History in Songs and Songs in History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Irish Cultural Center of Cincinnati to Hold Green Tie Affair

Irish Cultural Center November 2013 of Cincinnati to Hold ianohio.com Green Tie Affair Saturday, November 2nd Saw Doctors Leo and Anto Hit the Road … page 2 Irish Cultural Center of Cincinnati Celebrates 4th Anniversary . page 6 Rattle of a Thompson Gun … page 7 Opportunity Ireland . page 9 Home to Mayo. pages 13 - 16 Big Screen to Broadway: Once Comes to Cleveland . page 19 Cover artwork by Cindy Matyi http://matyiart.com 2 IAN Ohio “We’ve Always Been Green!” www.ianohio.com November 2013 Saw Doctors Solo, Leo and Anto Hit the Road a little place back in Ireland where we together quite quickly. So we wanted it tested it out, and got a good response. to be different from anything we’d re- By Pete Roche, Special to the OhIAN of their stepping off the plane, and the And it looks like it worked. But we’ll be corded before. So we used the mandolin, guitarist sounded enthusiastic about tweaking it as we figure it out! which is a very different thing than what The North Coast’s music-loving Irish winding his way through the Midwest OhIAN: Apart from the music, how we’d done before with the Saw Doctors. contingent always turns out in strong in true troubadour fashion. will this tour be different from a Saw And I think that’s important. People are numbers whenever the rock quintet OhIAN: Hello again, Leo! Great to Doctors tour? saying to me it feels like they came to from the little Galway town of Tuam be catching up with you again! So you LEO: It’s going to be a whole new Ireland before we left it, because they’d play our neck of the woods. -

Identity, Authority and Myth-Making: Politically-Motivated Prisoners and the Use of Music During the Northern Irish Conflict, 1962 - 2000

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Queen Mary Research Online Identity, authority and myth-making: Politically-motivated prisoners and the use of music during the Northern Irish conflict, 1962 - 2000 Claire Alexandra Green Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy 1 I, Claire Alexandra Green, confirm that the research included within this thesis is my own work or that where it has been carried out in collaboration with, or supported by others, that this is duly acknowledged below and my contribution indicated. Previously published material is also acknowledged below. I attest that I have exercised reasonable care to ensure that the work is original, and does not to the best of my knowledge break any UK law, infringe any third party’s copyright or other Intellectual Property Right, or contain any confidential material. I accept that the College has the right to use plagiarism detection software to check the electronic version of the thesis. I confirm that this thesis has not been previously submitted for the award of a degree by this or any other university. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author. Signature: Date: 29/04/19 Details of collaboration and publications: ‘It’s All Over: Romantic Relationships, Endurance and Loyalty in the Songs of Northern Irish Politically-Motivated Prisoners’, Estudios Irlandeses, 14, 70-82. 2 Abstract. In this study I examine the use of music by and in relation to politically-motivated prisoners in Northern Ireland, from the mid-1960s until 2000. -

De Búrca Rare Books

De Búrca Rare Books A selection of fine, rare and important books and manuscripts Catalogue 141 Spring 2020 DE BÚRCA RARE BOOKS Cloonagashel, 27 Priory Drive, Blackrock, County Dublin. 01 288 2159 01 288 6960 CATALOGUE 141 Spring 2020 PLEASE NOTE 1. Please order by item number: Pennant is the code word for this catalogue which means: “Please forward from Catalogue 141: item/s ...”. 2. Payment strictly on receipt of books. 3. You may return any item found unsatisfactory, within seven days. 4. All items are in good condition, octavo, and cloth bound, unless otherwise stated. 5. Prices are net and in Euro. Other currencies are accepted. 6. Postage, insurance and packaging are extra. 7. All enquiries/orders will be answered. 8. We are open to visitors, preferably by appointment. 9. Our hours of business are: Mon. to Fri. 9 a.m.-5.30 p.m., Sat. 10 a.m.- 1 p.m. 10. As we are Specialists in Fine Books, Manuscripts and Maps relating to Ireland, we are always interested in acquiring same, and pay the best prices. 11. We accept: Visa and Mastercard. There is an administration charge of 2.5% on all credit cards. 12. All books etc. remain our property until paid for. 13. Text and images copyright © De Burca Rare Books. 14. All correspondence to 27 Priory Drive, Blackrock, County Dublin. Telephone (01) 288 2159. International + 353 1 288 2159 (01) 288 6960. International + 353 1 288 6960 Fax (01) 283 4080. International + 353 1 283 4080 e-mail [email protected] web site www.deburcararebooks.com COVER ILLUSTRATIONS: Our front and rear cover is illustrated from the magnificent item 331, Pennant's The British Zoology. -

Sponsorship Opportunity: I Am Ireland Film For

the Irish Fellowship Club of Chicago presents A concert being presented at Old Saint Pat’s in Chicago for broadcast on PBS “There will be all manner of celebrations during next year’s centennial but it’s hard – almost impossible – to imagine any will be as moving, entertaining, enlightening or soaring as I AM IRELAND.” – rick kogan, the chicago tribune I AM IRELAND The History of Ireland’s Road to Freedom 1798 ~ 1916 “As told through songs of her people” TELLING THE STORY OF IRISH INDEPENDENCE AND CREATING A LEGACY THAT WILL LIVE FOR GENERATIONS TO COME he goal of the I AM IRELAND show is to record the story of Ireland’s road to freedom filmed before a live audience at Old St. TPatrick’s Church in Chicago over a three-day period in the Fall of 2019, for distribution through the PBS Television Network. We are seek- ing to raise $500,000 to cover the cost of this production while simulta- neously raising scholarship funds for the Irish Fellowship Educational and Cultural Foundation. This filming and recording will be carried out by the acclaimed HMS Media Group, who recently filmed for broadcast the highly rated Chicago Voices Concert, (2017) featuring Renée Fleming and more recently, Jesus Christ Superstar for PBS. The I AM IRELAND show will feature traditional Irish Tenor Paddy Homan, together with 35 musicians from The City Lights Orchestra, under the direction of Rich Daniels. Additionally, there will be three traditional Irish musicians, along with an All-Ireland traditional Irish step dancer. The ninety-minute show takes audiences on a journey through the songs and speeches of Ireland’s road to freedom between 1798 and 1916. -

Exploring the Musical Traditions of Co. Leitrim & Co. Fermanagh

Exploring the Musical Traditions of County Leitrim & County Fermanagh In May 2020 Irish Arts Foundation launched a pioneering research programme. It centred on specific regional playing styles and influences within Irish traditional music originating from rural communities around the border counties of: Leitrim in the Republic of Ireland and Fermanagh in Northern Ireland. Themes 1. Regional identity. 2. Local musical traditions in Co. Leitrim and Fermanagh. 3. The families and individuals who kept the music alive, and their legacy today. Regional Identity In the time of the horse and cart - the ‘candle to bed’ age - each village, town and county had its own tunes and dances; a musical accent and dialect. This was due to relative rural isolation. So despite the close proximity of Co. Leitrim and Fermanagh, distinct regional identities - musical, religious and political – formed. When talking about regional identity and style there will always be generalisations; tunes do not carry passports and music has never been constrained by borders. Despite this, we will look at what can be widely termed, a Leitrim and a Fermanagh musical tradition. County Leitrim Leitrim is in the province of Connacht and part of the Border Region. Its largest town is Carrick-on-Shannon with a population of 3,134. Although one of Ireland’s smallest counties, Leitrim has a distinct musical tradition of flute and fiddle music. We will look at some of the individuals and groups who have shaped the Leitrim style of traditional music. Leitrim Flute Music “Co. Leitrim has preserved a distinct musical identity and tradition based largely on the flute. -

“Am I Not of Those Who Reared / the Banner of Old Ireland High?” Triumphalism, Nationalism and Conflicted Identities in Francis Ledwidge’S War Poetry

Romp /1 “Am I not of those who reared / The banner of old Ireland high?” Triumphalism, nationalism and conflicted identities in Francis Ledwidge’s war poetry. Bachelor Thesis Charlotte Romp Supervisor: dr. R. H. van den Beuken 15 June 2017 Engelse Taal en Cultuur Radboud University Nijmegen Romp /2 Abstract This research will answer the question: in what ways does the poetry written by Francis Ledwidge in the wake of the Easter Rising reflect a changing stance on his role as an Irish soldier in the First World War? Guy Beiner’s notion of triumphalist memory of trauma will be employed in order to analyse this. Ledwidge’s status as a war poet will also be examined by applying Terry Phillips’ definition of war poetry. By remembering the Irish soldiers who decided to fight in the First World War, new light will be shed on a period in Irish history that has hitherto been subjected to national amnesia. This will lead to more complete and inclusive Irish identities. This thesis will argue that Ledwidge’s sentiments with regards to the war changed multiple times during the last year of his life. He is, arguably, an embodiment of the conflicting loyalties and tensions in Ireland at the time of the Easter Rising. Key words: Francis Ledwidge, Easter Rising, First World War, Ireland, Triumphalism, war poetry, loss, homesickness Romp /3 Table of contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 4 Chapter 1 History and Theory ................................................................................................... -

Scottish and Irish Elements of Appalachian Fiddle Music

Butler University Digital Commons @ Butler University Undergraduate Honors Thesis Collection Undergraduate Scholarship 3-1995 Scottish and Irish Elements of Appalachian Fiddle Music Matthew S. Emmick Butler University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/ugtheses Part of the Ethnomusicology Commons, and the Musicology Commons Recommended Citation Emmick, Matthew S., "Scottish and Irish Elements of Appalachian Fiddle Music" (1995). Undergraduate Honors Thesis Collection. 21. https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/ugtheses/21 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Scholarship at Digital Commons @ Butler University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Thesis Collection by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Butler University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BUTLER UNIVERSITY HONORS PROGRAM Honors Thesis Certification Matthew S. Emmick Applicant (Name as It Is to appear on dtplomo) Scottish and Irish Elements of Appalachian Fiddle M'-Isic Thesis title _ May, 1995 lnter'lded date of commencemenf _ Read and approved by: ' -4~, <~ /~.~~ Thesis adviser(s)/ /,J _ 3-,;13- [.> Date / / - ( /'--/----- --",,-..- Commltte~ ;'h~"'h=j.R C~.16b Honors t-,\- t'- ~/ Flrst~ ~ Date Second Reader Date Accepied and certified: JU).adr/tJ, _ 2111c<vt) Director DiJe For Honors Program use: Level of Honors conferred: University Magna Cum Laude Departmental Honors in Music and High Honors in Spanish Scottish and Irish Elements of Appalachian Fiddle Music A Thesis Presented to the Departmt!nt of Music Jordan College of Fine Arts and The Committee on Honors Butler University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation Honors Matthew S. Emmick March, 24, 1995 -l _ -- -"-".,---. -

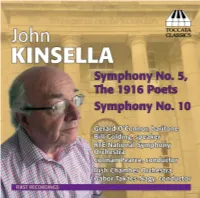

Toccata Classics TOCC0242 Notes

Americas, and from further aield: basically, if it’s good music and it hasn’t yet been recorded, JOHN KINSELLA, IRISH SYMPHONIST by Séamas da Barra John Kinsella was born in Dublin on 8 April 1932. His early studies at the Dublin College of Music were devoted to the viola as well as to harmony and counterpoint, but he is essentially self-taught as a composer. He started writing music as a teenager and although he initially adopted a straightforward, even conventional, tonal idiom, he began to take a serious interest in the compositional techniques of the European avant-garde from the early 1960s. He embraced serialism in particular as a liberating influence on his creative imagination, and he produced a substantial body of work during this period that quickly established him in Ireland as one of the most interesting younger figures of the day. In 1968 Kinsella was appointed Senior Assistant in the music department of Raidió Teilefís Éireann (RTÉ), the Irish national broadcasting authority, a position that allowed him to become widely acquainted with the latest developments in contemporary music, particularly through the International Rostrum of Composers organised under the auspices of UNESCO. But much of what he heard at these events began to strike him as dispiritingly similar in content, and he was increasingly persuaded that for many of his contemporaries conformity with current trends had become more P important than a desire to create out of inner conviction. As he found himself growing disillusioned with the avant-garde, his attitude to his own work began to change and he came to question the artistic validity of much of what he had written. -

Speech on Joseph Mary Plunkett, Delivered at Stonyhurst College Thursday, 29Th September, 2016

Speech on Joseph Mary Plunkett, delivered at Stonyhurst College Thursday, 29th September, 2016 As Ireland commemorates the centenary of the Easter Rising — the event that sparked a popular movement towards independence from the United Kingdom one hundred years ago this year — the tendency has been to focus, perhaps somewhat simplistically, on the history of the participants and of the event itself. But in the Easter Rising we find that history was born in literature, and reality in text. With the Celtic Revival in its latter days by 1916, and the rediscovery of national heroes from ancient myth, such as Cuchulain, permeating the popular imagination, it should not seem too surprising that a headmaster, a university professor, and an assortment of poets saw themselves — and became — the champions of Irish freedom. As the historian Standish O’Grady prophetically declared in the late nineteenth century: ‘We have now a literary movement, it is not very important; it will be followed by a political movement that will not be very important; then must come a military movement that will be important indeed.’1 The ideas crafted in the study took fire in the streets in 1916, and Joseph Mary Plunkett — poet, aesthete, military strategist, and rebel — offers a fascinating study of this nexus of thought and action. Plunkett is often mythologized as the hero who wed his sweetheart on the eve of his execution in May 1916, but I would like to broaden this narrative by framing this evening’s talk around not one but three women who profoundly shaped Plunkett’s life, and who are the subject of many poems he wrote, some of which I would like to share with you this evening. -

Fhfest Walk 2012

‘Dublin‘Dublin CanCan BeBe Heaven’Heaven’ TraditionalTraditional SingingSinging andand WalkingWalking TourTour SundaySunday 23rd23rd September,September, 11:00am,11:00am, TrinityTrinity CollegeCollege EnEntrance.trance. CollegeCollege GreenGreen Frank Harte Festival 2012 AN GÓILÍN - FRANK HARTE FESTIVAL Dublin Traditional Singing and Walking Tour Sunday 23rd September his year’s Frank Harte Festival walk will commence at the main entrance to Trinity College at College Green. TCD, the Alma Mater of Bram Stoker Twhose centenary is celebrated this year is appropriately the starting point for the walk as many of those featured in the walk were educated there including the lyricist Thomas Moore whose adjacent statue provides the second stop on the tour. This is the first of the many of the statues and memorials to famous Irish people and events which shaped the city’s and Ireland’s history that this years walk will visit. At each of the selected memorials a relevant tune, song or poem will be per- formed by Góilín regulars or festival guests maintaining Frank Harte’s belief that ‘those in power write the history and those who suffer write the songs’. The route this year will explore historic College Green then saunter up Grafton Street and its environs into St Stephens Green and continue along Merrion Row, turn into Merrion Street to Merrion Square to the last stop at the memorial to Oscar Wilde. The walkers are invited to then proceed to O’Donoghue’s of Merrion Row where the music and songs of the Dubliners will be fondly remembered. The theme of this year’s walk is Dublin Can Be Heaven better known as The Dublin Saunter – a song made famous by Dublin actor and entertainer Noel Purcell who was born in the Grafton Street vicinity. -

The Government's Executions Policy During the Irish Civil

THE GOVERNMENT’S EXECUTIONS POLICY DURING THE IRISH CIVIL WAR 1922 – 1923 by Breen Timothy Murphy, B.A. THESIS FOR THE DEGREE OF PH.D. DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF IRELAND MAYNOOTH HEAD OF DEPARTMENT: Professor Marian Lyons Supervisor of Research: Dr. Ian Speller October 2010 i DEDICATION To my Grandparents, John and Teresa Blake. ii CONTENTS Page No. Title page i Dedication ii Contents iii Acknowledgements iv List of Abbreviations vi Introduction 1 Chapter 1: The ‗greatest calamity that could befall a country‘ 23 Chapter 2: Emergency Powers: The 1922 Public Safety Resolution 62 Chapter 3: A ‗Damned Englishman‘: The execution of Erskine Childers 95 Chapter 4: ‗Terror Meets Terror‘: Assassination and Executions 126 Chapter 5: ‗executions in every County‘: The decentralisation of public safety 163 Chapter 6: ‗The serious situation which the Executions have created‘ 202 Chapter 7: ‗Extraordinary Graveyard Scenes‘: The 1924 reinterments 244 Conclusion 278 Appendices 299 Bibliography 323 iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to extend my most sincere thanks to many people who provided much needed encouragement during the writing of this thesis, and to those who helped me in my research and in the preparation of this study. In particular, I am indebted to my supervisor Dr. Ian Speller who guided me and made many welcome suggestions which led to a better presentation and a more disciplined approach. I would also like to offer my appreciation to Professor R. V. Comerford, former Head of the History Department at NUI Maynooth, for providing essential advice and direction. Furthermore, I would like to thank Professor Colm Lennon, Professor Jacqueline Hill and Professor Marian Lyons, Head of the History Department at NUI Maynooth, for offering their time and help. -

HU1 MAYNOOTH Oitecoil R»A Heirearwi M I Nuad

L'O ^tS-U HU1 MAYNOOTH Oitecoil r»a hEirearwi M i Nuad THE IMPACT OF EX BRITISH SOLDIERS ON THE I RISH VOLUNTEERS AND FREE STATE ARMY 1913-1924 BY MICHAEL JOSEPH WHELAN IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MA DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF IRELAND MAYNOOTH HEAD OF DEPARTMENT: PROFESSOR R.V.COMERFORD SUPERVISOR OF RESEARCH: DR IAN SPELLER July 2006 Abstract The aim of this thesis is to highlight the service of ex-British soldiers in the Irish Army and to examine some of their experiences during the period 1913-1924 with particular emphasis on the Irish Civil War. There was a constant utilisation of ex-British servicemen for their skills and also their intimidation by republicans throughout the period but their involvement may have been one of the factors that helped the IRA to bring the British government to negotiate. This is also true for the Free State Army and its defeat of the IRA during the Civil War. The Irish Volunteers and IRA was a guerrilla force combating a conventional army in many cases by using British military skills learned from ex-British soldiers. The Free State Army fought the IRA, which it had also evolved from, portraying a conventional military force using many more ex-British soldiers and lessons they had learned from the War of Independence against the British and those learned during the Great War. The ex-British soldiers helped to transform the army from a guerrilla force into a conventional army and it was probably their impact that had the greatest influence on the Irish Free State Army in defeating the republican forces and helped win the Irish Civil War.