chartoff and Winkler, Pesci, Moriarty, and the four sound editors. The Awards for best director and best picture that year went to Ordinary People directed b y Robert R edford. Raging Bull is on the American Film Institute’s list of 100 Greatest American Films and has frequently been listed as the best film of the 1980s; Ordinary People hasn’t made either list. MARTIN SCORSESE was going to be a priest but beca me a filmmaker instead. He’s a 1 964 gradu ate of the NYU film program . In 1997 he received the American Film Institute Life Achievement Award.