"I Will Have to Look at Him"| an Ecocritique of Faulkner's "The Bear"

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

L'équipe Des Scénaristes De Lost Comme Un Auteur Pluriel Ou Quelques Propositions Méthodologiques Pour Analyser L'auctorialité Des Séries Télévisées

Lost in serial television authorship : l’équipe des scénaristes de Lost comme un auteur pluriel ou quelques propositions méthodologiques pour analyser l’auctorialité des séries télévisées Quentin Fischer To cite this version: Quentin Fischer. Lost in serial television authorship : l’équipe des scénaristes de Lost comme un auteur pluriel ou quelques propositions méthodologiques pour analyser l’auctorialité des séries télévisées. Sciences de l’Homme et Société. 2017. dumas-02368575 HAL Id: dumas-02368575 https://dumas.ccsd.cnrs.fr/dumas-02368575 Submitted on 18 Nov 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial - NoDerivatives| 4.0 International License UNIVERSITÉ RENNES 2 Master Recherche ELECTRA – CELLAM Lost in serial television authorship : L'équipe des scénaristes de Lost comme un auteur pluriel ou quelques propositions méthodologiques pour analyser l'auctorialité des séries télévisées Mémoire de Recherche Discipline : Littératures comparées Présenté et soutenu par Quentin FISCHER en septembre 2017 Directeurs de recherche : Jean Cléder et Charline Pluvinet 1 « Créer une série, c'est d'abord imaginer son histoire, se réunir avec des auteurs, la coucher sur le papier. Puis accepter de lâcher prise, de la laisser vivre une deuxième vie. -

The Men of the “New” Makushin Village, Like Practically All Able-Bodied

Chapter 6 The Lives of Sea Otter Hunters he men of the “new” Makushin Village, like practically all able-bodied Unanga{ men, were active sea otter hunters employed by the AC T Company. The reports that document the beginning of the long and irreversible decline of sea otter hunting tell us little about individuals. Among the names that do surface occasionally is that of Lazar Gordieff. He appears six times in the 1885-1889 AC Company copybook and in a few other documents. These fragmented records provide little more than shadows, but they are far more than we have for most Unanga{ of the late 19th century. Lazar was twenty-two in 1878 and living with his widowed father, two brothers and a sister at Chernofski.1 In a June 1885 letter from Rudolph Neumann, since 1880 the AC Company general agent at Unalaska, we learn that Lazar was given dried seal throats.2 From this it can be deduced that he crafted delicate models of kayaks. The throats of fur seals, removed, cleaned, and dried during the seal harvests in the Pribilof Islands, were the preferred material for covering the intricate wooden frames. This letter went to the agent on Wosnesenski Island, in the heart of the eastern sea otter grounds, where Gordieff was part of the summer hunting party. He may have spent time between hunts carving and assembling models. A few of these trade items, all anonymous, survive in museums and testify to intimate knowledge of the kayak and to a high degree of craftsmanship. The hunters were still away in August, but after they had returned to Unalaska in October and Neumann had gone over the records, which arrived on a subsequent ship, he discovered that Lazar owed the company $166 while another man owed $805. -

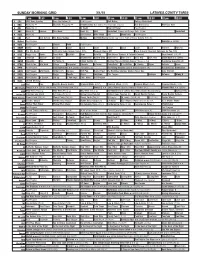

Sunday Morning Grid 4/12/15 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 4/12/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Bull Riding Remembers 2015 Masters Tournament Final Round. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News Paid Program Luna! Poppy Cat Tree Fu Figure Skating 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å Explore Incredible Dog Challenge 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program I Love Lucy I Love Lucy 13 MyNet Paid Program Red Lights ›› (2012) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Cosas Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local RescueBot RescueBot 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Cooking Chefs Life Simply Ming Lidia 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News TBA Things That Aren’t Here Anymore More Things Aren’t Here Anymore 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bucket-Dino Bucket-Dino Doki (TVY) Doki Ad Dive, Olly Dive, Olly E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial 34 KMEX Paid Program Al Punto (N) Fútbol Central (N) Fútbol Mexicano Primera División: Toluca vs Atlas República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Best Praise Super Kelinda Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Program Hocus Pocus ›› (1993) Bette Midler. -

June 29, 2020 17 Ill. Adm. Code Ch. I

SEPTEMBER 24, 2021 17 ILL. ADM. CODE CH. I, SEC. 685 TITLE 17: CONSERVATION CHAPTER I: DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES SUBCHAPTER b: FISH AND WILDLIFE PART 685 YOUTH HUNTING SEASONS Section 685.10 Statewide Season for White-Tailed Deer Hunting 685.20 Statewide Deer Permit Requirements 685.30 Statewide Firearm Requirements for Hunting the Youth Deer Season 685.40 Statewide Deer Hunting Rules 685.50 Reporting Harvest of Deer 685.60 Rejection of Application/Revocation of Deer Permits 685.70 Regulations at Various Department-Owned or -Managed Sites 685.80 Youth White-Tailed Deer Hunt (Repealed) 685.90 Heritage Youth Wild Turkey Hunt – Spring Season (Repealed) 685.100 Youth Pheasant Hunting (Repealed) 685.110 Youth Waterfowl Hunting 685.120 Youth Dove Hunting (Repealed) AUTHORITY: Implementing and authorized by Sections 1.3, 1.4, 2.24, 2.25, 2.26 and 3.36 of the Wildlife Code [520 ILCS 5]. SOURCE: Adopted at 20 Ill. Reg. 12452, effective August 30, 1996; amended at 21 Ill. Reg. 14548, effective October 24, 1997; amended at 25 Ill. Reg. 6904, effective May 21, 2001; amended at 26 Ill. Reg. 4418, effective March 11, 2002; amended at 26 Ill. Reg. 13828, effective September 5, 2002; amended at 27 Ill. Reg. 14332, effective August 25, 2003; amended at 29 Ill. Reg. 20469, effective December 2, 2005; amended at 30 Ill. Reg. 12222, effective June 28, 2006; emergency amendment at 31 Ill. Reg. 12096, effective August 1, 2007, for a maximum of 150 days; amended at 31 Ill. Reg. 14829, effective October 18, 2007; amended at 32 Ill. -

The Expression of Orientations in Time and Space With

The Expression of Orientations in Time and Space with Flashbacks and Flash-forwards in the Series "Lost" Promotor: Auteur: Prof. Dr. S. Slembrouck Olga Berendeeva Master in de Taal- en Letterkunde Afstudeerrichting: Master Engels Academiejaar 2008-2009 2e examenperiode For My Parents Who are so far But always so close to me Мои родителям, Которые так далеко, Но всегда рядом ii Acknowledgments First of all, I would like to thank Professor Dr. Stefaan Slembrouck for his interest in my work. I am grateful for all the encouragement, help and ideas he gave me throughout the writing. He was the one who helped me to figure out the subject of my work which I am especially thankful for as it has been such a pleasure working on it! Secondly, I want to thank my boyfriend Patrick who shared enthusiasm for my subject, inspired me, and always encouraged me to keep up even when my mood was down. Also my friend Sarah who gave me a feedback on my thesis was a very big help and I am grateful. A special thank you goes to my parents who always believed in me and supported me. Thanks to all the teachers and professors who provided me with the necessary baggage of knowledge which I will now proudly carry through life. iii Foreword In my previous research paper I wrote about film discourse, thus, this time I wanted to continue with it but have something new, some kind of challenge which would interest me. After a conversation with my thesis guide, Professor Slembrouck, we decided to stick on to film discourse but to expand it. -

Canadian Journal of Environmental Education, 18, 2013 Hunting for Ecological Learning

Hunting for Ecological Learning Joel B. Pontius, University of Wyoming, USA; David A. Greenwood, Lakehead University, Canada; Jessica L. Ryan, Laramie, Wyoming, USA; Eli A. Greenwood, Thunder Bay, Canada Abstract Considering (a) the many potential connections between hunting, culture, and environmental thought, (b) how much hunters have contributed to the conservation movement and to the protection of a viable land base, and (c) renewed interest in hunting as part of the wider movement toward eating local, non-industrialized food, we seek to bring hunting out of the margins and into a more visible role as a legitimate focus for environmental learning. To dig beneath the sometimes dismissive stereotypes that often marginalize hunters and hunting, and to explore hunting as a practice of ecological learning, we went straight to the source— we went hunting. Through narrative inquiry, this paper explores the ecological learning experienced in the context of a weeklong pronghorn antelope hunt in traditional Cheyenne and Arapahoe hunting territory in central Wyoming. By juxtaposing four voices, we recreate the hunting cycle and make meaning of our experience learning about ourselves, our environment, our food, and the more- than-human world. Résumé Compte tenu, a) des nombreux liens potentiels entre la chasse, la culture et la pensée environnementale, b) de la contribution considérable des chasseurs au mouvement environnemental et à la protection d’un habitat naturel durable, et c) du regain d’intérêt pour la chasse au sein du mouvement pour la production alimentaire locale et non industrielle, nous cherchons à sortir la chasse de la marginalité et d’en accroître la visibilité dans le but légitime de l’apprentissage environnemental. -

Sunday Morning Grid 3/1/15 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 3/1/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program Bull Riding College Basketball 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å Snowboarding U.S. Grand Prix: Slopestyle. (Taped) Red Bull Series PGA Tour Golf 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Explore This Week News (N) NBA Basketball Clippers at Chicago Bulls. (N) Å Basketball 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday NASCAR Racing Sprint Cup Series: Folds of Honor QuikTrip 500. (N) 13 MyNet Paid Program Swimfan › (2002) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR T’ai Chi, Health JJ Virgin’s Sugar Impact Secret (TVG) Deepak Chopra MD Suze Orman’s Financial Solutions for You (TVG) 28 KCET Raggs New. Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Rick Steves’ Europe: A Cultural Carnival Over Hawai’i (TVG) Å 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bucket-Dino Bucket-Dino Doki (TVY7) Doki (TVY7) Dive, Olly Dive, Olly Uncle Buck ›› (1989) 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Al Punto (N) Fútbol Central (N) Mexico Primera Division Soccer: Toluca vs Azul República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. -

NEW RESUME Current-9(5)

DEEDEE BRADLEY CASTING DIRECTOR [email protected] 818-980-9803 X2 TELEVISION PILOTS * Denotes picked up for series SWITCHED AT BIRTH* One hour pilot for ABC Family 2010 Executive Producers: Lizzy Weiss, Paul Stupin Director: Steve Miner BEING HUMAN* One hour pilot for Muse Ent./SyFy 2010 Executive Producers: Jeremy Carver, Anna Fricke, Michael Prupas Director: Adam Kane UNTITLED JUSTIN ADLER PILOT Half hour pilot for Sony/NBC 2009 Executive Producers: Eric Tannenbaum, Kim Tannenbaum, Mitch Hurwitz, Joe Russo, Anthony Russo, Justin Adler, David Guarascio, Moses Port Directors: Joe Russo and Anthony Russo PARTY DOWN * Half hour pilot for STARZ Network 2008 Executive Producers: Rob Thomas, Paul Rudd Director: Rob Thomas BEVERLY HILLS 90210* One hour pilot for CBS/Paramount and CW Network. Executive Producers: Gabe Sachs, Jeff Judah, Mark Piznarski, Rob Thomas Director: Mark Piznarski MERCY REEF aka AQUAMAN One hour pilot for Warner Bros./CW 2006 Executive Producers: Miles Millar, Al Gough, Greg Beeman Director : Greg Beeman Shared casting..Joanne Koehler VERONICA MARS* One hour pilot for Stu Segall Productions/UPN 2004 Executive Producers: Joel Silver, Rob Thomas Director: Mark Piznarski SAVING JASON Half hour pilot for Warner Bros./WBN 2003 Executive Producer: Winifred Hervey Director: Stan Lathan NEWTON One hour pilot for Warner Bros/UPN 2003 Executive Producers: Joel Silver, Gregory Noveck, Craig Silverstein Director: Lesli Linka Glatter ROCK ME BABY* Half hour pilot for Warner Bros./UPN 2003 Executive Producers: Tony Krantz, Tim Kelleher -

Superior Court Decision

IN THE SUPERIOR COURT FOR THE STATE OF ALASKA THIRD JUDICIAL DISTRICT AT ANCHORAGE ) ERIC SA LIT AN, ) ) Appellant, ) v. ) ) ALASKA BIG GAME ) COMMERCIAL SERVICES BOARD, ) ) Appellee. ) ~~~~~~~~~.) Case No. 3AN-l 6-07948CI ORDER UPON DE NOVO REVIEW ISSUE/BACKGROUND The Alaska Division of Corporations, Business, and Professional Licensing filed an Accusation li sting a number of counts against hunting guide Eric Salitan arising out of an August, 2012 sheep hunt in the Brooks Range. The Accusation proceeded to a three- day evidentiary hearing before an administrative law judge. Mr. Salitan participated in the hearing and made no objection to the procedure afforded to him during this hearing. Following this hearing, the ALJ drafted proposed findings of fact and a proposed decision, which was addressed by the Big Game Commercial Services Board. (The Board) Two members of the Board disclosed that they had conflicts and would refrain from voting on whether or not to accept the proposed findings of fact and decision. Despite this disclosure, both members participated in discussing the matter and voting on it. One of the members participated in an executive session where the Salitan order was Salita11 v. Big Game Commercial Services Board. 3AN-l 6-07948CJ Page l of 7 discussed. Ultimately an amended order was signed by the board finding that Mr. Salitan had violated the contract he had with his clients and imposing sanctions and reprimands. Mr. Salitan appealed, objecting to the Board's procedures, and thus the Board's findings. After considering Mr. Salitan's appeal from the Big Game Commercial Services Board's decision imposing discipline on Mr. -

Before the Alaska Office of Administrative Hearings on Referral from the Big Game Commercial Services Board

BEFORE THE ALASKA OFFICE OF ADMINISTRATIVE HEARINGS ON REFERRAL FROM THE BIG GAME COMMERCIAL SERVICES BOARD In the Matter of ) ) ERIK R. SALITAN ) OAH No. 15-1346-GUI ) Agency No. 2014-000912 CORRECTED DECISION AFTER REMAND I. Introduction Erik Salitan is a licensed registered guide-outfitter, a level of guiding license he achieved in 2008 after working several years as an assistant guide. At 32 years old, he is one of the youngest, if not the youngest, registered guides in the state. His main residence is in No Name, Alaska, a small community in the southern Brooks Range. He offers guided hunts in the Brooks Range and in other areas of Alaska. His guiding business is named “Bushwack Alaska Guiding and Outfitting.”1 This case concerns three different incidents involving Mr. Salitan. The first occurred during a 2012 sheep hunt, when, due to bad weather, two clients remained in a remote camp much longer than expected. The second occurred in early 2014 at two hunting trade shows in the Lower 48, when Mr. Salitan advertised and booked hunts even though his license was expired. The third occurred during a 2014 sheep hunt, when Mr. Salitan’s hunting party used a remote landing strip that was occupied by a different guide’s hunting camp. Based on these three separate incidents, the Division of Corporations, Business and Professional Licensing filed a six-count accusation against Mr. Salitan. One of the counts was dismissed before the hearing. A three-day hearing on the remaining five-count accusation was held in Juneau on March 23-25, 2016. -

College in 1967. the Purposes Were to Provide the Trainees

OCLOIENT SES1112 ED 032 552 cc 004 229 ay-Ayers. George E.. Ed Rehabilitating the Culturally Disadvantageil. Rehabilitation Services Administration (DHEW). Washington. D.C. Pub Date 16 Aug 67 Note-140p_; Report of a Regional Conferenceon Rehabilitating the Culturally Disadvantaged held at Mankato State College. Mankato. Minnesota. August 16-18. 1967 EDRS Price MF -S0.75 HC -S7.10 Descriptors- Culturaily Disadvantaged. Disadvantaged Environment. DisadvantagedYouth. Indians. Program Descriptions. Rehabilitation. Rehabilitation Programs. Vocational Rehabilitation A conference on rehabilitating the culturally disadvantagedwas held at Mankato College in 1967. The purposeswere to provide the trainees (1) the essential information relative to the characteriQtics and problems of.as well as the methods for. rehabilitating the culturally deprived; (2)an opportunity to cooperatively develop criteria for utilization by state vocational rehabilitation agencies in diagnosing cultural deprivation; and (3) an opportunity to delineate and develop procedures for increasingtheprovision of vocationrehabilitationservicestotheculturally disadvantaged. The four sections of the report deal with the followingareas: (1) rehabilitating the culturally deprived. (2) approachesto rehabilitating the culturally deprived. (3) representative rehabilitationprograms for the culturally disadvantaged. and (4) summary reports of workshop sessions. Topics discussedinclude: (1) preparingdiagnosticiansforworkingwiththeculturallydisadvantaged.(2) communicating with the culturally -

The Casting Director Guide from Now Casting, Inc

The Casting Director Guide From Now Casting, Inc. This printable Casting Director Guide includes CD listings exported from the CD Connection in NowCasting.com’s Contacts NOW area. The Guide is an easy way to get familiar with all the CD’s. Or, you might want to print a copy that lives in your car. Keep in mind that the printable CD Guide is created approximately once a month while the CD Connection is updated constantly. There will be info in the printable “Guide” that is out of date almost immediately… that’s the nature of casting. If you need a more comprehensive, timely and searchable research and marketing tool then you should consider using Contacts NOW in NowCasting.com. In Contacts NOW, you can search the CD database directly, make personal notes, create mailing lists, search Agents, make your own Custom Contacts and print labels. You can even export lists into Postcards NOW – a service that lets you create and mail postcards all from your desktop! You will find Contacts NOW in your main NowCasting menu under Get it NOW or Guides and Labels. Questions? Contact the NowCasting Staff @ 818-841-7165 Now Casting.com We’re Back! Many post hiatus updates! October ‘09 $13.00 Casting Director Guide Run BY Actors FOR Actors More UP- TO-THE-MINUTE information than ANY OTHER GUIDE Compare to the others with over 100 pages of information Got Casting Notices? We do! www.nowcasting.com WHY BUY THIS BOOK? Okay, there are other books on the market, so why should you buy this one? Simple.