Savings and Retail Banking in Africa a Case Study on Innovative Business Models: Partnerships As a Key to Unlocking the Mass Market May 2021 Table of Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Peter Mapigano

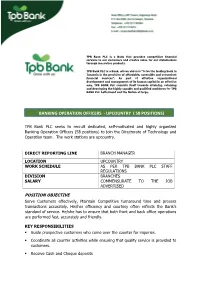

TPB Bank PLC is a Bank that provides competitive financial services to our customers and creates value for our stakeholders through innovative products. TPB Bank PLC is a Bank, whose vision is “to be the leading bank in Tanzania in the provision of affordable, accessible and convenient financial services”. As part of effective organizational development and management of its human capital in an effective way, TPB BANK PLC commits itself towards attaining, retaining and developing the highly capable and qualified workforce for TPB BANK PLC betterment and the Nation at large. BANKING OPERATION OFFICERS - UPCOUNTRY ( 58 POSITIONS) TPB Bank PLC seeks to recruit dedicated, self-motivated and highly organized Banking Operation Officers (58 positions) to join the Directorate of Technology and Operation team. The work stations are upcountry . DIRECT REPORTING LINE BRANCH MANAGER LOCATION UPCOUNTRY WORK SCHEDULE AS PER TPB BANK PLC STAFF REGULATIONS DIVISION BRANCHES SALARY COMMENSURATE TO THE JOB ADVERTISED POSITION OBJECTIVE Serve Customers effectively, Maintain Competitive turnaround time and process transactions accurately. His/her efficiency and courtesy often reflects the Bank’s standard of service. He/she has to ensure that both front and back office operations are performed fast, accurately and friendly. KEY RESPONSIBILITIES . Guide prospective customers who come over the counter for inquiries. Coordinate all counter activities while ensuring that quality service is provided to customers. Receive Cash and Cheque deposits . Posting Transactions . Verify teller proof of cash and teller proof of cheques against actual documents by ticking and signing the printouts. Scrutinize internal vouchers to ensure that they are properly drawn and authorized in line with the approval limits. -

Tanzania Mortgage Market Update – 31 December 2020

TANZANIA MORTGAGE MARKET UPDATE – 31 DECEMBER 2020 1. Highlights The mortgage market in Tanzania registered a 6 percent annual growth in the value of mortgage loans from 31 December 2019 to 31 December 2020. On a quarter to quarter basis; the mortgage market in Tanzania registered a 4 percent growth in the value of mortgage loans as at 31 December 2020 compared to previous quarter which ended on 30 September 2020. There was no new entrant into the mortgage market during the quarter. The number of banks reporting to have mortgage portfolios increased from 31 banks to 32 banks recorded in Q4 2020 due to reporting to BOT by Mwanga Hakika Bank the newly formed bank after merger of Mwanga Community Bank, Hakika Microfinance Bank and EFC Microfinance Bank. EFC Microfinance bank did not report in Q3-2020 due to revocation of their licence after the merger and the newly formed bank reported for the first time in Q4-2020. Outstanding mortgage debt as at 31 December 2020 stood at TZS 464.14billion1 equivalent to US$ 200.93 million compared to TZS 445.21 billion equivalent to US$ 192.81 as at 30 September 2020. Average mortgage debt size was TZS 78.56 million equivalent to US$ 34,010 (TZS 76.67 million [US$ 33,203] as at 30 September 2020). The ratio of outstanding mortgage debt to Gross Domestic Product (GDP) increased to 0.30 percent compared to 0.28 percent recorded for the quarter ending 30 September 2020. Mortgage debt advanced by top 5 Primary Mortgage Lenders (PMLs) remained at 69 percent of the total outstanding mortgage debt as recorded in the previous quarter. -

Implications of the Covid-19 Pandemic on the Banking Industry and the Role That Mergers and Acquisitions May Play

IMPLICATIONS OF THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC ON THE BANKING INDUSTRY AND THE ROLE THAT MERGERS AND ACQUISITIONS MAY PLAY TANZANIA POSTAL BANK PLC & TIB CORPORATE BANK LIMITED 1 TPB BANK PLC‘S MERGER WITH TIB CORPORATE BANK LIMITED AND ITS IMPLICATIONS ON THE BANKING INDUSTRY AMID COVID-19 The recent announcement of TPB Bank Plc’s (“TPB”) merger with TIB Corporate Bank Limited (“TIB’) was met with much optimism especially within the Tanzanian banking and media industry. This is owed to the fact that TPB has now joined a unique group of commercial banks operating in Tanzania that hold assets amounting to TZS 1 trillion (approximately USD 431 million) or more. This follows the government owned lender’s acquisition of the assets and liabilities of TIB, which is also a government majority owned bank. This signals a continued shift towards consolidation within the banking industry but also further raises questions of the implications of the COVID-19 pandemic on the banking industry and the role that mergers and acquisitions may play in its consequences. The evidentiary shift to mergers within the banking industry is highlighted by the fact that TPB on its own has been party to three mergers within the past two years in which Twiga Bancorp Limited (“Twiga Bancorp”), the Tanzania Women’s Bank and now TIB have all been subsumed under its control. One of the main reasons cited for the merger between TPB and TIB has been the need to increase efficiency and reduce operational costs. However, the standout issue appears to be the fact that TIB had one of the highest levels of nonperforming loans in the market potentially leading to expensive and drawn out litigation in recovering said loans. -

MKUTANO WA KUMI NA TISA Kikao Cha Arobaini Na Sita

NAKALA MTANDAO(ONLINE DOCUMENT) BUNGE LA TANZANIA ________ MAJADILIANO YA BUNGE _________ MKUTANO WA KUMI NA TISA Kikao cha Arobaini na Sita – Tarehe 15 Juni, 2020 (Bunge Lilianza Saa Tatu Asubuhi) D U A Spika (Mhe. Job Y. Ndugai) Alisoma Dua SPIKA: Waheshimiwa Wabunge tukae, tunaendelea na Mkutano wetu wa 19, Kikao cha 46, bado kimoja tu cha kesho. Katibu! NDG. STEPHEN KAGAIGAI – KATIBU WA BUNGE: HATI ZILIZOWASILISHWA MEZANI Hati zifuatazo ziliwasilishwa mezani na: NAIBU WAZIRI WA FEDHA NA MIPANGO: Maelezo ya Waziri wa Fedha na Mipango kuhusu Muswada wa Sheria ya Fedha wa Mwaka 2020 (The Finance Bill, 2020). Muhtasari wa Tamko la Sera ya Fedha kwa Mwaka wa Fedha 2020/2021 (Monetary Policy Statement for the Financial Year 2020/2021). MHE. ALBERT N. OBAMA - K.n.y. MWENYEKITI WA KAMATI YA KUDUMU YA BUNGE YA BAJETI:Maoni ya Kamati ya Kudumu ya Bunge ya Bajeti Kuhusu Muswada wa Sheria ya Fedha wa Mwaka 2020 (The Finance Bill, 2020). 1 NAKALA MTANDAO(ONLINE DOCUMENT) MHE. RHODA E. KUNCHELA - K.n.y. MSEMAJI MKUU WA KAMBI RASMI YA UPINZANI BUNGENI KWA WIZARA YA FEDHA NA MIPANGO: Maoni ya Kambi Rasmi ya Upinzani Bungeni kuhusu Muswada wa Sheria ya fedha wa mwaka 2020 (The Finance Bill, 2020). MHE. DKT. TULIA ACKSON - MAKAMU MWENYEKITI WA KAMATI YA KUDUMU YA BUNGE YA KANUNI ZA BUNGE: Azimio la Kamati ya Kudumu ya Bunge ya Kanuni za Bunge kuhusu Marekebisho ya Kanuni za Bunge SPIKA: Asante sana Mheshimiwa Naibu Spika, Katibu MASWALI NA MAJIBU (Maswali yafuatayo yameulizwa na kujibiwa kwa njia ya mtandao) Na. 426 Migogoro ya Mipaka MHE. -

Peter Mapigano

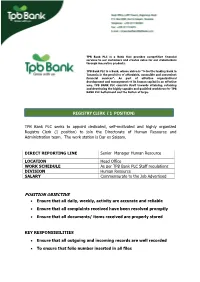

TPB Bank PLC is a Bank that provides competitive financial services to our customers and creates value for our stakeholders through innovative products. TPB Bank PLC is a Bank, whose vision is “to be the leading bank in Tanzania in the provision of affordable, accessible and convenient financial services”. As part of effective organizational development and management of its human capital in an effective way, TPB BANK PLC commits itself towards attaining, retaining and developing the highly capable and qualified workforce for TPB BANK PLC betterment and the Nation at large. REGISTRY CLERK ( 1 POSITION) TPB Bank PLC seeks to appoint dedicated, self-motivated and highly organized Registry Clerk (1 position) to join the Directorate of Human Resource and Administration team. The work station is Dar es Salaam. DIRECT REPORTING LINE Senior Manager Human Resource LOCATION Head Office WORK SCHEDULE As per TPB Bank PLC Staff regulations DIVISION Human Resource SALARY Commensurate to the Job Advertised POSITION OBJECTIVE Ensure that all daily, weekly, activity are accurate and reliable Ensure that all complaints received have been resolved promptly Ensure that all documents/ items received are properly stored KEY RESPONSIBILITIES Ensure that all outgoing and incoming records are well recorded To ensure that folio number inserted in all files Dispatching of documents to different departments Custodian of post office keys To dispatching incoming mail or parcels from post office to officers Duplicating, reproducing, collecting and stapling materials of various natures as may be directed by supervisor. Robust management of all records archives. Ensure that at all times documents are neatly arranged on racks and properly labelled. -

The United Republic of Tanzania National Audit Office

THE UNITED REPUBLIC OF TANZANIA NATIONAL AUDIT OFFICE Vision To be a highly regarded institution that excels in public sector auditing Mission To provide high quality audit services that improve public sector performance, accountability and transparency in the management of public resources Core Values In providing quality service, National Audit Office of Tanzania shall be guided by the following Core Values: Objectivity To be an impartial entity, that offers services to our clients in an unbiased manner We aim to have our own resources in order to maintain our independence and fair status Excellence We are striving to produce high quality audit services based on best practices Integrity To be a corrupt free organization that will observe and maintain high standards of ethical behavior and the rule of law Peoples’ Focus We focus on our stakeholders needs by building a culture of good customer care, and having a competent and motivated workforce Innovation To be a creative organization that constantly promotes a culture of developing and accepting new ideas from inside and outside the organization Best Resource Utilization To be an organization that values and uses public resources entrusted to us in an efficient, economic and effective manner i PREFACE The Public Audit Act No. 11 of 2008, Section 28, authorizes the Controller and Auditor General to carry out Performance Audit (Value for-Money Audit) for the purpose of establishing economy, efficiency and effectiveness of any expenditure or use of resources in the Ministries, Departments and Agencies (MDAs), Local Government Authorities (LGAs) and Public Authorities and other Bodies. The Performance Audit involves enquiring, examining, investigating and reporting on the use of public resources, as deemed necessary under the prevailing circumstances. -

Annual Report 2019/20 Bank of Tanzania

BANK OF TANZANIA - ANNUAL REPORT 2019/20 REPORT ANNUAL - TANZANIA BANK OF BANK OF TANZANIA ANNUAL REPORT For inquiries contact: Director of Economic Research and Policy Bank of Tanzania, 2 Mirambo Street 11884 Dar es Salaam 2019/20 Tel: +255 22 223 3328/9 http://www.bot.go.tz BANK OF TANZANIA ANNUAL REPORT 2019/20 Bank of Tanzania Annual Report 2019/20 © Bank of Tanzania. All rights reserved. This report is intended for general information only and is not intended to serve as financial or any other advice. No content of this publication may be quoted or reproduced in any form without fully acknowledging the Bank of Tanzania Annual Report as the source. The Bank of Tanzania has taken every precaution to ensure accuracy of information, however, shall not be liable to any person for inaccurate information or opinion contained in this publication. For any inquiry please contact: Director of Economic Research and Policy Bank of Tanzania, 2 Mirambo Street 11884, Dar es Salaam Telephone: +255 22 223 3328/9 Email: [email protected] This report is also available at: http://www.bot.go.tz ISSN 0067-3757 B Bank of Tanzania Annual Report 2019/20 December 2020 Hon. Dr. Philip I. Mpango (MP) Minister of Finance and Planning United Republic of Tanzania Government City – Mtumba Hazina Street P.O. Box 2802 40468 Dodoma TANZANIA Honourable Minister, LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL In accordance with Section 21 (1) of the Bank of Tanzania Act, 2006 Cap. 197 as amended, I hereby submit: a) The report on economic developments and the Bank of Tanzania’s operations, in particular, the implementation and outcome of monetary policy, and other activities during the fiscal year 2019/20; and b) The Bank of Tanzania Balance Sheet, the Profit and Loss Accounts and associated financial statements for the year ended 30th June 2020, together with detailed notes to the accounts for the year and the previous year’s comparative data certified by external auditors along with the auditors’ opinion. -

Download This PDF File

Financial Development and Private Sector Investment in the Post-Financial Liberalization Era in Tanzania Francis LWESYA1, Ismail J. ISMAIL2 1 University of Dodoma, PO. BOX 1208, Dodoma, TZ; [email protected] (corresponding author) 2 University of Dodoma, PO. BOX 1208, Dodoma, TZ; [email protected] Abstract: This paper examines the relationship between financial development and private sector investment in the post-financial sector liberalization episode in Tanzania. The proxies for financial development were the financial market depth index and financial institutions depth index. Applying Autoregressive Distributed Lag (ARDL) technique, the results show the nexus between financial development and private sector investment in Tanzania. We find that the financial market depth index has a positive and significant impact on private sector investment in the long run but not in the short run. This is linked to the underdevelopment of capital markets in Tanzania at present. Similarly, we find that the financial institution depth index positively and significantly impacts private sector investment in both the long and short run. The degree of openness of the economy recorded a positive and significant impact on private investment in both periods suggesting that it has played a critical role in the financial development and growth of the private sector in Tanzania. In contrast, we observe that the real exchange rate has recorded a negative and significant impact on private investment in the long and short run. This suggests that appreciation of the real exchange rate had a negative impact on private investment. We recommend increasing financial openness and reinforcing the financial regulatory reforms to widen and deepen the financial system that can effectively support the mobilization of short, medium, and long-term finance for private sector investment. -

Phase One of SGR Project Almost Done, Government Says

ISSN: 1821 - 6021 Vol XIII - No. 09 • Tuesday . March 3, 2020 JKT wins praise for meeting value for money objectives DID YOU By TPJ Reporter, Dodoma KNOW? NATIONAL Services-JKT has won Bidders can now access accolades from the Chief of Defence Forces, General Venance Mabeyo, bid documents and for complying with the procurement participate in electron- law and ensuring attainment of ic tendering processes value for money in various projects through Taneps at the they have undertaken across the country. comfort of their offic- During the commissioning of the newly constructed es. headquarters of the National Services-JKT at Buigiri in NEWS? IN Chamwino District, in Dodoma recently, General Mabeyo praised JKT’s steadfastness in Chief of Defence Forces, General Venance Mabeyo Numbers implementing projects in a timely manner while sticking to laid out procedures thereby meeting value Gen. Mabeyo said that JKT standards in implementation 531 for money objectives. -implemented projects have been of projects and to adhere to Number of Annual exemplary and went on to cite procurement law and government “You must now enhance your fences at Mirerani, Chamwino procedures at all times. Procurement Plans (APPs) capacity and acquire your own State House and Ngerengere state -of -the art equipment to Furthermore, Gen Mabeyo for financial year 2019/20 airstrip as well as the Prisons urged JKT to take good care of enable you implement even more Department’s Ukonga houses submitted by Procuring major construction projects in the the new headquarters to ensure in Dar es Salaam, and called they last long. Entities through Taneps country,” said Gen. -

MAJADILIANO YA BUNGE MKUTANO WA KUMI NA TISA Kikao Cha Thelathini Na Sita

NAKALA MTANDAO(ONLINE DOCUMENT) BUNGE LA TANZANIA _________ MAJADILIANO YA BUNGE _______________ MKUTANO WA KUMI NA TISA Kikao cha Thelathini na Sita – Tarehe 26 Mei, 2020 (Bunge Lilianza Saa Nane Kamili Mchana) D U A Spika (Mhe. Job Y. Ndugai) Alisoma Dua SPIKA: Waheshimiwa Wabunge, naomba tukae. Waheshimiwa Wabunge tunaendelea na Mkutano wetu wa mwisho, Mkutano wa Kumi na Tisa, Kikao cha leo ni cha Thelathini na Sita. MASWALI NA MAJIBU (Maswali yafuatayo yameulizwa na kujibiwa kwa njia ya mtandao) Na. 336 Kudhibiti Ufanyaji Biashara Holela Nchini MHE. ASHA ABDULLAH JUMA aliuliza:- Zoezi la kuwapatia vitambulisho wajasiriamali wamachinga limefanyika vizuri na kuendelea kufanya biashara zao mahali popote. Je, Serikali imejipanga vipi ili kuhakikisha kuwa na usimamizi na udhibiti katika ufanyaji wa biashara holela? 1 NAKALA MTANDAO(ONLINE DOCUMENT) WAZIRI WA NCHI, OFISI YA RAIS, TAWALA ZA MIKOA NA SERIKALI ZA MITAA alijibu:- Mheshimiwa Spika, kwa niaba ya Waziri wa Nchi, Ofisi ya Rais, Tawala za Mikoa na Serikali za Mitaa, naomba kujibu swali la Mheshimiwa Asha Abdallah Juma, Mbunge wa Viti Maalum kama ifuatavyo:- Mheshimiwa Spika, Serikali kupitia Wizara ya Fedha na Mipango kwa kushirikiana na Ofisi ya Rais, Tawala za Mikoa na Serikali za Mitaa, imetunga Kanuni za Usimamizi wa Kodi (Usajili wa Wafanyabiashara Wadogo na Watoa Huduma) za mwaka 2020. Kwa mujibu wa Kanuni hizo, Mamlaka za Serikali za Mitaa zimeelekezwa kusimamia na kutenga maeneo kwa ajili ya wafanyabiashara na watoa huduma Wadogo ili kuhakikisha biashara holela zinadhibitiwa. Udhibiti na usimamizi utafanyika wakati wa kusajili na kuwapatia vitambulisho wajasiriamali wadogo kwa lengo la kuwawezesha kiuchumi na kuhakikisha wanaendesha shughuli zao pasipo kubugudhiwa. -

EAC Financial Inclusion Stakeholder Mapping

EAC Financial Inclusion Stakeholder Mapping REPORT JANUARY - 2020 Supported by the: 1 Acknowledgements This report was produced by FinTechStage and Canela Consulting (our research partners). Contributors included Dr. Erin Taylor, Dr. Whitney Easton and Luis Carlos Serna Prati. Ariadne Plaitakis contributed material on regulation. Data analysis was carried out by Mariela Atannasova and Gawain Lynch. Infographics were produced by Ana Subtil, Mariela Atanassova and Whitney Easton. We would like to thank the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation for their active support of the programme and the broad access to research material on Financial Inclusion. Lazaro Campos Co-Founder, FinTechStage January 2020 2 EAC FINANCIAL INCLUSION STAKEHOLDER MAPPING - REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The East African Community (EAC), a regional economic community, is often presented as a model of financial inclusion in Africa. Over the past few years, we have seen tremendous improvement across the region, but much remains to be done. The purpose of this body of work is to understand the state of financial inclusion across the EAC and identify how to advance. The first step is to map the financial inclusion landscape to identify stakeholders, gaps, and areas for intervention. We carried out data collection and network mapping for all six EAC Member States. In this report we identify: • All stakeholders who are working on financial inclusion issues in the EAC, including the financial sector, mobile network operators (MNOs), mobile money operators (MMOs), microfinance institutions -

Government Sees Infrastructural Projects As Kingpins of Economy

ISSN: 1821–6021 Vol XIII–No. 14 Tuesday April 7, 2020 Government sees infrastructural projects as kingpins of economy By TPJ Reporter, Dodoma DID YOU THE Government sees implemention of flagship KNOW? infrastructural projects as key in its bid to transform the economy and livehhoods of Tanzanians, Parliament Bidders can now was told in Dodoma recently. This was the gist of Prime Minister Kassim Maja- access bid documents liwa’s speech in Parliament recently when he pre- and participate in sented the budget estimates for Prime Minister’s electronic tendering Office for Financial Year 2020/21. processes through The prime minister told Parliament that in order to attain the national development plan targets, the Taneps conviniently in Government would especially ensure smooth imple- their offices. mentation of three flagship projects namely Standard PRIME Minister Kassim Majaliwa Gauge Railway, Julius Nyerere Hydroelectric Power He said phase one of the SGR project from Dar es and the crude oil pipeline from Hoima in Uganda NEWS? IN Salaam to Morogoro, on which the Government had to Tanga. Numbers until March, 2020 spent TZS 2.96 trilion has been a “The Government is determined to linkup con- good source of employment and tender opportunites struction of enabling infrastructure and other sectors for Tanzanians. of the economy in order to enhance economic devel- 529 “Upon completion, the project will enhance effi- Number of Annual opment, employment opportunities and revenue col- ciency in transportation of people and goods, will Procurement Plans (APPs) lection,” said Mr. Majaliwa. for financial year 2019/20 Continued on Page 2 that have been approved and published at www.