Converging Information and Communication Systems the Case of Television and Computers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FCC-06-11A1.Pdf

Federal Communications Commission FCC 06-11 Before the FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION WASHINGTON, D.C. 20554 In the Matter of ) ) Annual Assessment of the Status of Competition ) MB Docket No. 05-255 in the Market for the Delivery of Video ) Programming ) TWELFTH ANNUAL REPORT Adopted: February 10, 2006 Released: March 3, 2006 Comment Date: April 3, 2006 Reply Comment Date: April 18, 2006 By the Commission: Chairman Martin, Commissioners Copps, Adelstein, and Tate issuing separate statements. TABLE OF CONTENTS Heading Paragraph # I. INTRODUCTION.................................................................................................................................. 1 A. Scope of this Report......................................................................................................................... 2 B. Summary.......................................................................................................................................... 4 1. The Current State of Competition: 2005 ................................................................................... 4 2. General Findings ....................................................................................................................... 6 3. Specific Findings....................................................................................................................... 8 II. COMPETITORS IN THE MARKET FOR THE DELIVERY OF VIDEO PROGRAMMING ......... 27 A. Cable Television Service .............................................................................................................. -

The Crisis of Contemporary Arab Television

UC Santa Barbara Global Societies Journal Title The Crisis of Contemporary Arab Television: Has the Move towards Transnationalism and Privatization in Arab Television Affected Democratization and Social Development in the Arab World? Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/13s698mx Journal Global Societies Journal, 1(1) Author Elouardaoui, Ouidyane Publication Date 2013 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California The Crisis of Contemporary Arab Television | 100 The Crisis of Contemporary Arab Television: Has the Move towards Transnationalism and Privatization in Arab Television Affected Democratization and Social Development in the Arab World? By: Ouidyane Elouardaoui ABSTRACT Arab media has experienced a radical shift starting in the 1990s with the emergence of a wide range of private satellite TV channels. These new TV channels, such as MBC (Middle East Broadcasting Center) and Aljazeera have rapidly become the leading Arab channels in the realms of entertainment and news broadcasting. These transnational channels are believed by many scholars to have challenged the traditional approach of their government–owned counterparts. Alternatively, other scholars argue that despite the easy flow of capital and images in present Arab television, having access to trustworthy information still poses a challenge due to the governments’ grip on the production and distribution of visual media. This paper brings together these contrasting perspectives, arguing that despite the unifying role of satellite Arab TV channels, in which national challenges are cast as common regional worries, democratization and social development have suffered. One primary factor is the presence of relationships forged between television broadcasters with influential government figures nationally and regionally within the Arab world. -

Privalomo Skaitmeninės Televizijos Retransliavimo Elektroninių Ryšių Tinklais Teisinis Reguliavimas

MYKOLO ROMERIO UNIVERSITETAS SOCIALINĖS INFORMATIKOS FAKULTETAS ELEKTRONINIO VERSLO KATEDRA DONATAS VITKUS Naujųjų technologijų teisė, NTTmns0-01 PRIVALOMO SKAITMENINĖS TELEVIZIJOS RETRANSLIAVIMO ELEKTRONINIŲ RYŠIŲ TINKLAIS TEISINIS REGULIAVIMAS Magistro baigiamasis darbas Darbo vadovas – Doc. dr. Darius Štitilis Vilnius, 2011 TURINYS ĮVADAS .............................................................................................................................................. 3 1 PRIVALOMO TELEVIZIJOS RETRANSLIAVIMO INSTITUTAS IR JO SVARBA ... 9 1.1 Televizijos techniniai aspektai ir rūšys ........................................................................ 9 1.2 Retransliavimo sąvokos identifikavimas .................................................................... 13 1.3 Privalomas paketas ir jo reikšmė ................................................................................ 15 2 PRIVALOMO SKAITMENINĖS TELEVIZIJOS RETRANSLIAVIMO TEISINIS REGULIAVIMAS ES ŠALYSE ..................................................................................................... 19 2.1 Bendrasis „must carry“ reguliavimas ES ................................................................... 19 2.2 Austrija ....................................................................................................................... 21 2.3 Vokietija ..................................................................................................................... 22 2.4 Jungtinė Karalystė ..................................................................................................... -

Colossus Record High Definition Video to Your PC!

Colossus Record High Definition video to your PC! Record your Xbox®360 and PlayStation®3 video game play in HD. Share your best games with your friends*! Record TV programs in HD from cable & satellite set top boxes using high quality H.264 Burn your HD recordings to Blu-ray compatible DVD discs Technical Specifications System Requirements • Hardware encoder: • PC with 3.0 GHz single core or 2.0 GHz multi-core processor (or – H.264 AVCHD high definition video encoder faster) – Multi-channel audio (2 or 5.1 channel audio) from optical • Microsoft® Windows® 7 (32 or 64-bit), Windows Vista or audio or HDMI input, or two channel stereo audio Windows XP Service Pack 3 – Recording datarate: • 512 MB RAM (1 GB recommended) from 1 to 20 Mbits/sec • Graphics card with 256 MB memory – Recording formats: • Sound card AVCHD (.TS and .M2TS) and .MP4 • 220 MB free hard disk space Resolution up to 1080i from component (YCrCb and YPrPb) • CD-ROM drive (for Software installation) and HDMI video The video input format determines the recorded format. For Bundled software applications example, 1080i input records at 1080i, 720p records at 720p, • Arcsoft TotalMediaExtreme: for video capture, preview, playback, etc. Hauppauge’s WinTV v7 application, to schedule the recording of • Input/output connections your TV and other video programs. – HDMI input, from non-encrypted HDMI sources such as the • ArcSoft ShowBiz, with these features: Xbox 360 and D-SLR cameras – Video capture for recording video game play Note: Colossus will not record video from HDMI sources with – Authoring, trimming and burning your video recordings onto a HDCP copy protection. -

Henry Jenkins Convergence Culture Where Old and New Media

Henry Jenkins Convergence Culture Where Old and New Media Collide n New York University Press • NewYork and London Skenovano pro studijni ucely NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS New York and London www.nyupress. org © 2006 by New York University All rights reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Jenkins, Henry, 1958- Convergence culture : where old and new media collide / Henry Jenkins, p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-8147-4281-5 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-8147-4281-5 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Mass media and culture—United States. 2. Popular culture—United States. I. Title. P94.65.U6J46 2006 302.230973—dc22 2006007358 New York University Press books are printed on acid-free paper, and their binding materials are chosen for strength and durability. Manufactured in the United States of America c 15 14 13 12 11 p 10 987654321 Skenovano pro studijni ucely Contents Acknowledgments vii Introduction: "Worship at the Altar of Convergence": A New Paradigm for Understanding Media Change 1 1 Spoiling Survivor: The Anatomy of a Knowledge Community 25 2 Buying into American Idol: How We are Being Sold on Reality TV 59 3 Searching for the Origami Unicorn: The Matrix and Transmedia Storytelling 93 4 Quentin Tarantino's Star Wars? Grassroots Creativity Meets the Media Industry 131 5 Why Heather Can Write: Media Literacy and the Harry Potter Wars 169 6 Photoshop for Democracy: The New Relationship between Politics and Popular Culture 206 Conclusion: Democratizing Television? The Politics of Participation 240 Notes 261 Glossary 279 Index 295 About the Author 308 V Skenovano pro studijni ucely Acknowledgments Writing this book has been an epic journey, helped along by many hands. -

UNIVERSIDAD AUTÓNOMA DE CIUDAD JUÁREZ Instituto De Ingeniería Y Tecnología Departamento De Ingeniería Eléctrica Y Computación

UNIVERSIDAD AUTÓNOMA DE CIUDAD JUÁREZ Instituto de Ingeniería y Tecnología Departamento de Ingeniería Eléctrica y Computación GRABADOR DE VIDEO DIGITAL UTILIZANDO UN CLUSTER CON TECNOLOGÍA RASPBERRY PI Reporte Técnico de Investigación presentado por: Fernando Israel Cervantes Ramírez. Matrícula: 98666 Requisito para la obtención del título de INGENIERO EN SISTEMAS COMPUTACIONALES Profesor Responsable: M.C. Fernando Estrada Saldaña Mayo de 2015 ii Declaraci6n de Originalidad Yo Fernando Israel Cervantes Ramirez declaro que el material contenido en esta publicaci6n fue generado con la revisi6n de los documentos que se mencionan en la secci6n de Referencias y que el Programa de C6mputo (Software) desarrollado es original y no ha sido copiado de ninguna otra fuente, ni ha sido usado para obtener otro tftulo o reconocimiento en otra Instituci6n de Educaci6n Superior. Nombre alumno IV Dedicatoria A Dios porque Él es quien da la sabiduría y de su boca viene el conocimiento y la inteligencia. A mis padres y hermana por brindarme su apoyo y ayuda durante mi carrera. A mis tíos y abuelos por enseñarme que el trabajo duro trae sus recompensas y que no es imposible alcanzar las metas soñadas, sino que solo es cuestión de perseverancia, trabajo, esfuerzo y tiempo. A mis amigos: Ana, Adriel, Miguel, Angélica, Deisy, Jonathan, Antonio, Daniel, Irving, Lupita, Christian y quienes me falte nombrar, pero que se han convertido en verdaderos compañeros de vida. v Agradecimientos Agradezco a Dios por haberme permitido llegar hasta este punto en la vida, sin Él, yo nada sería y es Él quien merece el primer lugar en esta lista. Gracias Señor porque tu mejor que nadie sabes cuánto me costó, cuanto espere, cuanto esfuerzo y trabajo invertí en todos estos años, gracias. -

HD PVR 2 Record High Definition Video to Your PC Enregistrez La Vidéo Haute Définition Sur Votre PC

HD PVR 2 Record High Definition video to your PC Enregistrez la vidéo Haute Définition sur votre PC WinTV-DCR-2650 a dual tuner CableCARD receiver for your Windows 7 PC! Record your PC gaming action in true HD. Technical specifications/Spécifications technique Share your best games with your friends on Hardware encoder: H.264 AVCHD high definition video encoder, video encode to YouTube! 1080p30 from HDMI or component video Record TV programs in HD from cable & No delay HDMI pass through: satellite boxes. Includes an IR blaster to control HDMI or Component in to HDMI out, up to 1080p Recording datarate: channel changing on your set top box from 1 to 13.5 Mbits/sec Enregistrez vos actions de jeu PC en HD Recording formats: MP4 or TS réel. Partagez vos meilleurs moments Video down conversion Input/output connections avec vos amis sur YouTube! HDMI in from HDMI sources without HDCP (Xbox 360 or PC game Enregistrez les programmes TV en HD de console) votre décodeur câble et satellite. Inclus Component video in, with stereo audio un émetteur infrarouge pour contrôler le S/PDIF optical audio in changement de chaîne sur votre décodeur IR blaster out to control channel changing on a set top box S-Video and composite video in, with stereo audio (requires an optional cable) Bundled software applications/Logiciels inclus HDMI output ArcSoft ShowBiz, with these features: Size: 6 in wide x 6 in deep x 1.5 in high Video capture for recording HD video Weight: .75lb / .34 kg / 12 oz Trim and combine your videos Upload videos to YouTube Burn Blu-ray compatible -

Analog and Digital TV Receivers for Your PC Or Laptop!

Product list www.hauppauge.com PCI PCI Express ExpressCard 54 USB 2.0 Ethernet RJ45 Wi-Fi Number of tuners Number of simultaneous TV channels Analog cable TV digital TV ATSC M/H mobile digital TV ATSC QAM digital TV hardware MPEG-2 encoder HardPVR: Built-in MPEG-2 transport stream recorder SoftPVR: MPEG-2 nition H.264 hardware encoder Hi-defi Windows 7 / Vista compatible Windows XP compatible Remote control included antenna included ATSC Video Additional Interface type TV receiver formats recorder information MediaMVP-HD HD PVR New! Colossus USB-Live2 New! WinTV-Aero-m 1 1 WinTV-HVR-850 1 1 WinTV-HVR-950Q 1 1 WinTV-HVR-1150 1 1 WinTV-HVR-1250 1 1 WinTV-HVR-1500 1 1 WinTV-HVR-1600 2 1 WinTV-HVR-1850 2 1 M WinTV-HVR-1950 1 1 WinTV-HVR-2250 2 2 M PCTV TV tuners New! Broadway 1 1 HD stick 1 1 HD Pro stick 1 1 HD Mini stick 1 1 HD card 1 1 M = Windows Media Center remote control included (some models) Hauppauge Computer Works, Inc. 91 Cabot Court, Hauppauge, NY 11788, USA tel: 631.434.1600 · email: [email protected] www.hauppauge.com Trademarks: Hauppauge logo, SoftPVR, HardPVR and WinTV: Hauppauge Computer Works, Inc. Windows, Vista, Windows XP Media Center Edition: Microsoft Corporation. DivX is a trademark of DivX Networks Inc. All rights reserved. All other trade names are the service mark, trademark or registered trademark of their respective holders. ©2010 Hauppauge Computer Works, Inc. PACK-PKTGUIDE-V2.5-ENG 12/10 Analog and digital TV receivers for your PC or laptop! H.264 digital HD video recorders Internal HDTV TV tuners for your PC External HDTV TV tuners for your laptop or desktop PC Record HD from game consoles or satellite and cable TV set All internal WinTV-HVR boards support analog cable TV, high The external WinTV-HVR’s are designed to plug into USB ports on laptop or desktop PCs. -

Al-Jazeera Through Today

“The opinion, and the other opinion” Sustaining a Free Press in the Middle East Kahlil Byrd and Theresse Kawarabayashi MIT’s Media in Transition 3 May 2-4, 2003 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION......................................................................................................... 2 BACKGROUND AND HISTORY .............................................................................. 3 The Emir and Qatar, ................................................................................................... 3 Al-Jazeera Through Today ......................................................................................... 5 Critics of Al-Jazeera ................................................................................................... 6 BUSINESS MODEL ..................................................................................................... 7 Value Proposition....................................................................................................... 7 Market Segment.......................................................................................................... 8 Cost Structure and Profit Potential............................................................................ 9 Competitive Strategy ................................................................................................ 11 THE GLOBALIZATION OF AL-JAZEERA.......................................................... 13 CHALLENGES AL-JAZEERA FACES IN SUSTAINING ITS SUCCESS ........ 15 AL-JAZEERA’S NEXT MOVES............................................................................. -

Television and the Cold War in the German Democratic Republic

0/-*/&4637&: *ODPMMBCPSBUJPOXJUI6OHMVFJU XFIBWFTFUVQBTVSWFZ POMZUFORVFTUJPOT UP MFBSONPSFBCPVUIPXPQFOBDDFTTFCPPLTBSFEJTDPWFSFEBOEVTFE 8FSFBMMZWBMVFZPVSQBSUJDJQBUJPOQMFBTFUBLFQBSU $-*$,)&3& "OFMFDUSPOJDWFSTJPOPGUIJTCPPLJTGSFFMZBWBJMBCMF UIBOLTUP UIFTVQQPSUPGMJCSBSJFTXPSLJOHXJUI,OPXMFEHF6OMBUDIFE ,6JTBDPMMBCPSBUJWFJOJUJBUJWFEFTJHOFEUPNBLFIJHIRVBMJUZ CPPLT0QFO"DDFTTGPSUIFQVCMJDHPPE Revised Pages Envisioning Socialism Revised Pages Revised Pages Envisioning Socialism Television and the Cold War in the German Democratic Republic Heather L. Gumbert The University of Michigan Press Ann Arbor Revised Pages Copyright © by Heather L. Gumbert 2014 All rights reserved This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (be- yond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher. Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America c Printed on acid- free paper 2017 2016 2015 2014 5 4 3 2 A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 978– 0- 472– 11919– 6 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978– 0- 472– 12002– 4 (e- book) Revised Pages For my parents Revised Pages Revised Pages Contents Acknowledgments ix Abbreviations xi Introduction 1 1 Cold War Signals: Television Technology in the GDR 14 2 Inventing Television Programming in the GDR 36 3 The Revolution Wasn’t Televised: Political Discipline Confronts Live Television in 1956 60 4 Mediating the Berlin Wall: Television in August 1961 81 5 Coercion and Consent in Television Broadcasting: The Consequences of August 1961 105 6 Reaching Consensus on Television 135 Conclusion 158 Notes 165 Bibliography 217 Index 231 Revised Pages Revised Pages Acknowledgments This work is the product of more years than I would like to admit. -

The Technology of Television

TheThe TechnologyTechnology ofof TelevisionTelevision Highlights, Timeline, and Where to Find More Information Summer 2003 THE FCC: SEVENTY-SIX TV TIMELINE YEARS OF WATCHING TV Paul Nipkow shows 1884 how to send From the Federal Radio images over wires. Commission’s issuance of the first television Campbell Swinton and 1907 license in 1928 to Boris Rosing suggest today’s transition using cathode ray tubes to digital tv, the to transmit images. Federal Vladimir Zworkin 1923 patents his iconscope - the camera tube many call the cornerstone of Communications modern tv—based on Swinton’s idea. Commission has been an integral player in the Charles Jenkins in the 1925 technology of television. U.S. and John Baird in England demonstrate the mechanical trans- One of the fundamental mission of pictures over wire circuits. technology standards that the FCC issued in Bell Telephone and the 1927 May 1941, which still Commerce Department stands today, is the conduct the 1st long NTSC standard for distance demonstration programming to be 525 of tv between New York and Washington, DC. lines per frame, 30 frames per second. Philo Farnsworth files 1927 a patent for the 1st complete electronic When this standard was and hue of red, green, and television system. first affirmed it was called Today the FCC continues to blue on the color chart. The Federal Radio 1928 “high-definition television” play a key role in defining the technology standards that must Commission issues the because it replaced 1st tv license (W3XK) be met as the United States programming being broadcast to Charles Jenkins. at 343 lines or less. -

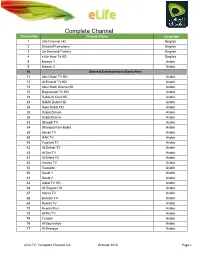

Complete Channel List October 2015 Page 1

Complete Channel Channel No. List Channel Name Language 1 Info Channel HD English 2 Etisalat Promotions English 3 On Demand Trailers English 4 eLife How-To HD English 8 Mosaic 1 Arabic 9 Mosaic 2 Arabic 10 General Entertainment Starts Here 11 Abu Dhabi TV HD Arabic 12 Al Emarat TV HD Arabic 13 Abu Dhabi Drama HD Arabic 15 Baynounah TV HD Arabic 22 Dubai Al Oula HD Arabic 23 SAMA Dubai HD Arabic 24 Noor Dubai HD Arabic 25 Dubai Zaman Arabic 26 Dubai Drama Arabic 33 Sharjah TV Arabic 34 Sharqiya from Kalba Arabic 38 Ajman TV Arabic 39 RAK TV Arabic 40 Fujairah TV Arabic 42 Al Dafrah TV Arabic 43 Al Dar TV Arabic 51 Al Waha TV Arabic 52 Hawas TV Arabic 53 Tawazon Arabic 60 Saudi 1 Arabic 61 Saudi 2 Arabic 63 Qatar TV HD Arabic 64 Al Rayyan HD Arabic 67 Oman TV Arabic 68 Bahrain TV Arabic 69 Kuwait TV Arabic 70 Kuwait Plus Arabic 73 Al Rai TV Arabic 74 Funoon Arabic 76 Al Soumariya Arabic 77 Al Sharqiya Arabic eLife TV : Complete Channel List October 2015 Page 1 Complete Channel 79 LBC Sat List Arabic 80 OTV Arabic 81 LDC Arabic 82 Future TV Arabic 83 Tele Liban Arabic 84 MTV Lebanon Arabic 85 NBN Arabic 86 Al Jadeed Arabic 89 Jordan TV Arabic 91 Palestine Arabic 92 Syria TV Arabic 94 Al Masriya Arabic 95 Al Kahera Wal Nass Arabic 96 Al Kahera Wal Nass +2 Arabic 97 ON TV Arabic 98 ON TV Live Arabic 101 CBC Arabic 102 CBC Extra Arabic 103 CBC Drama Arabic 104 Al Hayat Arabic 105 Al Hayat 2 Arabic 106 Al Hayat Musalsalat Arabic 108 Al Nahar TV Arabic 109 Al Nahar TV +2 Arabic 110 Al Nahar Drama Arabic 112 Sada Al Balad Arabic 113 Sada Al Balad