Identity and Otherness in Forrest Gump: a Close-Up Into Twentieth-Century America

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Supplemental Movies and Movie Clips

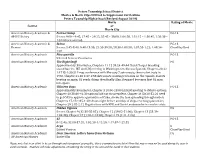

Peters Township School District Movies & Movie Clips Utilized to Supplement Curriculum Peters Township High School (Revised August 2019) Movie Rating of Movie Course or Movie Clip American History Academic & Forrest Gump PG-13 AP US History Scenes 9:00 – 9:45, 27:45 – 29:25, 35:45 – 38:00, 1:06:50, 1:31:15 – 1:30:45, 1:50:30 – 1:51:00 are omitted. American History Academic & Selma PG-13 Honors Scenes 3:45-8:40; 9:40-13:30; 25:50-39:50; 58:30-1:00:50; 1:07:50-1:22; 1:48:54- ClearPlayUsed 2:01 American History Academic Pleasantville PG-13 Selected Scenes 25 minutes American History Academic The Right Stuff PG Approximately 30 minutes, Chapters 11-12 39:24-49:44 Chuck Yeager breaking sound barrier, IKE and LBJ meeting in Washington to discuss Sputnik, Chapters 20-22 1:1715-1:30:51 Press conference with Mercury 7 astronauts, then rocket tests in 1960, Chapter 24-30 1:37-1:58 Astronauts wanting revisions on the capsule, Soviets beating us again, US sends chimp then finally Alan Sheppard becomes first US man into space American History Academic Thirteen Days PG-13 Approximately 30 minutes, Chapter 3 10:00-13:00 EXCOM meeting to debate options, Chapter 10 38:00-41:30 options laid out for president, Chapter 14 50:20-52:20 need to get OAS to approve quarantine of Cuba, shows the fear spreading through nation, Chapters 17-18 1:05-1:20 shows night before and day of ships reaching quarantine, Chapter 29 2:05-2:12 Negotiations with RFK and Soviet ambassador to resolve crisis American History Academic Hidden Figures PG Scenes Chapter 9 (32:38-35:05); -

P20-21.Qxp Layout 1

20 Friday Friday, March 15, 2019 Lifestyle | Music and Movies Director Kusturica named advisor to Bosnia’s Serb president cclaimed Serbian filmmaker Emir Kusturica has West, Dodik later rebranded as a firebrand nationalist. been appointed an advisor to Bosnia’s nationalist In recent years he inflamed Western powers by referring ASerb President Milorad Dodik, according to the to post-war Bosnia as a “failed country” and threatening presidency. The two men are known to be close friends, to hold a referendum on the secession of the Serb-dom- with 64-year-old Kusturica, a two-time Palme d’Or win- inated region he has run for a decade. Kusturica, who ner, describing Dodik as “nothing but the best” in an in- was born in Sarajevo but has not returned since the terview last year with local media. The announcement, 1992-95 war, is also known for provocative views. One posted on the presidency’s website, did not specify what of his Palme d’Or films, “Underground” (1995), was ac- Kusturica’s portfolio would be. Dodik, who has been cused by critics of being too pro-Serb. Nearly a quarter sanctioned by the US, was elected to Bosnia’s three-man century after the conflict that killed 100,000 people, presidency last October, seeding fears about the future Bosnia remains divided along communal lines, with of the fragile and divided country. power shared between Serb, Muslim and Croat con- Though he began his political career as an ally of the stituencies. —AFP Aamir Khan to star in Joss Stone plays ‘unofficial gig’ in North Korea Bollywood ‘Forrest Gump’ remake ollywood megastar Aamir Khan announced yester- day that he is to star in an official Hindi-language re- Bmake of hit American movie “Forrest Gump”. -

Thornton, Arland. Reading History Sideways: the Fallacy and Enduring Inpact of The

Thornton, Arland. Reading History Sideways: The Fallacy and Enduring Inpact of the Developmental Paradigm on Family Life. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 2005. x, 312 pp.$39 By “reading history sideways,” Arland Thornton means an approach that uses information from a variety of societies at one point in time to make inferences about change over time. He attacks this method as both pervasive and pernicious, influencing scholars, past and present, as well as ordinary people and governments around the world today. A well-known demographer and sociologist, Thornton first set forth his critique to a larger audience in his 2001 presidential address to the Population Association of America (PAA). In his intellectual history of the approach, he absolves Scottish and English writers of the Enlightenment of much blame. Lacking reliable information about the distant past of their own society, authors such as John Millar, Adam Smith, and Robert Malthus seized on data pouring in from European visitors to non-European worlds as a substitute for genuine historical information. Nevertheless, they launched an enduring and fatally flawed perspective. In this book, Thornton concentrates on subjects from his areas of expertise—demographic and family studies—as he criticizes the application of the traditional-to-modern paradigm. In my opinion, Thornton’s reading of the Enlightenment founders is not so much inaccurate as it is single-minded in its emphasis and vague in its documentation. Perhaps because of his narrow, relentless focus, Thornton does not bother to cite page numbers for his sources. In my view, these writers were not principally concerned with setting forth a historical account of change over time. -

Recommended Movies and Television Programs Featuring Psychotherapy and People with Mental Disorders Timothy C

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by OpenKnowledge@NAU Recommended Movies and Television Programs Featuring Psychotherapy and People with Mental Disorders Timothy C. Thomason Abstract This paper provides a list of 200 feature films and five television programs that may be of special interest to counselors, psychologists and other mental health professionals. Many feature characters who portray psychoanalysts, psychiatrists, psychologists, counselors, or psychotherapists. Many of them also feature characters who have, or may have, mental disorders. In addition to their entertainment value, these videos can be seen as fictional case studies, and counselors can practice diagnosing the disorders of the characters and consider whether the treatments provided are appropriate. It can be both educational and entertaining for counselors, psychologists, and others to view films that portray psychotherapists and people with mental disorders. It should be noted that movies rarely depict either therapists or people with mental disorders in an accurate manner (Ramchandani, 2012). Most movies are made for entertainment value rather than educational value. For example, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest is a wonderfully entertaining Academy Award-winning film, but it contains a highly inaccurate portrayal of electroconvulsive therapy. It can be difficult or impossible for a viewer to ascertain the disorder of characters in movies, since they are not usually realistic portrayals of people with mental disorders. Likewise, depictions of mental health professionals in the movies are usually very exaggerated or distorted, and often include behaviors that would be considered violations of professional ethical standards. Even so, psychology students and psychotherapists may find some of these movies interesting as examples of what not to do. -

The Hobbit the Desolation of Smaug the Quest for Erbor / the Forest River / the Hunters / Beyond the Forest

The Hobbit The Desolation Of Smaug The Quest For Erbor / The Forest River / The Hunters / Beyond The Forest Brass Band Arr.: Jirka Kadlec Adapt.: Bertrand Moren Howard Shore EMR 9842 st + 1 Full Score 2 1 B Trombone nd + 1 E Cornet 2 2 B Trombone + 5 Solo B Cornet 1 B Bass Trombone 1 Repiano Cornet 2 Euphonium nd 3 2 B Cornet 3 E Bass rd 3 3 B Cornet 3 B Bass 1 B Flugelhorn 1 Timpani st 2 Solo E Horn 1 1 Percussion (Tubular Bells / Glockenspiel) st nd 2 1 E Horn 1 2 Percussion (Suspended Cymbal) nd rd 2 2 E Horn 1 3 Percussion (Triangle / Drum Set) st 2 1 B Baritone nd 2 2 B Baritone Print & Listen Drucken & Anhören Imprimer & Ecouter ! www.reift.ch Route du Golf 150 ! CH-3963 Crans-Montana (Switzerland) Tel. +41 (0) 27 483 12 00 ! Fax +41 (0) 27 483 42 43 ! E-Mail : [email protected] ! www.reift.ch DISCOGRAPHY Cinemagic 47 Track Titel / Title Time N° EMR N° EMR N° (Komponist / Composer) Blasorchester Brass Band Concert Band 1 The Incredibles (Giacchino) 6’00 EMR 12185 EMR 9667 2 Concerto De L’Adieu (Delerue) 9’57 EMR 12277 EMR 9837 3 Tombstone (Broughton) 7’37 EMR 12245 EMR 9838 4 Jaws: The Revenge (Small) 3’48 EMR 12191 EMR 9839 5 The Croods (Silvestri) 4’38 EMR 12258 EMR 9840 6 Rise Of The Guardians (Desplat) 7’40 EMR 12234 EMR 9763 7 The Karate Kid (Horner) 9’00 EMR 12238 EMR 9841 8 The Hobbit (The Desolation Of Smaug) (Shore) 4’17 EMR 12261 EMR 9842 Zu bestellen bei • A commander chez • To be ordered from: Editions Marc Reift • Route du Golf 150 • CH-3963 Crans-Montana (Switzerland) • Tel. -

A Mass Media-Centered Approach to Teaching the Course in Family Communication. INSTITUTION National Communication Association, Annandale, VA

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 439 463 CS 510 274 AUTHOR Mackey-Kallis, Susan; Kirk-Elfenbein, Sharon TITLE A Mass Media-Centered Approach to Teaching the Course in Family Communication. INSTITUTION National Communication Association, Annandale, VA. PUB DATE 1997-00-00 NOTE 17p. AVAILABLE FROM For full text: http://www.natcom.org/ctronline2/96-97mas.htm. PUB TYPE Opinion Papers (120) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Family Relationship; *Family (Sociological Unit); *Films; Higher Education; Mass Media Effects; Mass Media Role; Programming (Broadcast); *Television IDENTIFIERS *Family Communication ABSTRACT Teaching family communication is unique. However, unlike courses in small group and interpersonal communication, which illustrates communication processes in experiential settings, family communication courses cannot create "families" in the classroom. As such, film and television depictions of the family become all the more important in their ability to illustrate key concepts of family communication theory while providing common experiences for classroom discussion. Accordingly, this paper has two purposes:(1) to inform and affirm the ways in which films and television programming can be used to illustrate significant family concepts, relationships, and issues in family communication courses; and (2) to demonstrate how the examination of media families helps students to learn more about culture's representation of this most important social institution. After exploring the impact of mass media portrayals of families, the paper discusses ways in which such films as "Ordinary People," "Terms of Endearment," "On Golden Pond," and "Frances" can be used to teach various family communication concepts and topics. The use of films' and television shows' depictions of the family in a course stimulates students to take a closer look at their own families and themselves, and to understand how mass mediated images of the family shape their own expectations of family life. -

On-The-Waterfront-Study-Guide

On the Waterfront Study Guide Acknowledgements Writer: Susan Bye Education Programmer Australian Centre for the Moving Image Susan’s primary role at the Australian Centre for the Moving Image is to support the teaching of film as text to secondary school students. Initially trained as an English teacher, she studied and taught film and media at La Trobe University before joining ACMI in 2009. Study Guide > On the Waterfront 2 On the Waterfront: difficult choices in an uncertain world The purpose of this guide is to provide an introduction to On the Waterfront (PG, Elia Kazan, 103 mins, USA, 1954), an overview of the commentary and debate that the film has generated and some ideas that will help you form your own interpretation of this challenging film. Studying and Interpreting On the Waterfront On the Waterfront is a film that is as problematic as it is extraordinary. It carries with it an interesting history which has, over the years, affected the way people have responded to the film. On the Waterfront encourages different and conflicting interpretations, with its controversial ending being a particular source of debate. This study guide is intended as an informative resource, providing background information and a number of different ways of thinking about the film. One of the most exciting and satisfying aspects of the film is its capacity to invite and sustain different and multifaceted interpretations. On the Waterfront focuses on life’s uncertainty and confusion, depicting both Father Barry’s dogmatic certainty and Johnny Friendly’s egotistical self-confidence as dangerously blinkered. For some viewers, Father Barry’s vision of collective action and Terry Malloy’s confused struggle to be a better man belong in two different films; however, the contrast between these two ways of looking at, and responding to, life’s challenges highlights the limitations of each of these perspectives. -

July 4, 2021 the Fourteenth Sunday in Ordinary Time Parish Office

July 4, 2021 The Fourteenth Sunday in Ordinary Time Parish Office Pastor 6673 West Chatfield Avenue • Littleton, CO 80128 Rev. John Paul Leyba www.sfcparish.org Parochial Vicars 303-979-7688 Parish Office Rev. Israel Gonsalves, O.C.D. Open: Monday-Friday, 8:30am-5:00pm Rev. Ron Sequeira, O.C.D. (closed 12:00 noon-1:00pm daily) 303-979-7688 Voice mail access after 5:00pm 303-953-7777 Youth Office (Jr. & Sr. High, Young Adult) Deacons 303-972-8566 Fax Line Rev. Mr. Chet Ubowski 303-979-7688 SACRAMENTAL EMERGENCIES Rev. Mr. Marc Nestorick 24 hrs/day Rev. Mr. Brian Kerby St. Frances303-953-7770 Cabrini Weather/Emergency Hotline Rev. Mr. Spencer Thornber (for schedule changes due to inclement Rev. Mr. Paul Grimm (retired) weather/emergency situations) Rev. Mr. Witold Engel (retired) Welcome to Our Parish! We are glad you are here! If you are a visitor and would like to join our parish family, please pick up a registration form in the gathering space, visit the parish office during the week or you may visit our website to register. Sacramental Information Mass Schedule Infant Baptism: Please contact Deacon Chet at 303-953-7783. Weekend ... Saturday (Anticipatory) 4:15 pm; Sunday 7:15, 9:15, 11:15am & 5:15pm Marriage Preparation: Please contact Trudy at 303-953-7769 at Weekday .............. Monday-Friday 9:00 am; least 9-12 months prior to your wedding to make arrangements. Mon., Tues., Thurs., Fri. 6:30am RCIA: Interested in becoming Catholic or questions about the faith? First Saturday .............................. 10:00am Call Deacon Chet at 303-953-7783. -

Exploring Films About Ethical Leadership: Can Lessons Be Learned?

EXPLORING FILMS ABOUT ETHICAL LEADERSHIP: CAN LESSONS BE LEARNED? By Richard J. Stillman II University of Colorado at Denver and Health Sciences Center Public Administration and Management Volume Eleven, Number 3, pp. 103-305 2006 104 DEDICATED TO THOSE ETHICAL LEADERS WHO LOST THEIR LIVES IN THE 9/11 TERROIST ATTACKS — MAY THEIR HEORISM BE REMEMBERED 105 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface 106 Advancing Our Understanding of Ethical Leadership through Films 108 Notes on Selecting Films about Ethical Leadership 142 Index by Subject 301 106 PREFACE In his preface to James M cG regor B urns‘ Pulitzer–prizewinning book, Leadership (1978), the author w rote that ―… an im m ense reservoir of data and analysis and theories have developed,‖ but ―w e have no school of leadership.‖ R ather, ―… scholars have worked in separate disciplines and sub-disciplines in pursuit of different and often related questions and problem s.‖ (p.3) B urns argued that the tim e w as ripe to draw together this vast accumulation of research and analysis from humanities and social sciences in order to arrive at a conceptual synthesis, even an intellectual breakthrough for understanding of this critically important subject. Of course, that was the aim of his magisterial scholarly work, and while unquestionably impressive, his tome turned out to be by no means the last word on the topic. Indeed over the intervening quarter century, quite to the contrary, we witnessed a continuously increasing outpouring of specialized political science, historical, philosophical, psychological, and other disciplinary studies with clearly ―no school of leadership‖with a single unifying theory emerging. -

The Piano Duet Play-Along Series Gives You the • I Dreamed a Dream • in My Life • on My Own • Stars

1. Piano Favorites 13. Movie Hits 9 great duets: Candle in the Wind • Chopsticks • Don’t 8 film favorites: Theme from E.T. (The Extra-Terrestrial) Know Why • Edelweiss • Goodbye Yellow Brick Road • • Forrest Gump – Main Title (Feather Theme) • The Heart and Soul • Let It Be • Linus and Lucy • Your Song. Godfather (Love Theme) • The John Dunbar Theme • Moon 00290546 Book/CD Pack ............................$14.95 River • Romeo and Juliet (Love Theme) • Theme from Schindler’s List • Somewhere, My Love. 2. Movie Favorites 00290560 Book/CD Pack ...........................$14.95 8 classics: Chariots of Fire • The Entertainer • Theme from Jurassic Park • My Father’s Favorite • My Heart Will Go 14. Les Misérables On (Love Theme from Titanic) • Somewhere in Time • 8 great songs from the musical: Bring Him Home • Castle on Somewhere, My Love • Star Trek® the Motion Picture. a Cloud • Do You Hear the People Sing? • A Heart Full of Love The Piano Duet Play-Along series gives you the • I Dreamed a Dream • In My Life • On My Own • Stars. flexibility to rehearse or perform piano duets 00290547 Book/CD Pack ............................$14.95 00290561 Book/CD Pack ...........................$16.95 anytime, anywhere! Play these delightful tunes 3. Broadway for Two 10 songs from the stage: Any Dream Will Do • Blue Skies 15. God Bless America® & Other with a partner, or use the accompanying CDs • Cabaret • Climb Ev’ry Mountain • If I Loved You • Okla- to play along with either the Secondo or Primo Songs for a Better Nation homa • Ol’ Man River • On My Own • There’s No Business 8 patriotic duets: America, the Beautiful • Anchors part on your own. -

Holy Fools, Secular Saints, and Illiterate Saviors in American Literature and Popular Culture

CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture ISSN 1481-4374 Purdue University Press ©Purdue University Volume 5 (2003) Issue 3 Article 4 Holy Fools, Secular Saints, and Illiterate Saviors in American Literature and Popular Culture Dana Heller Old Dominion University Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/clcweb Part of the Comparative Literature Commons, and the Critical and Cultural Studies Commons Dedicated to the dissemination of scholarly and professional information, Purdue University Press selects, develops, and distributes quality resources in several key subject areas for which its parent university is famous, including business, technology, health, veterinary medicine, and other selected disciplines in the humanities and sciences. CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture, the peer-reviewed, full-text, and open-access learned journal in the humanities and social sciences, publishes new scholarship following tenets of the discipline of comparative literature and the field of cultural studies designated as "comparative cultural studies." Publications in the journal are indexed in the Annual Bibliography of English Language and Literature (Chadwyck-Healey), the Arts and Humanities Citation Index (Thomson Reuters ISI), the Humanities Index (Wilson), Humanities International Complete (EBSCO), the International Bibliography of the Modern Language Association of America, and Scopus (Elsevier). The journal is affiliated with the Purdue University Press monograph series of Books in Comparative Cultural Studies. Contact: <[email protected]> Recommended Citation Heller, Dana. "Holy Fools, Secular Saints, and Illiterate Saviors in American Literature and Popular Culture." CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture 5.3 (2003): <https://doi.org/10.7771/1481-4374.1193> This text has been double-blind peer reviewed by 2+1 experts in the field. -

Forrest Gump

LEVEL 3 Answer keys Teacher Support Programme Forrest Gump Book key e is an idiot 1 a jungle b banana c boiler d harmonica f the jungle e helicopter f net g working at the Temperer factory in Indianapolis 2 a The story of America from the 1960s to the 1990s. h arm-wrestling in a bar b Winston Groom also grew up in Mobile, Alabama, i purposely and fought in the Vietnam war. 16–17 Open answers 3 a, c, f and g are right. 18 a ✗ – He wins. 4 a Coach Fellers, to the high school head teacher b ✗ – She shouts and screams. b the police, to Forrest’s mother c ✓ c Forrest’s mother, to the police or Mrs Curran d ✓ d Curtis, to a friend e ✗ – He makes lots of money and employs four e Bubba, to a friend people. f Jenny, to a friend f ✓ 5 Open answers g ✓ 6 a Weasel makes a mistake and they lose the game. 19 a Forrest plays chess with Mr Tribble. b Bubba puts Forrest on the bus to Mobile. b Forrest gets a part in a film. c Forrest cooks for all the men at Fort Benning. c Forrest stops playing chess for money. d Jenny pays Forrest to play the harmonica. d Bubba’s father helps Forrest to start his shrimp e Coach Bryant has taught Forrest to catch the business. football. 20 Open answers f Forrest’s mother cries because Forrest joins the 21 a Forrest to Sue b Jenny to Little Forrest army. c Forrest to Jenny d Little Forrest to Jenny 7 a Nobody.