Pacific Herring

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pacific Herring

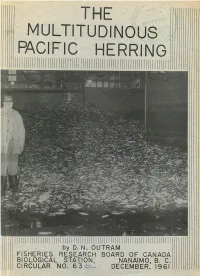

THE MULTITUDINOUS PACIFIC HERRING by D. N. OUTRAM FISHERIES RESEARCH BOARD OF CANADA BIOLOGICAL STATION, NANAIMO, B. C. CIRCULAR NO. 6 3^*u DECEMBER, 1961 COVER PHOTOGRAPH: A mountain of herring covers the storage bin area of the reduction plant at Imperial Cannery, Steveston, B„ C„, awaiting processing into fish meal and oil. Photographs by Mr. C. Morley. THE MULTITUDINOUS PACIFIC HERRING . Vast Shoals of Protein-Rich Herring Rove the Temperate Coastal Waters Along Canada's Western Seabord N V By Donald N, Outram y ^v- _•• HISTORICAL BACKGROUND annually. While this fishery is. Fabulous numbers of herring first in landed weight and second (Fig. l) are found along the sea- to salmon in landed value, it is washed shores of Canada's most wes only worth about one-quarter as much terly province, Their migrations, as the salmon catch. their sudden abundance and their Fluctuations in the world price straggle to survive is an exciting of fish meal and oil cause the market study. Undoubtedly, herring were one value at about ten million dollars to of the first coastal fishes to be vary from year to year, utilized by man. In northern Europe, FISHING FOR HERRING particularly, they have been a source The British Columbia herring of food since before written history. fishery is a highly organized opera Herring and herring roe have been an tion utilizing modern shore plants and article of food or barter of the efficient fishing vessels . The seventy- coastal Indian tribes of British Col to eighty-foot long seine boats are umbia for ma.ny centuries, They were equipped with the very latest electronic not fished, however, on a commercial fish-detecting equipment, enabling the basis until 1877 when 75 tons were fishermen to "see" the shoals before caught. -

Crappie and Crappie Fishing

Crappie & Crappie Fishing Crappie are among the most popular sport fishes in Texas. They are known by various names including white perch, sac-a-lait, calico bass, and paper-mouth. Two species are found in Texas, the white crappie (Pomoxis annularis) and black crappie (P. nigromaculatus). Black crap pie have irregular dark speck les and blotches on their sides. On white crappie, the dark markings consist of regularly arranged vertical bars. When in doubt, count the number of sharp dorsal spines at the front of a crappie’s dorsal fin. Black crappie have seven or eight spines while white crappie Young crappie feed on microscopic crustaceans called have five or six. During the spawning season, males of zooplankton. Juveniles and adults feed primarily on both species develop dark markings over most of the small threadfin and gizzard shad and insect larvae, es body, causing many anglers to misidentify male white pecially mayflies. Their diet also includes minnows, crappie as black crappie. silversides, other crappie and any other fish small enough to swallow. Black crappie are more numerous in the clear, acidic to slightly alkaline waters of East Texas. White crappie are found state In lakes with low bass populations, crappie often wide. Fish of both species may live up to eight years and overpopulate and become stunted. For crappie to reach become sexually mature at one to two years. Crappie belong larger sizes, populations must experience high total mor to the same family as the sunfishes and black basses; like tality to keep their numbers within the carrying capacity their cousins, crappie are nest builders. -

Fish Spawning Aggregations

Fish Spawning Aggregations a focal point of fisheries management and marine conservation in Mexico Photo: Octavio Aburto Authorship Brad Erisman – Coastal Fisheries Research Program, University of Texas Marine Science Institute, 750 Channel View Drive, Port Aransas, TX 78373 William Heyman – LGL Ecological Research Associates, Inc., 4103 S. Texas Avenue, Bryan TX 77802 Stuart Fulton – Comunidad y Biodiversidad, Isla del Peruano 215, Lomas de Miramar, Guaymas, Sonora, Mexico Timothy Rowell – Gulf of California Marine Program, Scripps Institution of Oceanography, 9500 Gilman Drive, La Jolla, CA 92037 Illustrations – Larry Allen and Madeline Wukusick Graphic Design – Madeline Wukusick | www.communique.design Photography – Octavio Aburto, Richard Barnden, Douglas David Seifert, Walt Stearns, Cristina Limonta, Alfredo Barroso Citation – Erisman, B., W.D. Heyman, S. Fulton, and T.Rowell 2018. Fish spawning aggregations: a focal point of fisheries management and marine conservation in Mexico. Gulf of California Marine Program, La Jolla, CA. 24 p. Email Contact: Brad Erisman, [email protected] Fish Spawning Aggregations // 2 Contents > Introduction .................................................................................................................................................................. 4 > What are fish spawning aggregations (FSAs)? ............................................................................................................ 5 > What kinds of fishes form FSAs? ................................................................................................................................ -

Important Northeast Fish Provides Bait & Forage Needs

Species Profile: Atlantic Herring Atlantic Herring Clupea harengus Important Northeast Fish Provides Bait & Forage Needs Introduction Atlantic herring (Clupea harengus) is a member of the clupeid family, which are typically small, schooling marine fishes, such as menhaden, shad, and sardines. This species is also known as sea herring because it spends its entire life cycle in the ASMFC Management Area: ME - NJ ocean (unlike the anadromous river herring). Atlantic herring inhabits the coastal Common Names: Sea herring, sar- waters of the United States from Cape Hatteras, North Carolina through Labra- dine, herring dor, Canada, and also off the coasts of Europe. Herring form the base of the food web as a forage fish for marine mammals, seabirds, and many fish throughout the Interesting Facts: * Atlantic sea herring are often Mid-Atlantic and Northeast. They are an effective and affordable bait source for confused with river herring. Sea lobster, blue crab, and tuna fishermen, and were historically sold by fish canneries herring spend their entire life at as sardines. Whale watching/ecotourism and salt retailers are indirectly dependent sea, while river herring migrate on a steady supply of herring because whales migrate inshore in pursuit of schooling annually to freshwater to spawn. * Atlantic and Pacific herring have herring and fishermen buy salt to preserve their fish. Overseas, frozen and salted been found to produce a burst herring are a valued commodity. of sound, called a Fast Repetitive Tick, at night. Its believed that The Commission’s Atlantic Herring Section manages herring in state waters (0 - 3 this high-pitched click-like sound miles from shore), while the New England Fishery Management Council (Council) is used by herring to signal their location, thereby making it easier regulates the stock in federal waters (3 - 200 miles from shore). -

Largemouth Bass Biology and Life History

SRAC Publication No. 200 August 1997 VI PR Revision Largemouth Bass Biology and Life History James T. Davis and Joe T. Lock* The largemouth bass (Micropterus Largemouth bass will eat a variety salmoides) is one of several “bass- of live fish, but bluegill are partic- es” that are actually members of ularly important in ponds and the sunfish family. There are two small lakes because they repro- recognized subspecies, the duce throughout the warm Florida and the Northern, which months. This furnishes a continual will blend genetically. Although supply of different size forage. the two subspecies differ slightly Tilapia* and/or goldfish are com- in body structure, behavior, and monly used as forage on fish growth, biochemical tests are nec- farms and in intensively managed essary to positively identify them. Largemouth bass. lakes because more can be pro- duced at lower cost. About 5 Food and growth reflex action toward anything that pounds of live forage are required moves. (The bass motto: If food is for annual maintenance, and 10 Largemouth bass are valued by there, eat it.) pounds of forage are required to fishermen chiefly because of their add 1 pound of gain to large- The availability of adequate size fighting ability. They are vora- mouth bass. cious predators that readily strike live food (baitfish or forage) usu- artificial baits. Bass begin to eat ally limits bass growth. With ade- The swimming speed of large- fish when they are about 2 inches quate forage, largemouth bass can mouth bass has not been studied long. They swallow live fish and surpass 2 pounds the first year, in depth. -

Coral Reef Fish Spawning Periodicity and Habitat in New Caledonia: a Multi-Faceted Approach in a Data-Deficient Environment

Coral Reef Fish Spawning Periodicity and Habitat in New Caledonia: a multi-faceted approach in a data-deficient environment Adrian FLYNN1*, Sébastien SARRAMEGNA2 and Michel KULBICKI3 1Hydrobiology Pty Ltd. 47 Park Rd. PO Box 2050 Milton 4064 Queensland, Australia 2 Falconbridge NC SAS, 9, rue d'Austerlitz BP MGA08 98802 Nouméa Cedex, Nouvelle-Calédonie 3 Institut de recherche pour le développment, BP A5 98848 Nouméa Cedex, Nouvelle-Calédonie *Corresponding Author: A. Flynn e-mail: [email protected] Abstract An Environmental Impact Assessment Introduction (EIA) for a proposed mining project on the west coast While most temperate fishes have a well-defined of Northern Province, New Caledonia, required an breeding season that is regulated by hormonal changes understanding of coral reef fish spawning/aggregation and a variety of environmental cues such as periodicity and habitat utilisation in New Caledonia in temperature and photoperiod (Scott 1979; Lam 1983; order to describe and mitigate the potential impacts of Bye 1984; Stacey 1984), tropical species generally the development. A study was undertaken that have a protracted breeding season and the specific encompassed literature review, interpretation of cues regulating spawning periodicity are not well oceanographic data, analysis of gonad index data known, although photoperiod, sea temperature and spanning some 18 years, analysis of commercial currents are often quoted as the most influential fisheries production data, interpretation of sales data (Munro et al. 1973; Thresher 1984; Walsh 1987). from the Nouméa fish market, interviews with Although the timing of spawning can occur commercial and subsistence fishermen and personal randomly in tropical environments, spawning is more communication with researchers at University of New commonly synchronised within a population Caledonia regarding unpublished records and (Johannes 1978; Colin and Clavijo 1988). -

Blue Water Spawning by Moorish Idols and Orangespine Surgeonfish in Palau: Is It a “Suicide Mission”?

aqua, International Journal of Ichthyology Blue Water Spawning by Moorish Idols and Orangespine Surgeonfish in Palau: Is it a “Suicide Mission”? Mandy T. Etpison1 and Patrick L. Colin2 1) Etpison Museum, PO Box 7049, Koror, Palau 96940. Email: [email protected] 2) Coral Reef Research Foundation, PO Box 1765, Koror, Palau 96940. Email: [email protected] Received: 13 December 2017 – Accepted: 05 March 2018 Keywords am Morgen zu den Laichplätzen, schlossen sich zu Gruppen Predation, aggregation, feeding frenzy, gray reef shark, zusammen und bewegten sich über der Rifffläche auf und lunar periodicity. ab und zogen dabei die Aufmerksamkeit von Beutegreifern auf sich. Um die Mittagszeit steigen sie vom Riff auf und Abstract begeben sich ins freie Wasser jenseits vom Riff. Graue Spawning aggregations of the moorish idol (MI) and or- Riffhaie folgen ihnen, greifen sie an der Oberfläche an und angespine surgeonfish (OSS) were found on the western verzehren viele von ihnen in einem Fressrausch. Ein hoher barrier reef of Palau. MI aggregated around the first quar- Prozentsatz der aufsteigenden erwachsenen HF wird von ter moon from Dec. to Mar., with largest groups in Jan. den Haien gefressen, nur wenige können in die sichere Zone and Feb. Fish arrived near the sites in the morning, des Riffs zurückkehren. KD versammeln sich in denselben grouped together and moved up and down the reef face up Monaten, aber in der Zeit des letzten Mondviertels – wobei in late morning attracting the attention of predators. At es hierüber weniger Berichte gibt. Die Beobachtungen bei mid-day they ascend from the reef out into open water beiden Fischarten, dass sie weit nach oben steigen und sich away from the reef. -

Coral Reef Fin Fish Spawning Closures Risk Assessment and Decision Support Report on Outcomes from a Workshop Held 12–13 May 2009

Queensland Primary Industries and Fisheries Coral reef fin fish spawning closures Risk assessment and decision support Report on outcomes from a workshop held 12–13 May 2009 Terry Walshe Australian Centre of Excellence for Risk Analysis University of Melbourne and Stephanie Slade Queensland Primary Industries and Fisheries Coral reef fin fish spawning closures 1 On 26 March 2009, the Department of Primary Industries and Fisheries was amalgamated with other government departments to form the Department of Employment, Economic Development and Innovation. © The State of Queensland, Department of Employment, Economic Development and Innovation, 2009. Except as permitted by the Copyright Act 1968, no part of the work may in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or any other means be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or be broadcast or transmitted without the prior written permission of the Department of Employment, Economic Development and Innovation. The information contained herein is subject to change without notice. The copyright owner shall not be liable for technical or other errors or omissions contained herein. The reader/user accepts all risks and responsibility for losses, damages, costs and other consequences resulting directly or indirectly from using this information. Enquiries about reproduction, including downloading or printing the web version, should be directed to [email protected] or telephone +61 7 3225 1398. Acknowledgments We thank all those who attended the workshop. Tracy Rout -

The Turtle and the Hare: Reef Fish Vs. Pelagic

Part 5 in a series about inshore fi sh of Hawaii. The 12-part series is a project of the Hawaii Fisheries Local Action Strategy. THE TURTLE AND THE HARE: Surgeonfi sh REEF FISH VS. PELAGIC BY SCOTT RADWAY Tuna Photo: Scott Radway Photo: Reef fi sh and pelagic fi sh live in the same ocean, but lead very different lives. Here’s a breakdown of the differences between the life cycles of the two groups. PELAGIC Pelagic Fish TOPIC Photo: Gilbert van Ryckevorsel Photo: VS. REEF • Can grow up to 30 pounds in fi rst two years • Early sexual maturity WHEN TUNA COME UPON A BIG SCHOOL OF PREY FISH, IT’S FRENETIC. “Tuna can eat up to a quarter • Periodically abundant recruitment of their body weight in one day,” says University of Hawaii professor Charles Birkeland. Feeding activity is some- • Short life times so intense a tuna’s body temperature rises above the water temperature, causing “burns” in the muscle • Live in schools tissue and lowering the market value of the fi sh. • Travel long distances Other oceanic, or pelagic, fi sh, like the skipjack and the mahimahi, feed the same way, searching the ocean for (Hawaii to Philippines) pockets of food fi sh and gorging themselves. • Rapid population turnover On a coral reef, fi sh life is very different. On a reef, it might appear that there are plenty of fi sh for eating, but it is far from the all-you-can-eat buffet Reef Fish pelagic fi sh can fi nd in schooling prey fi sh. -

Teleostei, Clupeiformes)

Old Dominion University ODU Digital Commons Biological Sciences Theses & Dissertations Biological Sciences Fall 2019 Global Conservation Status and Threat Patterns of the World’s Most Prominent Forage Fishes (Teleostei, Clupeiformes) Tiffany L. Birge Old Dominion University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/biology_etds Part of the Biodiversity Commons, Biology Commons, Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons, and the Natural Resources and Conservation Commons Recommended Citation Birge, Tiffany L.. "Global Conservation Status and Threat Patterns of the World’s Most Prominent Forage Fishes (Teleostei, Clupeiformes)" (2019). Master of Science (MS), Thesis, Biological Sciences, Old Dominion University, DOI: 10.25777/8m64-bg07 https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/biology_etds/109 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Biological Sciences at ODU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Biological Sciences Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ODU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GLOBAL CONSERVATION STATUS AND THREAT PATTERNS OF THE WORLD’S MOST PROMINENT FORAGE FISHES (TELEOSTEI, CLUPEIFORMES) by Tiffany L. Birge A.S. May 2014, Tidewater Community College B.S. May 2016, Old Dominion University A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Old Dominion University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE BIOLOGY OLD DOMINION UNIVERSITY December 2019 Approved by: Kent E. Carpenter (Advisor) Sara Maxwell (Member) Thomas Munroe (Member) ABSTRACT GLOBAL CONSERVATION STATUS AND THREAT PATTERNS OF THE WORLD’S MOST PROMINENT FORAGE FISHES (TELEOSTEI, CLUPEIFORMES) Tiffany L. Birge Old Dominion University, 2019 Advisor: Dr. Kent E. -

How to Get Channel Catfish to Spawn in a Farm Pond by Gordon Schomer, Durant State Fish Hatchery Manager

How to get Channel Catfish to Spawn in a Farm Pond By Gordon Schomer, Durant State Fish Hatchery manager Most Oklahoma fishermen have containers can be anything from old probably enjoyed fishing in one of metal milk cans or kegs, Oklahoma’s more than 250,000 earthen/ceramic chimney pipe, fiber- farm ponds. Besides bluegill or glass or plastic crocks or barrels. bass, channel catfish are one of the Even old water heaters can be used. most sought after species by farm Never use containers that have held pond anglers. Not only are channel PCB’s or other potentially harmful catfish relatively easy to catch, but chemicals. The main thing is to pick once they’re given a "cornmeal and something that both the male and hot oil bath" they can keep anglers female channel catfish can comfort- coming back time and again. Yep, ably swim into at the same time to fresh-fried catfish fillets complete spawn and be able to get back out of with hushpuppies and cole slaw is a easily. It helps to have one side of true Oklahoma delicacy. the container sealed off, allowing for For the farm pond owner, raising one way in and one way out. One channel cats can be almost as fun spawning container for every two to as catching and eating them. With five spawning pairs of fish should be just a little basic knowledge of spaced out around the perimeter of channel catfish biology, some gen- the pond in about two to five feet of eral pond management skills and a water. -

Whale Sharks Rhincodon Typus Aggregate to Feed on Fish Spawn in Belize

MARINE ECOLOGY PROGRESS SERIES Vol. 215: 275–282, 2001 Published May 31 Mar Ecol Prog Ser Whale sharks Rhincodon typus aggregate to feed on fish spawn in Belize William D. Heyman1,*, Rachel T. Graham2, Björn Kjerfve3, Robert E. Johannes4 1The Nature Conservancy, 62 Front Street, Punta Gorda, Belize 2Environment Department, University of York, c/o Box 170, Punta Gorda, Belize 3Department of Geological Sciences and Marine Science Program, University of South Carolina, Columbia, South Carolina 29208, USA 4R. E. Johannes Pty Ltd, 8 Tyndall Court, Bonnet Hill, Tasmania 7053, Australia ABSTRACT: This study confirms reports by fishermen of a large and predictable aggregation of whale sharks Rhincodon typus along the Belize Barrier Reef. Although whale sharks are rarely sighted at this location during most of the year, we counted as many as 25 whale sharks in a 50 m diameter area on 1 occasion and tagged 6 sharks during a 22 min period on another. The whale shark aggregation coincides seasonally and temporally with a multispecies reef-fish spawning aggregation at a reef promontory, Gladden Spit, at sunset, during the full and last-quarter moon periods of April and May each year. We report here, for the first time, that whale sharks feed on the freshly released spawn of cubera snappers Lutjanus cyanopterus and dog snappers L. jocu (Lutjanidae), and have documented the phenomenon with still and digital video photography of hundreds of feeding events. There is consensus locally that this remarkable interaction is in need of immediate protection from overfishing of snappers and unregulated tourism development. Our continued investigations are providing management recommendations for a new marine reserve at the site.