Secularisation, Inter-Religious Dialogue and Democratisation in the Southern Mediterranean

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Ideology of Internationalism in David Ben-Gurion's

Statesman or Internationalist?: The Ideology of Internationalism in David Ben-Gurion’s Imagined Transnational Community, 1900 – 1931 Ari Cohen Master’s Thesis Corcoran Department of History University of Virginia January 2018 Introduction In 1983 Benedict Anderson wrote, “Nation-ness is the most universally legitimate value in the political life of our time.”1 His seminal book, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism, contended that nationalism shaped the modern world by creating independent political units of nation-states still visible today. The nation comprised Anderson’s sole unit of measure for global modern politics. Anderson’s thesis defined two generations of historians who focused on nations and their construction in the post-imperial period: ideologically, geographically, culturally, and intellectually, in minds and along borders. This historical trend produced vital explorations of the 1 Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism (Place: Publisher, 1983), 3. 1 fundamental transition from empires to modern states. It accounted for the creation of modern nation-states and for the nationalist movements that reordered a broken world system. Still, the Anderson approach was not without its critics. Many scholars challenged his stark view of nationalism as an imaginary construct of modernity, which excluded the possibility for premodern nations and national identities.2 Others questioned his narrow focus on print capitalism as a key driver of the nation-formation process.3 These critiques centered on the causes of nationalism and its periodization. More recently, however, a third more expansive line of critique has appeared. As recent scholarship has demonstrated, Anderson explicitly viewed nation-states as atomized units. -

1 Marieme Hélie-Lucas Oral History

Marieme Hélie-Lucas Oral History Content Summary Track 1 [duration: 1:10:05] [Session one: 7 July 2015] [00:00] Marieme Hélie-Lucas [MHL] Describes ‘feminist lineage’ and liberation struggle in Algeria as foundations. Born 1939, Algiers, Algeria. Describes upbringing by four women of different generations, never meeting biological father. Mentions mother’s divorce from violent man during pregnancy. Discusses common perceptions of fatherhood as psychotherapist, differentiating between biological parent and parent. Describes mother’s support from sister, mother and grandmother. Acknowledges being born into family of feminists as most important aspect of life. Compares to own experience of single motherhood, raising four children alone ‘in true sense of word’. Comments on loss of trans-generational solidarity in today’s society, disputing feminist belief that breaking from extended family liberating. Mentions viewpoint of friends from United States of America (USA). [05:08] Mother as first woman to divorce in family and immediate society. Describes great-grandmother as first feminist in lineage, managing business and six children following death of husband. Describes grandmother, born late 19th century. Mentions school compulsory in colonial Algeria, describing as free and secular. Story about grandmother being removed from school at critical moment in education, to help at home, raising youngest sibling, never forgiving parents and refusal to allow family influence on own daughters when widowed, instead taking menial jobs. [10:00] Continues story about grandmother, now working as office runner in customs office, pursuit of study, achieving qualification as customs inspector. Describes grandmother emphasising importance of economic independence to MHL’s mother and aunt. Remarks on mother’s feminist rebellion expressed in choice of unsuitable husband and then celibacy, observing that probably wanted child. -

Nostalgias in Modern Tunisia Dissertation

Images of the Past: Nostalgias in Modern Tunisia Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By David M. Bond, M.A. Graduate Program in Near Eastern Languages and Cultures The Ohio State University 2017 Dissertation Committee: Sabra J. Webber, Advisor Johanna Sellman Philip Armstrong Copyrighted by David Bond 2017 Abstract The construction of stories about identity, origins, history and community is central in the process of national identity formation: to mould a national identity – a sense of unity with others belonging to the same nation – it is necessary to have an understanding of oneself as located in a temporally extended narrative which can be remembered and recalled. Amid the “memory boom” of recent decades, “memory” is used to cover a variety of social practices, sometimes at the expense of the nuance and texture of history and politics. The result can be an elision of the ways in which memories are constructed through acts of manipulation and the play of power. This dissertation examines practices and practitioners of nostalgia in a particular context, that of Tunisia and the Mediterranean region during the twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. Using a variety of historical and ethnographical sources I show how multifaceted nostalgia was a feature of the colonial situation in Tunisia notably in the period after the First World War. In the postcolonial period I explore continuities with the colonial period and the uses of nostalgia as a means of contestation when other possibilities are limited. -

Second Naivete and Mature Zionism

"Honoring Tradition, Celebrating Diversity, and Building a Jewish Future" 1301 Oxford Street - Berkeley 94709 510-848-3988 www.bethelberkeley.org Second Naiveté and Mature Zionism Rabbi Yoel H. Kahn Congregation Beth El Berkeley, California Kol Nidre 5776 September 23, 2015 ©Yoel H. Kahn 2015 Do you remember discovering for the first time that your parents could be really, really wrong? And a little later, after taking that in, realizing that you could still love them? The French philosopher Paul Ricoeur taught about the arc of faith development – and how we can gain wisdom – over the lifespan. When we are very young, our parents are the source of guidance and the font of care and goodness. We may remember our own experience as young children, or as the parents of young children – the joy and comfort when reuniting with a parent after even a short separation. For the little child, the parent can do no wrong and we take literally what they say about the world. In the context of religious faith, which is actually where Ricoeur maps this process, this stage is called first naiveté – when we accept the stories, texts and received teachings of our tradition at their literal, face value. The adolescent comes to see the world more widely. Having gained a perspective on the world through encounters with literature and culture, teachers and other adults, we may come to fault our parents and be disappointed in them. We realize that there are multiple points of view and alternative paths to explaining and moving through the world. This is the stage of alienation and distance – as we establish ourselves as separate people, we need to grieve the loss of innocence, letting go of that original naiveté. -

Secularism, State Policies, and Muslims in Europe: Analyzing French 1 Exceptionalism Ahmet T

Comparative Politics Volume 41 Number 1 October 2008 Contents Secularism, State Policies, and Muslims in Europe: Analyzing French 1 Exceptionalism Ahmet T. Kuru Party Systems and Economic Policy Change in Postcommunist Democracies: 21 Ideological Consensus and Institutional Competition Shale Horowitz and Eric C. Browne Parties and Patronage: An Analysis of Trade and Industrial Policy in India 41 Charles R. Hankla When Does Participatory Democracy Deepen the Quality of Democracy? 61 Lessons from Brazil Brian Wampler Reducing the Perils of Presidentialism in Latin America through Presidential 83 Interruptions Leiv Marsteintredet and Einar Berntzen Review Article American Immigration through Comparativists’ Eyes 103 David D. Laitin Abstracts 121 Secularism, State Policies, and Muslims in Europe Analyzing French Exceptionalism Ahmet T. Kuru Islam has increasingly become an internal affair in several western European countries, ZKHUHWKH0XVOLPSRSXODWLRQKDVJURZQWRWHQWR¿IWHHQPLOOLRQ,QUHFHQW\HDUVWKH European public has intensely discussed Muslims and Islam on several occasions, from terrorist attacks in London and Madrid to the debates on Danish cartoons. In short, there is today a “Muslim question” in the minds of many European politicians when it comes to the issues of immigration, integration, and security. European states have pursued diverse policies to regulate their Muslim populations. The most controversial of these policies is France’s recent ban on wearing Muslim headscarves in public schools, which has been discussed in France and abroad since 1989. Other European countries, however, have taken Muslim students’ headscarves as a part of their individual freedom and have not prohibited them. A survey of twelve major French and British newspapers between 1989 and 1999 shows how controversial the issue was in France, in comparison to Britain. -

Religion Monitor 2008 Muslim Religiousness in Germany

Ninety percent of Muslims in Germany are religious, and 41 percent of Religion Monitor 2008 that group can even be classified as highly religious. For them, belief in God, personal prayer and attending a mosque are important aspects of Muslim Religiousness their everyday routine that have direct consequences for their lives and actions – whatever their gender, age, denomination or national origin. These are only a few of the results presented by the Bertelsmann in Germany Stiftung’s Religion Monitor. The Religion Monitor is analyzing in more depth than ever before the question of religiosity among different groups. Psychologists, religious Overview of Religious scholars, sociologists and theologians are engaged in comparing the individual levels of religiosity of a representative sample of more than Attitudes and Practices 2,000 Muslims in Germany. Their findings make an important contribution to greater understanding and dialogue between Muslims and the non- Muslim majority in German society. Religion Monitor 2008 | Muslim Religiousness in Germany Religion Monitor 2008 | Muslim Religiousness in Germany www.religionsmonitor.com Bertelsmann Stiftung Muslim Religiousness in Germany Table of Contents Editorial by Liz Mohn Muslim Religiousness by Age Group Promoting Mutual Understanding of Cultures and Religions 5 by Dr. Michael Blume 44 Overview of Muslim Religiousness in Germany What Does School Have to Do with Allah? The Most Important Results of the Religion Monitor 6 by Prof. Dr. Harry Harun Behr 50 The Religion Monitor Religiousness of Muslim Women in Germany by Dr. Martin Rieger 9 by Prof. Dr. Dr. Ina Wunn 60 Varied Forms of Muslim Religiousness in Germany Highly Religious and Diverse by Dr. -

Building Moderate Muslim Networks

THE ARTS This PDF document was made available CHILD POLICY from www.rand.org as a public service of CIVIL JUSTICE the RAND Corporation. EDUCATION ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT Jump down to document6 HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit NATIONAL SECURITY research organization providing POPULATION AND AGING PUBLIC SAFETY objective analysis and effective SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY solutions that address the challenges SUBSTANCE ABUSE facing the public and private sectors TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY around the world. TRANSPORTATION AND INFRASTRUCTURE WORKFORCE AND WORKPLACE Support RAND Purchase this document Browse Books & Publications Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore RAND Center for Middle East Public Policy View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non- commercial use only. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents. This product is part of the RAND Corporation monograph series. RAND monographs present major research findings that address the challenges facing the public and private sectors. All RAND mono- graphs undergo rigorous peer review to ensure high standards for research quality and objectivity. Building Moderate Muslim Networks Angel Rabasa Cheryl Benard Lowell H. Schwartz Peter Sickle Sponsored by the Smith Richardson Foundation CENTER FOR MIDDLE EAST PUBLIC POLICY The research described in this report was sponsored by the Smith Richardson Foundation and was conducted under the auspices of the RAND Center for Middle East Public Policy. -

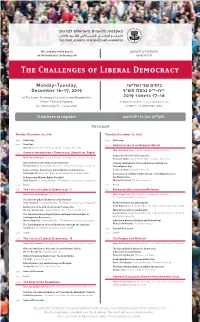

The Challenges of Liberal Democracy

אנו מתכבדים להזמינכם We cordially invite you to לכינוס בנושא an international conference on The Challenges of Liberal Democracy בימים שני ושלישי, ,Monday–Tuesday י"ח-י"ט בכסלו תש"ף December 16–17, 2019 17-16 בדצמבר at The Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities 2019 בבית האקדמיה, כיכר אלברט איינשטיין, ,Albert Einstein Square רחוב ז‘בוטינסקי 43, ירושלים Jabotinsky St., Jerusalem 43 הקליקו כאן כדי להירשם Click here to register Program Monday, December 16, 2019 Tuesday, December 17, 2019 08:30 Gathering 09:00 Gathering 09:00 Greetings 09:30 Democracies in an Unequal World Nili Cohen, President of the Academy; Tel Aviv University Chair: Benjamin Isaac, Academy Member; Tel Aviv University 09:15 General Introduction – Democracy, Liberalism, Rights Inequality in Historical Perspective Chair: Avishai Margalit, Academy Member; The Hebrew University of Jerusalem Shulamit Volkov, Academy Member; Tel Aviv University Liberal Democracy: Values and Institutions Citizens and Subjects: Voice and Representation in a Shlomo Avineri, Academy Member; The Hebrew University of Jerusalem Technological Age Representative Democracy: Vulnerabilities and Resilience Sheila Jasanoff, Harvard University Dominique Moisi, Institut Français des Relations Internationales Democracy in a Digital-Global Society: Technology Giants vs. Is Democracy Without Rights Possible? the Nation State Ruth Gavison, Academy Member; The Hebrew University of Jerusalem Michael Birnhack, Tel Aviv University 10:45 Break 11:00 Break 11:15 The Crisis of Liberal Democracy – I 11:30 Between Liberalism -

Missionaries of Africa Editor’S Word

2020 / 06 1112 MISSIONARIES OF AFRICA EDITOR’S WORD SINCE DECEMBER 1912 PETIT ECHO In this number 6 of the Petit Echo we Society of the Missionaries of Africa have asked young missionaries to give their 2020 / 06 n° 1112 opinion on what they think is a relevant ap- 10 ISSUES YEARLY PUBLISHED BY THE GENERAL COUNCIL OF THE SOCIETY proach to missionary activity in the future, Editorial Board taking into account the changes, sometimes Francis Barnes, Asst. Gen. André Simonart, Sec. Gen. disturbing and at all levels, that our world Patient Bahati is experiencing, including those caused by Freddy Kyombo Editor the Covid-19 pandemic. Freddy Kyombo [email protected] Sisters, Brothers and priests, all missio- Translations naries, lead us in their reflections and vi- Jean-Paul Guibila Steve Ofonikot sions of a better future. What approaches, Jean-Pierre Sauge what structures, what attitudes, what lan- Administrative Secretary Addresses and Dispatch guage to adopt to address the realities of this Odon Kipili time and those of tomorrow? We are all in- [email protected] vited to ask ourselves some questions about Editorial Services Guy Theunis the future we wish for ourselves, for the Dominique Arnauld Church and for the world. Correspondents Provincial/Sector Secretaries Freddy Kyombo Msola, Rome Internet Philippe Docq [email protected] Archives Photographs provided by the M.Afr Archives are subject to permission for any public use Postal Address Padri Bianchi, Via Aurelia 269, 00165 Roma, Italia Phone **39 06 3936 34211 Stampa Istituto Salesiano Pio XI Tel. 06.78.27.819 E-mail: [email protected] Cover Finito di stampare giugno 2020 The pastoral team of Kipaka, DR Congo, Robert, Hum- phrey and Romain, in their Cassava field. -

1 1Er Juin 2015 Rencontre Avec Ghaleb Bencheikh Ghaleb

1er juin 2015 Rencontre avec Ghaleb Bencheikh Ghaleb Bencheikh, né en 1960 à Djeddah en Arabie saoudite, est un docteur en sciences et physicien franco-algérien. Fils du Cheikh Abbas Bencheikh el Hocine et frère de Soheib Bencheikh, ancien recteur de la Grande Mosquée de Paris et ancien mufti de Marseille, il est également de formation philosophique et théologique et anime l'émission Islam dans le cadre des émissions religieuses diffusées sur France 2 le dimanche matin. Il préside la Conférence mondiale des religions pour la paix, ce qui l'amène à de nombreuses interventions en France et à l'étranger. Ghaleb Bencheikh propage et vulgarise à sa manière les thèses et les idées fortes de son frère Soheib Bencheikh. Il appartient au comité de parrainage de la Coordination française pour la décennie de la culture de non-violence et de paix. Bibliographie Alors, c'est quoi l'islam ?, éd. Presses de la Renaissance, 2001 L'Islam et le Judaïsme en dialogue (avec Salam Shalom et Philippe Haddad et la collaboration de Jean-Philippe Caudron), éd. de l'Atelier, 2002 La Laïcité au regard du Coran, éd. Presses de la Renaissance, 2005 Lettre ouverte aux islamistes (avec Antoine Sfeir), Bayard, 2008 A consulter aussi notamment un entretien datant de janvier 2015 : http://www.lescahiersdelislam.fr/Rencontre-avec-G-Bencheikh-et-O-Marongiu-Perria-l-islam-radical- et-la-crise-de-la-pensee-musulmane_a951.html Transcription des propos de l’orateur Je suis venu, porteur d’un sentiment d’amitié et de respect pour tous les participants de cette rencontre. Dans l’Ecclésiaste, il est dit : « il y a un temps pour tout ». -

Roger Garaudy, Abbé Pierre, and the French Negationists

Simon Epstein Roger Garaudy, Abbé Pierre, and the French Negationists The Roger Garaudy affair, was the most famous of the cases of negationism in France in the 1990s. It boosted Garaudy to the rank of chief propagator of denial of the Shoah, following in the footsteps of Paul Rassinier, who made himself known in the 1950s, and Robert Faurisson, whose hour of glory came in the 1980s. In addition, the Garaudy affair marks the point of intersection between negationism and a particularly virulent anti-Zionism. For both of these reasons—its place in the history of negationism in France and its “anti-Zionist” specificity—this affair deserves to be examined in detail, in all its phases of development. Central to such an analysis is the somewhat unusual biography of the chief protagonist. Born in 1913 to a working-class family, Roger Garaudy was first tempted by Protestantism before becoming a Marxist in 1933. A teacher of philosophy at the secondary school in Albi, in the Tarn, he became an active militant in the ranks of the French Communist Party (PCF). He was arrested in September 1940 and trans- ferred to the detention camps of the Vichy regime in Southern Algeria. Elected to the French Parliament after the war, he progressed through the Communist hierarchy and became one of the intellectuals most representative of, and loyal to the PCF. Director of the Center of Marxist Studies and Research (CERM) from 1959 to 1969, he addressed himself to promoting dialogue between Marxists and Christians. He sought to prove that Communism was compatible with humanism, in compliance with the “politics of openness” advocated by Maurice Thorez, the Communist leader. -

Zeev Sternhell

1 Prof. Zeev Sternhell From Anti-Enlightenment to Fascism and Nazism: Reflections on the Road to Genocide The purpose of this short presentation is a reflection on the road to the Holocaust and on the universal aspects of Genocide. It is a reflection on the consequences of two centuries of war against the Enlightenment, the rights of man, the idea of equality, it is a reflection on the 20th century European catastrophe and ultimately on the culture of our time. First of all let me make clear that despite the fact that the Great War is more and more commonly seen as the end of the 19th century and the matrix of the 20th century, the 20th century I am referring to came into being with the intellectual, scientific and technological revolution that preceded August 1914 by 30 years. The turn of the 20th century was one of the most fascinating and most revolutionary periods in modern history: the technological revolution, while transforming the face of the continent, greatly changed the nature of existence. From our perspective today it is important to understand how deeply the scientific revolution overturned the view men had of themselves and of the universe they inhabited. A real intellectual revolution prepared the convulsions which were soon to produce the European disaster of the first half of the 20th century. Indeed, right in the midst of a period of unprecedented scientific and technological progress, the rejection of Enlightenment's humanism, of rationalism, universalism and the idea of the rights of man reached a point of culmination and was followed by a similar rejection of the Christian vision of man.