Second Naivete and Mature Zionism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Ideology of Internationalism in David Ben-Gurion's

Statesman or Internationalist?: The Ideology of Internationalism in David Ben-Gurion’s Imagined Transnational Community, 1900 – 1931 Ari Cohen Master’s Thesis Corcoran Department of History University of Virginia January 2018 Introduction In 1983 Benedict Anderson wrote, “Nation-ness is the most universally legitimate value in the political life of our time.”1 His seminal book, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism, contended that nationalism shaped the modern world by creating independent political units of nation-states still visible today. The nation comprised Anderson’s sole unit of measure for global modern politics. Anderson’s thesis defined two generations of historians who focused on nations and their construction in the post-imperial period: ideologically, geographically, culturally, and intellectually, in minds and along borders. This historical trend produced vital explorations of the 1 Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism (Place: Publisher, 1983), 3. 1 fundamental transition from empires to modern states. It accounted for the creation of modern nation-states and for the nationalist movements that reordered a broken world system. Still, the Anderson approach was not without its critics. Many scholars challenged his stark view of nationalism as an imaginary construct of modernity, which excluded the possibility for premodern nations and national identities.2 Others questioned his narrow focus on print capitalism as a key driver of the nation-formation process.3 These critiques centered on the causes of nationalism and its periodization. More recently, however, a third more expansive line of critique has appeared. As recent scholarship has demonstrated, Anderson explicitly viewed nation-states as atomized units. -

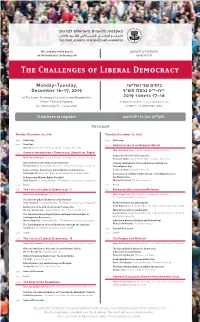

The Challenges of Liberal Democracy

אנו מתכבדים להזמינכם We cordially invite you to לכינוס בנושא an international conference on The Challenges of Liberal Democracy בימים שני ושלישי, ,Monday–Tuesday י"ח-י"ט בכסלו תש"ף December 16–17, 2019 17-16 בדצמבר at The Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities 2019 בבית האקדמיה, כיכר אלברט איינשטיין, ,Albert Einstein Square רחוב ז‘בוטינסקי 43, ירושלים Jabotinsky St., Jerusalem 43 הקליקו כאן כדי להירשם Click here to register Program Monday, December 16, 2019 Tuesday, December 17, 2019 08:30 Gathering 09:00 Gathering 09:00 Greetings 09:30 Democracies in an Unequal World Nili Cohen, President of the Academy; Tel Aviv University Chair: Benjamin Isaac, Academy Member; Tel Aviv University 09:15 General Introduction – Democracy, Liberalism, Rights Inequality in Historical Perspective Chair: Avishai Margalit, Academy Member; The Hebrew University of Jerusalem Shulamit Volkov, Academy Member; Tel Aviv University Liberal Democracy: Values and Institutions Citizens and Subjects: Voice and Representation in a Shlomo Avineri, Academy Member; The Hebrew University of Jerusalem Technological Age Representative Democracy: Vulnerabilities and Resilience Sheila Jasanoff, Harvard University Dominique Moisi, Institut Français des Relations Internationales Democracy in a Digital-Global Society: Technology Giants vs. Is Democracy Without Rights Possible? the Nation State Ruth Gavison, Academy Member; The Hebrew University of Jerusalem Michael Birnhack, Tel Aviv University 10:45 Break 11:00 Break 11:15 The Crisis of Liberal Democracy – I 11:30 Between Liberalism -

Zeev Sternhell

1 Prof. Zeev Sternhell From Anti-Enlightenment to Fascism and Nazism: Reflections on the Road to Genocide The purpose of this short presentation is a reflection on the road to the Holocaust and on the universal aspects of Genocide. It is a reflection on the consequences of two centuries of war against the Enlightenment, the rights of man, the idea of equality, it is a reflection on the 20th century European catastrophe and ultimately on the culture of our time. First of all let me make clear that despite the fact that the Great War is more and more commonly seen as the end of the 19th century and the matrix of the 20th century, the 20th century I am referring to came into being with the intellectual, scientific and technological revolution that preceded August 1914 by 30 years. The turn of the 20th century was one of the most fascinating and most revolutionary periods in modern history: the technological revolution, while transforming the face of the continent, greatly changed the nature of existence. From our perspective today it is important to understand how deeply the scientific revolution overturned the view men had of themselves and of the universe they inhabited. A real intellectual revolution prepared the convulsions which were soon to produce the European disaster of the first half of the 20th century. Indeed, right in the midst of a period of unprecedented scientific and technological progress, the rejection of Enlightenment's humanism, of rationalism, universalism and the idea of the rights of man reached a point of culmination and was followed by a similar rejection of the Christian vision of man. -

Barriers to Peace in the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict

The Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies Founded by the Charles H. Revson Foundation Barriers to Peace in the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict Editor: Yaacov Bar-Siman-Tov 2010 Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies – Study no. 406 Barriers to Peace in the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict Editor: Yaacov Bar-Siman-Tov The statements made and the views expressed are solely the responsibility of the authors. © Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung Israel 6 Lloyd George St. Jerusalem 91082 http://www.kas.de/israel E-mail: [email protected] © 2010, The Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies The Hay Elyachar House 20 Radak St., 92186 Jerusalem http://www.jiis.org E-mail: [email protected] This publication was made possible by funds granted by the Charles H. Revson Foundation. In memory of Professor Alexander L. George, scholar, mentor, friend, and gentleman The Authors Yehudith Auerbach is Head of the Division of Journalism and Communication Studies and teaches at the Department of Political Studies of Bar-Ilan University. Dr. Auerbach studies processes of reconciliation and forgiveness . in national conflicts generally and in the Israeli-Palestinian context specifically and has published many articles on this issue. Yaacov Bar-Siman-Tov is a Professor of International Relations at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and holds the Chair for the Study of Peace and Regional Cooperation. Since 2003 he is the Head of the Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies. He specializes in the fields of conflict management and resolution, peace processes and negotiations, stable peace, reconciliation, and the Arab-Israeli conflict in particular. He is the author and editor of 15 books and many articles in these fields. -

Lost Opportunities for Peace in the Arab- Israeli Conºict

Lost Opportunities for Jerome Slater Peace in the Arab- Israeli Conºict Israel and Syria, 1948–2001 Until the year 2000, during which both the Israeli-Palestinian and Israeli-Syrian negotiating pro- cesses collapsed, it appeared that the overall Arab-Israeli conºict was ªnally going to be settled, thus bringing to a peaceful resolution one of the most en- during and dangerous regional conºicts in recent history.The Israeli-Egyptian conºict had concluded with the signing of the 1979 Camp David peace treaty, the Israeli-Jordanian conºict had formally ended in 1994 (though there had been a de facto peace between those two countries since the end of the 1967 Arab-Israeli war), and both the Israeli-Palestinian and Israeli-Syrian conºicts seemedLost Opportunities for Peace on the verge of settlement. Yet by the end of 2000, both sets of negotiations had collapsed, leading to the second Palestinian intifada (uprising), the election of Ariel Sharon as Israel’s prime minister in February 2001, and mounting Israeli-Palestinian violence in 2001 and 2002.What went wrong? Much attention has been focused on the lost 1 opportunity for an Israeli-Palestinian settlement, but surprisingly little atten- tion has been paid to the collapse of the Israeli-Syrian peace process.In fact, the Israeli-Syrian negotiations came much closer to producing a comprehen- Jerome Slater is University Research Scholar at the State University of New York at Buffalo.Since serving as a Fulbright scholar in Israel in 1989, he has written widely on the Arab-Israeli conºict for professional journals such as the Jerusalem Journal of International Relations and Political Science Quarterly. -

From Left to Right: Israel's Repositioning in the World

2015 年 3 月 第 2 号 The 2nd volume 【編集ボード】 委員長: 鈴木均 内部委員: 土屋一樹、Housam Darwisheh、渡邊祥子、石黒大岳 外部委員: 清水学、内藤正典、池内恵 本誌に掲載されている論文などの内容や意見は、外部からの論稿を含め、執筆者 個人に属すものであり、日本貿易振興機構あるいはアジア経済研究所の公式見解を 示すものではありません。 中東レビュー 第 2 号 2015 年 3 月 16 日発行Ⓒ 編集: 『中東レビュー』編集ボード 発行: アジア経済研究所 独立行政法人日本貿易振興機構 〒261-8545 千葉県千葉市美浜区若葉 3-2-2 URL: http://www.ide.go.jp/Japanese/Publish/Periodicals/Me_review/ ISSN: 2188-4595 IDE ME Review Vol.2 (2014-2015) FROM LEFT TO RIGHT: ISRAEL’S REPOSITIONING IN THE WORLD 左から右へ: イスラエルの政治的な長期傾向 Yakov M. Rabkin* 第二次大戦時に大量のユダヤ人避難民を受け入れたイスラエルは、1946 年の建 国時には共産主義的な社会改革思想に基づくキブツ運動などの左翼的思潮を国家 建設の支柱にしていたが、その後の政治過程のなかで一貫して右傾化の方向をたど り、現在では国際的にみても最も保守的な軍事主義的思想傾向が国民のあいだで広 く共有され、国内のアラブ系住民の経済的従属が永く固定化するに至った。 現在のイスラエル国家を思想的にも実体経済的にも支えている基本的な理念は、 建国時のそれとは全く対極的な新保守主義とグローバル化された「新自由主義」的な 資本主義であり、それは当然ながら国内における安価な労働力としてのアラブ系住民 の存在を所与の前提条件として組み込んでいる。 これは具体的にどのような経緯によるものであり、またイスラエル国家のどのような性 格から導き出されるものなのか。本論稿では政治的シオニズムがイスラエル建国後か ら現在までにたどってきた思想的な系譜を改めて確認し、現在のイスラエルが国際的 に置かれている特異な立場とその背後にある諸要因を説明する。 * Professor of History, University of Montreal. His two recent books are: A Threat from Within: A Century of Jewish Opposition to Zionism (Palgrave Macmillan/Zed Books) that appeared in fifteen languges and and Compendre l’État d’Israël (Écosociété). Both have been published in Japanese by Heibonsha. FROM LEFT TO RIGHT: ISRAEL’S REPOSITIONING IN THE WORLD In its pioneer years, Israel 1 was largely associated with the leftist ideas of collective endeavour and socialist solidarity. Early Israeli elites often came from the kibbutz and were vocal in their allegiance to social justice and equality. This, in turn, brought them admiration and support from socialists around the world. Few noticed that while praised by the left, Israeli society was steadily moving to right. Nowadays Israel has earned the admiration of the right and the extreme right in most Western countries. This paper should explain this apparently puzzling transformation in the international position of this small country in Western Asia. -

Secularisation, Inter-Religious Dialogue and Democratisation in the Southern Mediterranean

CENTRE FOR EUROPEAN POLICY WORKING PAPER NO. 4 STUDIES APRIL 2003 Searching for Solutions SECULARISATION, INTER-RELIGIOUS DIALOGUE AND DEMOCRATISATION IN THE SOUTHERN MEDITERRANEAN THEODOROS KOUTROUBAS This is the fourth in a series of Working Papers published by the CEPS Middle East and Euro-Med Project. The project addresses issues of policy and strategy of the European Union in relation to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and the wider issues of EU relations with the countries of the Barcelona Process and the Arab world. Participants in the project include independent experts from the region and the European Union, as well as a core team at CEPS in Brussels led by Michael Emerson and Nathalie Tocci. Support for the project is gratefully acknowledged from: • Compagnia di San Paolo, Torino • Department for International Development (DFID), London. Unless otherwise indicated, the views expressed are attributable only to the author in a personal capacity and not to any institution with which he is associated. ISBN 92-9079-426-7 Available for free downloading from the CEPS website (http://www.ceps.be) © Copyright 2003, CEPS CEPS Middle East & Euro-Med Project Centre for European Policy Studies Place du Congrès 1 • B-1000 Brussels • Tel: (32.2) 229.39.11 • Fax: (32.2) 219.41.41 e-mail: [email protected] • website: http://www.ceps.be SECULARISATION, INTER-RELIGIOUS DIALOGUE AND DEMOCRATISATION IN THE SOUTHERN MEDITERRANEAN WORKING PAPER NO. 4 OF THE CEPS MIDDLE EAST & EURO-MED PROJECT * THEODOROS KOUTROUBAS ABSTRACT The paper discusses the relation between religion and politics in the Southern Mediterranean and its consequences for the democratisation and peaceful co-existence of the different confessional communities of the region. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title History in the Public Courtroom: Commissions of Inquiry and Struggles over the History and Memory of Israeli Traumas Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3vf2g7r0 Author Molchadsky, Nadav Gadi Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles History in the Public Courtroom: Commissions of Inquiry and Struggles over the History and Memory of Israeli Traumas A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In History by Nadav Gadi Molchadsky 2015 © Copyright by Nadav Gadi Molchadsky 2015 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION History in the Public Courtroom: Commissions of Inquiry and Struggles over the History and Memory of Israeli Traumas by Nadav Gadi Molchadsky Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Los Angeles, 2015 Professor David N. Myers, Co-Chair Professor Arieh B. Saposnik, Co-Chair This study seeks to shed new light on the complex web of relations among history, historiography and contemporary life. It does so by focusing on Israeli commissions of inquiry that have taken rise in the wake of major national traumas such as failed battles in the 1948 War, the Yom Kippur War, and the assassination of the Zionist leader Chaim Arlosoroff. Each one of these landmark events in the history of Israel was investigated by a state or a military commission of inquiry, whose members and audience operate as authors of history and agents of memory. The study suggests that commissions of inquiry, which have been studied to date primarily as legal, administrative, and political bodies, in fact also operate as a public historian of a unique kind. -

The Challenge of Post-Zionism: Alternatives to Israeli Fundamentalist Politics Ephraim Nimni London: Zed Books, 2003

120 The American Journal of Islamic Social Sciences 22:3 The Challenge of Post-Zionism: Alternatives to Israeli Fundamentalist Politics Ephraim Nimni London: Zed Books, 2003. 209 pages. In uttering “Everywhere I wander is Jerusalem,” the late nineteenth-century Hasidic revolutionary, Nahman of Bratzlav, was the first post-Zionist. The thought-provoking essays in this anthology, especially the conclusion, address the shifting signification of post-Zionism from (1) a methodology in the Israeli social sciences, (2) to the political trends within contemporary Book Reviews 121 Israeli society, and (3) to a particular period/project of the Israeli polity/ society (p. 183). Rounding out the volume are the 1998 reflections of renowned Palestinian thinker, Edward Said, “New History, Old Ideas” (pp. 199-202). This is his critique of a Palestinian-Israeli conference featuring “new” Israeli historians and their Palestinian counterparts, which included Elie Sambar, Nur Masalha, and himself, as well as Benny Morris, Ilan Pappé, Itamar Rabinowitch, and Zeev Sternhell. The present anthology is born from Said’s critique of those who con- cluded that it was morally wrong but necessary to expel the Palestinians in tandem with Zionist efforts to reestablish the Jewish state. Of this group, only Pappé resists the profound contradiction, bordering on schizophrenia (p. 200), that informs all other research of these “new” historians. Calling for Palestinian and Arab intellectuals to engage Israeli academic and intel- lectual audiences by lecturing in Israeli centers openly, while admitting that the years of boycotting have achieved little (p. 202), Said calls for a new politics free of racial prejudices and ostrich-like attitudes. -

Neo-Socialism and the Fascist Destiny of an Anti-Fascist Discourse

"Order, Authority, Nation": Neo-Socialism and the Fascist Destiny of an Anti-Fascist Discourse by Mathieu Hikaru Desan A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Sociology) in the University of Michigan 2016 Doctoral Committee: Professor George Steinmetz, Chair Professor Howard Brick Assistant Professor Robert S. Jansen Emeritus Professor Howard Kimeldorf Professor Gisèle Sapiro Centre national de la recherche scientifique/École des hautes études en sciences sociales Acknowledgments Scholarly production is necessarily a collective endeavor. Even during the long isolated hours spent in dusty archives, this basic fact was never far from my mind, and this dissertation would be nothing without the community of scholars and friends that has nourished me over the past ten years. First thanks are due to George Steinmetz, my advisor and Chair. From the very beginning of my time as a graduate student, he has been my intellectual role model. He has also been my champion throughout the years, and every opportunity I have had has been in large measure thanks to him. Both his work and our conversations have been constant sources of inspiration, and the breadth of his knowledge has been a vital resource, especially to someone whose interests traverse disciplinary boundaries. George is that rare sociologist whose theoretical curiosity and sophistication is matched only by the lucidity of this thought. Nobody is more responsible for my scholarly development than George, and all my work bears his imprint. I will spend a lifetime trying to live up to his scholarly example. I owe him an enormous debt of gratitude. -

European Fascism Since 1919

PAPER 20. EUROPEAN FASCISM SINCE 1919 Introduction Fascism was the most consequential political invention of the twentieth century. Its challenge to the liberal, capitalist order of Europe was more momentous – and murderous – than that of communism. The terror and destruction unleashed by the major fascist regimes have left an indelible mark on the course of modern history and our collective memory. The symbols and imagery of fascism remain instantly recognizable, while its ideas have seen a remarkable renaissance in the past twenty years. Despite this enormous impact, fascism has proved strangely elusive as an object of historical analysis. Since 1945, it has been frequently explained away as a political pathology: a horrific, but fleeting deviation from Europe‟s path to modernity. Marxist commentators in particular have downplayed its significance by reducing it to a mere reflection of the „disintegrating bourgeois state‟. Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, German (as well as Italian) historians insisted that „their‟ brand of fascism was so much more (or less) extreme than other variants that comparative interpretations were morally reprehensible (or lacking in heuristic value). Today, after a decade of renewed academic interest in „generic fascism‟, prompted by the works of Roger Griffin, Stanley Payne and Zeev Sternhell, there is still considerable scholarly hostility to the notion that fascism represented a serious alternative to parliamentary democracy and the free market on the one hand and communism on the other. Paper 20 takes fascism seriously. It provides a sober, scrupulous recharting of the fascist „third way‟, beyond the ira et studium of the anti-fascists and the pieties of the Sonderweg theorists. -

Education, Fascism, and the Catholic Church in Franco's Spain

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 2011 Education, Fascism, and the Catholic Church in Franco's Spain Joan Domke Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Part of the Educational Administration and Supervision Commons Recommended Citation Domke, Joan, "Education, Fascism, and the Catholic Church in Franco's Spain" (2011). Dissertations. 104. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/104 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 2011 Joan Domke LOYOLA UNIVERSITY CHICAGO EDUCATION, FASCISM, AND THE CATHOLIC CHURCH IN FRANCO‟S SPAIN A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY PROGRAM IN CULTURAL AND EDUCATIONAL POLICY STUDIES BY JOAN CICERO DOMKE CHICAGO, IL MAY 2011 Copyright by Joan Domke, 2011 All rights reserved. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank Sr. Salvador Vergara, of the Instituto Cervantes in Chicago, for his untiring assistance in providing the most current and pertinent sources for this study. Also, Mrs. Nicia Irwin, of Team Expansion in Granada, Spain, made it possible, through her network of contacts, for present-day Spaniards to be an integral part in this research. Dr. Katherine Carroll gave me invaluable advice in the writing of the manuscript and Dr. John Cicero helped in the area of data analysis.