The Ideology of Internationalism in David Ben-Gurion's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Survey of Textbooks Most Commonly Used to Teach the Arab-Israeli

A Critical Survey of Textbooks on the Arab-Israeli and Israeli-Palestinian Conflict Working Paper No. 1 │ April 2017 Uzi Rabi Chelsi Mueller MDC Working Paper Series The views expressed in the MDC Working Paper Series are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the Moshe Dayan Center for Middle Eastern and African Studies or Tel Aviv University. MDC Working Papers have not undergone formal review and approval. They are circulated for discussion purposes only. Their contents should be considered preliminary and are not to be reproduced without the authors' permission. Please address comments and inquiries about the series to: Dr. Chelsi Mueller Research Fellow The MDC for Middle Eastern and African Studies Tel Aviv University Ramat Aviv, 6997801 Israel Email: [email protected] Tel: +972-3-640-9100 US: +1-617-787-7131 Fax: +972-3-641-5802 MDC Working Paper Series Acknowledgements The authors would like to thank the research assistants and interns who have contributed significantly to this research project. Eline Rosenhart was with the project from the beginning to end, cataloging syllabi, constructing charts, reading each text from cover to cover, making meticulous notes, transcribing meetings and providing invaluable editorial assistance. Rebekka Windus was a critical eye and dedicated consultant during the year-long reading phase of the project. Natasha Spreadborough provided critical comments and suggestions that were very instrumental during the reading phase of this project. Ben Mendales, the MDC’s project management specialist, was exceptionally receptive to the needs of the team and provided vital logistical support. Last but not least, we are deeply grateful to Prof. -

Aliyah and Settlement Process?

Jewish Women in Pre-State Israel HBI SERIES ON JEWISH WOMEN Shulamit Reinharz, General Editor Joyce Antler, Associate Editor Sylvia Barack Fishman, Associate Editor The HBI Series on Jewish Women, created by the Hadassah-Brandeis Institute, pub- lishes a wide range of books by and about Jewish women in diverse contexts and time periods. Of interest to scholars and the educated public, the HBI Series on Jewish Women fills major gaps in Jewish Studies and in Women and Gender Studies as well as their intersection. For the complete list of books that are available in this series, please see www.upne.com and www.upne.com/series/BSJW.html. Ruth Kark, Margalit Shilo, and Galit Hasan-Rokem, editors, Jewish Women in Pre-State Israel: Life History, Politics, and Culture Tova Hartman, Feminism Encounters Traditional Judaism: Resistance and Accommodation Anne Lapidus Lerner, Eternally Eve: Images of Eve in the Hebrew Bible, Midrash, and Modern Jewish Poetry Margalit Shilo, Princess or Prisoner? Jewish Women in Jerusalem, 1840–1914 Marcia Falk, translator, The Song of Songs: Love Lyrics from the Bible Sylvia Barack Fishman, Double or Nothing? Jewish Families and Mixed Marriage Avraham Grossman, Pious and Rebellious: Jewish Women in Medieval Europe Iris Parush, Reading Jewish Women: Marginality and Modernization in Nineteenth-Century Eastern European Jewish Society Shulamit Reinharz and Mark A. Raider, editors, American Jewish Women and the Zionist Enterprise Tamar Ross, Expanding the Palace of Torah: Orthodoxy and Feminism Farideh Goldin, Wedding Song: Memoirs of an Iranian Jewish Woman Elizabeth Wyner Mark, editor, The Covenant of Circumcision: New Perspectives on an Ancient Jewish Rite Rochelle L. -

Israeli Historiograhy's Treatment of The

Yechiam Weitz Dialectical versus Unequivocal Israeli Historiography’s Treatment of the Yishuv and Zionist Movement Attitudes toward the Holocaust In November 1994, I helped organize a conference called “Vision and Revision.” Its subject was to be “One Hundred Years of Zionist Histo- riography,”1 but in fact it focused on the stormy debate between Zionists and post-Zionists or Old and New Historians, a theme that pervaded Is- rael’s public and academic discourse at the time. The discussion revolved around a number of topics and issues, such as the birth of the Arab refugee question in the War of Independence and matters concerning the war itself. Another key element of the controversy involved the attitude of the Yishuv (the Jewish community in prestate Israel) and the Zionist move- ment toward the Holocaust. There were several parts to the question: what was the goal of the Yishuv and the Zionist leadership—to save the Jews who were perishing in smoldering Europe or to save Zionism? What was more important to Zionism—to add a new cowshed at Kib- butz ‘Ein Harod and purchase another dunam of land in the Negev or Galilee or the desperate attempt to douse the European inferno with a cup of water? What, in those bleak times, motivated the head of the or- ganized Yishuv, David Ben-Gurion: “Palestinocentrism,” and perhaps even loathing for diaspora Jewry, or the agonizing considerations of a leader in a period of crisis unprecedented in human history? These questions were not confined to World War II and the destruc- tion of European Jewry (1939–45) but extended back to the 1930s and forward to the postwar years. -

Second Naivete and Mature Zionism

"Honoring Tradition, Celebrating Diversity, and Building a Jewish Future" 1301 Oxford Street - Berkeley 94709 510-848-3988 www.bethelberkeley.org Second Naiveté and Mature Zionism Rabbi Yoel H. Kahn Congregation Beth El Berkeley, California Kol Nidre 5776 September 23, 2015 ©Yoel H. Kahn 2015 Do you remember discovering for the first time that your parents could be really, really wrong? And a little later, after taking that in, realizing that you could still love them? The French philosopher Paul Ricoeur taught about the arc of faith development – and how we can gain wisdom – over the lifespan. When we are very young, our parents are the source of guidance and the font of care and goodness. We may remember our own experience as young children, or as the parents of young children – the joy and comfort when reuniting with a parent after even a short separation. For the little child, the parent can do no wrong and we take literally what they say about the world. In the context of religious faith, which is actually where Ricoeur maps this process, this stage is called first naiveté – when we accept the stories, texts and received teachings of our tradition at their literal, face value. The adolescent comes to see the world more widely. Having gained a perspective on the world through encounters with literature and culture, teachers and other adults, we may come to fault our parents and be disappointed in them. We realize that there are multiple points of view and alternative paths to explaining and moving through the world. This is the stage of alienation and distance – as we establish ourselves as separate people, we need to grieve the loss of innocence, letting go of that original naiveté. -

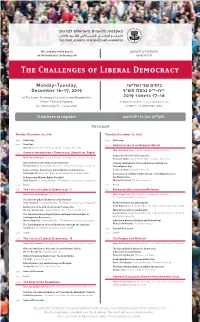

The Challenges of Liberal Democracy

אנו מתכבדים להזמינכם We cordially invite you to לכינוס בנושא an international conference on The Challenges of Liberal Democracy בימים שני ושלישי, ,Monday–Tuesday י"ח-י"ט בכסלו תש"ף December 16–17, 2019 17-16 בדצמבר at The Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities 2019 בבית האקדמיה, כיכר אלברט איינשטיין, ,Albert Einstein Square רחוב ז‘בוטינסקי 43, ירושלים Jabotinsky St., Jerusalem 43 הקליקו כאן כדי להירשם Click here to register Program Monday, December 16, 2019 Tuesday, December 17, 2019 08:30 Gathering 09:00 Gathering 09:00 Greetings 09:30 Democracies in an Unequal World Nili Cohen, President of the Academy; Tel Aviv University Chair: Benjamin Isaac, Academy Member; Tel Aviv University 09:15 General Introduction – Democracy, Liberalism, Rights Inequality in Historical Perspective Chair: Avishai Margalit, Academy Member; The Hebrew University of Jerusalem Shulamit Volkov, Academy Member; Tel Aviv University Liberal Democracy: Values and Institutions Citizens and Subjects: Voice and Representation in a Shlomo Avineri, Academy Member; The Hebrew University of Jerusalem Technological Age Representative Democracy: Vulnerabilities and Resilience Sheila Jasanoff, Harvard University Dominique Moisi, Institut Français des Relations Internationales Democracy in a Digital-Global Society: Technology Giants vs. Is Democracy Without Rights Possible? the Nation State Ruth Gavison, Academy Member; The Hebrew University of Jerusalem Michael Birnhack, Tel Aviv University 10:45 Break 11:00 Break 11:15 The Crisis of Liberal Democracy – I 11:30 Between Liberalism -

Institute for Palestine Studies | Journals

Institute for Palestine Studies | Journals Journal of Palestine Studies issue 141, published in Fall 2006 The 1948 Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine by Ilan Pappé This article, excerpted and adapted from the early chapters of a new book, emphasizes the systematic preparations that laid the ground for the expulsion of more than 750,000 Palestinians from what became Israel in 1948. While sketching the context and diplomatic and political developments of the period, the article highlights in particular a multi-year “Village Files” project (1940–47) involving the systematic compilation of maps and intelligence for each Arab village and the elaboration—under the direction of an inner “caucus” of fewer than a dozen men led by David Ben-Gurion—of a series of military plans culminating in Plan Dalet, according to which the 1948 war was fought. The article ends with a statement of one of the author’s underlying goals in writing the book: to make the case for a paradigm of ethnic cleansing to replace the paradigm of war as the basis for the scholarly research of, and the public debate about, 1948. ILAN PAPPÉ, an Israeli historian and professor of political science at Haifa University, is the author of a number of books, including The Making of the Arab-Israeli Conflict, 1947–1951 (I. B. Tauris, 1994) and A History of Modern Palestine: One Land, Two Peoples (Cambridge University Press, 2004). The current article is extracted from early chapters of his latest book, The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine (Oneworld Publications, Oxford, England, forthcoming in October 2006). THE 1948 ETHNIC CLEANSING OF PALESTINE ILAN PAPPÉ This article, excerpted and adapted from the early chapters of a new book, emphasizes the systematic preparations that laid the ground for the expulsion of more than 750,000 Palestinians from what became Israel in 1948. -

Comrades and Enemies Lockman.Pdf

Comrades and Enemies Preferred Citation: Lockman, Zachary. Comrades and Enemies: Arab and Jewish Workers in Palestine, 1906-1948. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1996 1996. http://ark.cdlib.org/ ark:/13030/ft6b69p0hf/ Comrades and Enemies Arab and Jewish Workers in Palestine, 1906–1948 Zachary Lockman UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS Berkeley · Los Angeles · London © 1996 The Regents of the University of California For my father, Michael Lockman (1912–1994), and my daughter, Talya Mara Lockman-Fine Preferred Citation: Lockman, Zachary. Comrades and Enemies: Arab and Jewish Workers in Palestine, 1906-1948. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1996 1996. http://ark.cdlib.org/ ark:/13030/ft6b69p0hf/ For my father, Michael Lockman (1912–1994), and my daughter, Talya Mara Lockman-Fine Acknowledgments Many people and institutions contributed in different ways to the research, thinking, and writing that went into this book. Though I cannot hope to thank all of them properly, I would like at least to mention those who contributed most significantly and directly, though none of them bears any responsibility for my analyses or judgments in this book, or for any errors it may contain. I carried out the bulk of the archival and library research for this book in Israel. A preliminary trip was funded by a faculty research support grant from the Harvard Graduate Society, while an extended stay in 1987 was made possible by a fellowship from the Fulbright Scholar Program. A fellowship from the Social Science Research Council supported research in the United Kingdom. In Israel I spent a great deal of time at the Histadrut archives, known formally as Arkhiyon Ha‘avoda Vehehalutz, at the Makhon Lavon Leheker Tnu‘at Ha‘avoda in Tel Aviv. -

Zeev Sternhell

1 Prof. Zeev Sternhell From Anti-Enlightenment to Fascism and Nazism: Reflections on the Road to Genocide The purpose of this short presentation is a reflection on the road to the Holocaust and on the universal aspects of Genocide. It is a reflection on the consequences of two centuries of war against the Enlightenment, the rights of man, the idea of equality, it is a reflection on the 20th century European catastrophe and ultimately on the culture of our time. First of all let me make clear that despite the fact that the Great War is more and more commonly seen as the end of the 19th century and the matrix of the 20th century, the 20th century I am referring to came into being with the intellectual, scientific and technological revolution that preceded August 1914 by 30 years. The turn of the 20th century was one of the most fascinating and most revolutionary periods in modern history: the technological revolution, while transforming the face of the continent, greatly changed the nature of existence. From our perspective today it is important to understand how deeply the scientific revolution overturned the view men had of themselves and of the universe they inhabited. A real intellectual revolution prepared the convulsions which were soon to produce the European disaster of the first half of the 20th century. Indeed, right in the midst of a period of unprecedented scientific and technological progress, the rejection of Enlightenment's humanism, of rationalism, universalism and the idea of the rights of man reached a point of culmination and was followed by a similar rejection of the Christian vision of man. -

Barriers to Peace in the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict

The Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies Founded by the Charles H. Revson Foundation Barriers to Peace in the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict Editor: Yaacov Bar-Siman-Tov 2010 Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies – Study no. 406 Barriers to Peace in the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict Editor: Yaacov Bar-Siman-Tov The statements made and the views expressed are solely the responsibility of the authors. © Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung Israel 6 Lloyd George St. Jerusalem 91082 http://www.kas.de/israel E-mail: [email protected] © 2010, The Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies The Hay Elyachar House 20 Radak St., 92186 Jerusalem http://www.jiis.org E-mail: [email protected] This publication was made possible by funds granted by the Charles H. Revson Foundation. In memory of Professor Alexander L. George, scholar, mentor, friend, and gentleman The Authors Yehudith Auerbach is Head of the Division of Journalism and Communication Studies and teaches at the Department of Political Studies of Bar-Ilan University. Dr. Auerbach studies processes of reconciliation and forgiveness . in national conflicts generally and in the Israeli-Palestinian context specifically and has published many articles on this issue. Yaacov Bar-Siman-Tov is a Professor of International Relations at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and holds the Chair for the Study of Peace and Regional Cooperation. Since 2003 he is the Head of the Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies. He specializes in the fields of conflict management and resolution, peace processes and negotiations, stable peace, reconciliation, and the Arab-Israeli conflict in particular. He is the author and editor of 15 books and many articles in these fields. -

Of Benny Morris: Morality in the History of 1948 and the Creation of the Palestinian-Refugee Crisis

The “Conversion” of Benny Morris: Morality in the History of 1948 and the Creation of the Palestinian-Refugee Crisis JOSIE GRAY The history surrounding the 1948 War and the creation of the Palestinian- refugee crisis continues to be contentious, political, and filled with questions of morality. This is especially true for Benny Morris’s historical work. As an Israeli historian, Morris has made significant contributions to the historiography of 1948, with most of his work focusing on the role that Jewish forces played in the expulsion of Palestinian Arabs in 1948 (something that the Israeli government had denied vehemently). Although celebrated for his historical work, following the collapse of the Palestinian-Israeli peace process in the early 2000s Morris publically announced his support for the expulsion of Palestinians in 1948 and argued that Jewish forces should have expelled every single Palestinian Arab. This paper discusses how a dual commitment to honest historical study and Zionism allowed Morris to announce his support for the atrocities that his own research had uncovered. On November 29, 1947, the United Nations General Assembly passed Resolution 181, which approved the partition of Mandate Palestine, which had been under British rule since 1920. Although Arabs made up seventy-one per cent of the population, the partition plan allotted fifty-six per cent of the territory to a Jewish state with the Palestinian state receiving forty-two per cent.1 The proposed Jewish state would contain 499,000 Jews and 438,000 Arabs—a bare majority—while the proposed Palestinian state would have 818,000 Arabs and 10,000 Jews.2 The Jewish leadership accepted this plan; Arab representatives rejected it. -

Lost Opportunities for Peace in the Arab- Israeli Conºict

Lost Opportunities for Jerome Slater Peace in the Arab- Israeli Conºict Israel and Syria, 1948–2001 Until the year 2000, during which both the Israeli-Palestinian and Israeli-Syrian negotiating pro- cesses collapsed, it appeared that the overall Arab-Israeli conºict was ªnally going to be settled, thus bringing to a peaceful resolution one of the most en- during and dangerous regional conºicts in recent history.The Israeli-Egyptian conºict had concluded with the signing of the 1979 Camp David peace treaty, the Israeli-Jordanian conºict had formally ended in 1994 (though there had been a de facto peace between those two countries since the end of the 1967 Arab-Israeli war), and both the Israeli-Palestinian and Israeli-Syrian conºicts seemedLost Opportunities for Peace on the verge of settlement. Yet by the end of 2000, both sets of negotiations had collapsed, leading to the second Palestinian intifada (uprising), the election of Ariel Sharon as Israel’s prime minister in February 2001, and mounting Israeli-Palestinian violence in 2001 and 2002.What went wrong? Much attention has been focused on the lost 1 opportunity for an Israeli-Palestinian settlement, but surprisingly little atten- tion has been paid to the collapse of the Israeli-Syrian peace process.In fact, the Israeli-Syrian negotiations came much closer to producing a comprehen- Jerome Slater is University Research Scholar at the State University of New York at Buffalo.Since serving as a Fulbright scholar in Israel in 1989, he has written widely on the Arab-Israeli conºict for professional journals such as the Jerusalem Journal of International Relations and Political Science Quarterly. -

The War for Palestine: Rewriting the History of 1948

Published on Reviews in History (https://reviews.history.ac.uk) The War for Palestine: Rewriting the History of 1948 Review Number: 219 Publish date: Sunday, 30 September, 2001 Editor: Eugene Rogan Avi Shlaim ISBN: 9780521794765 Date of Publication: 2001 Pages: 249pp. Publisher: Cambridge University Press Place of Publication: Cambridge Reviewer: Matthew Hughes Introduction In an earlier review in the IHR 'Reviews in History' series (number 154) of Avi Shlaim's The Iron Wall: Israel and the Arab World (London: Allen Lane, 2000), I pointed to the intense historiographical conflict raging over the formation of Israel in 1948, the cause(s) of the Palestinian refugee crisis and the nature of Israel's subsequent relations with its Arab neighbours. For those readers unfamiliar with the debate, the essential fault line is between those who say that Israel was in some measure responsible for the Palestinian diaspora in 1948 and the subsequent Arab-Israeli conflict, and those who argue that the Palestinian refugee crisis was not, fundamentally, Israel's fault and that chances for peace were scuppered not by Israel but by obstinacy on the part of the Arabs. The debate has shifted over time. Until the 1970s it was dominated by an 'old' or 'mobilised' Israeli history that portrayed a Jewish state under serious threat from the Arabs and so reluctantly forced into a series of wars of survival. This changed in the 1980s with the arrival of what became known as the 'new' or 'revisionist' historians - sometimes also called the 'critical sociologists' - who offered radically contrary perspectives on the formation of Israel, the causes of the Palestinian refugee crisis and the origins of the Arab-Israeli wars.