Mark Twain, Palestine, and American Perspectives on the Orient

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Conquest of the Promised Land: Joshua

TABLE OF CONTENTS Brief Explanation of the Technical Resources Used in the “You Can Understand the Bible” Commentary Series .............................................i Brief Definitions of Hebrew Grammatical Forms Which Impact Exegesis.............. iii Abbreviations Used in This Commentary........................................ix A Word From the Author: How This Commentary Can Help You.....................xi A Guide to Good Bible Reading: A Personal Search for Verifiable Truth ............. xiii Geographical Locations in Joshua.............................................xxi The Old Testament as History............................................... xxii OT Historiography Compared with Contemporary Near Eastern Cultures.............xxvi Genre and Interpretation: Old Testament Narrative............................. xxviii Introduction to Joshua ................................................... 1 Joshua 1.............................................................. 7 Joshua 2............................................................. 22 Joshua 3............................................................. 31 Joshua 4............................................................. 41 Joshua 5............................................................. 51 Joshua 6............................................................. 57 Joshua 7............................................................. 65 Joshua 8............................................................. 77 Joshua 9............................................................ -

Joshua Study Booklet

Old Testament Exploring the Old Testament Joshua Study Guide Fox Valley Church of Christ Joshua 1:1-24 Dig deeper With the death of Moses, the transition of responsibility is a smooth one. What is unique about this transfer, for this time in history, is that there are no challengers to Joshua’s authority and that power was not passed down to one of Moses’ sons. This stresses the fact that God is the one with the real power in Israel. Although Moses was a great leader and led the Israelites out of Egypt and back into God’s presence, It will be Joshua who will actually take them into the Day 1 promised land. We will see a similar thing in Jesus’ day when John will lead his followers in the wilderness and point the way to the goal, but it will be Jesus (whose name in Hebrew was the same as Joshua’s) who will actually accomplish 1 After the death of Moses the servant of the LORD, the LORD the final salvation of His people. said to Joshua son of Nun, Moses' aide: 2 "Moses my servant is Again, the Israelites are told that the land is theirs to take; every place they set foot dead. Now then, you and all these people, get ready to cross the is theirs, God tells them. What is unfortunate is that God had given this same Jordan River into the land I am about to give to them—to the promise many years earlier, but due to the disobedience of the Israelites, they Israelites. -

By the Same Author HOW GOD INSPIRED the BIBLE THOUGHTS

By the same Author HOW GOD INSPIRED THE BIBLE THOUGHTS FOR THE PRESENT DISQUIET HOW TO READ THE BIBLE HOW WE GOT OUR BIBLE OUR BIBLE IN THE MAKING AS SEEN BY MODERN RESEARCH THE ANCIENT DOCUMENTS AND THE MODERN BIBLE THE BIBLE FOR SCHOOL AND HOME THE BOOK OF GENESIS MOSES AND THE EXODUS JOSHUA AND THE JUDGES THE PROPHETS AND KINGS WHEN THE CHRIST CAME - THE HIGHLANDS OF GALILEE WHEN THE CHRIST CAME - THE ROAD TO JERUSALEM THE STORY OF ST. PAUL'S LIFE AND LETTERS GOD, CONSCIENCE AND THE BIBLE THE BIBLE FOR SCHOOL AND HOME BY REV. J. PATERSON SMYTH LATE PROFESSOR OF PASTORAL THEOLOGY; UNIVERSITY OF DUBLIN Author of "A People's Life of Christ," "Story of St. Paul's Life and Letters," "The Gospel of the Hereafter," "How We Got Our Bible," "How God Inspired the Bible," "How to Read the Bible," "The Ancient Documents and the Modern Bible," etc. JOSHUA AND THE JUDGES LONDON SAMPSON LOW, MARSTON & Co., LTD CONTENTS GENERAL INTRODUCTION …… v PART I: THE BOOK OF JOSHUA LESSON I THE SECRET OF COURAGE …… 29 II GOD'S POWER ………. 34 III JERICHO ……….. 38 IV ACHAN – THE DECEITFULNESS OF SIN ...44 V GIBEON ……….. 50 VI THE BATTLE OF BETH-HORON …. 54 VII CALEB – SOLDIERS OF GOD …… 61 VIII THE PLACE OF REFUGE ……. 66 IX THE STORY OF A MISUNDERSTANDING ...71 X AN OLD MAN'S ADVICE ……. 78 PART II: THE STORY OF THE JUDGES I SINNING AND PUNISHMENT, AND REPENTING AND DELIVERANCE …… 90 II FOUR DELIVERANCES ……. 95 III DEBORAH'S SONG OF PRAISE …. -

A Pilgrimage Through the Old Testament

A PILGRIMAGE THROUGH THE OLD TESTAMENT ** Year 2 of 3 ** Cold Harbor Road Church Of Christ Mechanicsville, Virginia Old Testament Curriculum TABLE OF CONTENTS Lesson 53: OLD WINESKINS/SUN STOOD STILL Joshua 8-10 .................................................................................................... 5 Lesson 54: JOSHUA CONQUERS NORTHERN CANAAN Joshua 11-15 .................................................................................................. 10 Lesson 55: DIVIDING THE LAND Joshua 16-22 .................................................................................................. 14 Lesson 56: JOSHUA’S LAST DAYS Joshua 23,24................................................................................................... 19 Lesson 57: WHEN JUDGES RULED Judges 1-3 ...................................................................................................... 23 Lesson 58: THE NORTHERN CONFLICT Judges 4,5 ...................................................................................................... 28 Lesson 59: GIDEON – MIGHTY MAN OF VALOUR Judges 6-8 ...................................................................................................... 33 Lesson 60: ABIMELECH AND JEPHTHAH Judges 9-12 .................................................................................................... 38 Lesson 61: SAMSON: GOD’S MIGHTY MAN OF STRENGTH Judges 13-16 .................................................................................................. 44 Lesson 62: LAWLESS TIMES Judges -

Ridding the Household of Insect Pests, the Witch of Endor, The

Indian State Railways VICTORIA STATION, BOMBAY Ridding the Household of Insect Pests, The Witch of Endor, The Questioning Soldier, European Children in India, Habit Formation, Hunt- ing for Sodom and Gomorrah 14-W'RLD In the opinion of Prof. W. Meinardus, of the Univer- After 122 years, during which time only Colgates have sity of Goettingen, there is enough ice piled around the directed and only Colgates have managed their perfume, antarctic regions to cover the entire surface of the world to dentifrice, and soap company, precedent has at last been a depth of more than 100 feet. Its weight is estimated at broken and the office of vice-president, director, and general twenty quadrillion tons. manager of Colgate & Co. given to Wallace E. McCaw. There was opened recently, under an arm ofSan Fran- cisco Bay, a vehicular tube wider than Holland Tunnel, The Pan-American "Peace Tree" flourishes in Havana, Cuba, where it is growing in soil brought from the twenty- 2,400 feet of It beneath the water. Instead of being bored one nations represented at the recent Pan-American Con- through the earth of rock, it was built of precast concrete in gress. Dr. Bustamente, president of the congress, mingled sections, and sunk to rest on the estuary bottom. the soil and christened the tree, which is a ceiba, with a life span of 400 years, " El Arbol de la Fraternidad Americana." The new Shakespeare Memorial Theatre at Stratford on Avon is to be built from the designs of a woman archi- tect, Miss Elizabeth Scott. The young lady, who is only What is your best day for working ? Don't say that twenty-nine years old, comes honestly by her talent for you suppose " one day is just like another; " it isn't. -

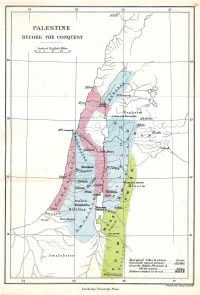

PALESTINE ' BE.FORE · ~Rhe CONQUEST

34 36 37 . \I .Arvai:v PALESTINE ' BE.FORE · ~rHE CONQUEST --·-- I Scale of L:nglisn "Miles :i.o 5 o JP 20 :,o l i 34 n-----+--- - ---------1------:--- ·----JC-.,L-~~-r-----:·-:-.,· ==",-,-c~----- ·r----7134· - I --,. I, ·- "• ,• • •• , , • - -' - - ----1----- - - - H-- I I I . ~ I' e J?·1t :a \.\ arn.aim..'0 ' \ ' .ARGOR'-·, .. ··- 33rr-----t-~--------,-----l-~ '' 33 ,1 ; • , , ' ' ' , ,-. j '--- ' , -.. ... ..... ..... -,--- -• ' --- ' 32 • 31 1t-''a\;·,~· .:;~:;: ;::;:~-:.-,-7 '--~.:-.::.-:.:-.:;.~.~-~~c:_::_ __________ 31 , ... .. .. ,", ............ _.' .... --- "... ' : ' .,, .. .. I ' II \ ' ' ., \\ ... ... • f , " \ \ ,, ,, ·,:,- ............ _ ,---· I I I ' ' ., , 11 1 'i I <. \\ ,, .. -~-·t... - -~---·- ' - ,, ,,,,, \ .. \\ ..~, .. .. --- ,j'• ,, \ ,1/ 1 I ' ,,.. \ \ ,,,, -- .. ' .... ' ,., I ,,, ,, ,,, ...... .. ,,hi ,I, I ,, \ '--... ,,,, J ' .., .. ,, ,,,, \i"\, ,, ' '\ !I ' ~ I ,, -- ,,,.,,,,. .. ' :-, ,, ,, 1, ,.,,,,, \, , I t \\ 11 ,,.,,,., ,, ,, \\ ,, 1 , - ~ I I •\ ,, ,;, \~ ,·,:-....... .. A:m a e .K i t e s .. ~~ ,,, ,, t ,, !•tl·~·-.. ~ .. (, It ~ \\ ,,,, .... ,, ,, f\ •' fl . I I \ \ •' ,, •• ,, ' I • ,',• .' .AboritJ~l ·trwes & .places.. ..... .. .. ... Oe:ar 'I 1 I t , 1 • \ •• ,.,, ,,,' ' .. _,, ~ names (proper) .................... Jeri.aw t1 ,, \ \ .........,, .... 'i: ,, ' \ .,J:, ,', .A morite-.Hittite,. Perizzitb & II r' \\ .... , , ,, ,, ~ Hi. ,, •' ,, ,,'I' "1Ylte,, ru:un.&s............ ............................... ,Jebus 'I \\ , ,, . " ,, ,, ,, I ,," ' ' ,;, ,, No.tions r~ :to .Tsraeb....... ....... -

Financing Racism and Apartheid

Financing Racism and Apartheid Jewish National Fund’s Violation of International and Domestic Law PALESTINE LAND SOCIETY August 2005 Synopsis The Jewish National Fund (JNF) is a multi-national corporation with offices in about dozen countries world-wide. It receives millions of dollars from wealthy and ordinary Jews around the world and other donors, most of which are tax-exempt contributions. JNF aim is to acquire and develop lands exclusively for the benefit of Jews residing in Israel. The fact is that JNF, in its operations in Israel, had expropriated illegally most of the land of 372 Palestinian villages which had been ethnically cleansed by Zionist forces in 1948. The owners of this land are over half the UN- registered Palestinian refugees. JNF had actively participated in the physical destruction of many villages, in evacuating these villages of their inhabitants and in military operations to conquer these villages. Today JNF controls over 2500 sq.km of Palestinian land which it leases to Jews only. It also planted 100 parks on Palestinian land. In addition, JNF has a long record of discrimination against Palestinian citizens of Israel as reported by the UN. JNF also extends its operations by proxy or directly to the Occupied Palestinian Territories in the West Bank and Gaza. All this is in clear violation of international law and particularly the Fourth Geneva Convention which forbids confiscation of property and settling the Occupiers’ citizens in occupied territories. Ethnic cleansing, expropriation of property and destruction of houses are war crimes. As well, use of tax-exempt donations in these activities violates the domestic law in many countries, where JNF is domiciled. -

The Book of JOSHUA INTRODUCTION 1

The Book of JOSHUA INTRODUCTION 1. Title. The title of the book is taken from the name of the successor of Moses, Joshua, the son of Nun, of the tribe of Ephraim. He was at first called Hoshea‘, transliterated Hoshea or Oshea (Deut. 32:44; Num. 13:8, 16), which signifies “savior” or “salvation.” According to v. 16, Moses changed his name to Yehoshua‘, Jehoshua, by prefixing the abbreviated form for Jehovah (Yahweh) to Joshua’s former name. It now signified “salvation of [or by] Jehovah.” Joshua is merely a shortened form for Jehoshua, the form always found in the Hebrew Old Testament. In the LXX he is called Iesous huios Naue, “Jesus, son of Naue [Nun].” In the New Testament he is expressly called Iesous, Jesus (Acts 7:45; Heb. 4:8). The ASV has “Joshua” in both references. Christ and the Jews recognized three divisions in the Old Testament: the Law, the Prophets, and the Psalms, or Writings (Luke 24:44). Joshua is the first book in the second division, called “the Prophets” in Hebrew Bibles, because its author occupied the office of prophet. In Hebrew Bibles the section entitled “the Prophets” is divided into two parts: the Former Prophets, comprising Joshua, Judges, Samuel, and Kings, and the Latter Prophets, comprising those we commonly know as the Prophets. Thus Joshua stands as the first book of the Prophets, although in content it is closely related to the Pentateuch, known to the Jews as the Law. 2. Authorship. Commentators and critics are divided in opinion as to whether the book was actually compiled by Joshua. -

Joshua and Judges

Introduction Gale A. Yee and Athalya Brenner This land is your land, this land is my land . I roamed and I rambled and I followed my footsteps To the sparkling sands of her diamond deserts While all around me a voice was sounding This land was made for you and me. This land is your land, this land is my land . .1 Land is central in Joshua and in Judges. It is defined as a pledged land, promised by the Hebrew God to his very own people. Much as the link between the God and his people is described as exclusive, later also as monogamist and monotheistic, so is the land. Other gods there might be; local inhabitants are acknowledged as such. But the link god-people-land excludes those inhabitants from legitimate ownership of their own land, although their actual existence is never denied. The foreignness of the Israelites, their original identity as newcomers from Mesopotamia and Egypt, is proudly stated as a token of positive otherness. Thus the land is viewed as Israelite property as well as, paradoxically, an object of collective desire; attaining tangible rather than conceptual, wishful ownership of it is reflected in the biblical text as “just” but at the same time difficult, risky, fraught with tension, and elusive. This is the story of Joshua and Judges: How the land was acquired; how groups that came to be known as Hebrews or Israelites or Judahites joined the land’s indigenous and invader inhabitants and saw it as their very own. Thus the motto for this Introduction, from the title and repeated lyrics of Woody Guthrie’s song, “This land is your land, this land is my land,” is used here ironically. -

Bible-Lands-Travel-Guide-2019.Pdf

Contents Maps ..............................................................1 Index ..............................................................4 Quick Reference Guide for Biblical Sites and Places .................................9 Song Lyrics ....................................................45 Daily Devotions .......................................... 109 2019 Itinerary & Travelers .......................... 123 © Berkshire Institute for Christian Studies PO Box 1888 | Lenox, MA 01240 | 413-637-4673 www.berkshireinstitute.org This resource has been compiled solely for educational use in conjunction with the BICS Bible Lands Seminar, and may not be sold or distributed for any other purpose. Cover photo by Joe Hession, used by permission. Berkshire Institute for Christian Studies o 2 o Bible Lands Travel Guide Jerusalem - the Old City o 3 o Berkshire Institute for Christian Studies Index of Biblical Sites and Places Acacia Tree (Arad) .................................................................................26 Almond Tree (Tel Dan) ...........................................................................18 Arad .......................................................................................................25 Azekah (Valley of Elah) ..........................................................................36 Bedouin Tents (Arad) .............................................................................26 Bethany .................................................................................................38 Bethlehem -

Wholehearted- the Book of Joshua

Field Manual Wholehearted- The Book of Joshua By Teaching Pastor, Andy Savage INTRODUCTION Something does not make sense to me… the God of the universe has clearly given us His purposes with the promise of great bless- ing, yet we are so often half-hearted in our pursuit of those purposes. This study is designed to get to the heart of wholehearted pursuit of God’s purposes. Are you wholehearted in your commitment to the purposes of God? I believe the life story of Joshua and specifically his leadership of the Israelites into the Promised Land is a case study in wholehearted commitment to God’s purposes. This “field manual” gives you the opportunity to study the entire book of Joshua in a way that helps you marry whole- hearted commitment with the clear, Biblical purposes of God. I think we can all admit that it is our tendency is to limit the work of God in our lives either by our half-hearted commitment to His purposes or by abandoning His purposes all together. Make no mistake - pursuing God’s purposes is no small task. Right now there are many things that exist in your life that keep you from the brave pursuit of God’s purposes. Over the next 21 days you will face the fear and discouragement in your faith and discover areas of your life that needs changing or thrown away. Joshua is one of the great men of God in scripture. God used him in a mighty way to literally deliver the Prom- ised Land to the Jewish nation. -

CANAAN W Ldbrness

J4 35 37 CANAAN Iii THC TIM£: OF THE PATRl,.A.CH$ _Ufuslrrd,,;fd;ePenb¥r,mclr. F"(/lw-l.Hii'e, J4 .., Q:; W ldbrness o, .s'h~r j i J4- 36 JJ .JO-NN HtYWOOD, UTliQ, MAN-Cff[.$Tl"R • L-ONOON. ANALYSIS OF THE BOOK OF JOSHUA WITH NOTES CRITICAL, HISTORICAL, AND GEOGRAPHICAL ; ALSO MAPS AND EXAMINATION QUESTIONS. BY LEWIS HUGHES, B.A., CORPUS CHRISTI COL.LEGE, CAMBRIDGE, (FORMERLY ONE OF '.fHE PRINCIPALS OF THE :BOLTON HIGH SCHOOL FOR BOYS), AND REv. T. BOSTON JOHNSTONE, ST. ANDREW'S UNIVERSITY, Authors of "Analysis of the Books of Jeremiah, Ezra, Nehemiah," &c. CHIEFLY INTENDED FOR CANDIDATES PREPARING FOR THE OXFORD AND C.!MilRIDGE LOCAL, AND THE COLLEGE OF PRECEPTORS' EXAMINATIONS. JOHN HEYWOOD, . DEANSGATE A?--'D RIDGEFIELD, MANCHESTER ; AND 11 1 PATERNOSTER BUILDINGS; LONDON. 1884. PREFACE. IN studying Scripture History, a great difficulty· is often experienced by young students, in not being able to lave- a, simJlll.e• a.nd- con nected view of the whole narrative, before oo,1Jerihg u !lllln the minute details. Being well aware of the existooee- of thiii diilfulu.l.ty, we have endeavoured to give the student, m a sim])l.e manner,. such a view of the period of history, contained illl tllie Book li>f. J;oshu.a,, ai, will make the study interesting. The plan of study we reco=end is -no .ead the l:lllJTll.tive por .. tion of this Analysis first, and after this is done, to take the Bibi~ and study the book, chapter by chapter, with the aid .,f the Notes, &c., as contained in the second portion 0f the Analysis.