Contemporary Institutional and Popular Frameworks for Gender Variance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Attraction and Sex Symbol of Males in the Eyes of Malaysian Male-To-Female Transsexuals

International Journal of Social Science and Humanity, Vol. 3, No. 2, March 2013 Attraction and Sex Symbol of Males in the Eyes of Malaysian Male-to-Female Transsexuals Amran Hassan and Suriati Ghazali they are female in emotion but „trapped‟ in the male bodies. Abstract—Male-to-female transsexual issues, especially their sexual orientation, has become complicated due to their tendency to regard themselves as women, and are exclusively II. REVIEW OF LITERATURE attracted to men. This paper explores one group in male-to-female transsexuals, which is homosexual transsexuals, Research on male-to-female transsexuals‟ sexual attraction and their attraction towards homosexual and heterosexual men. towards men is still scarce. One among a few is by [7], who The objective of this paper is to identify aspects of sexual discovered that attraction to Male Physique was positively attraction in the body or nature of the men that attract correlated with Sexual Attraction to Males among homosexual transsexuals to develop romantic relationship with Autogynephilic transsexuals. It is possible that attraction to them. Qualitative methods were used in gathering the data. This includes in-depth interviews that have been carried out on six the male physique could develop along with the secondary homosexual transsexuals, which were selected using purposive emergence of attraction to males that [5] describes. and snowball sampling. The location of the fieldwork was Port Transsexual research in Malaysia generally focuses on Dickson, Negeri Sembilan, Malaysia. The result shows that factors leading to transsexualism and issues around it, rather facial appearance, specific body parts such as chest, calves and than sexuality and sexual attraction. -

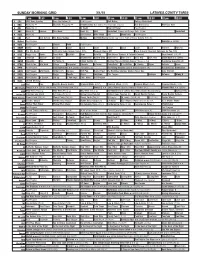

Sunday Morning Grid 4/12/15 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 4/12/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Bull Riding Remembers 2015 Masters Tournament Final Round. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News Paid Program Luna! Poppy Cat Tree Fu Figure Skating 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å Explore Incredible Dog Challenge 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program I Love Lucy I Love Lucy 13 MyNet Paid Program Red Lights ›› (2012) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Cosas Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local RescueBot RescueBot 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Cooking Chefs Life Simply Ming Lidia 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News TBA Things That Aren’t Here Anymore More Things Aren’t Here Anymore 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bucket-Dino Bucket-Dino Doki (TVY) Doki Ad Dive, Olly Dive, Olly E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial 34 KMEX Paid Program Al Punto (N) Fútbol Central (N) Fútbol Mexicano Primera División: Toluca vs Atlas República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Best Praise Super Kelinda Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Program Hocus Pocus ›› (1993) Bette Midler. -

The Reconstruction of Gender and Sexuality in a Drag Show*

DUCT TAPE, EYELINER, AND HIGH HEELS: THE RECONSTRUCTION OF GENDER AND SEXUALITY IN A DRAG SHOW* Rebecca Hanson University of Montevallo Montevallo, Alabama Abstract. “Gender blending” is found on every continent; the Hijras in India, the female husbands in Navajo society, and the travestis in Brazil exemplify so-called “third genders.” The American version of a third gender may be drag queen performers, who confound, confuse, and directly challenge commonly held notions about the stability and concrete nature of both gender and sexuality. Drag queens suggest that specific gender performances are illusions that require time and effort to produce. While it is easy to dismiss drag shows as farcical entertainment, what is conveyed through comedic expression is often political, may be used as social critique, and can be indicative of social values. Drag shows present a protest against commonly held beliefs about the natural, binary nature of gender and sexuality systems, and they challenge compulsive heterosexuality. This paper presents the results of my observational study of drag queens. In it, I describe a “routine” drag show performance and some of the interactions and scripts that occur between the performers and audience members. I propose that drag performers make dichotomous American conceptions of sexuality and gender problematical, and they redefine homosexuality and transgenderism for at least some audience members. * I would like to thank Dr. Stephen Parker for all of his support during the writing of this paper. Without his advice and mentoring I could never have started or finished this research. “Gender blending” is found on every continent. The Hijras in India, the female husbands in Navajo society, and the travestis in Brazil are just a few examples of peoples and practices that have been the subjects for “third gender” studies. -

Transgender Health at the Crossroads: Legal Norms, Insurance Markets, and the Threat of Healthcare Reform

Yale Journal of Health Policy, Law, and Ethics Volume 11 Issue 2 Yale Journal of Health Policy, Law, and Article 4 Ethics 2011 Transgender Health at the Crossroads: Legal Norms, Insurance Markets, and the Threat of Healthcare Reform Liza Khan Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.yale.edu/yjhple Part of the Health Law and Policy Commons, and the Legal Ethics and Professional Responsibility Commons Recommended Citation Liza Khan, Transgender Health at the Crossroads: Legal Norms, Insurance Markets, and the Threat of Healthcare Reform, 11 YALE J. HEALTH POL'Y L. & ETHICS (2011). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.yale.edu/yjhple/vol11/iss2/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Yale Law School Legal Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Yale Journal of Health Policy, Law, and Ethics by an authorized editor of Yale Law School Legal Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Khan: Transgender Health at the Crossroads NOTE Transgender Health at the Crossroads: Legal Norms, Insurance Markets, and the Threat of Healthcare Reform Liza Khan INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................... 376 I. MEDICALIZED IDENTITY ...................................................................... 379 A. TRANSGENDER HEALTHCARE ..................................... 380 B. TRANSGENDER LAW AND MEDICINE: INTERSECTION OR DISCONNECT?.. 382 C. NEGOTIATING THE MEDICAL CONSTRUCTION OF GENDER: -

Early History of the Concept of Autogynephilia

Archives of Sexual Behavior, Vol. 34, No. 4, August 2005, pp. 439–446 (C 2005) DOI: 10.1007/s10508-005-4343-8 Early History of the Concept of Autogynephilia Ray Blanchard, Ph.D.1,2,3 Received August 4, 2004; revision received November 27, 2004; accepted November 27, 2004 Since the beginning of the last century, clinical observers have described the propensity of certain males to be erotically aroused by the thought or image of themselves as women. Because there was no specific term to denote this phenomenon, clinicians’ references to it were generally oblique or periphrastic. The closest available word was transvestism. The definition of transvestism accepted by the end of the twentieth century, however, did not just fail to capture the wide range of erotically arousing cross-gender behaviors and fantasies in which women’s garments per se play a small role or none at all; it actually directed attention away from them. The absence of an adequate terminology became acute in the writer’s research on the taxonomy of gender identity disorders in biological males. This had suggested that heterosexual, asexual, and bisexual transsexuals are more similar to each other—and to transvestites—than any of them is to the homosexual type, and that the common feature in transvestites and the three types of non-homosexual transsexuals is a history of erotic arousal in association with the thought or image of themselves as women. At the same time, the writer was becoming aware of male patients who are sexually aroused only by the idea of having a woman’s body and not at all by the idea of wearing women’s clothes. -

The Evolution & Politics of First-Wave Queer Activism

“Glory of Yet Another Kind”: The Evolution & Politics of First-Wave Queer Activism, 1867-1924 GVGK Tang HIST4997: Honors Thesis Seminar Spring 2016 1 “What could you boast about except that you stifled my words, drowned out my voice . But I may enjoy the glory of yet another kind. I raised my voice in free and open protest against a thousand years of injustice.” —Karl Heinrich Ulrichs after being shouted down for protesting anti-sodomy laws in Munich, 18671 Queer* history evokes the familiar American narrative of the Stonewall Uprising and gay liberation. Most people know that lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people rose up, like other oppressed minorities in the sixties, with a never-before-seen outpouring of social activism, marches, and protests. Popular historical discourse has led the American public to believe that, before this point, queers were isolated, fractured, and impotent – relegated to the shadows. The postwar era typically is conceived of as the critical turning point during which queerness emerged in public dialogue. This account of queer history depends on a social category only recently invented and invested with political significance. However, Stonewall was not queer history’s first political milestone. Indeed, the modern LGBT movement is just the latest in a series of campaign periods that have spanned a century and a half. Queer activism dawned with a new lineage of sexual identifiers and an era of sexological exploration in the mid-nineteenth century. German lawyer Karl Heinrich Ulrichs was first to devise a politicized queer identity founded upon sexological theorization.2 He brought this protest into the public sphere the day he outed himself to the five hundred-member Association 1 Karl Heinrich Ulrichs, The Riddle of "Man-Manly" Love, trans. -

A Look at 'Fishy Drag' and Androgynous Fashion: Exploring the Border

This is a repository copy of A look at ‘fishy drag’ and androgynous fashion: Exploring the border spaces beyond gender-normative deviance for the straight, cisgendered woman. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/121041/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Willson, JM orcid.org/0000-0002-1988-1683 and McCartney, N (2017) A look at ‘fishy drag’ and androgynous fashion: Exploring the border spaces beyond gender-normative deviance for the straight, cisgendered woman. Critical Studies in Fashion and Beauty, 8 (1). pp. 99-122. ISSN 2040-4417 https://doi.org/10.1386/csfb.8.1.99_1 (c) 2017, Intellect Ltd. This is an author produced version of a paper published in Critical Studies in Fashion and Beauty. Uploaded in accordance with the publisher's self-archiving policy. Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ 1 JACKI WILLSON University of Leeds NICOLA McCARTNEY University of the Arts, London and University of London A look at ‘fishy drag’ and androgynous fashion: Exploring the border spaces beyond gender-normative deviance for the straight, cisgendered woman Abstract This article seeks to re-explore and critique the current trend of androgyny in fashion and popular culture and the potential it may hold for gender deviant dress and politics. -

On the Just and Accurate Representation of Transgender Persons in Research and the Clinic

Portland State University PDXScholar Community Health Faculty Publications and Presentations School of Community Health 3-2014 On the Just and Accurate Representation of Transgender Persons in Research and the Clinic Alexis Dinno Portland State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/commhealth_fac Part of the Community Health Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Citation Details Dinno, Alexis, "On the Just and Accurate Representation of Transgender Persons in Research and the Clinic" (2014). Community Health Faculty Publications and Presentations. 40. https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/commhealth_fac/40 This Presentation is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Community Health Faculty Publications and Presentations by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. ON THE JUST & ACCURATE REPRESENTATION OF TRANSGENDER PERSONS IN RESEARCH & THE CLINIC March 27, 2014 ALEXIS DINNO, SCD, MPM, MEM built on a collaboration with Molly C. Franks Jenn Burleton Tyler C. Smith About me and why I am here… Transgender Transsexual Drag performer Epidemiologist Social justice activist My collaborators are likewise: sexual and gender minorities public health professionals motivated by social justice We desire just representation of transgender persons. Photograph of Alexis Dinno http://ww4.hdnux.com/photos/10/30/12/2196119/5/628x471.jpg by Lea Suzuki of the SF Chronicle, © 2002 Aside: basics of epidemiology Epidemiology is the study of health and disease in populations with the aim of improving health in those populations. -

Uranianism by Ruth M

Uranianism by Ruth M. Pettis Encyclopedia Copyright © 2015, glbtq, Inc. Entry Copyright © 2004, glbtq, inc. Reprinted from http://www.glbtq.com "Uranian" and "Uranianism" were early terms denoting homosexuality. They were in English use primarily from the 1890s through the first quarter of the 1900s and applied to concurrent and overlapping trends in sexology, social philosophy, and poetry, particularly in Britain. "Uranian" was a British derivation from "Urning," a word invented by German jurist Karl Heinrich Ulrichs in the 1860s. In a series of pamphlets Ulrichs proposed a scheme for classifying the varieties of sexual orientation, assuming their occurrence in natural science. He recognized three principal categories among males: "Dionings" (heterosexuals), "Urnings" (homosexuals), and "Uranodionings" (bisexuals), based on their preferences for sexual partners. (A fourth category, hermaphrodites, he acknowledged but dismissed as occurring too infrequently to be significant.) Ulrichs further subdivided Urnings into those who prefer effeminate males, masculine males, adolescent males, and a fourth category who repressed their natural yearnings and lived heterosexually. Those who applied Ulrichs' system felt the need for Top: Edward Carpenter. analogous terms for women, and devised the terms "Urningins" (lesbians) and Center: John Addington "Dioningins" (heterosexual women). Symonds. Above: Walt Whitman. Images courtesy Library The term "Uranian" also alludes to the discussion in Plato's Symposium of the of Congress Prints and "heavenly" form of love (associated with Aphrodite as the daughter of Uranus) Photographs Division. practiced by those who "turn to the male, and delight in him who is the more valiant and intelligent nature." This type of love was distinguished from the "common" form of love associated with heterosexual love of women. -

Trans-Phobia and the Relational Production of Gender Elaine Craig

Hastings Women’s Law Journal Volume 18 Article 2 Number 2 Summer 2007 1-1-2007 Trans-Phobia and the Relational Production of Gender Elaine Craig Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hwlj Part of the Law and Gender Commons Recommended Citation Elaine Craig, Trans-Phobia and the Relational Production of Gender, 18 Hastings Women's L.J. 137 (2007). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hwlj/vol18/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Women’s Law Journal by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Trans-Phobia and the Relational Production of Gender Elaine Craig* In 1431, Joan of Arc, a nineteen-year-old cross-dresser, was burned alive at the stake because she refused to stop dressing in men's clothing.' Nearly six centuries later, in 2002, Gwen Araujo, a seventeen-year-old male-to-female transsexual, was strangled to death by two men who later claimed what can be described as a "trans panic defense" because they hadn't realized that Gwen was biologically male before they had sex with her.2 Individuals who transgress gender norms are among the most despised, marginalized, and discriminated against members of many societies. 3 A deep seated fear of transgender individuals reveals itself in a plethora of contexts and across a wide spectrum of demographics. Perhaps most disturbingly, intolerance towards and discrimination against transgender individuals is found not only among the ranks of those whose gender offers them opportunity and privilege, but also among those whose own gender identity and expression has been a source of oppression and persecution. -

Media Reference Guide

media reference guide NINTH EDITION | AUGUST 2014 GLAAD MEDIA REFERENCE GUIDE / 1 GLAAD MEDIA CONTACTS National & Local News Media Sports Media [email protected] [email protected] Entertainment Media Religious Media [email protected] [email protected] Spanish-Language Media GLAAD Spokesperson Inquiries [email protected] [email protected] Transgender Media [email protected] glaad.org/mrg 2 / GLAAD MEDIA REFERENCE GUIDE TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION FAIR, ACCURATE & INCLUSIVE 4 GLOSSARY OF TERMS / LANGUAGE LESBIAN / GAY / BISEXUAL 5 TERMS TO AVOID 9 TRANSGENDER 12 AP & NEW YORK TIMES STYLE 21 IN FOCUS COVERING THE BISEXUAL COMMUNITY 25 COVERING THE TRANSGENDER COMMUNITY 27 MARRIAGE 32 LGBT PARENTING 36 RELIGION & FAITH 40 HATE CRIMES 42 COVERING CRIMES WHEN THE ACCUSED IS LGBT 45 HIV, AIDS & THE LGBT COMMUNITY 47 “EX-GAYS” & “CONVERSION THERAPY” 46 LGBT PEOPLE IN SPORTS 51 DIRECTORY OF COMMUNITY RESOURCES 54 GLAAD MEDIA REFERENCE GUIDE / 3 INTRODUCTION Fair, Accurate & Inclusive Fair, accurate and inclusive news media coverage has played an important role in expanding public awareness and understanding of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) lives. However, many reporters, editors and producers continue to face challenges covering these issues in a complex, often rhetorically charged, climate. Media coverage of LGBT people has become increasingly multi-dimensional, reflecting both the diversity of our community and the growing visibility of our families and our relationships. As a result, reporting that remains mired in simplistic, predictable “pro-gay”/”anti-gay” dualisms does a disservice to readers seeking information on the diversity of opinion and experience within our community. Misinformation and misconceptions about our lives can be corrected when journalists diligently research the facts and expose the myths (such as pernicious claims that gay people are more likely to sexually abuse children) that often are used against us. -

Sunday Morning Grid 3/1/15 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 3/1/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program Bull Riding College Basketball 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å Snowboarding U.S. Grand Prix: Slopestyle. (Taped) Red Bull Series PGA Tour Golf 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Explore This Week News (N) NBA Basketball Clippers at Chicago Bulls. (N) Å Basketball 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday NASCAR Racing Sprint Cup Series: Folds of Honor QuikTrip 500. (N) 13 MyNet Paid Program Swimfan › (2002) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR T’ai Chi, Health JJ Virgin’s Sugar Impact Secret (TVG) Deepak Chopra MD Suze Orman’s Financial Solutions for You (TVG) 28 KCET Raggs New. Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Rick Steves’ Europe: A Cultural Carnival Over Hawai’i (TVG) Å 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bucket-Dino Bucket-Dino Doki (TVY7) Doki (TVY7) Dive, Olly Dive, Olly Uncle Buck ›› (1989) 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Al Punto (N) Fútbol Central (N) Mexico Primera Division Soccer: Toluca vs Azul República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B.